UK election 2024: What the manifestos say on energy and climate change

Molly Lempriere

06.10.24Molly Lempriere

10.06.2024 | 12:40pmOn 4 July, the UK will head to the polls to elect new members of parliament in the general election.

People up and down the country will vote for a local MP in each of the nation’s 650 constituencies, who will then represent them in Westminster.

After the votes are counted, the King will ask the party with the most elected MPs to form a government, which will then lead the country over the next five years.

Climate change, nature and the net-zero transition are expected to play a “central role” in the election, with the environment and climate change the fifth most important issue to voters – after the cost of living, health, the economy in general and immigration and asylum – according to a recent poll from YouGov.

With the exception of climate-sceptic Reform, all major political parties continue to back the UK’s net-zero climate goal. Heading into the election, however, they have talked about the target in very different ways, with the Conservatives focusing on costs and Labour on benefits.

Following 14 years of Conservative government, which included the Covid-19 pandemic, the global energy crisis and Brexit, the polls overwhelmingly suggest that the opposition Labour party will take power in July.

In the interactive grid below, Carbon Brief tracks the commitments made by major political parties in their latest election manifestos. The grid covers a range of issues connected to energy and climate change.

Each entry in the grid represents a direct quote from one or more of these documents. The grid will be updated as each party publishes their manifesto.

Update 10 July: The Labour party won a “landslide” victory in the UK general election, winning 412 out of 650 seats. This was an increase of 214 seats since the last general election in 2019. The Conservatives won 121 seats, their lowest-ever total and down by 252 since the last election. The Liberal Democrats gained 64 seats, with a total of 72, while the Green party secured four seats and the Reform party five. On Friday 5 July, Keir Starmer became prime minister and has subsequently started appointing his cabinet, including Ed Miliband as secretary of state for energy security and net-zero.

Net-zero and climate framing

While the cost-of-living crisis and healthcare are the biggest focus for voters in the run up to the election, climate change and the environment remain important topics.

All of the major parties – apart from Reform – support cutting emissions to zero or net-zero within their manifestos, and include direct policy commitments to reach this.

While both Labour and the Conservatives are sticking with the UK’s existing net-zero by 2050 target, their manifestos describe climate action in very different ways.

Labour notes that “the climate and nature crisis is the greatest long-term global challenge that we face” but says the action it would take in response is a “huge opportunity”.

One of Labour’s five “missions” says it will: “Make Britain a clean energy superpower to cut bills, create jobs and deliver security with cheaper, zero-carbon electricity by 2030.”

In contrast, while the Conservative manifesto says “we are proud of our record and remain committed to delivering net-zero by 2050”, it says it plans for an “affordable and pragmatic transition” that will “cut the cost of tackling climate change”.

Launching the manifesto, prime minister Rishi Sunak attacked “unaffordable eco-zealotry”, continuing the negative framing of climate action that he has been using since announcing delays to a number of policies last year.

(Polling for the Conservative Environment Network found 55% of voters that backed the party in 2019 supported net-zero, with 72% of those switching to Labour citing net-zero.)

Among the smaller parties, the Liberal Democrats are looking to bring the UK’s net-zero target forward to 2045 “at the latest”, Plaid Cymru want Wales to reach net-zero by 2035 and the Green party are eyeing a “transition to a zero-carbon society as soon as possible, and more than a decade ahead of 2050”.

Meanwhile, Reform embraces climate-sceptic talking points and pledges to scrap the net-zero target. It falsely claims this could save the public sector £30bn a year, even though climate-related government spending is only around £8bn per year.

According to analysis from environmental charities Greenpeace UK and Friends of the Earth, Labour’s manifesto plans for climate and nature scored “four times higher” than the Conservative party’s manifesto.

The manifestos were judged against 40 recommendations from the charities, with the Green party scoring 39 out of 40, the Liberal Democrats 32, Labour 21 and the Conservatives just 5.

This was largely due to the Conservatives using “climate and nature as a wedge issue”, they noted, including supporting oil and gas licences and hitting out at “red tape”.

Clean energy

The election follows the global energy crisis triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and decision to restrict gas supplies to Europe, which saw energy bills across the country soar in recent years and put a renewed focus on energy security.

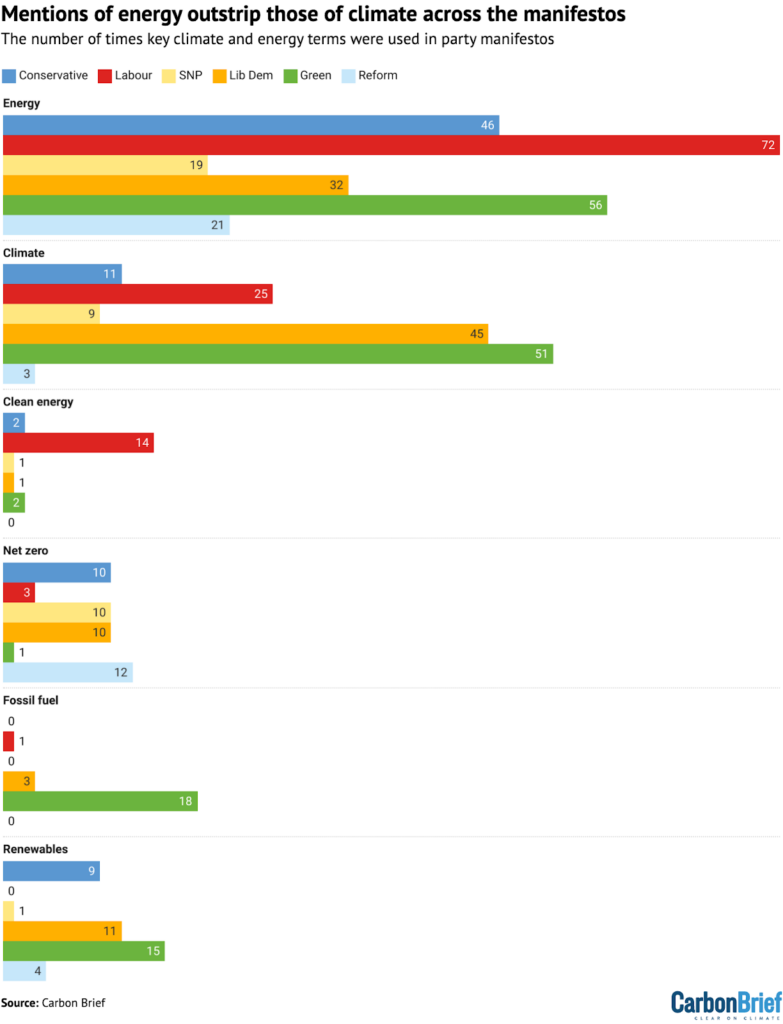

Broadly speaking, and judging on the somewhat simplistic metric of word counts, the manifestos put a greater focus on energy than on climate or net-zero.

For example, the Labour manifesto mentions “energy” 72 times compared with 25 mentions of “climate” and just three of “net-zero”, as shown in the chart below.

While most of the documents refer to renewables, Labour prefers “clean energy”. When it comes to “fossil fuel” and “carbon”, the most frequent mentions come from the Greens.

Notably, the most frequent mentions of “net-zero” come in the Reform manifesto, which makes a series of false or misleading statements on the subject.

One of Labour’s headline policies is Great British Energy, a publicly owned company that it says will invest in new technologies such as floating offshore wind, as well as partnering with local authorities and the private sector to accelerate deployment of mature solutions.

The party is pledging to double onshore wind capacity, treble solar and quadruple offshore wind, as part of its target for clean power by 2030.

It also pledges to “maintain a strategic reserve of gas power stations” , as well as developing nuclear, carbon capture and storage (CCS), hydrogen, marine energy and long-term energy storage.

The Conservative manifesto pledges to treble offshore wind capacity by 2030. It pledges to ensure democratic consent for onshore wind and support solar “in the right place”, including avoiding clusters of solar farms. It does not mention the current government target of clean power by 2035.

It also pledges to support two new fleets of small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs), deliver a large new nuclear power plant at Wylfa in North Wales, new gas power capacity and CCS clusters.

Plaid Cymru also pledges to establish a national energy company within its manifesto, Ynni Cymru, which will expand community owned renewable energy generation across Wales.

The Liberal Democrats are targeting 90% renewable power by 2030.

The Green party wants wind to power 70% of the UK’s electricity by 2030. This would include delivering 80GW of offshore wind, 53GW of onshore wind, and 100GW of solar by 2035.

The SNP expresses support for renewables, but caution about the development of infrastructure such as solar farms and pylons without community support – echoing Plaid Cymru. Additionally, it says it would modernise the “contracts for difference” scheme “to enable the stable deployment of Scotland’s renewable energy pipeline”.

North Sea oil and gas

A key point of debate in the run up to the election has been the future of oil and gas exploration and extraction in the North Sea.

This discussion has been largely unmoored from the fact that the North Sea basin is in inexorable decline. Gas output is set to drop 95% by 2050, even if new licences are issued.

In November, Sunak used the king’s speech to announce legislation for annual oil and gas licensing rounds to “open up clear dividing lines with Labour”, the Guardian reported. The legislation never made the statute book.

The Conservative manifesto reaffirms this commitment to annual licensing rounds “to provide energy to homes and businesses across the country and protect high-skilled and well-paid jobs in the industry”.

(As noted in a factcheck from Carbon Brief last year, the gradual phase-down of high-emitting sectors, such as oil and gas production, is expected to lead to 8,000-75,000 lost jobs, but net-zero is expected to create between 135,000-725,000 net new jobs.)

In contrast, the Labour manifesto says it will not issue any new North Sea licences “because they will not take a penny off bills, cannot make us energy secure, and will only accelerate the worsening climate crisis”. It says it will not revoke licences already issued.

Instead, it says it will “ensure a phased and responsible transition in the North Sea that recognises the proud history of our offshore industry and the brilliance of its workforce, particularly in Scotland and the North East of England, and the ongoing role of oil and gas in our energy mix”.

The SNP manifesto says it will “take an evidence-based approach to oil and gas”, adding that “any further extraction must be consistent with our climate obligations and take due account of energy security considerations”.

The manifesto also champions a “just transition” for oil and gas workers, particularly in Scotland’s north-east, recognising that the North Sea is a declining basin.

Plaid Cymru opposes new licences for oil and gas drilling but does not state a position on existing licences.

The Green party says it would cancel recently-granted licences – such as for the Rosebank field – and pledges to stop all new fossil fuel extraction projects in the UK.

(On 20 June, a landmark decision by the Supreme Court ruled that Surrey County Council should have considered the climate impacts of burning oil from proposed new wells in Horley before granting approval, BBC News reported. The broadcaster said the ruling “could put future UK oil and gas projects in question”.)

Other areas

On homes, both Labour and the Conservatives pledge never to “force people to rip out their boilers” in the transition to lower-carbon heating. The Conservatives pledge to invest £6bn in energy efficiency for 1m homes over the next 3 years, while Labour says it will double planned investment with an extra £6.6bn and a goal to improve 5m homes.

The Liberal Democrats would bring in a 10 year “emergency upgrade” programme offering free insulation and heat pumps for those on low incomes, while the Green manifesto pledges to invest £9bn in low-carbon heating. Reform does not mention home improvements.

On transport, the Conservatives repeat their earlier pledge to invest the £36bn saved from scrapping HS2 in transport, in particular in the North or Midlands. Labour pledges to reinstate the former Conservative policy of banning the sale of new pure combustion-engine cars from 2030, which Sunak pushed back to 2035 late last year.

The Liberal Democrats pledge to rapidly roll out electric vehicle (EV) charging points, reintroducing the plug-in car grant and – like Labour – to restore the requirement that every new car and small van sold from 2030 is zero-emission.

The Green party says it would invest “an additional £19bn over five years to improve public transport, support electrification and create new cycleways and footpaths”.

On forests and nature, the Conservatives will deliver their COP28 commitment to introduce forest risk commodities legislation and deliver on their tree planting and peatland commitments through their “nature for climate” funding. Labour would establish three new national forests in England, plant millions of trees and create new woodlands.

The Liberal Democrats would set binding targets to “stop the decline of our natural environment and ‘double nature’ by 2050”. The Green party plans to introduce a new Rights of Nature Act, “giving rights to nature itself”.