Trade wind “tug of war” to blame as scientists lower odds of an El Niño

Roz Pidcock

01.08.15Roz Pidcock

08.01.2015 | 5:55pmThe Pacific weather phenomenon known as El Niño is now looking less likely after scientists today lowered the chances of an event in the next two months to 50 or 60 per cent.

El Niño has been hotly anticipated over the last few months. But today’s forecast by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) marks a drop in scientists’ confidence than an El Niño is on its way from a high of 90 per cent last year.

El Niño’s elusive behaviour has been somewhat of a surprise, with one leading expert calling today’s downgraded forecast the latest step in a “puzzling trajectory.”

Failure to respond

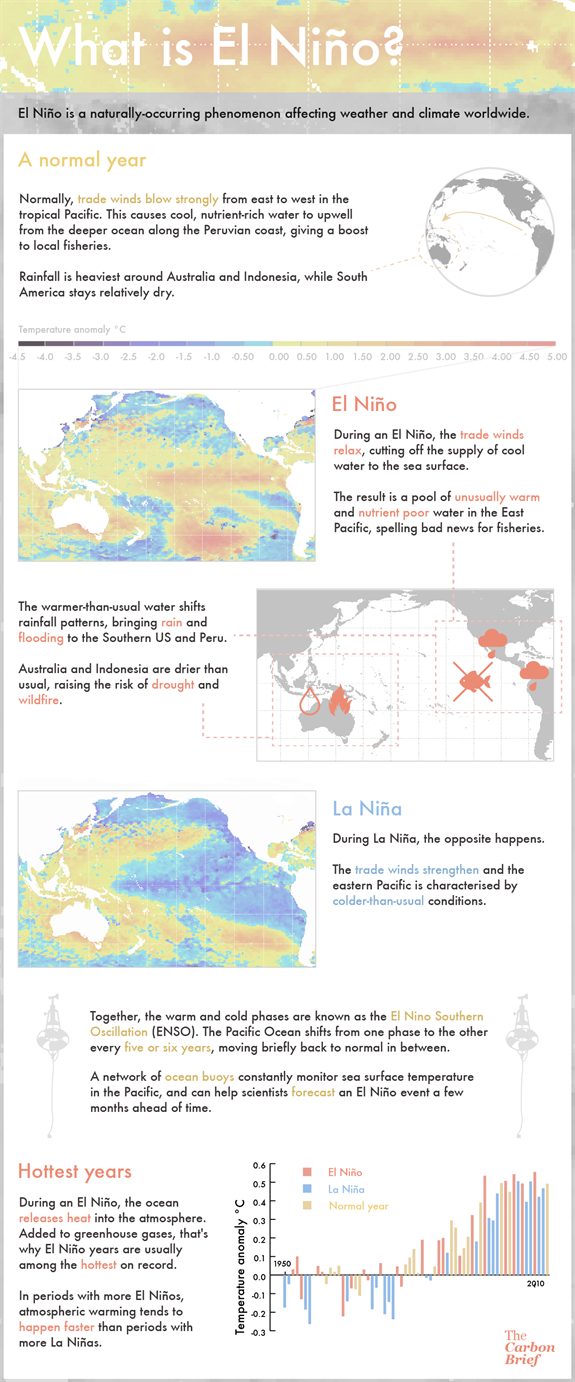

El Niño is marked by warmer-than-usual sea surface temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific and a weakening of the trade winds. This triggers a sequence of interactions between the atmosphere and ocean that amplifies the initial warming.

Despite strong initial signs last year that the Pacific Ocean was primed for an El Niño, scientists began to notice the atmosphere wasn’t responding in the way they might expect.

As Professor Kim Cobb from the Georgia Institute of Technology puts it, she and many others experts were “rather bullish” on the development of a strong El Niño event back in the late spring. But her opinion has shifted since then. She says:

“Since last Spring it has become clear that while many of the precursors were in place, the atmospheric feedbacks to early sea surface temperature anomalies never kicked into place.”

By July last year, forecasters across the world began dialling down their forecasts after the atmosphere “largely failed to respond” to rising sea surface temperatures.

Credit: Rosamund Pearce, Carbon Brief

“Tug of war”

Cobb describes another process at play in the region that she thinks could have interfered with the normal development of an El Niño.

While warmer-than-usual temperatures were developing in the Eastern Pacific, characteristic of the early stages of an El Niño, temperatures were also climbing in other parts of the Pacific.

This created a “tug-of-war” scenario in which trade winds couldn’t organise themselves into a coherent enough pattern to boost the nascent El Niño, she explains.

Professor Mat Collins from Exeter University agrees this year’s behaviour had scientists puzzled, saying:

“I think it remains a bit of a mystery about why the atmosphere response never got going.”

Collins’ explanation for what could be going on echoes Cobb’s suggestion that the trade winds essentially got confused. He says:

“One hypothesis is that we have actually been experiencing a type of ‘basin-wide’ El Niño event, like in 2009, with moderately warm sea surface temperatures all across the basin. Thus, sea surface temperature gradients weren’t really affected â?¦ and the trade winds remained strong.”

Cooling off

Looking at the ocean and atmosphere together, conditions in the Pacific don’t look favourable for an El Niño and continue to look “neutral” for the moment, today’s forecast says.

Sea surface temperatures are still higher than average, which means the chances of an event developing in the next couple of months remains above 50 per cent. If an El Niño does emerge, it’s likely to be a weak event that ends in early Northern Hemisphere spring, the scientists say.

Though El Niño may arrive with more of a whimper than a bang, it’s important to look at the phenomenon in the context of of continued greenhouse gas warming, Cobb says:

“[E]ven modest El Niño warmings, such as that currently underway in the central tropical Pacific, occur on top of an overall warming trend â?¦ 2014 will likely be the warmest year on record even though it is only a weak El Niño year.”

In other words, a planet that’s continuing to warm means that it’s looking like 2014 will beat 1998 to the top spot, even though that year saw an extremely strong El Niño event.