Ros Donald

16.09.2014 | 5:50pmInvestment choices in global infrastructure over the next 15 years will determine the future of the world’s climate system.

That’s the conclusion of the New Climate Economy report , which concludes that if investment goes into advanced technologies, there need not be a trade-off between improving living standards around the world and the health of the climate. Indeed, those investments could cost the same as ones we’d need to make anyway.

In 2013, the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate was created to investigate whether the global economy can continue to grow while tackling the risks of climate change. It’s not an obvious combination.

On one hand, fossil-fuelled growth – especially in fast-developing countries like China – has pushed greenhouse gas concentrations to record levels. On the other, governments justifiably want to improve the living standards of their populations. Since the Industrial Revolution, that has equated with rapid emissions growth as energy networks expand and production ramps up.

But new technological advances mean the apparent conflict between the two goals is a “false dilemma”, according to the chair of the commission and former president of Mexico, Felipe Calderon. Speaking at the launch, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon told the audience the two goals could be “mutually reinforcing”.

Cities: public transport and new materials

Cities are growing at an unprecedented rate, and that’s set to continue over coming years. Urban areas already generate around 70 per cent of global energy use and energy related emissions.

Urban sprawl forces people into cars or punishingly long journeys into the centre. And at the moment, urban growth is unplanned, meaning cities are set to become less and less efficient, with worsening transport links.

High energy prices hit these areas particularly hard.The report cites the example of sprawling suburbs like Victorville, outside Los Angeles, which became unviable when fuel prices doubled in 2008, seeing 70 of new homes for sale in foreclosure by July 2009.

The report says cities should become more compact, focused around mass transport links. Approach urbanisation like that, and cities could reduce the amount they need to spend on urban infrastructure by $3 trillion over the next 15 years. The image below contrasts the emissions levels of Atlanta versus the relatively compact Barcelona.

The transport links of the future need not be markedly different to the ones we have now. The report finds that bus rapid transit systems can carry up to two million passengers a day at less than 15 per cent of the costs of a metro.

Space-age technologies aren’t necessarily that far off either. The report says Siemens has identified 30 market-ready low carbon technologies such as LED street lighting, new building technologies and electric buses. The company projects that adopting these technologies across 30 of the world’s megacities could create more than two million jobs and avoid three billion tonnes of cumulative greenhouse gas emissions.

Energy: renewables and efficiency

Energy use worldwide has grown by more than half since 1990, and 87 per cent of our energy supply is provided by fossil fuels. If we want to prevent temperatures rising by more than two degrees above pre-industrial levels – the internationally agreed goal – and meet energy demand, we’re going to have to lower that percentage fast.

One way to cut power sector emissions is to use less of it. This approach is often considered the low-hanging fruit of carbon policy, but as the report’s global programme director, Jeremy Oppenheim observes: energy efficiency is “always the bridesmaid but not often enough the bride”.

Energy efficiency doesn’t just cut emissions. In developed nations, it’s already the biggest source of ‘new’ energy supply. There’s a lot of untapped potential there, however, in developed and developing countries. India’s energy requirements in 2030 could be as much as 40 per cent greater in a high-efficiency example, the report says.

Raising efficiency is also a big part of introducing low carbon generation to grids around the world. New materials have driven down the cost and improved the performance of wind and solar energy, leading to a surge in global investment in renewables. Other options are becoming viable, too: geothermal energy and energy from waste have expanded recently, while China is the global leader in solar thermal heat systems and Brazil and Morocco are installing solar water heaters in low-income housing.

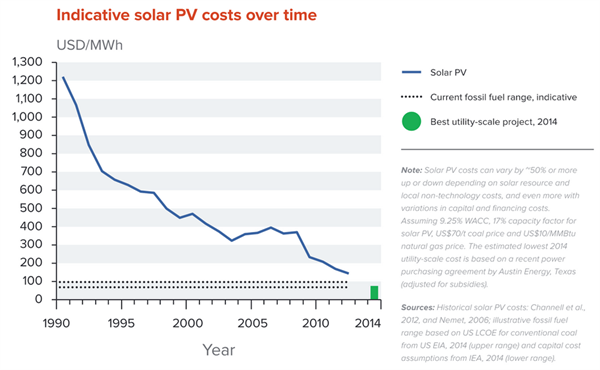

The graph below shows just how fast the cost of solar panels has fallen due to improved technology:

But grids will have to adapt to deal with new generation patterns. Innovations in technologies such as energy storage and smart grid management will be important, as will new business models

Low carbon energy sources can discourage governments due to their high up-front costs, but they yield multiple benefits including reduced operating costs and better public health, the report points out. It estimates that the cost of air pollution’s health impacts often exceed the cost of moving to lower-carbon energy sources. At the most extreme end of the scale, mortality from air pollution is now valued at 10 per cent of GDP in China.

Land use: restoring degraded land and breeding supercrops

The way we use land provides the world with food, timber and other important products – but it also accounts for a quarter of global emissions. And global agricultural productivity will have to increase by almost two per cent per year to keep up with projected demand. At the same time, roughly a quarter of the world’s agricultural land is degraded and 13 million hectares of forests are cleared each year.

Curbing deforestation is going to be crucial in maintaining the world’s ability to sequester carbon. So more land will have to be found elsewhere. The report finds that if 12 per cent of degraded agricultural land were restored, deforestation would be avoided, smallholders’ incomes could grow by $35 to 40 billion per year and feed 200 million people a year within 15 years.

New crop species can also increase yields. In Brazil’s Cerrado, an area considered unprofitable due to poor soils, new soybean varieties were developed that were resistant to the tropical climate, achieving yields two to three times larger than those in more fertile parts of Brazil.

Now, new technologies mean seed developers can screen enormous volumes of material for desired traits and cross-breed them into seeds.

By breeding specialised crops and improving management practices, farmers can help reduce land degradation, offering greater productivity and resilience to climatic hardships like drought. In addition, farmers can add organic matter to soil and control water runoff, improving water retention and soil fertility.

If agriculture can be sustainably expanded without a negative impact on emissions, the report says, agricultural exports could support development in both poor countries and large economies like Indonesia, Brazil and even the US.

Spending the money

The report offers policymakers a choice: spend $90 trillion on the infrastructure we need, but follow the business-as-usual path, or invest that money in a dramatic change for the global economy.

If policymakers want to go for the latter, there will have to be significant support for workers in traditional industries whose jobs are threatened. To ensure that the incentives are there for technological advancement and investment, they will also have to provide policy certainty – something that hasn’t been forthcoming in recent years, as subsidies fluctuate and policy measures are repealed or changed.

The report outlines how current and future investments can change the economy works without sacrificing improved living standards. It seems like an obvious choice, but a huge political effort will be required to see that vision come to fruition.

-

The technologies that could grow the global economy and save the planet, at no extra cost