What the IPCC report says about extreme weather events

Freya Roberts

10.11.13The world has already witnessed more hot days and heat waves since the 1950’s – and the new IPCC report warns we’ll see more changes to weather extremes by the end of 21st century. But a close look at the report reveals that rising temperatures won’t affect all kinds of extreme events in the same way.

Here’s a quick run through of what the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says about hot days, heat waves, hurricanes and heavy rain – past and future.

What’s the big deal about extremes?

Extreme events expose humans to conditions beyond the realms of what we’re used to. That could be unusually high temperatures, sudden heavy downpours, or longer lasting droughts. If people and the infrastructure we rely on can’t withstand these abnormal conditions, the economic and human losses can be huge.

Take the 2003 European heatwave. It had devastating human consequences, with tens of thousands of people estimated to have died when temperatures rose above 40 degrees Celsius for a number of weeks. Or look at superstorm Sandy last year: the economic losses are thought to be in region of $50 billion.

With losses like these at stake, planners and policymakers are under pressure to be prepared.

What has been happening?

The science summed up in the new IPCC report shows that since the 1950s there have been clear changes in many types of extreme events. Some of this is new, but some of it was summarised in a special report on extreme events the IPCC published in 2012.

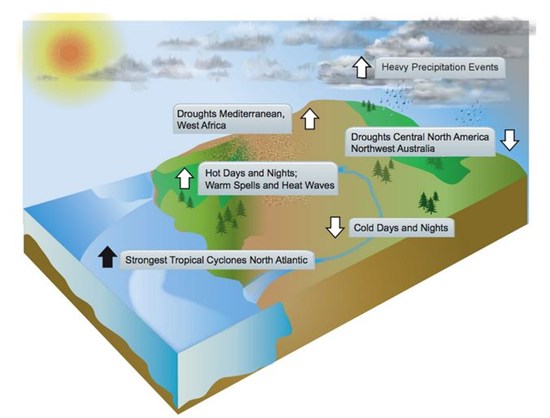

We’ve experienced more hot days and heat waves, fewer cold nights, and an increase in the intensity and number of heavy rainfall events, as an image from Chapter 2 of the report shows:

For many of these changes, a human ‘fingerprint’ or influence can be seen. The new IPCC report states it’s very likely (at least 90 per cent certain) humans contributed to the increase in hot days and decrease in cold days. For heat waves, it’s likely (at least 66 per cent certain) human activities were a contributing factor – scientists can’t be more certain because they don’t have as much data on heatwaves to draw conclusions from.

With other types of extreme events, changes in past trends and any human contribution are harder to spot. Take hurricanes for example – there’s no clear pattern suggesting how they’ve changed the world over. But scientists have identified certain parts of the ocean, like the North Atlantic, where the number of intense hurricanes has increased since the 1970s. Drought trends also differ from region to region, with a global picture unclear.

One extreme missing from this picture is flooding. At the moment scientists don’t have enough data to make conclusive statements about changes in the last few decades, or make predictions about the future.

What lies ahead?

Based on the latest generation of climate models, the IPCC is also able to assess how likely it is that each type of extreme events will become more intense or frequent by the end of the century,

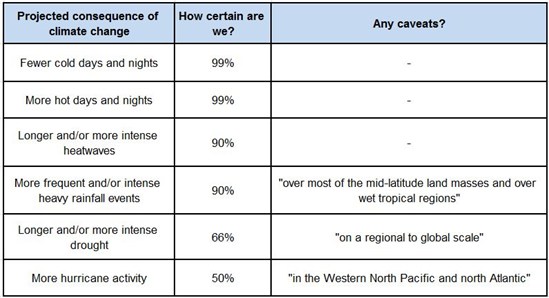

The table below, taken from a section of the report known as the Summary for Policymakers, shows scientists are virtually certain (99 per cent) we’ll experience more hot days and fewer cold days by the end of the 21st century. The report also states it’s very likely (90 per cent certain) there will be longer or more intense heat waves (or both):

Some of the future projections come with caveats. So the report says it’s very likely – or 90 per certain – there will be more heavy rainfall “over most of the mid-latitude land masses and over wet tropical regions”. Mid-latitude land masses include regions like the US and Europe. These wet parts of the world are generally projected by climate models to get wetter, whereas some parts of the world are projected to dry.

Scientists are slightly less certain about changes to drought in the future, as was the case when they looked for changes in past drought trends. It’s still likely (66 per cent certain) droughts will become longer or more intense by the end of the century. In many dry regions, soils are predicted to dry out as temperatures rise and atmospheric circulations of water change.

On hurricanes, climate models predict it is more likely than not – meaning that there is over a 50 per cent chance – that the number of the most intense storms will increase in certain parts of the world. Globally, however, the IPCC says it’s likely the number of tropical cyclones will “either decrease or remain essentially unchanged”. It’s hard to make predictions about these types of storms as the processes involved occur on much smaller scales than climate models can currently replicate.

A useful update for decision-makers

All in all, the IPCC report demonstrates that some types of extreme event will become more severe or intense or long lasting as the world warms. As we’ve noted before, it’s not one size fits all when it comes to extreme events. Scientists are more certain about extremes related to temperature, while finding patterns or predicting changes in small, localised climate extremes like hurricanes is harder to do.

It’s worth noting too that this global outlook approach often masks big regional differences – here’s the Europe case study for example.The next part of the IPCC’s report, due out in March 2014 should provide policymakers with more information about the impacts of these changes on more regional scales.

But this sort of overview is useful in helping planners to prepare for an increase in a number of potentially very costly threats. Past events have already demonstrated the risks of not being prepared for these events when they strike.

Updated 15/10/13 - A quote from Chapter 14 of the IPCC report has been added to reflect that the number of hurricanes globally are projected to decrease or remain unchanged.