Should you worry that fracking will cause earthquakes? The short answer is: probably not.

But as more studies are conducted, researchers are developing their understanding of how the fracking process interacts with seismic activity.

Last year, a widely-cited study concluded that compared to other kinds of mining, fracking usually only causes minor tremors. But two papers in the past twelve months suggest the processes associated with fracking could increase the likelihood of small tremors.

We take a look at the evidence.

Fracking and earthquakes

Hydraulic fracturing – known as fracking – involves pumping a fluid made of water mixed with chemicals at high pressure into a drilled well. The fluid creates fractures in the rock, making it possible to extract oil or gas trapped there. So fracking essentially causes minor earthquakes by design, as cracking the rock causes tremors.

But research shows fracking very rarely causes earthquakes people can actually feel. The US Geological Survey found the number of small earthquakes in the USA increased significantly as the fracking industry was developed there. But the vast majority of those earthquakes were “micro” earthquakes registering less than 1 on the moment magnitude scale – a modern version of the better known Richter scale.

Shale gas exploration is simply not in the “premier league” of serious earthquake causes, says Professor Richard Davies, director of Durham University’s Energy Research Institute. Its study of 198 locations showed fracking caused much smaller tremors than other mining processes. Davies has said most fracking induced earthquakes release less energy than someone jumping off a ladder onto the floor.

Wastewater earthquakes

The Durham study caught the media’s attention, with a swathe of headlines declaring fracking was not a significant cause of earthquakes. But it is worth pointing out that fracking has been linked to some earthquakes that have been felt, if only in three places: one each in Lancashire, the USA, and Canada.

But while fracking itself may not generally cause the earth to shake in a way humans can feel, new research shows processes associated with oil and gas extraction can. A paper published in the journal Science last year suggests oil and gas extraction processes – both conventional and unconventional – can be associated with more serious earthquakes.

Extracting oil and gas uses a lot of water, which has to be disposed of – often by pumping it back underground. Pumping the wastewater into the rock can stress geological fault lines and lead to mid-sized earthquakes, the study suggests.

The researchers from Columbia University’s Earth Observatory and the University of Oklahoma’s School of Geology and Geophysics found that large earthquakes thousands of miles away could trigger mid-sized earthquakes in US oil and gas fields which were already stressed by wastewater pumping. Lead author of the study, Nicholas van der Elst, says “the fluids are driving the faults to their tipping point”.

The research shows how a huge earthquake in Chile eventually triggered a mid-sized earthquake in Oklahoma in 2011 which destroyed 14 homes and injured two people. That earthquake registered 5.7 on the moment magnitude scale – the largest earthquake ever associated with wastewater injection.

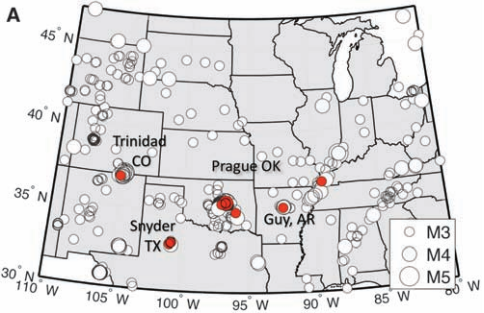

Similarly, earthquakes in Japan and Sumatra set off mid-sized tremors around wells in Texas and Colorado, the study shows. The red dots on the map below show where the earthquakes occurred:

The sites share some characteristics: they all have a long history of wastewater injection – over a period of decades – and are located near critically stressed faults in the rock.

So while fracking itself may not cause the earth to perceptibly shake, pumping wastewater from the associated processes in certain areas means “a larger induced earthquake could be possible or even likely”, the study says.

A new paper seems just published in the journal Science to support this view. It shows that when larger than usual amounts of wastewater are pumped into wells on faultlines, earthquakes can occur.

A team of researchers from three US universities created a model to establish how the buildup of pressure from wastewater wells could spread out. Their research suggests four wells could be responsible for a fifth of Oklahoma’s earthquakes.

Each of the wells was pumped with around four million barrels of water a month, the BBC reports – considerably more than the thousands of other wells in the area. At the same time, the state has seen a rapid rise in the rate of magnitude three or higher earthquakes in the past twelve months.

The researchers’ model suggests that filling the wells to such an extent was “potentially responsible” for the region’s series of small earthquakes – known as a “swarm”.

So while the tremors are still relatively weak, the increase in seismic activity and its correlation with the fracking industry’s wastewater disposal could be significant.

Knowing when to stop

Knowing this could actually be helpful. Measuring the size and frequency of the earthquakes could tell drillers when it’s getting dangerous to continue.

One of the authors of last year’s paper, Heather Savage, says:

“If the small number of earthquakes increases, it could indicate that faults are becoming critically stressed and might soon host a larger earthquake”.

The studies underlines the importance of monitoring earthquake activity. As fracking becomes more widespread, there will be more wastewater disposal and more faults to stress. If the UK is determined to start fracking, this research may be the key to knowing when it’s time to stop.