Two degrees: The history of climate change’s speed limit

Carbon Brief Staff

12.08.14Carbon Brief Staff

08.12.2014 | 10:45amLimiting warming to no more than two degrees has become the de facto target for global climate policy. But there are serious questions about whether policymakers can keep temperature rise below the limit, and what happens if they don’t.

As climate negotiators meet in Lima to discuss a new global climate deal that could limit warming to two degrees or less, we look at each of the issues in turn.

Here, we take a look at where the two degree target came from, and how it has ended up guiding international climate policy.

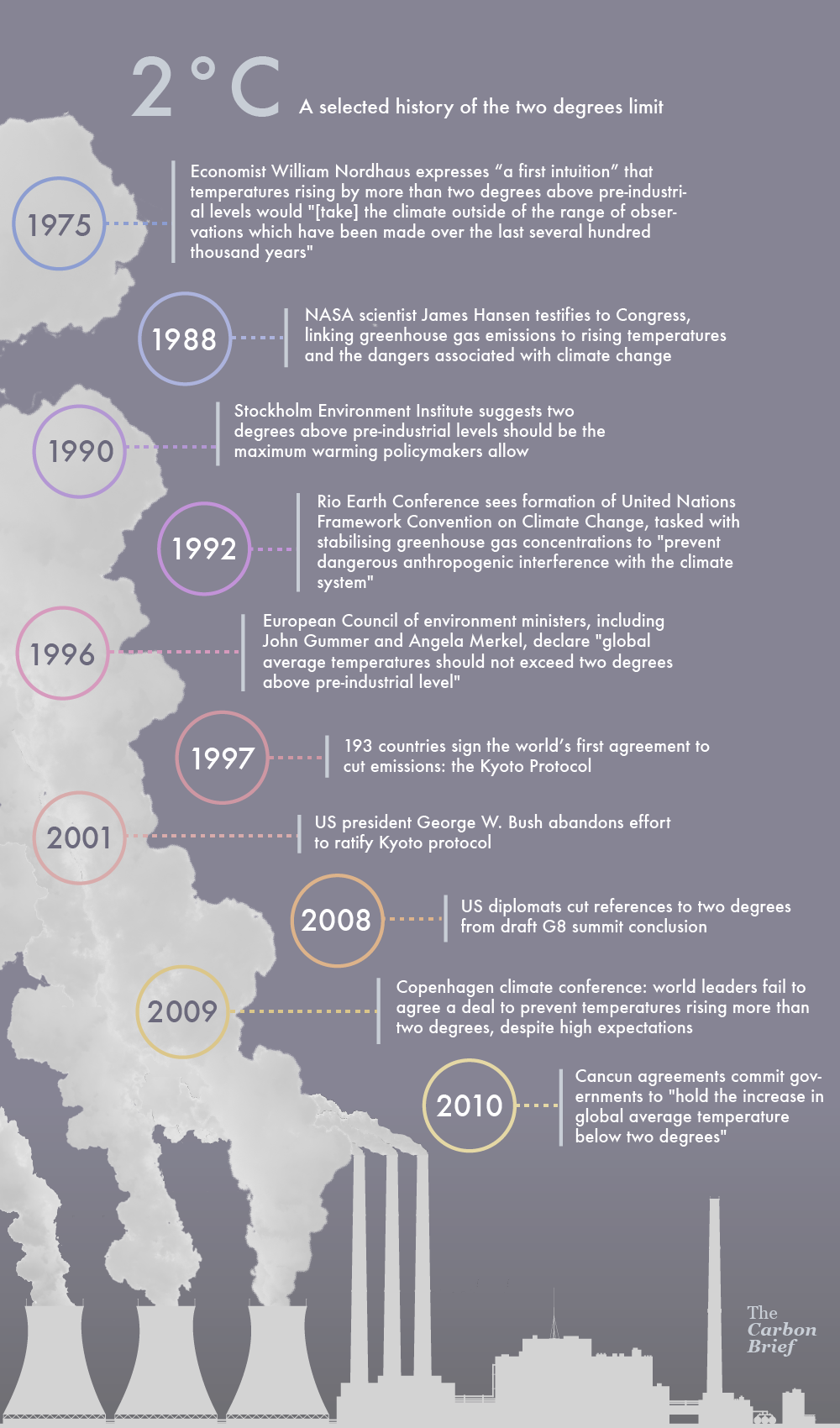

Two degrees: A selected history of climate change’s speed limit. Credit: Rosamund Pearce for Carbon Brief.

A selected history of the two degrees limit. Credit: Rosamund Pearce.

Woven into the fabric of climate policy

Perhaps surprisingly, the idea that temperature could be used to guide society’s response to climate change was first proposed by an economist.

In the 1970s, Yale professor William Nordhaus alluded to the danger of passing a threshold of two degrees in a pair of now famous papers, suggesting that warming of more than two degrees would push the climate beyond the limits humans were familiar with:

“According to most sources the range of variation between between distinct climatic regimes is on the order of around 5°C, and at present time the global climate is at the high end of this range. If there were global temperatures more than 2°C of 3°C above the current average temperature, this would take the climate outside of the range of observations which have been made over the last several hundred thousand years.”

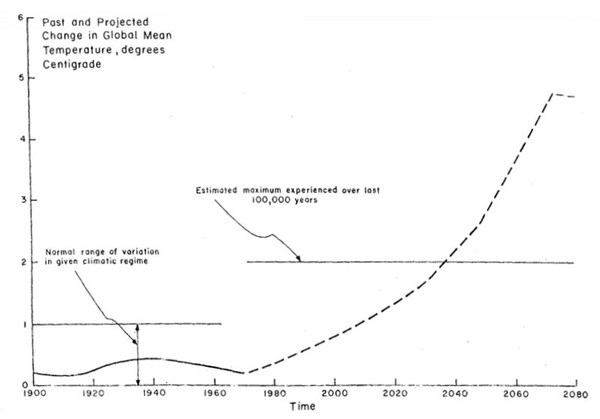

Global mean temperature change projection from Nordhaus’ 1977 paper.

It was a tangential point in the papers. But this, say Carlo and Julia Jaeger from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, who have researched the history of the target, is “perhaps the first suggestion to use two degrees as a critical limit for climate policy.”

More than a decade later, in 1988, NASA professor Jim Hansen gave the issue of climate change a boost, linking greenhouse gas emissions to global warming in a testimony to the US Congress.

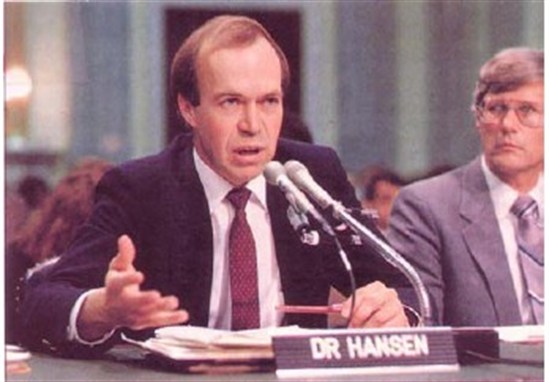

James Hansen presenting early evidence of global warming to the US Congress in 1988. Credit: NASA

Hansen was one of the first scientists to publicly state that rising emissions could have a dangerous impact. His evidence concluded that the earth was warmer in 1988 than ever before, that human-caused emissions were responsible for the warming, and that temperatures were likely to continue to rise, increasing the likelihood of extreme weather events.

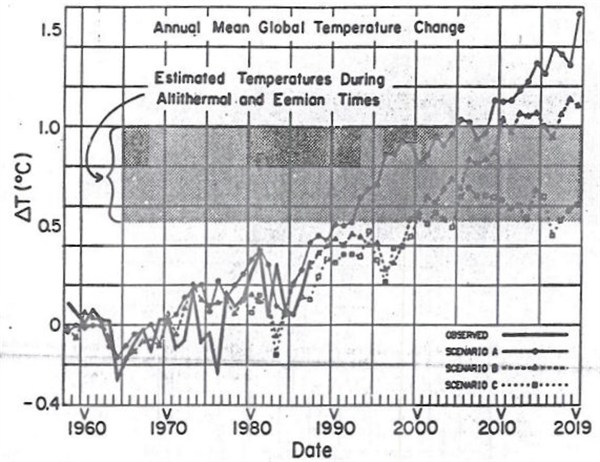

Temperature projection graph submitted to Congress by James Hansen as part of evidence of human caused global warming in 1988.

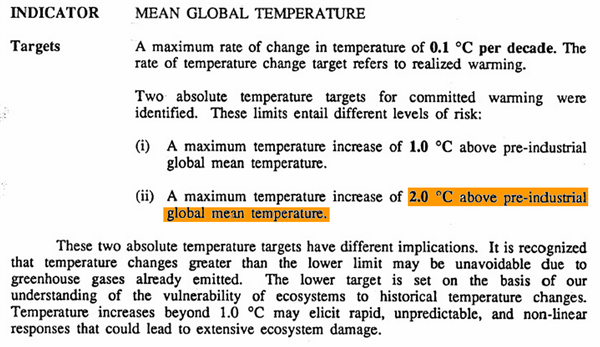

But Hansen didn’t offer Congress a definition of what constituted dangerous climate change. So in 1990 a team of researchers from the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) took it upon themselves to try and answer that question.

In a report looking at the potential impacts of of rising greenhouse gas emissions, they discussed a number of ways scientists could measure the world’s efforts to limit climate change. They suggested curbing sea level rise or restricting the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere as two options. Another was to use global warming as a guide for where to set an overarching limit.

Based on scientific understanding at the time, SEI suggested that to avoid the worst impacts of climate change, a limit should be set at two degrees. But, the report warned, the higher the temperature rise, the bigger the risks from climate change.

“Temperature increases beyond 1.0°C may elicit rapid, unpredictable, and non-linear responses that could lead to extensive ecosystem damage,” the report said, suggesting there is nothing necessarily ‘safe’ about a two degree limit.

An early reference to the two degrees limit in the Stockholm Institute’s Targets and Indicators of Climate Change report.

Two degrees and international climate politics

Soon after the institute’s intervention, the idea of a two degrees limit started to appear in more mainstream political settings.

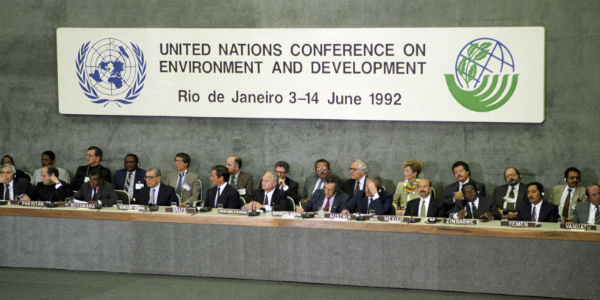

In 1992, world leaders signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. Article 2 of the convention commits countries to stabilising “greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system”.

It stopped short of defining the level at which climate change became “dangerous”, however, despite growing calls for two degrees of warming to be set as a limit.

World leaders at the 1992 Earth Conference in Rio de Janeiro. Credit: United Nations

Then, in 1996, the European Council of environment ministers became the first political body to lend formal support. It declared that “global average temperatures should not exceed 2 degrees above pre-industrial level”.

Signatories to that statement included figures who now sit at the forefront of international climate politics – the UK’s John Gummer, now chair of the UK’s Committee on Climate Change, and Germany’s Angela Merkel, who is currently spearheading Germany’s transition to renewables.

Germany’s current chancellor, Angela Merkel, representing the country as environment minister at the first UNFCCC meeting in Berlin in 1995. Credit: International Institute for Sustainable Development

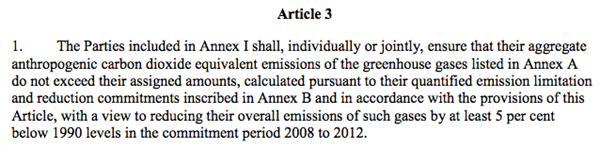

A year later, 193 countries signed the world’s first binding agreement to cut emissions: the Kyoto Protocol. The treaty set limits on countries’ emissions, taking into account their historical contribution to climate change and ability to implement policies, with the aim of cutting global emissions five per cent on 1990 levels by 2012.

Negotiators spent the next decade trying to persuade countries to ratify the treaty,

figuring out how the protocol would work, and eventually trying to agree a replacement for the protocol as its 2012 expiration date loomed into view.

Article 3 of the Kyoto Protocol.

The Kyoto Protocol itself does not mention the two degrees goal. But media coverage at the time linked the treaty to two degrees. The New York Times, for example, pointed to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) conclusion that two degrees of warming would be dangerous, and described the protocol as the “beginning, not an ending” of the world’s efforts to prevent climate change.

In 2005, with the treaty ratified by almost 160 countries, the protocol formally came into force. It was hamstrung, however, by the absence of the world’s largest historical emitter: the US. The country remained open to the idea of a global climate deal, but didn’t want it to extend as far as the Kyoto protocol’s goals.

The two degrees limit was a particular point of contention for US diplomats, showing how symbolically important it had become. At the G8 summit in 2008, they reportedly culled references to two degrees from a draft summit conclusion proposed by chancellor Merkel.

This set the tone for the next five years of international climate negotiations. In 2009, attention turned to trying to agree a new deal to replace the Kyoto protocol. Negotiators hoped the deal would put binding obligations to cut emissions on all the world’s major emitters, including the US and China.

A joint-editorial published by 56 newspapers on the eve of 2009’s Copenhagen conference piled on the pressure, declaring:

“Climate change has been caused over centuries, has consequences that will endure for all time and our prospects of taming it will be determined in the next 14 days.”

Three newspapers running the joint-editorial calling for action at the Copenhagen climate summit.

The newspapers described what they saw as the reason for such urgency:

“The science is complex but the facts are clear. The world needs to take steps to limit temperature rises to 2°C, an aim that will require global emissions to peak and begin falling within the next 5-10 years. A bigger rise of 3-4°C – the smallest increase we can prudently expect to follow inaction – would parch continents, turning farmland into desert. Half of all species could become extinct, untold millions of people would be displaced, whole nations drowned by the sea.”

But despite media scrutiny and public backing for a deal being at an all time high, the conference ended in failure. Instead of a new, binding, global deal, world leaders agreed the Copenhagen Accord, which “recognised” the case for curbing emissions to prevent temperatures rising, but did not contain commitments to achieve the goal.

World leaders at the Copenhagen climate conference in 2009. Credit: White House

It took another year for the two degrees limit to be formally enshrined into international climate policy. The moment came in 2010, when countries signed the Cancun Agreements committing governments to “hold the increase in global average temperature below 2°C above pre-industrial levels.”

Countries have made only incremental progress towards this goal in recent years. But negotiators hope that 2015 will bring a new global climate deal, this time at a meeting in Paris.

The UK’s leader of the opposition and former energy and climate change secretary, Ed Miliband, who led the UK delegation in 2009, says that while the Copenhagen conference failed, Paris’s goal should be the same:

“… the answer is not to lower your ambition the next time round. It’s actually to say, ‘Well, we’ve still got the same ambition and we’re going to keep pushing and keep pushing until we actually succeed.'”

So, once again, world leaders will convene to try and find a way to prevent temperatures rising by more than two degrees, with the clock ticking.

A simple speed limit

Having been the totem of international climate negotiations for the past 40 years, it seems unlikely that the two degrees target will simply fade away post-2015. But the limit may find itself under pressure in a world that has to start adapting to warming, rather than just seeking to avoid it.

One of two degrees’ enduring strengths is its simplicity. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s co-chair, Thomas Stocker, previously told Carbon Brief:

“The power of the 2°C target is that it is pragmatic, simple and straightforward to understand and communicate, all important elements when science is brought to policymakers.”

Richard Betts, a Met Office scientist, compares two degrees to a speed limit. He explains in a short blog post:

“The level of danger at any particular speed depends on many factors… It would be too complicated and unworkable to set individual speed limits for individual circumstances taking into account all these factors, so clear and simple general speed limits are set using judgement and experience to try to get an overall balance between advantages and disadvantages of higher speeds for the community of road users as a whole.”

Scientists expect the impacts of climate change to become increasingly stark over the coming century, however. That may destabilise the idea that there is a “safe” level of climate change that we can stay below.

And the longer the world delays cutting emissions, the more challenging meeting the two degrees goal will become.

But even if stopping surface temperatures rising ceases to be climate politics’ only goal, analysts are likely to continue to measure politicians’ responses in similar terms – regardless of whether the world prevents warming of two degrees.

Tomorrow we’ll look at the prospects of the world staying below the two degree limit. And on Wednesday we’ll explore what could happen if we don’t.