The Lancet: Extreme heat threatens ‘systemic failure’ of hospitals

Daisy Dunne

11.28.18Daisy Dunne

28.11.2018 | 11:30pmThe recent impact of climate change on heat-related diseases should be seen as a harbinger of future dangers posed to human health, a landmark report finds. These risks include the threat of a “systemic failure” of the world’s hospitals.

The findings come from the second Lancet Countdown report: an annual review of the scientific evidence of climate change’s effect on human health produced by 27 academic organisations from across the world.

Speaking at a press conference to mark the report’s launch, the authors added that the twin pressures of rising temperatures, which could cause influxes in patients suffering from heat-related illnesses, and extreme weather, which may damage infrastructure, could overwhelm health services.

Climate change is already having a notable impact on many other aspects of human health, the report finds, including by negatively affecting nutrition, mental wellbeing and labourers’ capacity to work outdoors.

However, there is “cause for hope”, the authors add, pointing to a ramping up of interest in low-carbon “healthy” diets and modes of transport in recent years, as well as the possible health benefits of a phase out of coal-fired power.

Feeling the heat

The report aims to take “the pulse of climate change and its health impacts” by tracking 41 indicators every year. Several of these indicators are linked to how extreme heat is increasingly affecting human health.

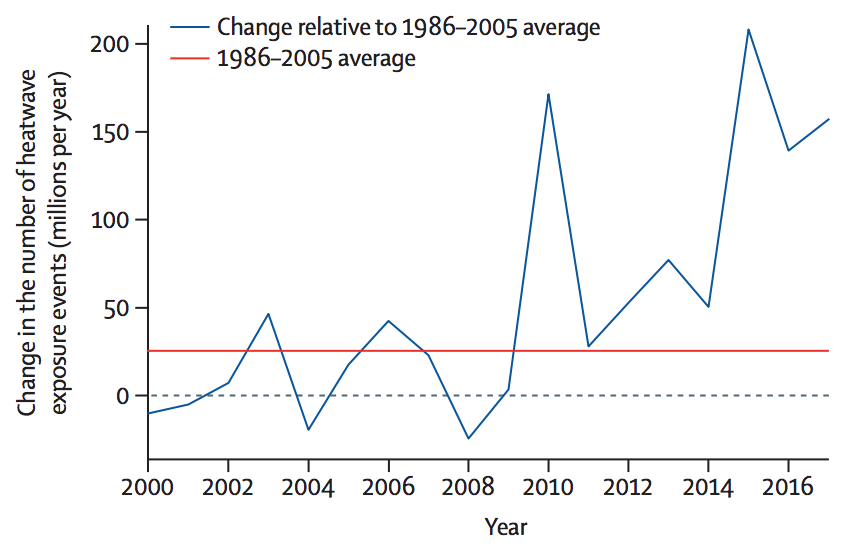

One finding is that, in 2017, the number of “vulnerable” people exposed to heatwaves increased by 157 million, when compared to the average number of people exposed from 1986-2005.

(Vulnerable is defined as being over the age of 65, while a “heatwave” is defined as three consecutive nights where temperatures are in the top 1% of the 1986-2005 average for the region.)

This means that 18 million more people were exposed to heatwaves in 2017 than in 2016, the report says. The chart below shows the change in the number of vulnerable people exposed to heatwaves from 2000 to 2017 (blue line), relative to the average for 1986-2005 (red line).

The change in the number of people exposed to heatwaves (or “heatwave exposure events”) in millions per year from 2010 to 2017 (blue line), relative to the 1986-2005 average (red line). Source: The 2018 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change

The rise in the number of vulnerable people exposed to heatwaves not only raises the risk of premature mortality via heat stress, but also the occurrence of chronic diseases, such as heart failure, says Dr Nick Watts, executive director of the Lancet Countdown. He told a press briefing:

“Heat has its effects directly on people – either in the form of heat stress and heat stroke, which I think we’re familiar with, but also in terms of dehydration. When you dehydrate someone enough, you end up with things like acute kidney failure; you end up exacerbating chronic renal failure and congestive heart failure.

“Some of those impacts from heat, either directly, or on our kidneys or hearts…we think really are the canary – ironically – in the coal mine, in terms of the early health impacts of climate change.”

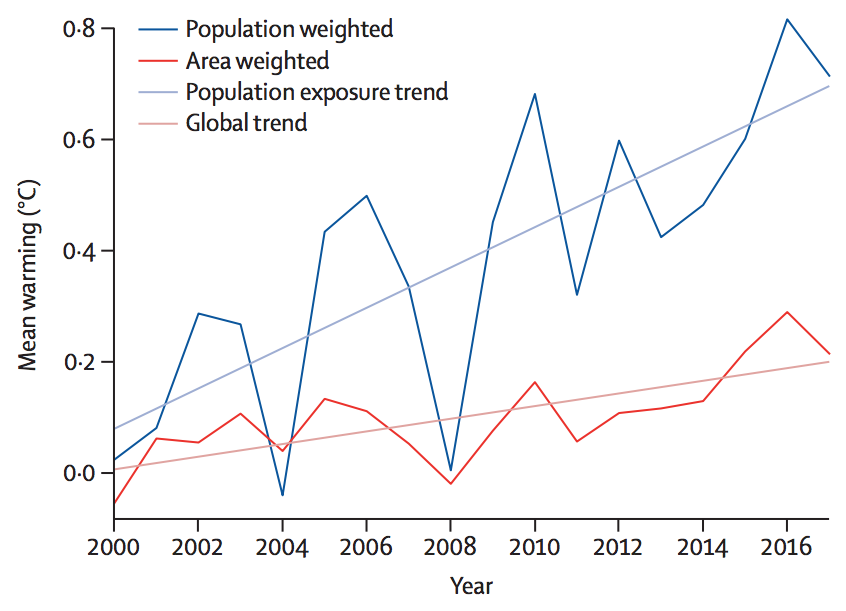

Another finding of the report is that, while the average global temperature has risen by 0.3C since the 1986-2005 period, the average temperature that vulnerable people are actually exposed to has risen by 0.8C.

This is shown on the chart below. It shows the rise in the global average surface temperature from 2000 to 2017, when compared to the average from 1986 to 2005 (red), alongside the rise in the temperatures that vulnerable people are typically exposed to (blue).

The rise in average global surface temperatures from 2000 to 2016 (red), alongside the rise in the average temperatures that people are exposed to (blue), relative to averages taken from 1986-2005. Source: The 2018 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change

One reason that the temperatures that vulnerable people are exposed to are higher than the global average is because warming is more severe over land than sea – and most people live on land. This is what Prof Peter Cox, a former report author and a climate scientist from the University of Exeter, told Carbon Brief last year when the first Lancet report was published.

However, this year’s analysis also suggests that vulnerable people tend to live in areas where temperatures are rising the fastest, Watts said:

“The climate is changing – but people are migrating and ageing into the areas that are worst affected by climate change. We are – in the way that populations are evolving – maladapting to the worst areas.”

The report finds that regions with ageing populations, such as the Mediterranean, are particularly vulnerable to heat-related health risks. In Europe, 42% of people aged over 65 are currently vulnerable to heat exposure, the report finds. This figure is likely to grow as warming worsens and populations continue to age.

Boosted bugs

Another set of indicators in the report track how climate change is altering the spread of infectious diseases. The authors do not have the capacity to track how warming is affecting every disease, say the authors, and so have selected a small number of “example” diseases to follow each year.

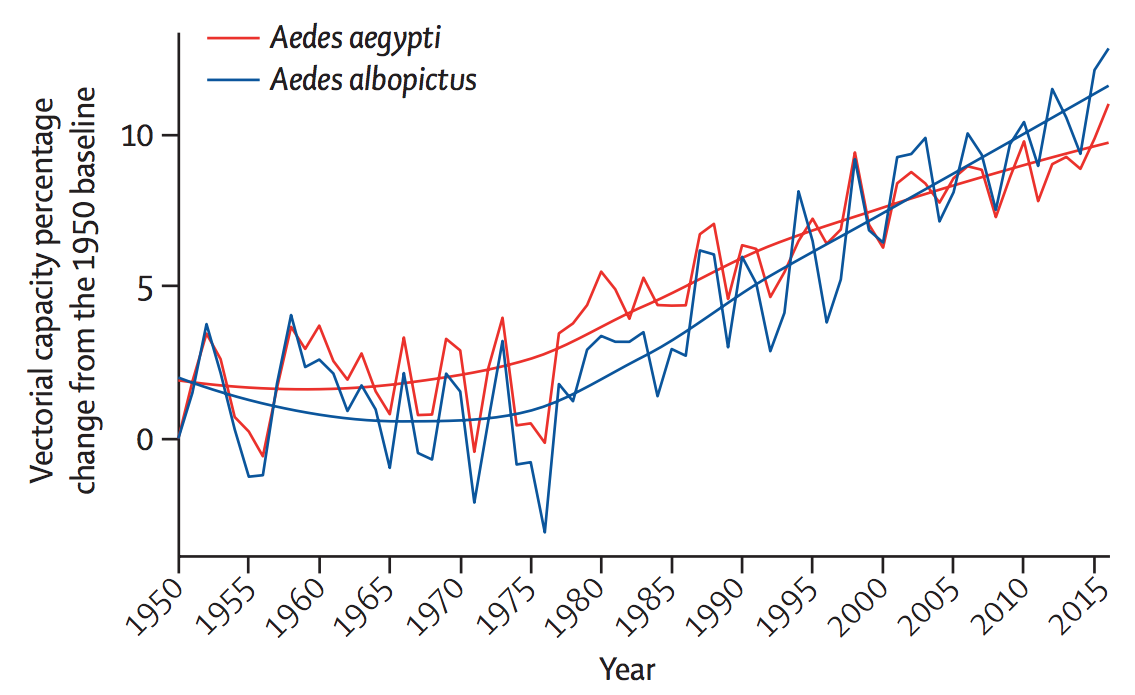

One of these is dengue fever – a mosquito-spread disease native to much of southeast Asia, central and south America, Australia and Africa.

Aedes albopictus, the Asian Tiger Mosquito, blood feeding on human skin. Credit: Dylan Becksholt/Alamy Stock Photo.

The report finds that the “global vectorial capacity” of dengue fever – a measure of the disease’s capability to spread and cause disease – reached its highest level on record in 2016.

This is indicated on the chart below, which shows the percentage increase in the vectorial capacity of dengue, when compared to its capacity in 1950. The chart shows results from two species of mosquito, including the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti; red) and the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus; blue).

The percentage change in global vectorial capacity of dengue fever from 1950-2016, when compared to levels in 1950, for the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti; red) and the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus; blue). Source: The 2018 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change

Warming temperatures can aid the spread of dengue by prompting mosquitoes to breed faster and feed on their hosts – humans – more frequently, according to Prof Hugh Montgomery, co-chair of The Lancet Countdown and a professor at University College London: “So it gets easier to spread the bug.”

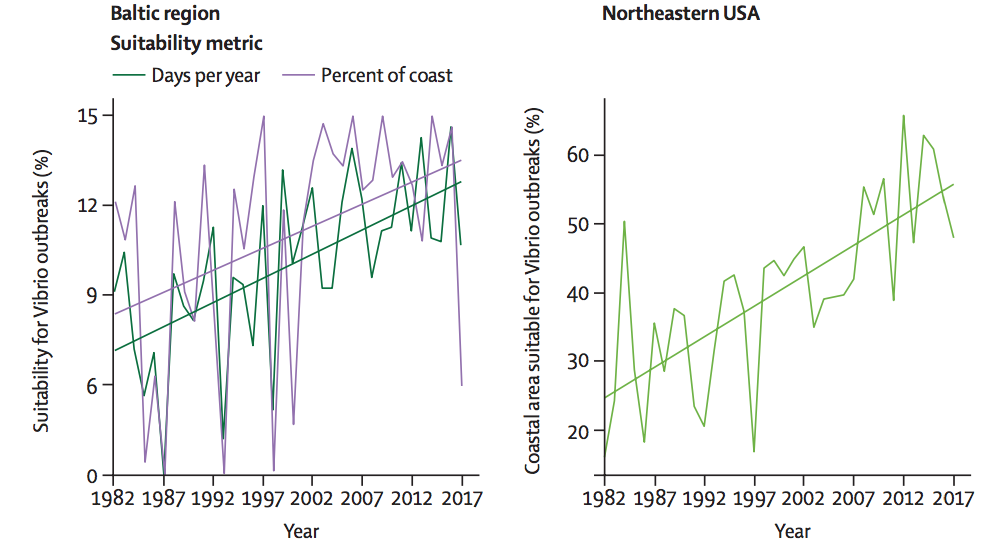

The report also finds that climate change could, in some coastal regions, be aiding the spread of water-borne “Vibrio” diseases. “Vibrio” is a type of bacteria that can cause several diseases, including the diarrhoeal infection cholera. Other illnesses associated with Vibrio include gastroenteritis, wound infections and septicaemia (blood poisoning).

The report notes that there is “a clear trend of rising suitability to Vibrio infections” that “is observable globally, notably in the northern hemisphere”.

The percentage of coastal area “suitable” for Vibrio infections in 2010 was 3.5% higher compared with the area available in the 1980s, the report says. However, two “high-risk focal regions” – the northeastern US and the Baltic region – saw much higher suitability increases of 27% and 24%, respectively, over the same time period.

This is indicated on the chart below, which shows changes in the percentage of coast area suitable for Vibrio infections for the Baltic region (left; purple) and the northeastern US (right) from 1982-2017. Changes to the number of days per year that have suitable conditions for Vibrio disease transmission (dark green) are also shown for the Baltic region.

Changes to the percentage of coast area suitable for Vibrio diseases in the Baltic region (left; purple) and the northeastern US (right) from 1982-2017. Changes to the number of days per year that are suitable for Vibrio disease transmission (dark green) are also shown for the Baltic region. Source: The 2018 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change

The increase in suitable habitat for Vibrio could be being driven in part by sea level rise, research suggests. This is because Vibrio thrives in “brackish” (slightly salty) water and, as sea levels rise, saltwater intrudes further into freshwater rivers and streams – creating more habitat suitable for Vibrio.

Rising sea temperatures could also be helping Vibrio to thrive, the report authors say.

It is worth noting that while the report tracks how climate change could alter the number of people exposed to infectious diseases, it does not track how many more people could be suffering from such illnesses, says report author Prof Elizabeth Robinson, an environmental economist from the University of Reading. She told the press briefing:

“We’re tracking exposure, we’re not tracking the actual health outcomes. [This is] because health outcomes depend on human systems and institutions, and to what extent countries are getting richer and coping more [with disease risk].”

Waning workforce

The report also tracks how rising temperatures are affecting occupational health – particularly for outdoor workers. Previous research suggests that increasing levels of heat and humidity are making working outside for long periods “intolerable”.

Using modelling, the authors find that, in 2017, the equivalent of 153bn hours of labour were likely lost as a result of extreme heat. Around 80% of these losses came from the agricultural sector, the report says.

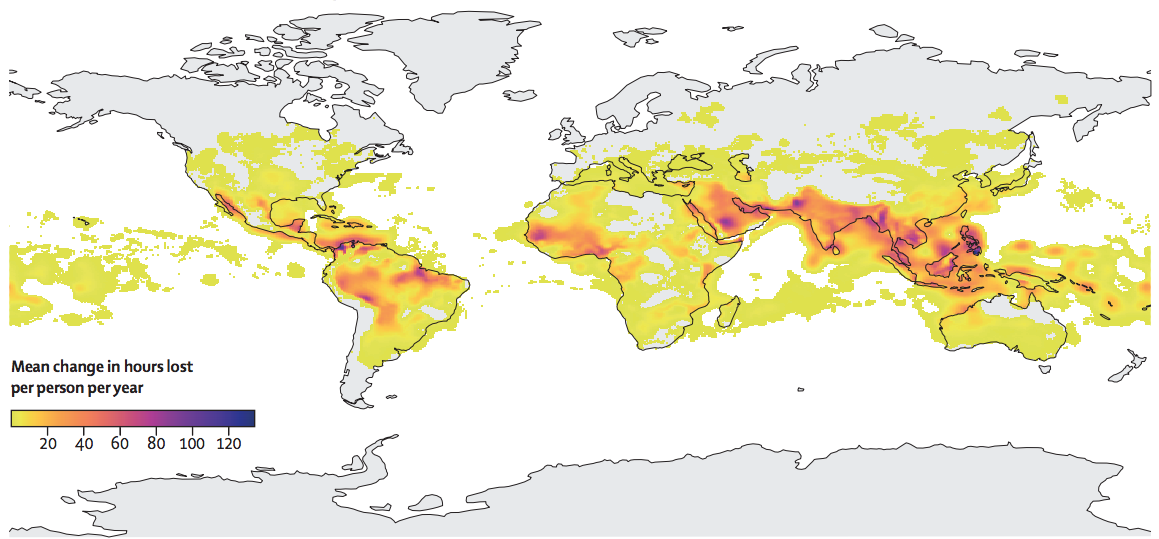

The distribution of hours lost from the agricultural sector are shown on the map below, where dark colours indicate a large increase in the number of hours lost (per person per year) from 2000-17, in comparison to the hours worked in 1986-2005.

Global projection of increases in the number of hours lost from the agricultural sector (per person, per year) from 2000-2017, in comparison to 1986-2005. Dark colours indicate high loss. Source: The 2018 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change

Losses to agricultural labour are “concentrated in already vulnerable areas in India, southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and South America,” the authors say.

Climate change could also be having a negative impact on crop yields in some countries, the report finds, which could have a knock-on effect on undernutrition. It finds that 30 countries are currently experiencing crop-yield declines. The report says:

“For some countries, where the yield gap – the difference between actual and maximum potential yield – is small, falling yields reflect the negative effects of climate change outweighing any technological improvement.”

This year’s report also offers, for the first time, “preliminary results” of how climate change could be impacting mental health. The report says:

“Climate change aggravates risks to mental health and wellbeing when the frequency, duration, intensity and unpredictability of weather-related hazards change. The resultant weather effects increase the number of people exposed or re-exposed to extreme events, and their consequent psychological problems, with suicide an extreme manifestation of trauma.”

Paltry preparations

In addition to tracking how climate change is affecting health, the report tracks the extent to which countries are adapting and preparing for future threats.

A survey undertaken by the report’s authors across 478 cities finds that 51% expect climate change to “seriously compromise” their public health infrastructure.

Health infrastructure, such as hospitals and ambulances, could face additional physical damages as climate change makes extreme weather more likely, Watts said:

“When we talk about public-health infrastructure being compromised, we usually talk about systemic failure. So, this is the shutdown of a hospital, or the shutdown of power to get to the hospital – but that’s OK because, perhaps, that hospital has a generator. But that generator was in the basement and the flood that shutdown the power in general also shut down the back-up of power.”

At present, around 4.8% of all adaptation funding is spent directly on public health infrastructure, the report finds. “Given the scale of the impacts we’re talking about here, that’s not enough,” Watts said.

However, despite major challenges ahead, there is “cause for hope”, Watts added:

“This is when we start to talk about the health benefits of coal phase out and the reductions in deaths from air pollution, and the investment in healthy transport infrastructure and diets.

“I don’t think we’ve had enough of a trend to say the world is going in one direction or the other just yet. But, what we do know is, whichever way we go, it [will] end up shaping the health profile of countries for the next century.”

Watts et al. (2018) The 2018 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: shaping the health of nations for centuries to come, The Lancet, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32594-7