Mat Hope

11.09.2014 | 5:25pmThe world’s climate adaptation efforts have a funding problem. But UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon hopes that situation is about to change.

He’s invited world leaders to a climate summit in New York in two week’s time, where countries are expected to indicate how much they’ll give to the UN’s Green Climate Fund.

The fund was set up in 2009 to help poorer countries insulate themselves from the worst impacts of climate change. The initiative relies on the world’s developed economies pledging cash. After an initial flurry of donations, the fund is starting to run dry.

Pledges

Countries created the Green Climate Fund at the Copenhagen summit five years ago. The agreement was hailed as one the few successes of the otherwise disappointing summit.

The fund is politically important, as it offers developed countries a chance to back up their promise to help poorer countries with hard cash.

Countries promised that by 2020 they’d collectively be giving $100 billion to the fund each year. It’s never been clear how much countries were expected to donate between now and 2020, however.

Nonetheless, there was plenty of early activity. 24 of the world’s richest nations pledged over $30 billion to get the fund going between 2010 and 2012, as part of the UN’s ‘fast start finance initiative’. The UK gave $2.4 billion, the US $7.5 billion, and Germany and France $1.6 billion each. Japan pledged a seemingly huge $15 billion.

Observers cast doubt over how much of this was new money, however, warning that many countries were simply reclassifying funds from their aid budgets as climate finance.

Since 2012, pledges have almost completely dried up. At the end of March 2014, the fund had received a total of $37 million according to its official accounts.

The fund’s executive director Hela Cheikhrouhou said last year that she wants to raise $15 billion by the end of this year. Today, that goal was lowered to $10 billion.

Filling the void

Countries officially have until November to make their pledges, but some are planning on announcing them at the secretary general’s summit in a fortnight’s time.

A few countries have already put their cards on the table. The relatively small sums offered so far could have encouraged the fund’s officials to lower their demands just days more pledges were expected.

Germany was the first developed country to make a pledge since 2010. In July, Angela Merkel’s government promised to give $1 billion spread over two years to the fund.

South Korea has pledged $40 million, driven by the fact that it will be hosting the fund.

A few other countries have also pledged small amounts. Indonesia, another developing country, pledged $250,000. Sweden originally pledged $45 million by the end of 2014, but has ended up splitting the contribution over two years.

France has said it will contribute to the fund, with NGO’s expecting Paris to match Germany’s $1 billion contribution. The UK has promised it’s ready to give to the fund, but has given no indication of how large its contribution will be.

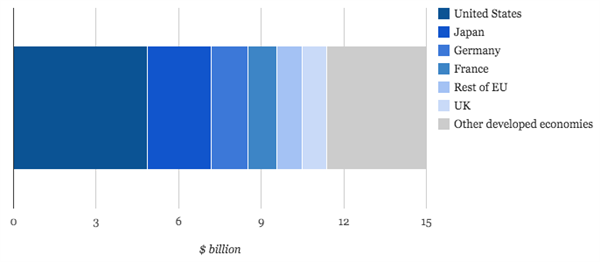

Oxfam has previously suggested how much each country should contribute towards the original $15 billion goal. It based its estimates on the size and health of each country’s economy. The bar below is separated according to Oxfam’s suggested pledges:

Source: Data from Oxfam, graph by Carbon Brief.

Unsurprisingly, Oxfam suggests the US gives the most – a little under $5 billion. France, Germany and the UK should account for around $1 billion each, with Canada contributing $600 million and Australia a bit over $400 million to the fund, Oxfam says.

It seems unlikely the pledges will break down exactly as Oxfam describes, however.

Canada and Australia have both gone very cool on the idea of an international climate deal, so they’re perhaps unlikely to support a scheme helping others cope with the impacts of rising temperatures. Their conservative governments also probably won’t be keen on anything that involves stumping up money.

US negotiators have so far been reluctant to donate due to concerns over who controls the fund.

Hammering out the details of how the fund is structured will no doubt form part of the discussions in New York in a fortnight’s time.

Countries aren’t the fund’s only potential sources of income, however. It can also receive contributions from the private sector through a mechanism known as the private sector facility.

Some commentators are concerned this could leave adaptation policies vulnerable to the sometimes erratic behaviour of international markets, however.

From pledges to policies

Getting countries to cough up is only part of the challenge. Converting pledges into programmes can also be difficult – a problem not confined to the issue of climate change.

Only about two thirds of the funds promised to the Green Climate Fund by May last year were actually delivered. Nonetheless, getting governments to formally announce their intentions is a good first step.

Updated 11/09 at 17.55 to reflect that the funding goal had been lowered to $10 billion. Updated 23/09 at 10.35: Japan pledged $15 billion, not $150 billion as was originally stated.