As part of its series on how key emitters are responding to climate change, Carbon Brief looks at South Korea’s attempts to balance its high-emitting industries with its “green” aspirations.

Though still dwarfed by those of its neighbours China and Japan, South Korea’s rapid economic expansion over the past few decades has left it with a significant carbon footprint. It was the world’s 13th largest greenhouse gas emitter in 2015.

South Korean governments have championed the concept of “green growth” as a way of building the nation’s economy while also benefiting the environment.

However, the reality is that the nation’s economic success over the past few decades has been driven primarily by energy-intensive industries, which in turn are fuelled largely by coal.

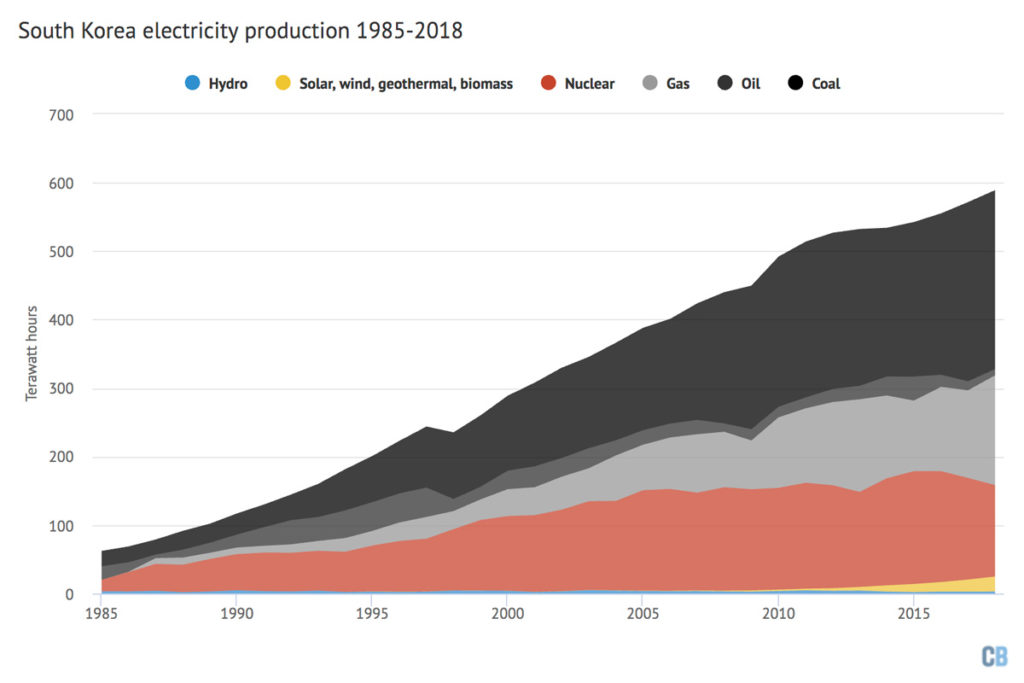

Nuclear is the only significant low-carbon energy source in South Korea, with renewables barely making a dent in its power supply.

As the country heads into an election amid the on-going coronavirus pandemic, mounting pressure has seen the ruling party propose the region’s first net-zero emissions target in its manifesto.

The coming months could profoundly shape the nation’s future emissions, with its leaders set to make key decisions about how best to recover from the economic damage caused by the virus.

(Update 22/04/2020: The incumbent Democratic Party won a “landslide” victory in an election that was seen as a demonstration of voters’ satisfaction with the government’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic. This success will allow President Moon Jae-in to push ahead with his party’s “green new deal” agenda, which includes a 2050 net-zero target, an end to coal financing and the introduction of a carbon tax.)

(Update 11/05/2020: The outline of a “new deal” released by the South Korean government suggests the nation’s coronavirus recovery package will have a digital focus, emphasising investment in artificial intelligence and fifth-generation (5G) wireless technology. However, a draft energy plan covering the next 15 years shows “green” issues are still on the table, with a target of 40% renewable power by 2034 and the replacement of some coal capacity with liquefied natural gas.)

(Update 28/10/2020: President Moon Jae-in has announced a net-zero target, committing to “go toward carbon neutral by 2050” in a speech to the national assembly. “We will replace coal power with renewable energy and create a new market, industry and jobs,” he said. The pledge will be supported by “green new deal” projects, which will involve the government funding renewables, electric vehicle manufacture and clean hydrogen production. The move was welcomed by environmental groups that had previously criticised the government’s Covid-19 green recovery plans for not including ambitious, legally binding climate targets.)

Politics

Since the hostilities of the Korean War ended in 1953, the Republic of Korea – one of the “four Asian tigers” – has grown from a developing country into a significant economic power with the 12th-highest GDP in the world.

In particular, it has become known as a major exporter and an industrial leader in many sectors, including electronics, cars, shipbuilding and steel.

Following decades of authoritarian rule, South Korea held its first free parliamentary election in 1988. Its two major political parties are the conservative United Future Party and the ruling liberal Democratic Party, with Moon Jae-in serving as the nation’s current Democratic president.

The next legislative election, in which all 300 members of the country’s national assembly will be chosen, is set to take place on 15 April.

Not only will this election be the first since the Korean voting age was lowered from 19 to 18, it will also see some politicians elected via proportional representation for the first time, potentially allowing smaller parties to win more seats. However, the majority of candidates will still be chosen in a first-past-the-post system.

In recent months, the country has been afflicted by the coronavirus outbreak. But, unlike most other nations, South Korea appears to have been relatively successful in keeping the infection under control.

The election is, therefore, expected to go ahead as scheduled, with special measures, such as quarantined polling stations and voting in hospitals.

Commuters wear protective masks during the coronavirus pandemic, Seoul, South Korea, 28 March 2020. Credit: dbimages / Alamy Stock Photo.

South Korean climate-and-energy policy has primarily been viewed through the lens of “green growth”, in which continued economic development is fuelled by investment in clean technologies.

However, the nation has drawn criticism for not always matching its green-growth rhetoric with action. Proposed phaseouts of coal and nuclear have been prompted primarily by concerns about air pollution and safety, as opposed to climate.

With an election approaching, many environmental groups joined together to call for more action from the major parties, which they claimed have prepared virtually “no countermeasures” against climate change.

In March, a group of Korean youth activists sued the government over its climate framework, which they deemed insufficient to meet the nation’s Paris Agreement targets.

According to a 2019 study by the Pew Research Centre, South Koreans place climate change highest in their list of potential national threats. Of those polled, 86% agreed it is “a major threat to our country”, higher than cyberattacks, the influence of global superpowers and even North Korea’s nuclear programme, which only 67% viewed as a major threat.

Recent polling suggests 77% of voters would vote for political parties promising to respond to the threat of climate change in the general election.

Following calls from civil society, the Democratic Party revealed a manifesto in March with proposals for a “green new deal” and a 2050 net-zero emissions pledge if it wins the upcoming election. Among the proposed ideas are a carbon tax, an end to coal financing and more focus on renewables.

Such an idea is not entirely new in South Korean politics. The third biggest political party, the left-leaning Justice Party, as well as the nation’s Green Party, which currently has no seats in parliament, have both produced similar plans.

Together with these smaller parties, the incumbent Democratic Party is expected to secure the majority of seats in the election, which should allow President Moon to legislate the proposed policies.

This would make South Korea the first East Asian nation to set a specific timeframe for net-zero, although Japan has made a vague commitment to become decarbonised “as early as possible” in the second half of this century.

Assuming it wins re-election, the government is expected to make a significant announcement relating to its green new deal at the Partnering for Green Growth and the Global Goals 2030 (P4G) summit. This was due to have been held in the Korean capital of Seoul in June, but is now expected to be delayed due to the coronavirus pandemic.

After the global financial crisis of 2008, South Korea’ stimulus package was regarded as being particularly “green”, with 69% of spending set aside for projects such as renewable energy, energy efficiency and smart grids.

With the pandemic taking a significant toll on the Korean economy and the government announcing stimulus packages to soften the impact, there have been calls to once again ensure that recovery is undertaken with the climate in mind.

Paris pledge

South Korea’s greenhouse gas emissions stood at 640m tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) in 2015, according to Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) data that includes land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF).

Emissions from South Korea have more than doubled since 1990, and the country has some of the fastest growing levels in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

The nation ratified the Paris Agreement in November 2016. In its nationally determined contribution (NDC), submitted in June 2015 ahead of COP21 in Paris, South Korea said it planned to reduce its emissions in 2030 to 37% below business-as-usual (BAU) levels.

This target would amount to emissions levels that were 78% higher than in 1990 by 2030, not including LULUCF. It covers all economic sectors and allows for the use of international carbon offsets.

Previously, South Korea had stated under the Copenhagen Accord in 2009 that it would cut emissions by 30% below BAU by 2020, instead of 2030. This would have meant levels that were 80% higher in 2020 than 1990.

South Korea’s NDC has now replaced its Copenhagen pledge, which was far more ambitious as it aimed for similar emissions reductions but a decade earlier.

According to Climate Action Tracker (CAT), South Korea’s NDC is equivalent to limiting emissions in 2030 to 539MtCO2e, excluding LULUCF. As it stands, it estimates that current policies will bring the country’s emissions to 727-786MtCO2e by this date, 150-155% above 1990 levels.

CAT has, therefore, not only deemed South Korea’s Paris Agreement target “highly insufficient”, but also noted that the policies in place to achieve even this target are “critically insufficient”.

In order to achieve its 2030 target and, beyond that, aim for a “1.5C compatible” strategy, CAT says “South Korea will have to strengthen its climate policies considerably”.

This year, nations are expected – though not strictly required – under the Paris Agreement to come forward with updated plans that scale up the ambition of their original target. South Korea has yet to indicate whether it intends to meet this expectation.

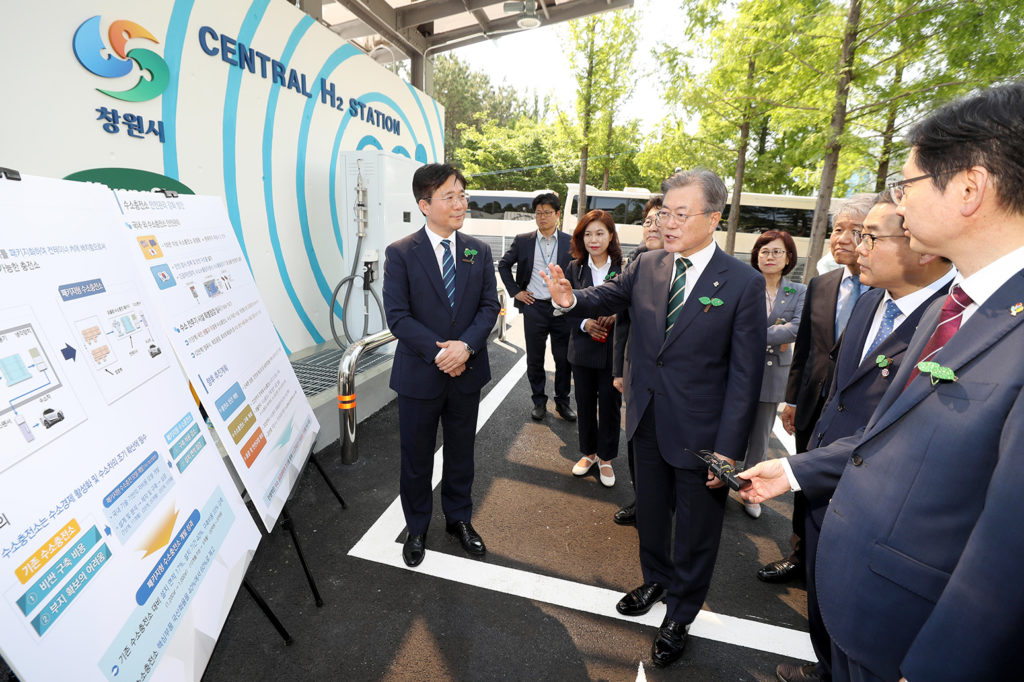

South Korean president Moon Jae-in is briefed on a hydrogen charging station in Changwon on 5 June 2019. Credit: Newscom / Alamy Stock Photo.

Sandwiched between the two major economies of China and Japan, both of which have been criticised on the international stage for climate inaction, South Korea has been the focus of relatively little attention.

However, the nation is coming under increased scrutiny, particularly over its future plans for coal power. One recent report by research group Climate Analytics prompted calls for South Korea to phase out coal completely by 2030 to be in line with the Paris Agreement target of limiting warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

At international climate negotiations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) South Korea is part of the Environmental Integrity Group (EIG), which contains just five other parties – Mexico, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Monaco and Georgia.

According to its members, this diverse grouping was created to push for progressive climate policies and bridge the gap between emerging and developed economies.

The South Korean government outlines its own role as “considering in a balanced manner both the historical responsibilities of the developed countries and the increasing trend of emissions for the developing countries”.

Finally, South Korea is home to the Green Climate Fund (GCF), a UN body based in the “international business district” of Songdo, near the north-western city of Incheon. The fund is the main mechanism set up for mobilising $100bn every year “by 2020” from richer countries to finance climate mitigation and adaptation in the developing world.

Hela Cheikhrouhou, former director of the GCF, said South Korea was an ideal location for the fund because: “It is an example of a country that has moved from being poor into an OECD country, and has an increasing awareness of the need to be mindful of the environment”. It was one of the first nations to pledge to the fund, with a $100m commitment that it has since increased to $200m.

North Korea

Seoul

Seoul

Incheon

Incheon

China

South Korea

Daegu

Daegu

Busan

Busan

Japan

200km

Graphic: Carbon Brief. © Esri

‘Green growth’ policies

In keeping with South Korea’s rapid industrialisation over the past few decades, the nation’s approach to climate and energy is best summarised by the principle of “green growth”.

Upon the inauguration of President Lee Myung-bak in 2008, he made it clear his overarching philosophy would be based on clean-energy technologies and environmentally friendly development in order to fuel long-term economic growth. In a speech at the time, he said:

“If we make up our minds before others and take action, we will be able to lead green growth and take the initiative in creating a new civilisation.”

This was reflected in the flagship Framework Act on Low Carbon, Green Growth (pdf), which was passed in 2009 and provided the legislative framework for emissions targets and renewable energy expansion, as well as the basis for a carbon trading system.

A five-year plan implemented the same year saw South Korea commit 2% of its GDP through to 2013 to invest in the green economy, which included investing in renewable energy, smart grids and green homes.

According to the World Bank, this focus on green investment is partly credited with the nation’s early recovery from the global financial crisis.

From the outset, South Korea emphasised the importance of leading by example and bodies such as the OECD welcomed its “new national growth paradigm” with the hope it could be imitated by other emerging economies.

Former President Lee also created the Global Green Growth Institute as a means of testing the principles of green growth. This international thinktank has been described as a “powerful expression of Korea’s middle-power identity”.

However, with South Korean emissions reduction targets likely to be missed and renewable energy lagging far behind coal, there remains a question mark over the success of its “green growth” transition.

In fact, even as much of Europe and North America progressed towards cleaner power over the last decade, the carbon intensity of electricity in South Korea increased as it relied more heavily on coal.

Around the time of its green growth agenda launch, the Korean government also introduced its first energy “master plan”. Since then there have been three iterations of these plans, with the most recent published in 2019 and setting targets up to 2040.

Together with a plan for the power sector released in 2017, this strategy sees South Korea reaching 20% renewable electricity by 2030 and 30-35% in 2040, up from 3% in 2017. This is a sharp increase on the target of 11% by 2035 under the previous master plan.

The government’s target has been widely dismissed as “unrealistic”, with analysis by various organisations including CAT and consultancy group Wood Mackenzie concluding that South Korea is unlikely to hit its targets on its current trajectory.

‘New and renewable’ energy

Energy is by far the biggest contributor to South Korea’s greenhouse gas emissions (see infographic above), but efforts to decarbonise the sector have been slow and the nation remains heavily reliant on fossil fuels, particularly coal.

President Moon himself has said the nation is “embarrassingly behind” others when it comes to renewable energy.

The chart below shows that for the power sector, virtually all the low-carbon electricity in South Korea comes from its nuclear facilities, with renewables, such as solar, wind and hydropower, making a small contribution.

Monitoring of the nation’s progress on renewables is muddied slightly by a uniquely South Korean classification system that treats “new energy” the same as “renewable energy”.

This means laws regulating renewables in South Korea also cover sources that are not necessarily renewable, including coal-fired integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC), fuel cells and industrial waste incineration.

According to South Korean NGO Solutions for Our Climate (SFOC), this concept “has long been considered problematic” and has recently been somewhat amended, with “waste energy from non-renewable waste” now excluded.

However, even taking this into account, Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO) figures show “new and renewable energy” only accounted for 6.2% of total electricity generation in 2018. Waste energy and bioenergy make up the bulk of this, with solar and wind accounting for just 1.9%.

New and renewable energy in South Korea was initially supported with a feed-in tariff, but this was replaced in 2012 with a renewable portfolio standard (RPS). This requires major electric utilities to meet renewable and new energy targets, aiming to increase their share of electricity generation to 10% in 2023.

Issues with the RPS have been identified as partly responsible for the pace of progress on renewable energy in South Korea, not least because it is still subsidising fossil fuels classified as “new energy”.

More broadly, there are concerns that this system still does not make it attractive enough for private entities to invest in renewables, with insufficient subsidies for solar and wind while coal is still being incentivised (see section below).

Another issue with the current Korean system concerns the electricity grid, with renewable energy facilities facing delays in being connected due to inadequate substations.

The government-owned KEPCO controls the grid and has a monopoly on electricity generation. The International Energy Agency (IEA) has identified restructuring of KEPCO as a key recommendation for energy reform.

There are also concerns in South Korea that expanding renewable capacity only benefits foreign companies that already dominate these markets. Earlier this year, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy issued a press release reassuring people that reports of Chinese companies dominating the Korean solar market were “not true”.

Despite all these issues, the SFOC has identified the “biggest problem” facing renewable expansion as conflicts arising with local communities, when trying to construct new renewable facilities in their vicinity.

Conservatives politicians and news outlets, often with a pro-nuclear slant, have been blamed for “tarnishing” the reputation of renewables by stating that solar projects in particular are the cause of “environmental destruction”. According to SFOC:

“As a result, there is an increasing number of local governments autonomously establishing ordinances and rules restricting the sites for solar PV and wind power.”

Nuclear

Around a quarter of South Korea’s electricity comes from its 24 nuclear reactors, placing it “among the world’s most prominent nuclear energy countries”, according to the World Nuclear Association. Its nuclear power output is the fifth largest in the world.

A desire to reduce dependence on imported fossil fuels was the primary motivation behind South Korea’s nuclear development, which began in the 1960s.

Former President Lee promoted nuclear energy and the export of South Korean reactor technology to other countries as part of his clean-energy strategy.

However, the nation has been shaken by two events that have, ultimately, left the future of South Korea’s nuclear energy looking highly uncertain.

First came the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011. Most reactors in South Korea are located close together, often near major population centres, and the accident in neighbouring Japan galvanised anti-nuclear movements across the country who feared a similar event closer to home.

The impact of the disaster on South Korea is reflected in the country’s NDC, which states:

“Given the decreased level of public acceptance following the Fukushima accident, there are now limits to the extent that Korea can make use of nuclear energy, one of the major mitigation measures available to it.”

Next, the industry was hit by a major scandal in which 100 people were indicted for corruption after fake safety certificates were issued at nuclear facilities.

This “mafia-style behaviour”, as one government official put it, led to several reactors being shut down so that cabling could be replaced after it emerged it had received certification through the corrupt operation.

The culmination of this was President Moon and his Democratic Party coming to power in 2017 with a pledge to phase out nuclear energy in South Korea.

While new reactors are still being constructed, Moon said they would not extend the operation of ageing reactors which will be decommissioned in the 2020s and 2030s. This is in line with “deliberative polling” conducted by the government to give a sense of the Korean population’s views on nuclear energy.

The government’s most recent power strategy envisions nuclear’s capacity falling only slightly from 22.5GW to 20.4GW over the next decade, with five new reactors entering operation and 11 old reactors being retired.

Nevertheless, more polling by the Korean Nuclear Society has suggested that the majority of South Koreans support the continued use of nuclear power and the opposition United Future Party is running on a pro-nuclear platform in the election.

South Korea’s significant nuclear lobby has been pushing the message that the government’s shift from nuclear to renewables could leave the country experiencing blackouts or consumers with large electricity bills. As it stands, Korean households have some of the lowest electricity prices in the OECD.

Scrutiny of the government’s anti-nuclear strategy increased in 2018 when electricity demand increased unexpectedly during a heatwave, exceeding the government’s predictions for peak demand.

Coal

Coal, which supplies 44% of South Korea’s power generation, has been under increased scrutiny due to its ties with the severe air pollution that afflicts much of the nation.

The association with this harmful “fine dust” means coal is not a partisan issue as it is in, say, the US and neither of the major political parties exhibits an enthusiastic pro-coal stance.

Nevertheless, coal has been used to provide a cheap and reliable source of energy for South Korea’s economic expansion, with efforts to decrease reliance on it lacking until relatively recently. The nation is the fourth largest importer of coal in the world.

Now, with public opinion of the fossil fuel falling and the attention of campaigners turning from nuclear to coal, there is mounting pressure to switch to cleaner energy sources.

Under these conditions, the government’s 8th Basic Plan for Electricity Supply and Demand (pdf) in 2017 suspended plans for any new coal-fired power stations not already under construction, and pledged to close older existing plants “ahead of the end of their design lifetime”. The country’s coal plants are, however, relatively young, averaging 15 years old.

Besides cutting greenhouse gas emissions, the government’s plan states its policies will cut the amount of polluting fine dust produced by power generation by 62% from 2017-2030.

Following this central government plan the province of South Chungcheong, home to half of the nation’s coal capacity, joined the Powering Past Coal Alliance at the end of 2018, with the aim of shutting down 14 coal power plants by 2026. However, the power to close these facilities ultimately rests with the central government.

(The province currently has 31 coal units in operation and one more is being built. The oldest 14 units in South Chungcheong total 7GW and a similar capacity of new plants is under construction across the country.)

In November 2019, the government committed to shutting six coal-fired plants by 2021, a year earlier than previously pledged and in addition to the four already closed since 2017.

However, as the plants due to be closed are old and also smaller than newer facilities, overall capacity is expected to remain high, increasing from 36.8GW to 39.9GW between 2017 and 2030. Seven new coal units are set to come online over the next few years.

Furthermore, the government’s latest energy master plan released last year suggested the government could continue giving permits to new coal plants and there is still no plan for a complete phaseout.

South Korea’s support for coal is not confined to its own shores. A report by Greenpeace identifies the nation as the third-biggest public investor in overseas coal-fired power plants in the G20 group of major economies, after China and Japan.

Among the main countries targeted for investment are Bangladesh, Indonesia and Vietnam, all of which have laws allowing air pollution levels that would be illegal in South Korea.

Analysis by SFOC found that South Korean public financial institutions have provided around $17bn (£13.7bn) of financial support for coal-power projects since 2008, around half of which was for schemes overseas.

The group concludes that without this “easily available financing…such proliferation of coal-fired power plants would not have been possible”.

Another report by Carbon Tracker questions the economic viability of South Korean coal power, identifying the country as having “the highest stranded asset risk in the world” due to market structures which effectively guarantee high returns for coal.

It concludes that South Korea “risks losing the low-carbon technology race” by remaining committed to coal. A newer report from the thinktank says it is already cheaper to invest in new renewables than build new coal in South Korea and it will be cheaper to invest in new renewables than to operate existing coal in 2022.

A recent state bailout for power equipment manufacturer Doosan Heavy Industries & Construction, ostensibly in response to the coronavirus pandemic, has been criticised by environmental groups who warn it must not be used as an opportunity to support unviable fossil fuel investments. In a statement, Greenpeace said:

“Doosan Heavy’s crisis did not stem from coronavirus…We hope that financially stable companies are not losing opportunities to overcome the coronavirus crisis because of the state financing to Doosan Heavy.”

While coal is the dominant fossil fuel used in South Korea, the country is also the third largest importer of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in the world.

South Korea also has a large oil refining sector to deal with the crude oil it imports. It does not have any international pipelines so relies on tanker shipments for both oil and LNG.

Under the government’s plans, LNG use is forecast to grow steadily over the coming decade as electricity generation from coal and nuclear declines. It plans to see natural gas accounting for 19% of the total power generation mix by 2030, up from 17% in 2017.

However, recent global events have once again led to a significant recent shift in South Korean energy, with low oil prices contributing to an estimated 25% increase in the nation’s gas imports this quarter, compared to last year.

This in turn has been linked to a drop in coal imports, spurred by tighter air pollution measures, coal plant shutdowns and the economic impact of coronavirus.

Transport

South Korea is one of the world’s most important automotive manufacturers, the seventh largest car exporter and home to major companies such as Hyundai and Kia. Lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles have also emerged as one of the nation’s biggest exports.

Domestically, the number of cars on the road has been increasing, but there have been efforts by authorities to encourage a switch to cleaner transport.

As with the anti-coal action seen in South Korea, this has partly been driven by the “social disaster” of air pollution, which has even seen Seoul ban the most polluting diesel cars in the city centre.

The sale of electric vehicles has been encouraged through subsidies and tax rebates, and the overall number on the road doubled in 2018 to 33,000, according to the IEA. This inched up slightly last year, although they still only account for around 2% of new sales.

There are also plans to scale up overseas sales of cleaner vehicles, with an official target of increasing production capacity of zero-emissions vehicles from 1.5% of output to more than 10% by 2022.

The government has announced that by 2030 a third of all new cars being sold in South Korea should either be electric or running on hydrogen. It has also announced its intention to secure 10% of the global market for electric cars by that date.

Alongside this announcement came a pledge of 60tn won (£40bn) for future car technologies over the next 10 years, including green developments, with a third of that going to the Hyundai Group alone.

In the past, South Korean car manufacturers have drawn criticism for failing to invest sufficiently in more fuel-efficient or cleaner vehicles.

The government also intends to encourage bus and truck operators to switch to cleaner vehicles. It has said it will increase the number of charging points from around 5,000 to 15,000 locations by 2030.

However, there had been no announcement yet for plans to completely phase out diesel and petrol vehicles, as other nations have pledged.

Industry

Modern South Korea has been built on energy-intensive industries including steel, shipbuilding and automotives, many of which are difficult to decarbonise.

As a result, its energy consumption per capita is nearly double the global average. In most developed countries, this figure has been decreasing over time as energy efficiency improves and economies shift away from industry towards the services sector.

However, according to CAT, the opposite trend is expected in South Korea as industrial energy use increases and population declines. The nation’s NDC says that this is a significant burden when it come to cutting South Korean emissions:

“Korea’s mitigation potential is limited due to its industrial structure with a large share of manufacturing (32% as of 2012) and the high energy efficiency of major industries.”

The key tool for cutting Korean industrial emissions is its emissions trading scheme (ETS), a cap-and-trade system which was introduced in 2015 and became the second largest in scale after the EU ETS.

In total, the nation’s ETS covers more than 500 heavy polluters, including the steel, cement, refinery, aviation and power sectors, which are estimated to produce around two-thirds of the country’s emissions.

However, compared to the EU ETS, the South Korean system gives away far more emissions “allowances” to the participating companies for free, meaning they can pollute without spending money.

Other large emitters are covered by a broader scheme known as the target management system. There are no policies that require new industrial installations to be low carbon.

In the net-zero plan currently being floated by the Democratic Party there have been discussions of introducing a carbon tax, an idea that has been discussed in South Korean politics for several years. Details of the extent of this carbon tax have not been made clear.

Impacts and adaptation

While the smog of air pollution is the most visible result of South Korea’s high-polluting economy, there is evidence that the wider impacts of global warming are already playing out across the Korean peninsula as well.

The average temperature in South Korea has already increased by around 1.4 and this is bringing change to a nation that normally has four well-defined seasons.

Analysis has shown that since the early 20th century summers across the country have become longer, rising from 80-110 days in the decade starting in 1910 to 110-149 days in the 2010s.

Extreme events over the past couple of years have brought global warming to the fore, notably the unprecedented heatwave that struck the entire country in the summer of 2018.

Temperatures in Seoul reached 39.6C, the highest value ever recorded in more than a century of observations, with dozens of deaths attributed to the rising temperatures.

A study conducted in the aftermath of the event concluded that “statistically extremely rare events like that of summer 2018 will become increasingly normal if global average temperature is allowed to increase by 3C”.

Moreover, the study noted that the event appeared to have raised public awareness of the risks associated with global climate change. Other attribution studies have identified links between anthropogenic climate change and extreme temperatures or early seasonal shifts.

Firefighters battle a blaze in Goseong, South Korea on 5 April 2019. Credit: Xinhua / Alamy Stock Photo.

With much of South Korea’s population living in coastal regions, some research has examined the impact that increased storm surges linked to climate change could have in the coming decades.

One paper concluded that the intensity of typhoons striking South Korea and the surrounding region has increased by 50% over the past 40 years, due to rising sea temperatures.

South Korea is also vulnerable to wildfires. Last year it was struck by one of the largest on record, in Goseong county. While studies have attributed other recent blazes around the world to climate change, the same research has not been undertaken for South Korea’s fires.

In 2008, the government published its national climate change adaptation master plan covering the years 2009-2030.

Among the key vulnerable areas identified were damage to infrastructure due to increased rainfall, rising costs of natural disasters and threats to public health resulting from infectious disease spread and heatwaves.

Note on infographic

Data for energy consumption comes from BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019.

Data for greenhouse gas emissions by sector is a combination of two datasets compiled by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and EDGAR.

Values for methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O) and fluorinated gases cover all sectors, including LULUCF, and come from the PIK primap database v2.0. Values for GHG emissions from LULUCF also come from the PIK primap database, however these are only available to 2015, from the earlier v1.2 of the database. Note that LULUCF data for 2015 is an extrapolation made by PIK from previous years.

The remaining values come from the EDGAR CO2 emissions database, downloaded from the website OpenClimateData. The EDGAR categories described in full are as follows: Buildings (non-industrial stationary combustion: includes residential and commercial combustion activities); Transport (mobile combustion: road and rail and ship and aviation); Non-combustion (industrial process emissions a1nd agriculture and waste); Industry (industrial combustion outside power and heat generation, including combustion for industrial manufacturing and fuel production); Power & heat (power and heat generation plants).

Combining GHG emissions in 2015 (bar LULUCF) from PIK primap database 2.0 database and LULUCF emissions in 2015 from PIK database v1.2 also shows South Korea has the world’s 13th largest greenhouse gas emissions, including LULUCF, in 2015.

Per capita emissions in 2015 come from combining the above 2015 figure for GHG emissions and South Korea’s population in 2015 from the World Bank.

South Korea’s pledge to reduce its emissions by 37% by 2030 relative to business-as-usual, come from its INDC submitted to the UN in 2015.

-

The Carbon Brief Profile: South Korea

-

Everything you need to know about South Korea's climate and energy policy