Network operator National Grid yesterday announced plans to balance the UK’s electricity supply and facilitate more renewable energy generation. As part of the move, it intends to pay some companies to use less power at times when demand is high.

That hit headlines, with the new measure variously described as an “emergency plan” to avoid power blackouts and a “safety net” to ensure the kettle always boils. So which is it?

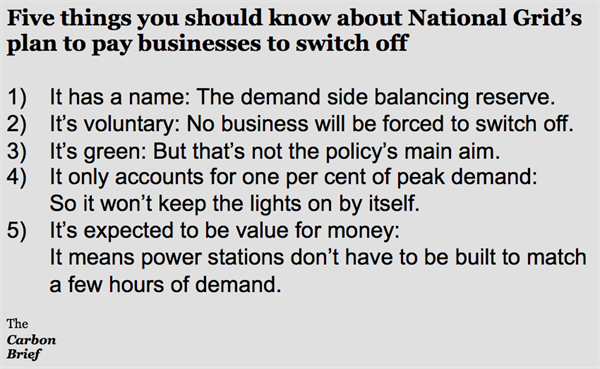

Here’s a guide to the small but significant new policy.

What is it?

The plan has two components. National Grid intends to pilot what it calls a ‘demand side balancing reserve’ this winter, and introduce a ‘supplemental balancing reserve’ next year.

The demand side reserve is the measure that caught the media’s attention. National Grid will pay energy intensive business to reduce their use during peak times – 4pm to 8pm on winter weekdays. Reducing the amount big power users need at peak time should help National Grid match demand for power with supply.

National Grid says the measure should be good value for consumers, as it avoids the need to build additional power stations just to meet sporadic peaks in demand. National Grid stresses that the scheme is voluntary, and no business will be forced to switch off. Many large companies already reduce their energy use in peak times to save money, it notes.

Moreover, the measure covers less than one per cent of peak winter demand. So the new measures are smoothing around the edges, rather than making a big dent in demand.

The supplemental reserve is something quite different. It’s a measure intended to keep power plants that would be mothballed because of a lack of demand open. National Grid will pay energy generators to keep these plants – normally gas – in a state where they can be switched on quickly to meet peak demand.

National Grid already buys some extra power through the short term operating reserve when there’s unexpected shortages, such as when a power plant fails. The supplemental reserve is just an extension of that policy.

Why is it necessary?

The UK is cutting power sector emissions as part of its effort to combat climate change. That means adding lots of renewable power to the grid, which peaks and troughs as the weather conditions change. National Grid’s balancing reserves help match that variable supply with demand.

A couple of EU policies have boosted the UK’s decarbonisation efforts. The EU requires the government to meet 15 per cent of the UK’s energy demand from renewable sources by 2020. That means building a lot more wind and solar farms. Thanks to some pretty major investment in the last decade or so, the UK is currently on track to hit that target.

At the same time, the EU’s Large Combustion Plant Directive and its replacement, the Industrial Emissions Directive, are helping to phase out fossil fuel powered plants with harmful emissions. The policies require power stations to fit new equipment to curb nitrous oxide and sulphur dioxide emissions if they want to keep operating. That means power stations that can be fired up at any time are being shut down and will no longer be available to balance the grid.

So the UK is increasingly relying on a lot of low carbon, variable, power. Consultancy Poyry estimates that by 2020, the main uncertainty around the UK’s electricity supply will be how much wind power is available, not how much demand there will be – as has traditionally been the case.

So National Grid is embracing any measure that can help match supply and demand. Particularly during hours when most people are using power.

Is it a ‘green’ policy?

The new measures should help reduce energy sector emissions, but that’s not National Grid’s principal goal.

The balancing reserves will help highly polluting coal power plants can shut down without National Grid having to worry about running out of power when demand is high. That should also give the government and investors the confidence to keep building renewables.

As the energy secretary Ed Davey says, a major grid failure would “not be a career-enhancing moment”, but these measures should help ensure “the lights will stay on this year, next year and into the future”. The fact it should help the UK decarbonise its energy sector is an added bonus.

Why are some people criticising it?

Some critics see the plans as another example of the UK needed to spend money to support an ideologically-tinged “drive for wind farms”.

Lobby group the Energy Intensive Users Group told Sky News the new measures are the result of the government being “overly focused on costly intermittent renewables like wind and solar, which are inherently incapable of providing secure electricity supplies”.

But the government doesn’t really have much choice about ramping up renewables. Countries can’t continue burning fossil fuels in the same way they have in the past if they want to curb emissions and tackle climate change. Moreover, low carbon alternatives to renewable energy can’t displace fossil fuels on their own. Carbon capture and storage technology is yet to be proven on a commercial power plant. Nuclear is expensive and takes a long time to build.

National Grid’s new measures are part of coping with that reality.