US trying harder on climate change than ‘unambitious’ China, says study

Sophie Yeo

12.20.16Sophie Yeo

20.12.2016 | 1:07pmThe US is working harder to reduce its emissions than China, according to research published in Nature Climate Change, while India is making more effort than both.

The controversial findings, which rely on a number of definitions for “equity”, are based on the climate pledges that countries submitted to the UN as part of the Paris climate deal, known as “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs).

Each country has to say why their pledge is “fair and ambitious”, but there has so far been no formal way to assess these claims. Scientists have now developed a method to determine how equitable each pledge really is.

Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement, which came into force in November this year, sets the goal of limiting global temperature rise to well below 2C, and to 1.5C if possible.

This is supposed to be achieved equitably, recognising that some countries have more capacity to act, and that some bear more responsibility for the problem.

Each country decides how far it will address its own emissions. While this light-touch approach got everyone on board with the agreement, it means that some states can commit to doing less than others.

Current NDCs will result in more than 2C warming, according to the paper. To hit this goal, emissions in 2030 would have to be cut to 39.7 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e) per year, down from projected levels of 52.5GtCO2e per year, it says. As a result, climate ambition has to increase over the next decade. A key question is how to do so equitably.

Countries have already agreed to improve their NDCs every five years, via a process known as the “ratchet mechanism“. These progress assessments should happen “in light of equity and the best available science”, according to the agreement, then become more ambitious over time.

But “equity” means different things to different people. There have been debates for years about how to calculate, calibrate and assess pledges based on equity.

In the absence of a formal definition, this new paper looks at different ways to define equity, how countries are measuring up according to the various definitions, and how to fairly increase ambition in the coming years to meet the Paris goals.

Defining equity

The scientists have worked with five definitions of equity, originally set out by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the UN’s climate science body.

The first allocates emissions based upon capability, where rich countries have to make more effort. The paper labels this “capability” (CAP). The second is based upon equality, where per person emissions eventually converge so that everyone emits the same (“equal per capita”, or EPC).

The third combines responsibility, capability and need, so that wealthy countries that have emitted the most historically have to make the most effort (“greenhouse development rights, or GDR). The fourth is based solely upon historical responsibility (“equal cumulative per capita”, or CPC), so that countries that have emitted the most in the past will bear most of the burden in the future.

The fifth maintains current emissions ratios (“constant emissions ratio”, or CER), so that each country continues to emit the same share of global emissions as it does at the moment, even as the total volume is cranked down.

The study acknowledges that the fifth option is not an approach currently advocated by any countries, although it suggests that it is “implicitly” championed by developed countries that stress national circumstances as an impediment to cutting emissions.

“Philosophers argue against [CER],” lead author Yann Robiou du Pont, from the University of Melbourne, tells Carbon Brief.

Sivan Kartha, an expert in equity at the Stockholm Environment Institute who was not involved in the study, says the prominence given to CER (also known as “grandfathering“) in the paper is problematic. He tells Carbon Brief:

“It over-emphasizes ‘grandfathering, which privileges those who are currently high-emitters, and penalizes those whose emissions are currently low. Generally, grandfathering wouldn’t be considered an “equity approach”, but rather some sort of concession to politically powerful players.”

The scientists allocated a fair slice of the total volume of emissions to each country for each equity scenario, for both the 2C and 1.5C goals. They compared this allocation to what it had actually promised in its NDC.

Both temperature goals could be achieved in a number of different ways, depending on the emissions peaking date and the steepness of the reductions thereafter. The paper, and the graphs below, consider both the average and the range of these possible paths towards the goal.

Which NDCs are equitable?

This approach shows that, while the world is collectively missing its Paris Agreement goal, there are some countries that are already doing their fair share, according to some definitions, while others are lagging behind. Robiou du Pont tells Carbon Brief:

“Any country within the range of an equity approach (for either below 2C or 1.5C) is doing its fair share based on that approach. This means that if all countries followed the same equity approach, the world would be on track, for either below 2C or 1.5C.”

The findings are reported in the paper, but also in a corresponding website, Paris Equity Check, which provides more detail on each country. The graphs below are taken from the website, rather than the paper.

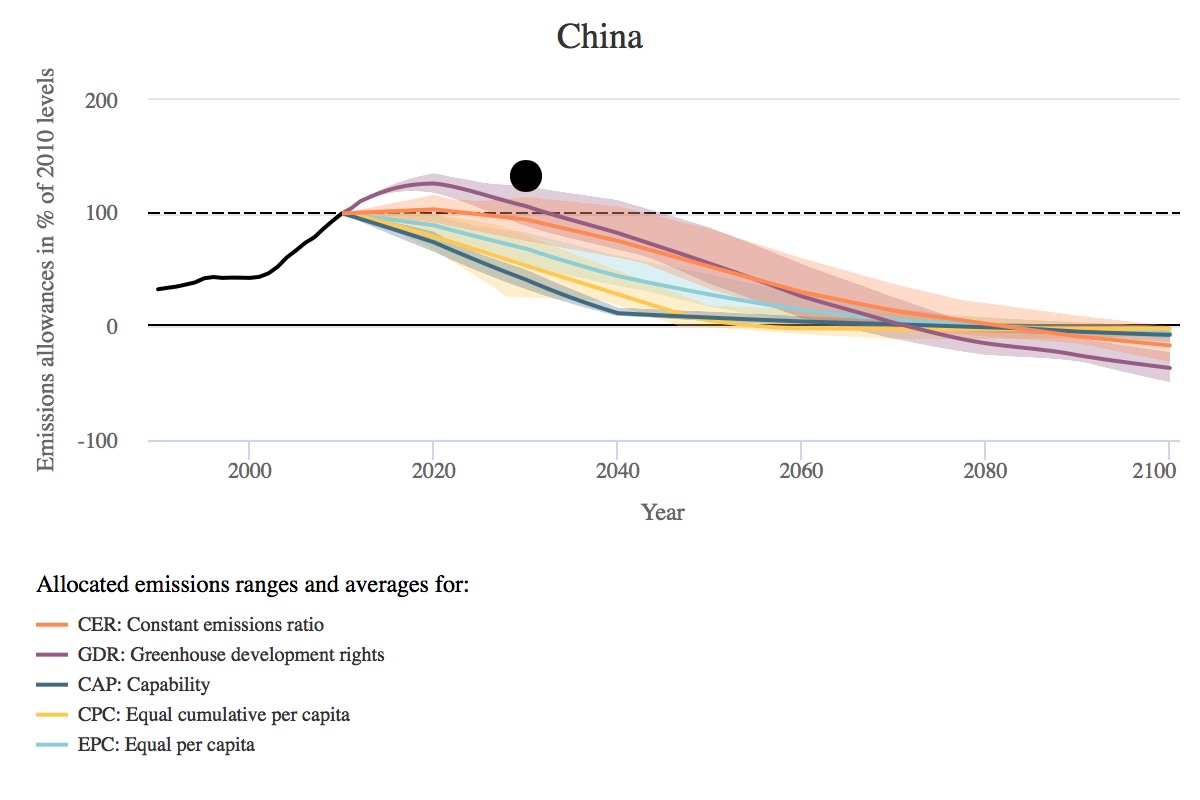

China comes out of the analysis badly. Under all five of the equity approaches, it needs to peak its emissions at an earlier date and at a lower level than it has promised in its NDC.

Averaged over all five of the equity approaches, China needs to reduce its emissions by 27% by 2030 compared to 2010 levels in order to hit the 2C goal, and by 48% for 1.5C, peaking its emissions immediately in both cases. So far, it has pledged to peak “around 2030”.

However, one factor to keep in mind is the likelihood of the country actually achieving its NDC. Robiou du Pont tells Carbon Brief:

“China’s NDC is unambitious any way we look at it in our assessment. However, China is very likely to overachieve or increase its NDC, so the ultimate ambition of China may not be so low. We are only assessing its NDC. Other countries may take more ambitious NDCs without the certainty to deliver them. Germany is, perhaps, in that situation.”

China’s NDC compared to its “fair share” according to five equity approaches for a 2C scenario. The solid lines show the average for the scenario, and the blocks of colour show the range. The black dot shows the NDC pledge, and black line shows emissions to date. Source: Paris Equity Check (website associated with Nature Climate Change paper).

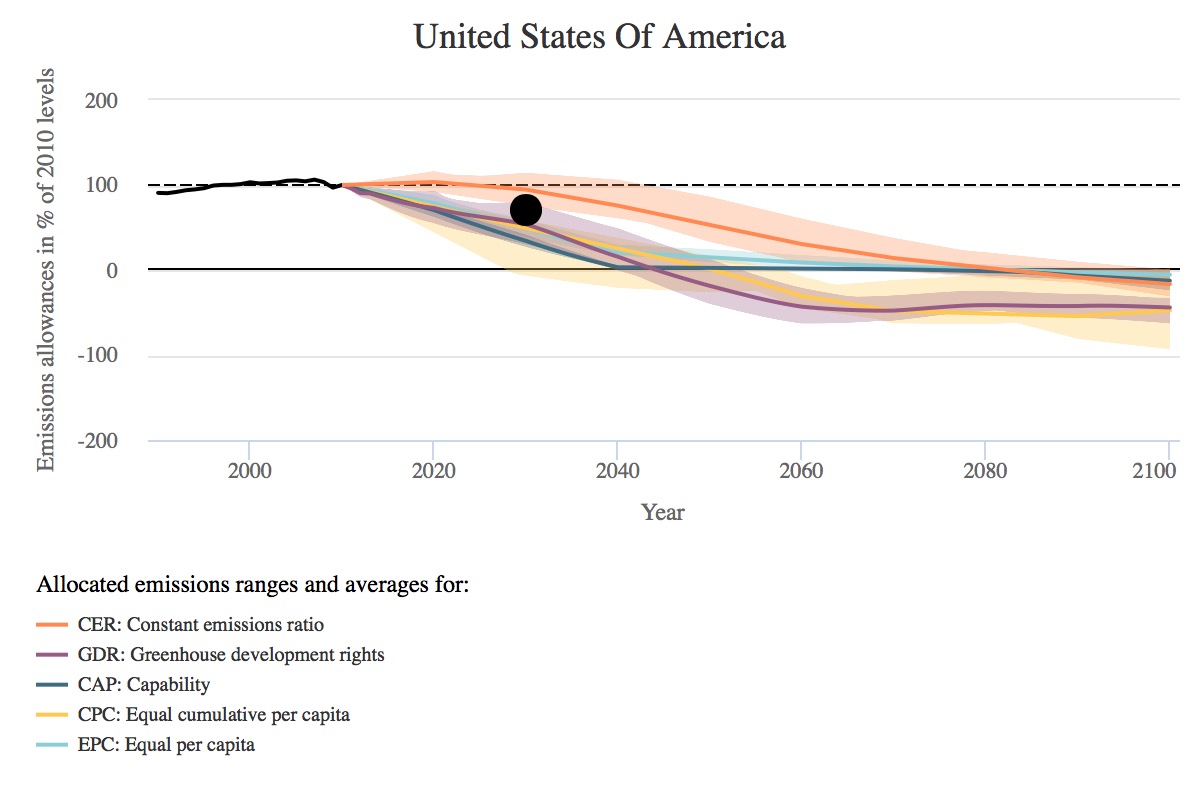

The US fares better than China, although only slightly. It meets the CER scenario easily, although it is worth noting that this is the equity scenario that has been largely dismissed as a “fair” approach to tackling climate change. It also falls within the range of one other equity scenario.

(The paper incorrectly states that it falls into two other scenarios, although the website has the correct data. Carbon Brief identified the mistake and a correction should be forthcoming, according to the authors. Crucially, this means that the US NDC is not more ambitious than India, as the paper claims.)

However, it is worth noting that an NDC that falls within the fair range, but above the average point, is not actually doing its fair share in the majority of cases, with a high chance the world would still surpass the 2C goal even if everyone else followed the same approach. Robiou du Pont explains:

“Choosing the average of these scenarios…to declare that a country is consistent with an equity approach puts the bar a bit higher than simply being in the range.”

The US’s NDC compared to its “fair share”, according to five equity approaches for a 2C scenario. The solid lines show the average for the scenario, and the blocks of colour show the range. The black dot shows the NDC pledge, and black line shows emissions to date. Source: Paris Equity Check.

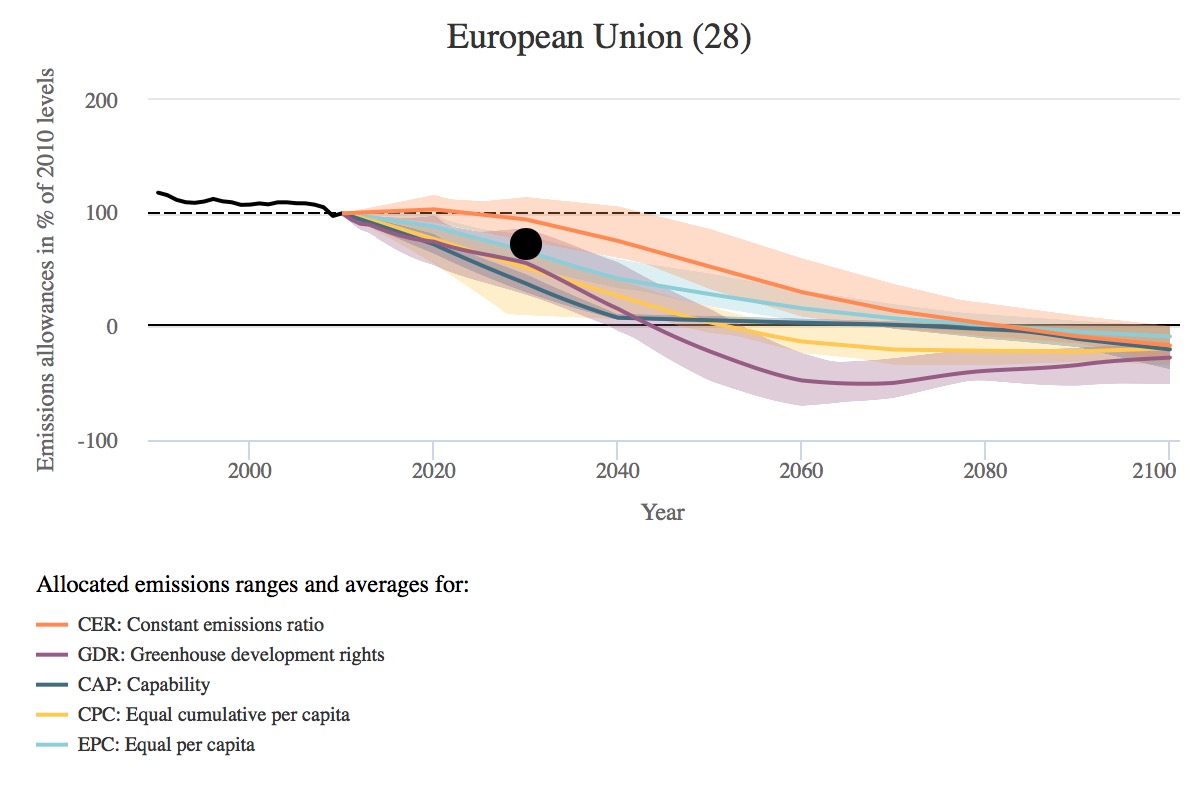

Similarly, the EU’s NDC is not considered fair under the majority of scenarios, only really meeting the CER approach. Like the US, it does fall into the ranges of some of the other approaches.

The EU’s NDC compared to its “fair share” according to five equity approaches for a 2C scenario. The solid lines show the average for the scenario, and the blocks of colour show the range. The black dot shows the NDC pledge, and black line shows emissions to date. Source: Paris Equity Check.

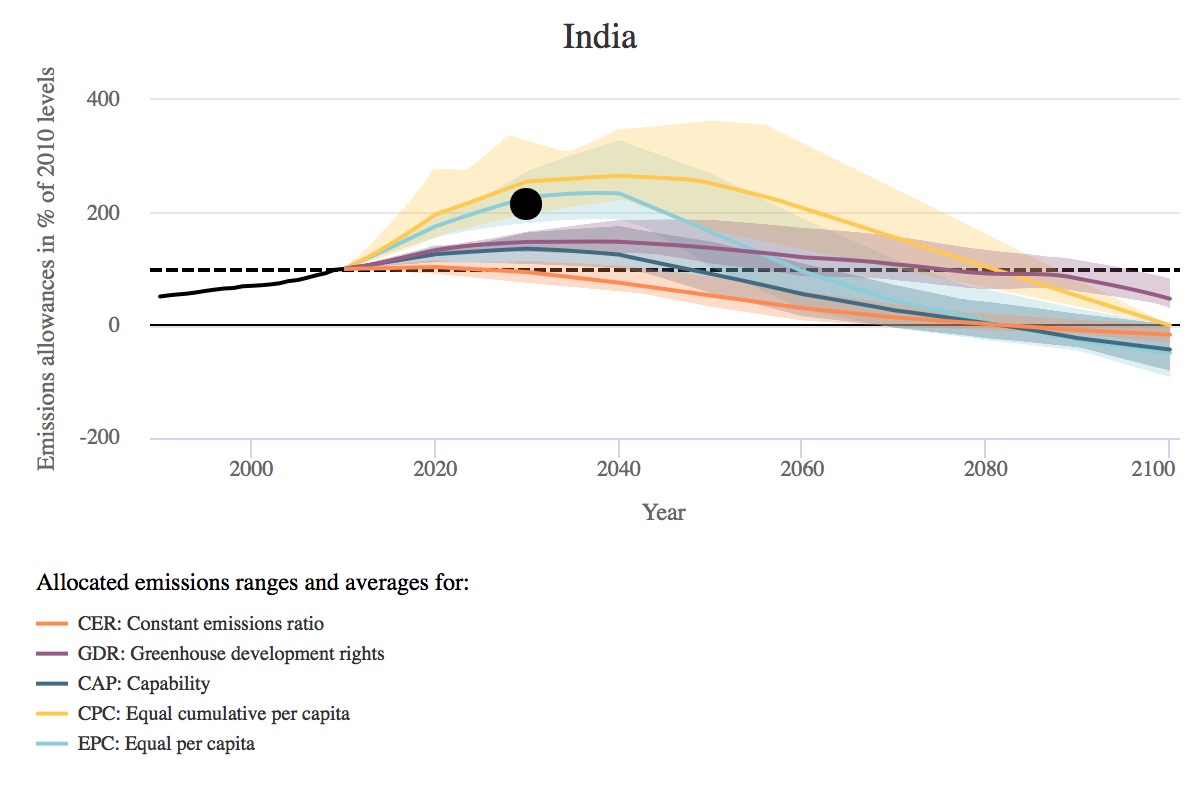

India’s NDC, on the other hand, can be considered fair, according to the two equity approaches which assign the most mitigation effort to countries with high historical emissions.

India’s NDC compared to its “fair share” according to five equity approaches for a 2C scenario. The solid lines show the average for the scenario, and the blocks of colour show the range. The black dot shows the NDC pledge, and black line shows emissions to date. Source: Paris Equity Check.

The situation changes when the Paris goal is tightened to 1.5C, with far fewer countries offering an equitable effort towards hitting the temperature goal.

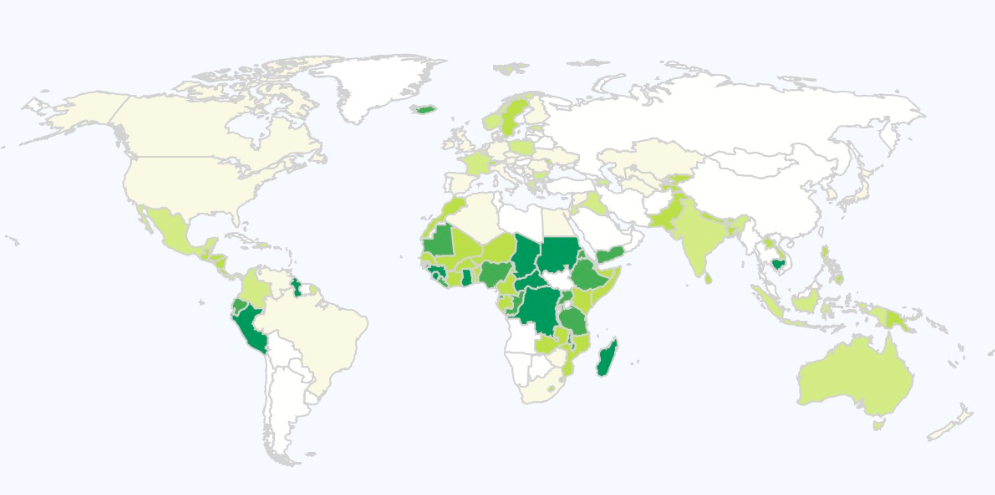

Global ambition for a 2C scenario. Darker shades of green indicates that the country’s NDC can be considered equitable under more definitions of equity. Source: Paris Equity Check.

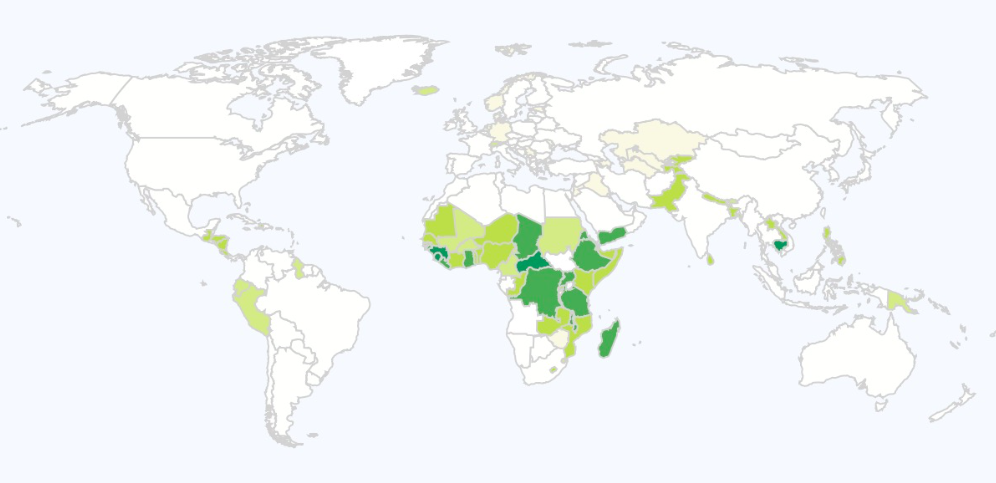

Global ambition for a 1.5C scenario. Fewer countries are offering NDCs than can be considered equitable. Source: Paris Equity Check.

Measuring equity

Judging a nation’s NDC based upon how many definitions of equity it satisfies could represent a “political compromise”, according to the paper.

“More countries in line with many equity approaches would bring the world closer to achieving the Paris Agreement goals, and the country’s pledges would de facto be considered ambitious by more observers,” says Robiou du Pont.

However, he adds that it is also a necessarily flawed way of judging the NDCs. Each country is likely to perceive its own interpretation of equity as the right one, and see other definitions as unfair. “Mixing multiple visions of equity is not equitable for anyone considering equity to be universal,” he says.

In the individual examples above, for instance, national NDCs adhere to the definition of equity that allow them to emit the most. Deeming the US NDC “fair” because it meets the CER definition of equity would be to ignore the fact that no country, including the US, has actually suggested this could be a fair approach. Robiou du Pont says:

“In the case of the US and EU, they are doing their fair share only following some of the equity concepts, India according to some others, and China according to none. I wouldn’t say that any of these are doing their fair share overall, or in absolute terms.”