Tonga volcano eruption raises ‘imminent’ risk of temporary 1.5C breach

Ayesha Tandon

01.12.23Ayesha Tandon

12.01.2023 | 4:00pmThe eruption of Tonga’s underwater volcano in 2022 may cause global temperatures to rise, raising the risk that at least one year in the next five will temporarily exceed the 1.5C warming threshold, new research finds.

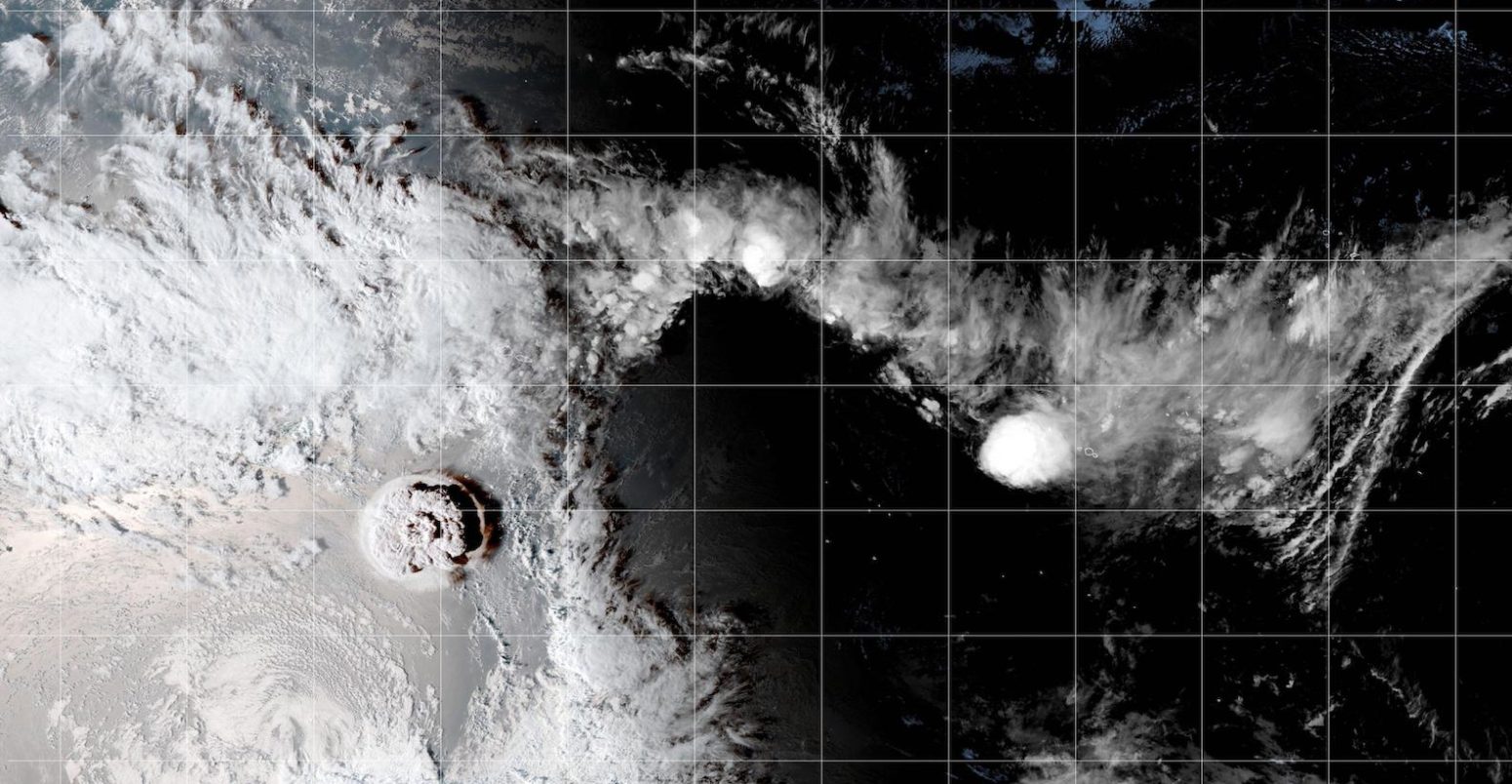

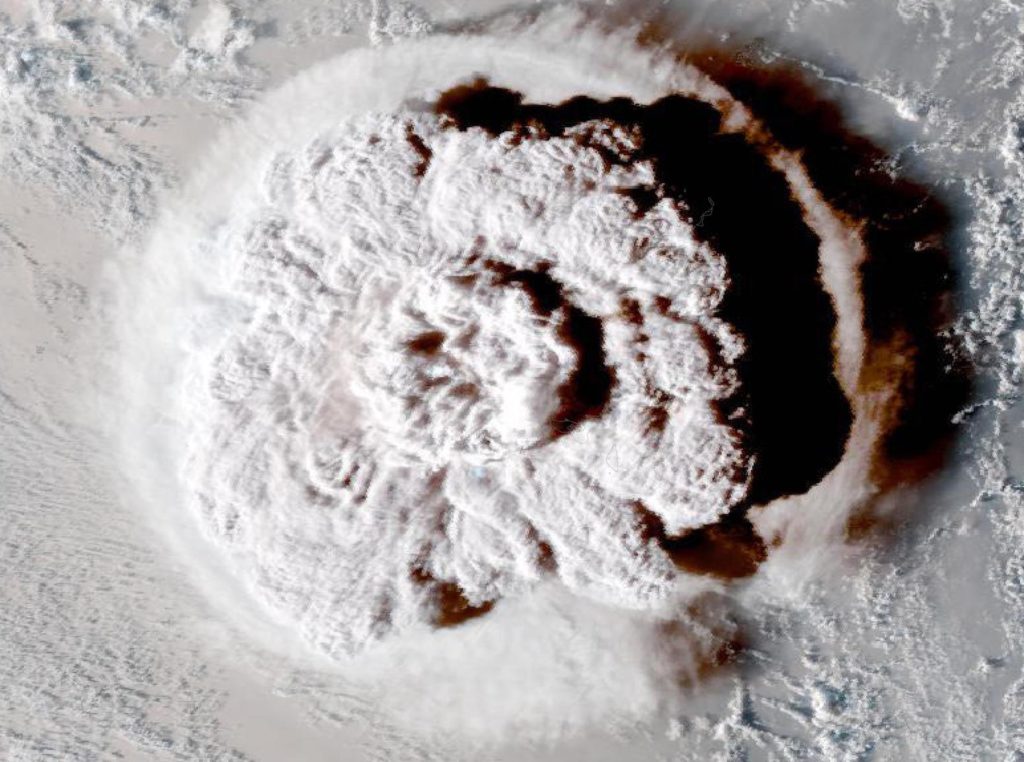

On 15 January 2022, an underwater volcano in Tonga – the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai – erupted violently, releasing billowing plumes of soot, water vapour and sulphur dioxide high into the atmosphere.

Major volcanic eruptions typically cool the planet temporarily, because, until they dissipate, sulphur dioxide particles reflect sunlight away from the planet. However, the study – published in Nature Climate Change – finds that the Tonga eruption in the south Pacific expelled an unprecedented amount of water into the atmosphere.

Water vapour is a greenhouse gas and so “it is possible that over a multiyear period Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai will cause a temporary increase in global surface temperatures”, the paper says.

The study says that, before the eruption, there was a 50-50 chance that global temperatures would exceed 1.5C above pre-industrial levels at least once by 2026. In its aftermath, the likelihood of exceeding this threshold has increased by seven percentage points – making “imminent 1.5C exceedance” more likely than not.

The authors stress that temporarily crossing the 1.5C threshold would not equate to missing the Paris Agreement target, which concerns long-term temperature trends. Nevertheless, the paper says “the first year which exceeds 1.5C will garner substantial media attention, even if a portion of this results from Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai”.

Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai

On 15 January 2022, an underwater volcano in the Pacific Ocean’s Tongan archipelago called the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai erupted violently. The blast ranked a six on the volcanic explosivity index, making it the most violent eruption anywhere in the world since Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991.

The explosion was heard across the ocean in Alaska, around 6,000 miles away, and triggered tsunami waves that reached as far as Russia, the US and Chile. A cloud of ash, gas and water was ejected some 57km into the atmosphere – the highest plume ever recorded from a volcano.

Ash from the eruption blanketed nearby islands, forcing many people to evacuate to the main island. Around 84% of Tonga’s population were impacted by ash and tsunami waves in the immediate aftermath of the eruption, and two Tongan nationals were killed.

Aside from these local impacts, the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai stands apart from its predecessors for another important reason.

Usually when a volcano erupts, the plumes of dust and aerosols reflect sunlight away from the planet, causing surface temperatures to drop. For example, when Mount Pinatubo erupted in 1991, global temperatures temporarily dropped by 0.5C. However, the Tonga eruption has had the opposite effect.

Dr Stuart Jenkins, from the University of Oxford’s department of Atmospheric, Oceanic and Planetary Physics, is the lead author of the “brief communications” study. He explains that the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai caused surface warming thanks to the unusual composition of its plume:

“Most large eruptions are dominated by their sulphur dioxide emissions, which cool the planet temporarily as they scatter incoming sunlight. The Tonga eruption was unusual because instead it released a large amount of water vapour into the stratosphere – a powerful greenhouse gas – with little sulphur dioxide emissions.

“Pinatubo and Tonga actually may have opposite warming responses, which makes the Tonga volcano particularly interesting in the context of other recent eruptions.”

In total, the study finds that the blast projected just 0.42m tonnes of cooling sulphur dioxide aerosols into the stratosphere – a layer of the atmosphere begins around 10km above the surface of the Earth, and extends upwards for around 40km. Meanwhile, it expelled a total of 146m tonnes of water, raising the water vapour content of the stratosphere by 10–15%.

“The Tonga eruption was definitely unusual,” says Dr Mark Schoeberl – a researcher from Columbia’s Science and Technology Corporation, who has led separate analysis on the Tonga eruption’s water plume. He tells Carbon Brief that Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai “lofted an unprecedented amount of water into the mid-stratosphere”.

Dr Luis Millán from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory has also led separate research into Tonga eruption’s hydration of the stratosphere. He tells Carbon Brief that the eruption injected enough water into the stratosphere to fill 58,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

The water vapour then spread out across much of the stratosphere, the study says. It adds that the warming effect of the water vapour outweighed the cooling effect of sulphate aerosols, causing global surface temperatures to rise temporarily.

1.5C threshold

Since its eruption in January 2022, scientists have investigated the volcano’s impact extensively – including the unprecedented height of its plume, its impact on atmospheric circulation and the effect on the global energy balance. However, this study is the first to investigate what the temporary warming means for global temperature thresholds.

The authors use a radiative transfer model to assess how the Tonga eruption changed the balance of energy entering and leaving the surface of the earth, and find a warming effect of 0.12 Watts per square metre immediately following the eruption.

They then use a climate model to estimate global temperature change over the coming decade, assuming that the amount of water in the stratosphere decreases linearly from January 2022 to January 2029.

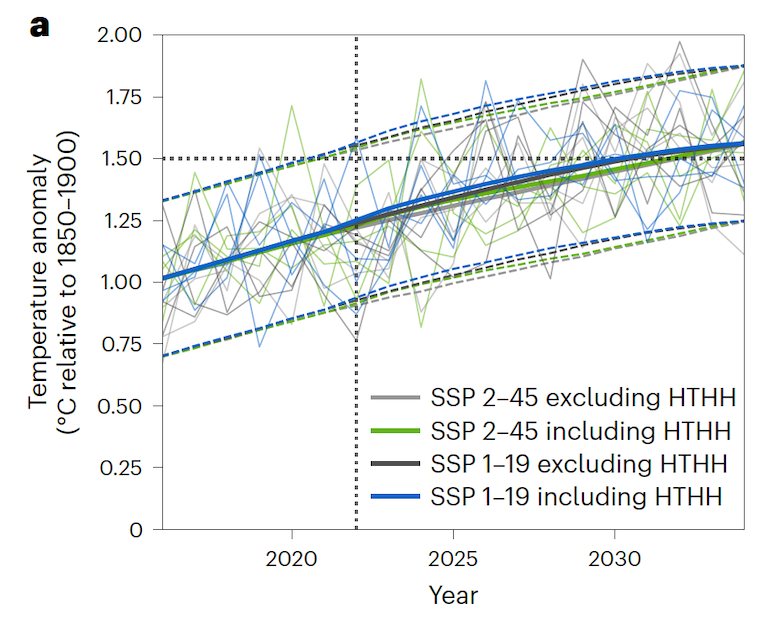

The plot below shows the change in global average surface temperature compared to the 1850-1900 average, both with and without the impact of the Tonga eruption, over 2015-35, under two different scenarios that explore future climate change.

The plot shows the low-emissions SSP1-1.9 scenario with (dark blue) and without (dark grey) the impact of the Tonga volcano. It also shows the moderate-emissions SSP2-4.5 scenario with (green) and without (light grey) the impact of the Tonga volcano. The main results are shown with thick coloured lines. Thin lines show interannual variability and dashed lines show the 5th-95th percentile range of results.

Next, the authors ask: what does this temperature rise mean for the 1.5C warming threshold?

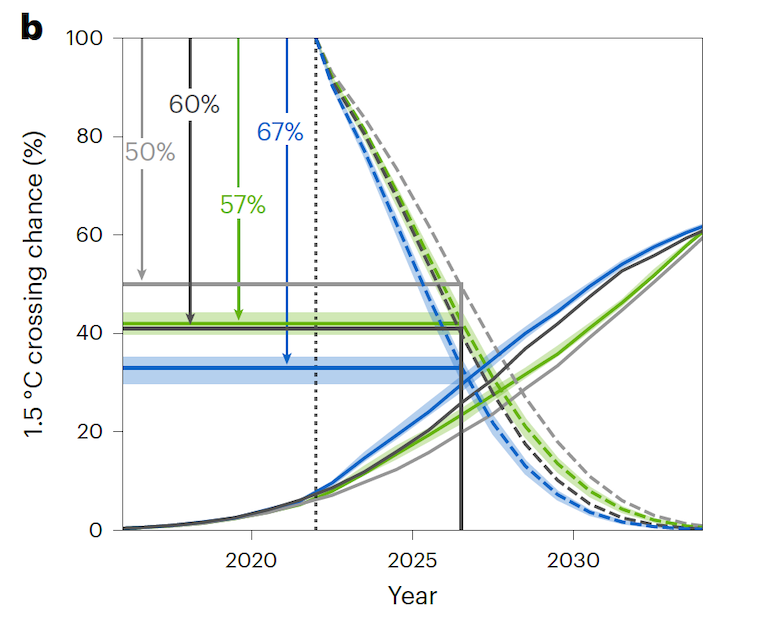

Last year, the World Meteorological Organization estimated that there is a 50-50 chance of global temperatures temporarily crossing the 1.5C warming threshold in at least one year between 2022 and 2026. However, this estimate does not take the warming effect of the Tonga eruption into account.

The plot below shows the likelihood of global surface temperatures exceeding the 1.5C threshold over 2015-35 (solid lines) under the four scenarios investigated above, and the cumulative probability that no year has yet exceeded 1.5C (dashed lines) for each.

The plot shows that the Tonga eruption increased the chance of at least one year over 2022-26 years exceeding the 1.5C warming threshold by seven percentage points. In other words, under the SSP1-19 scenario, the probability has risen from 50 to 57%, while under SSP2-45, it has risen from 60 to 67%.

Prof Pasquale Sellitto from the Interuniversity Laboratory of Atmospheric Systems has also published separate research on the radiative impact of the Tonga eruption. He tells Carbon Brief that the work is “a very interesting extension of previous studies on the climate impact of this exceptional eruption”, adding that its results are “very reasonable”.

However, he flags two areas where the study could be improved. Firstly, he says the paper assumes that water vapour injected into the atmosphere is “globally well mixed”, whereas in reality, the plume was “confined in the southern hemisphere”.

Secondly, the paper omits the cooling impact of the sulphate aerosols injected into the atmosphere, stating that “the sulphur dioxide deposit is substantially smaller than the accompanying water vapour deposit”. However, Selitto says that “the Hunga Tonga perturbation of stratospheric aerosol is actually the largest since the Pinatubo eruption in 1991”.

He concludes:

“I think that Jenkins et al. is a very nice starting point to estimate the global mean surface temperature impact by the Hunga Tonga eruption in 2022, but more studies are required in the future to make more precise estimations.”

Similarly, Millán says that if the 1.5C threshold is crossed in the coming years, more model runs will be needed to “discern the small Hunga’s contribution from the anthropogenic one”.

Paris agreement

In 2015, the United Nations delivered the Paris Agreement – an international agreement to limit global warming to 2C above pre-industrial temperatures, while aiming to keep warming below 1.5C. These temperature thresholds have been key benchmarks for progress on tackling climate change ever since.

As such, the paper says that “the first year which exceeds 1.5C will garner substantial media attention, even if a portion of this results from Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai”.

However, it emphasises that the common interpretation of the Paris Agreement is that its temperature limits refer to the long-term global warming attributable to human influence – and not the added effect of natural climate variability caused by events such as volcanic eruptions. As such, temporarily crossing the 1.5C threshold over 2022-26 due to the Tonga eruption will not dictate the success or failure of the Paris agreement.

Jenkins tells Carbon Brief the impact of the eruption on global temperatures is temporary, and will fade over five to 10 years. He adds:

“Tonga is only contributing a very small amount to the surface temperature anomaly today. We will not see the impact of Tonga on climate change events like droughts or floods, the effect is simply too small.”

Jenkins et al. (2023) Tonga eruption increases chance of temporary surface temperature anomaly above 1.5C, Nature climate change, doi:10.1038/s41558-022-01568-2