As part of its series on how key emitters are responding to climate change, Carbon Brief looks at whether Nigeria is likely to move past its economic reliance on oil and how it intends to supply power to its rapidly booming population.

Nigeria has the largest economy and population of any country in Africa. It is expected to overtake China to become the world’s second most populous country after India by the end of the century.

It was the world’s 25th biggest emitter of greenhouse gases in 2019, the second highest in Africa after South Africa.

The country’s economy is closely tied to oil and gas exports. Profits from fossil fuels currently account for 93% of Nigeria’s total export revenue. The production of oil and gas in Nigeria has also been linked to steep societal inequalities and environmental disasters.

Nigeria has one of the highest rates of energy poverty in the world and suffers from chronic power cuts. In the run up to the 2023 general election, the Nigerian government reversed a pledge to end fuel subsidies amid the threat of protests.

A recent analysis of Nigeria’s energy potential found the country could meet 59% of its energy consumption needs with renewables by 2050 – largely solar power.

However, national pundits are still advocating for Nigeria to close its electricity gap through the use of more fossil fuels, including the country’s largely untapped coal reserves.

Nigeria is already suffering loss and damage from climate change. Sharp increases in extreme heat are affecting the many millions of people without access to air conditioning or electricity and changes to precipitation threaten Nigeria’s largely rain-fed agricultural sector. In 2022, Nigeria faced deadly floods made 80 times more likely by human-caused climate change.

Nigeria announced that it will aim to reach net-zero emissions by 2060 at the COP26 climate summit in 2021. The government has also pledged to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 20% by 2030, when compared to “business-as-usual” levels. This pledge rises to 47% on the condition of international support.

- Politics

- Paris pledge

- Oil and gas

- Coal

- Deforestation, wood burning and agriculture

- Renewables and ‘green growth’

- Climate finance

- Impacts and adaptation

Politics

More than 220 million people live in Nigeria, making it Africa’s most populous nation. It is made up of 36 states and has a multi-ethnic and culturally diverse society, with more than 250 ethnic groups.

Nigeria’s population is growing fast. It is expected to become the world’s third most populous country by 2050 – and the second largest by the end of the century. At present, more than half its population are under 18.

Lagos, the former capital, is the largest city in Africa. Between 2010 and 2030, it is estimated that 77 people will move to Lagos every hour – making it one of the fastest growing cities in the world.

Nigeria is a country of steep inequalities. It is home to some of Africa’s richest people, including the continent’s richest man Aliko Dangote, chief executive of Dangote Cement – Africa’s largest cement producer, and billionaire Mike Adenuga, a telecommunications and oil tycoon. However, two-thirds of the total population live below the poverty line.

It is a major cultural influencer. Nigeria has the world’s second largest film industry, commonly known as “Nollywood”. Many Nigerian musicians are successful worldwide.

Muhammadu Buhari was reelected Nigeria’s president in the country’s 2019 elections after first gaining power in 2015. His 2015 win marked the first time that a sitting president had been defeated in Nigeria. At the time, the BBC’s Nigeria correspondent Will Ross said the result was “a sign that democracy is deepening” in the country. (Prior elections had been marred by allegations of fraud.)

Buhari’s campaign was centred around promises to crack down on terrorism and corruption. Corruption has been described as “ubiquitous” in Nigerian society and “rife” in its oil, power and environmental sectors. Buhari has taken steps to address corruption since 2015, but progress has been slow. The country is faced with ongoing terrorism threats from Boko Haram, a jihadist group based in the northeast of the country.

Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari, Abuja Nigeria. Credit: Rey T. Byhre / Alamy Stock Photo.

Buhari also pledged to boost Nigeria’s economy. Though it is the largest economy in Africa, it is heavily dependent on oil exports and so vulnerable to changing oil prices. In 2020, the country fell into recession following an oil price plunge driven by the global response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Nigeria held a general election on 25 February 2023. Buhari was not able to seek reelection for a third term.

The three frontrunners for president were Bola Tinubu from the governing All Progressives Congress, Atiku Abubakar from the People’s Democratic Party and Peter Obi from the Labour Party. All three have faced allegations of wrongdoing, including trading in narcotics, money laundering and global tax avoidance, according to BBC News.

Obi was favourite to win – but Nigerian election polls are known to be unreliable.

Both Obi and Abubakar tweeted that climate change is “real” in the wake of deadly flooding in Nigeria in 2022.

However, all the presidential candidates faced criticism from Nigerian environmental campaigners for failing to focus on new measures to meaningfully address climate change with their election bids, according to the publication Earth Beat.

In January 2023, Climate Home News reported that “the country’s leading presidential candidates have so far failed to take the issue [of climate change] seriously on the campaign trail”, adding that “in spite of the extreme floods” in 2022, “climate change was still not a decisive issue in the country’s elections”.

The publication added:

“The leading candidate in the latest polls, Peter Obi, has dismissed the importance of addressing the climate crisis, while the second place, Bola Tinubu, has supported coal expansion.”

However, China Dialogue reported that Obi did make numerous climate promises in his manifesto, including a pledge to shift Nigeria from “fossil fuel dependency to climate and eco-friendly energy use”.

On 1 March, Tinubu was declared the winner of the presidential election, which was marred by allegations of voter fraud and intimidation.

Despite being Africa’s largest oil producer, Nigeria is in the midst of a long-term energy crisis. Almost one in three people in Nigeria do not have access to electricity – and in 2018, the typical Nigerian firm experienced more than 32 power cuts. Constant power cuts have led to a heavy reliance on back-up generators across the country.

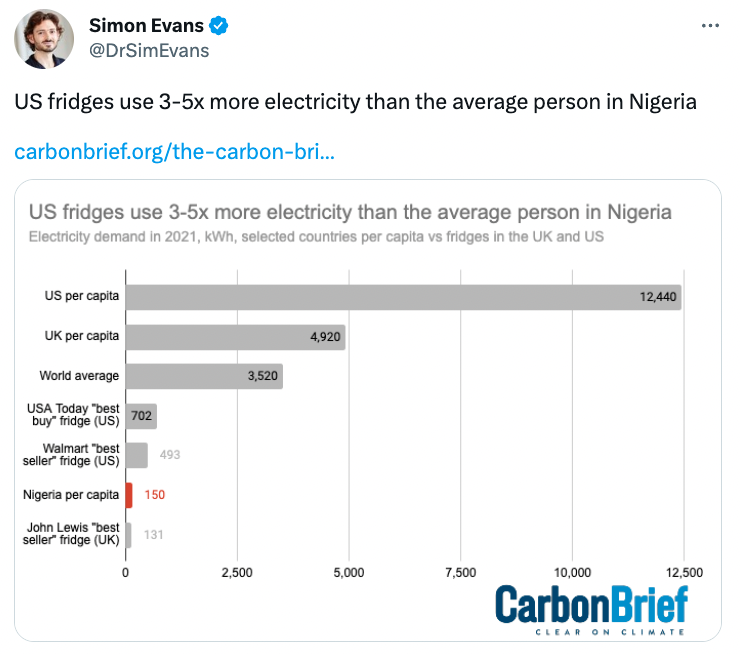

Lack of access to electricity in Nigeria means that the average person uses very little power. For example, Carbon Brief analysis shows popular American fridges (493–702kWh/year) use three to five times more electricity every year than per capita demand in Nigeria (150kWh/year), which includes industrial and commercial uses.

According to a survey conducted in 2015, more than half (61%) of Nigeria’s population consider climate change to be a “very serious problem”. (This compares to a global average of 54%.) Nigerians consider “extreme heat” to be the largest of climate change’s threats, the survey says.

Nigeria is one of a number of African countries with a growing youth climate movement. In 2022, climate activist Adenike Oladosu told Carbon Brief that Nigeria is on “the frontline of the loss and damage” from climate change.

The threat of climate change on our #democracy is already a reality. This could be one of the single greatest impacts on elections in Nigeria.

— Adenike Titilope Oladosu (@the_ecofeminist) January 10, 2023

We are yet to recover from the 2022 unprecedented flood. Hence, the need for climate justice.#NigeriaDecides2023#ClimateAction pic.twitter.com/JXyJ26wlX5

Paris pledge

Nigeria is part of three negotiating blocs at international climate talks. These include the G77 and China; the African group and the Coalition for Rainforest Nations. It is also a member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) – an organisation formed in the 1960s by various oil-rich states with the mission to “coordinate and unify the petroleum policies” of its members.

(More information on each group is available in an in-depth explainer of negotiating blocs by Carbon Brief.)

The country’s annual greenhouse gas emissions were 345.7m tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) in 2018, according to the CAIT database maintained by the World Resources Institute (WRI), which includes emissions from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF).

Its per capita emissions in 2018 were around 1.8 tonnes of CO2e, far below the global average of 7 tonnes and also lower than in India (2.7 tonnes), Mexico (5.5 tonnes) and Indonesia (9.2).

Nigeria is signed up to the Paris Agreement, the international deal aimed at tackling climate change. It ratified the agreement in 2017.

In its first climate plan submitted under the Paris Agreement in 2017 – also known as a “nationally determined contribution” (NDC) – Nigeria pledged to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 20% by 2030, when compared to “business-as-usual” (BAU) levels. The pledge rose to 45% on the condition of international support.

In 2021, Nigeria updated its NDC. Through this, it recommitted to slashing emissions 20% below BAU by 2030, rising to 47% on the condition of international support. The independent research group Climate Action Tracker (CAT) rates Nigeria’s 2030 unconditional target as “1.5C compatible”, when considering each country’s “fair share” towards tackling climate change.

(For more information on international support, see: Climate finance.)

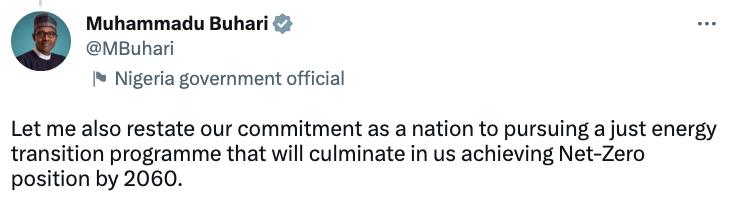

Former president Buhari announced that Nigeria will aim to reach net-zero emissions by 2060 at the COP26 climate summit in 2021.

In the same year, Nigeria passed a landmark Climate Change Act, recommitting the government to the Paris Agreement’s goals of limiting global warming to below 2C, with the aim of keeping temperatures at 1.5C.

The Act also mandates the ministry of environment to set carbon budgets and to release national climate action plans every five years. (It is based on the UK’s 2008 Climate Change Act.)

Also in 2021, Nigeria submitted its “long-term vision” for 2050 under the Paris Agreement. This plan said Nigeria would reduce its emissions by half by 2050, when compared to “current” levels.

In August 2022, Buhari released an energy transition plan laying out a vision for how Nigeria can reach its net-zero target.

It estimates that implementing Nigeria’s transition to net-zero will cost $1.9tn – or around $10bn annually over “the coming decades”. Ahead of COP27 in November 2022, Nigeria sought to raise $10bn from “financers and donors” to “kick start” the journey to net-zero. Nigeria has also said its plan represents a $23bn investment opportunity.

(It comes after countries including South Africa and Indonesia have agreed “just energy transition partnership” deals with developed nations.)

The plan says Nigeria will cut emissions in its power sector by moving away from a reliance on diesel and petrol generators (see: Oil and gas), pursuing an “initial expansion of gas” and “integrating renewables”. It plans to eliminate emissions from other sectors such as cooking and transport through “renewables-backed electrification”.

Through this plan, Nigeria aims to lift 100 million people out of poverty. It estimates that the measures outlined will create a net 340,000 jobs by 2030 and 840,000 by 2060.

Several independent research groups have been critical of the plan’s reliance on gas in the short term. An analysis by CAT said that further gas expansion in Nigeria would not be in line with the 1.5C goal and estimated that, over the next decade, Nigeria could create 2.5 times more jobs by focusing on renewable expansion rather than gas.

Oil and gas

Oil was first discovered in Nigeria in Oloibiri, part of the Bayelsa State, in 1956.

Since then, Nigeria grew to be Africa’s largest oil producer – although it was overtaken by Angola in 2022. It is a member of OPEC – an organisation representing the interests of oil-rich nations.

It produced an average of 1.98m barrels of crude oil a day between 1973 and 2022 – reaching an all-time high of 2.48m barrels per day in 2010. In 2021, it produced around 1.63m barrels of crude oil a day, making it the 15th largest producer globally.

The vast majority of Nigeria’s oil is exported. In 2020, the largest recipients of Nigerian oil were India, Spain and South Africa.

Oil and gas currently accounts for 93% of Nigeria’s total export revenue. Fossil fuel exports collectively provide around 70% of the government’s revenue.

Nigeria has an estimated 37bn barrels of untapped crude oil reserves. According to the IEA, it contains 15% of Africa’s oil reserves and 16% of its gas.

However, its heavy economic reliance on oil leaves Nigeria vulnerable to changing prices. In 2020, the country fell into recession following an oil price plunge driven by the global response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

During the price plunge, Nigeria significantly cut its oil output in accordance with a deal made by OPEC and “allied” nations.

In 2021, a new Petroleum Industry Act was signed into law, creating new incentives for companies to explore for oil.

In 2022, Nigeria’s oil production fell by 40%, when compared to pre-pandemic levels in 2019. Market Watch reported that the fall “was attributed to technical problems, insecurity, rising production costs, theft and lack of payment discipline in joint ventures”.

Oil and gas production in Nigeria faces ongoing threats from corruption, terrorism and theft from criminal organisations that steal crude directly from pipelines, before exporting it on black markets. A report found Nigeria lost $41.9bn from oil theft during 2009-18. Reuters reported that a further $2bn was lost to theft in 2022.

In its post-pandemic recovery plan released in 2020, Nigeria pledged to scrap fuel subsidies, which are mostly spent on keeping petrol and diesel cheaper. According to Bloomberg, the decision could have saved the government “at least $2bn” a year.

However, the government reversed the decision in January 2022 over fears it could drive protests in the run up to the 2023 presidential election, Reuters reported. It added that the amount spent on fuel subsidies reached $5.6bn in the first eight months of 2022.

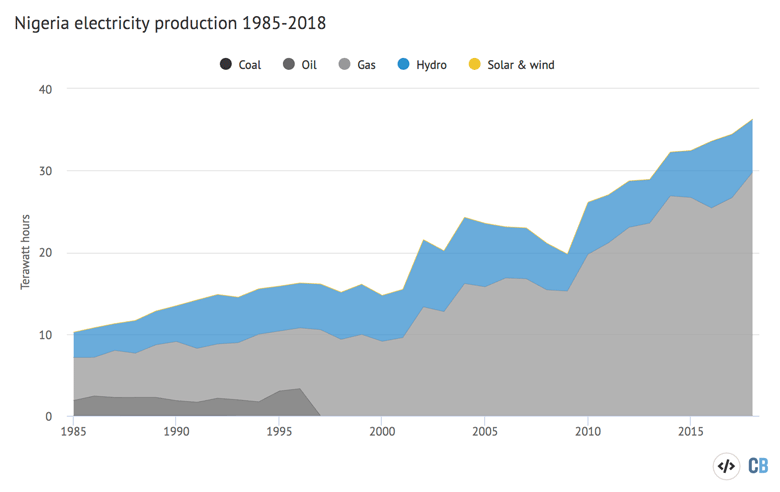

Nigeria sources the majority of its domestic electricity supply from gas. The chart below shows Nigeria’s electricity generation from 1985-2018.

(The country’s total electricity generation is relatively low for its population – almost one in three people lack access to electricity in Nigeria. The chart does not include the contribution from oil-powered back-up generators, which are relied on across the country during power cuts.)

Nigeria has signalled that it intends to plug its electricity gap by using more gas. In 2021, Buhari declared he was starting the “decade of gas”, with the aim of achieving a “gas-powered economy” by 2030.

Expanding gas power by 2030 is a key part of Nigeria’s energy transition plan, its blueprint for reaching net-zero by 2060.

Many have been critical of Nigeria’s focus on boosting gas power.

Independent assessments agree that there can be no new oil and gas expansion globally if the world is to meet its aspiration of keeping global temperatures at 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

In its assessment of Nigeria, Climate Action Tracker warned the focus on gas could lock the country into “emissions-intensive infrastructure that will likely lead to the major stranding of assets and misallocation of investment resources”.

A recent analysis by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) found that Nigeria could provide electricity access to all its people five years faster under a scenario of fast renewable power expansion, when compared to its current plans.

The production of oil and gas in Nigeria by multinational companies has had severe social and environmental impacts.

The Niger Delta, the end point of the river Niger in southern Nigeria, is a hot spot for oil spills. The region saw more than 12,000 oil spill incidents from 1974-2014. It is estimated that, during that time, 40m litres of crude oil spilled into the Niger Delta each year.

According to Nigeria’s National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA), there have been more than 1,000 oil spill incidents country-wide since January 2021.

An investigation by Amnesty International found the Anglo-Dutch oil company Shell and the Italian oil company Eni were responsible for most of the spills in the Niger Delta from 2011-17.

Theft and sabotage played a role in 75% of oil spills in Nigeria since 2016, according to Africa’s Institute for Security Studies.

In 2011, a United Nations report focusing on Ogoniland – the most affected region in the Niger Delta, found that it would take 30 years and $1bn to clean up the spills. It found public health in the region was “severely threatened” due to the contamination of water supplies.

A study published in 2019 found oil spills in the Niger Delta were associated with a doubling of the death rate for newborn children in the region. The findings are “consistent with medical and epidemiological evidence showing that exposure to hydrocarbons can pose risks to fetal development”, according to the study authors.

Nigeria’s International Centre for Investigative Reporting has produced numerous detailed reports into how oil spills continue to affect the lives of those living in the Niger Delta.

In 2023, 14,000 people from the Niger Delta launched a legal case against Shell, seeking compensation for the impact of oil spills on their lives and livelihoods.

The production of gas has also caused environmental disasters. In 2020, DeSmog UK reported on how the oil company Total South Africa broke its promise to build a hospital in the Niger Delta after a gas pipeline explosion in 2012.

Oil and gas production is also a major driver of CO2 and methane emissions in Nigeria (see infographic).

This is largely due to “gas venting”, the practice of releasing the gas that surfaces during oil production, and “gas flaring”, the practice of burning off surfaced gas.

Gas is less valuable than oil and so is often discarded through venting or flaring. However, gas venting produces high amounts of methane – a greenhouse gas that is around 27-30 times more powerful than CO2 over a 100-year period. Burning off gas through flaring decreases the amount of methane released, but inefficient flaring still causes substantial methane emissions.

(Gas flares also threaten human health, contaminate water supplies and affect crop production in Nigeria, Deutsche Welle reported.)

An estimated 6.6bn cubic metres of gas was flared in Nigeria in 2021 – making it the world’s seventh largest gas flarer. This wasted gas was equivalent to 14% of the country’s output.

In its first national climate pledge, the Nigerian government promised to “work towards” ending gas flaring by 2030. To aid this goal, the government has established a Gas Flare Commercialisation Programme to encourage investment in practices that reduce gas flaring.

From 2000 to 2019, the amount of gas flaring fell by 70%, according to satellite data from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

However, Nigeria previously pledged to end gas flaring by 2020 under its National Gas Policy – a target it did not come close to meeting.

Coal

Nigeria has an estimated 2bn metric tonnes of coal reserves. However, it has only ever had a handful of small coal-fired power plants in operation.

The mining ministry has repeatedly said it is the government’s intention to supply 30% of the country’s power with coal. And some commentators see coal as a solution to Nigeria’s energy crisis, including 2023 presidential candidate Bola Tinubu.

There were plans for a 1,200 megawatt (MW) coal-fired power plant in Kogi, a coal-rich state in central Nigeria. However, the project has been repeatedly shelved due to financing issues. In 2011, the government announced that it intended to build two more coal plants, but plans for these have not yet emerged, more than a decade later.

By 2019, the government had handed out 36 coal mining licences supposedly tied to electricity generation capacity of 10,000MW, according to an investigation by Nigerian newspaper the Daily Trust. However, the paper found that none of these power projects have come to fruition.

Despite a lack of action, the IEA said in its 2019 Africa Energy Outlook that it expected Nigeria to source a substantial amount of its electricity from coal by 2030. (This was based on Nigeria’s stated policies, which so far have sparked little implementation.)

In its 2022 Africa Energy Outlook, the IEA noted there are unlikely to be any new coal-fired power stations in sub-Saharan Africa beyond those already under construction, following China’s pledge to end coal power financing abroad.

Coal is currently mined for the purpose of powering industries, particularly the cement industry (pdf). According to Global Energy Monitor, there are three small coal-power plants at cement production sites still in operation in Nigeria, accounting for 285MW.

Coal mining by cement companies such as Dangote Cement has been linked to severe environmental and social impacts, including air and water pollution.

A 2019 investigation by Nigeria’s International Centre for Investigative Reporting found that, in addition to its state-approved mining activities, Dangote Cement had been illegally mining coal in Kogi for six years.

Deforestation, wood burning and agriculture

Nearly one in three people in Nigeria lack access to electricity. Instead, many rely on the burning of wood, “biogas” – a gas produced from animal and plant waste, and other types of waste in order to generate energy in the home.

This is particularly true for food preparation. In Nigeria, less than a quarter of people have access to “clean cooking” and the rest – mostly women – rely on polluting and inefficient cookstoves, says the IEA.

As a result, biomass and waste makes up the majority of Nigeria’s energy supply (see infographic).

The burning of biomass at home drives harmful indoor air pollution. In 2018, Nigeria was responsible for a third of Africa’s total fine particulate matter (PM2.5) emissions – largely as a result of household biomass burning.

Across sub-Saharan Africa, the household pollution resulting from a reliance on biomass was directly linked to 500,000 premature deaths in 2018, according to the IEA.

A reliance on wood for fuel is also a major driver of deforestation in Nigeria – and improving access to clean cooking has been flagged as a key option for reducing emissions in the country. (Other drivers include the conversion of forest to agricultural land and logging for timber production.)

Rainforest in Nigeria. Credit: INTERFOTO / Alamy Stock Photo.

Nigeria has a tropical climate and is home to dense rainforest that supports more than 1,000 species of birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians. Species only found in Nigeria include the Ibadan malimbe, the Sclater’s monkey and the Niger Delta red colobus.

However, much of Nigeria’s tropical forest has already been destroyed. Between 2000 and 2005, the country lost 55.7% of its primary forest – giving it the highest deforestation rate in the world over that period.

Since 2005, rates of deforestation have remained high in natural forests, according to data from the Global Forest Watch. From 2010 to 2019, Nigeria lost 86,700 hectares of tropical forest, releasing the equivalent of 19.6MtCO2.

In 2022, Mongabay reported that poverty – exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic and its impact on oil prices (a major government revenue generator in Nigeria, see: Oil and gas) – was a major driver of escalating deforestation in some of the country’s most biodiverse areas.

In 2006, Nigeria’s federal government introduced a National Forest Policy in an attempt to curb deforestation, which was ratified by all states. However, enforcement of the policy was weak (pdf) and it had little impact on deforestation figures.

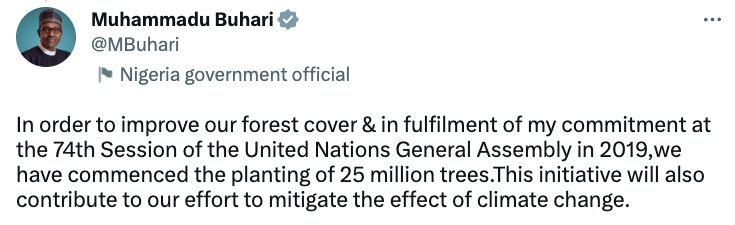

In 2019, president Munhammudu Buhari committed to “mobilise Nigerian youths towards planting 25 million trees to enhance Nigeria’s carbon sink” at a UN climate summit in New York.

In 2020, the federal government approved a new National Forest Policy aimed at “protecting ecosystems” while enhancing social development.

Nigeria has also committed to restoring 4m hectares of forest under the Bonn Challenge, a global tropical forest restoration project spearheaded by the government of Germany and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Around 78% of Nigeria’s land is used for agriculture and the sector provides a primary source of income for 70% of Nigeria’s population.

The sector was responsible for a quarter of the country’s total emissions in 2017, largely as a result of the rearing of animals including cattle, sheep and goats. (The belching and manure from ruminant animals causes the release of methane.)

In its first climate pledge, Nigeria said it would reduce its overall emissions through “climate smart agriculture” – which it said would simultaneously slash emissions while meeting the challenges posed to farming by climate change (see: Impacts and adaptation).

Proposed “climate smart” policies included encouraging the planting of more native vegetation and putting a stop to “slash and burn” agriculture.

Such agricultural practices could offset 74m tonnes of greenhouse gases every year by 2030, according to Nigeria’s climate pledge.

The government’s Agriculture Promotion Policy for 2016-2020 repeats the commitment to promote “climate smart agriculture”.

Renewables and ‘green growth’

Nigeria currently sources very little of its energy from wind and solar.

In 2018, around 18% of its electricity came from hydropower – the largest source of low-carbon energy in Nigeria’s power mix (see highchart above).

Notable hydropower projects in Nigeria include the proposed 3,000MW Mambilla Dam, which has been planned since 2003 but has been plagued with controversies that have stopped it from being built.

In 2006, Nigeria produced a “Renewable Energy Master Plan” (REMP). Updated in 2011, the plan seeks to increase the supply of renewable electricity to 23% of the total electricity generation in 2025 and 36% by 2030.

In its national climate plan outlined in 2017, Nigeria pledged that it would “work towards” installing 13,000MW of solar power by 2030. It marked this as one of the “key measures” needed to tackle the country’s carbon footprint.

And in its Covid-19 recovery plan released in 2020, Nigeria laid out a new framework for boosting solar power. It aims to bring solar power to 5m households by 2023. The project is aimed at “rural communities that have little or no access to the national grid” and will create 250,000 jobs, says the government.

If completed, the project would mark a shift towards “decentralised energy” in Nigeria. (Decentralised energy is generated off the main grid and produced close to where it will be used rather than at a large central plant.)

Several reports have found that such community-based renewable energy schemes could be the cheapest and most efficient way for Nigeria to address its large electricity gap, particularly in rural areas.

Renewable power development in Nigeria was also given a boost by the passing of a landmark Climate Change Act in 2021, which commits public and private bodies within the country to strive to reach net-zero emissions by 2060.

However, despite these commitments, there has been little progress on the development of solar power in Nigeria. Analysts say that Nigeria “has abundant sources of renewable energy but lacks the adequate government backing to harness these resources for electricity power”.

And in its energy transition plan released in 2022, the Nigerian government made it clear that it sees expanding gas power as a priority until 2030, although it promises that renewables will be “integrated”.

Several have criticised the plan’s reliance on gas in the short term. An analysis by Climate Action Tracker estimated that, over the next decade, Nigeria could create 2.5 times more jobs by focusing on renewable expansion rather than gas.

And a recent analysis by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) found that, with short-term policies aimed at boosting clean power, Nigeria could meet 59% of its energy consumption needs with renewables by 2050 – largely solar.

Climate finance

Nigeria has pledged to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 20% by 2030, when compared to “business-as-usual” levels. This pledge rises to 47% on the condition of international support in terms of climate finance.

“Climate finance” refers to money – both from public and private sources – which is used to help reduce emissions and increase resilience against the negative impacts of climate change.

On a visit to the country in 2018, former UK prime minister Theresa May announced that Nigeria would be the first country to take part in the “Climate Finance Accelerator” programme, an international initiative backed by the UK government aimed at helping countries to transform their climate pledges (NDCs) into “Climate Investment Plans”.

The initiative identified 14 projects that could help Nigeria reach its climate pledge at the cost of $500m. Most of the projects involve Nigeria developing more solar power.

In an updated version of its climate pledge released in 2021, Nigeria said that reaching its conditional emissions target would require $177bn in climate finance from 2021-2030.

And in 2022, Nigeria launched an energy transition plan, its blueprint for reaching net-zero by 2060.

It estimates that implementing Nigeria’s transition to net-zero will cost $1.9tn – or around $10bn annually over “the coming decades”. Ahead of COP27 in November 2022, Nigeria sought to raise $10bn from “financers and donors” to “kick start” the journey to net-zero. Nigeria has also said its plan represents a $23bn investment opportunity.

Analysis by Carbon Brief shows that Nigeria received $1.9bn in climate finance from other countries in 2020 – making it the world’s ninth largest recipient that year.

The countries to send the most climate finance to Nigeria in 2020 were France, Japan, the US and the UK. The biggest contributor to climate finance in Nigeria overall that year was the World Bank.

Impacts and adaptation

Nigeria describes itself as a country that is “considerably impacted” by climate change.

Temperatures in Nigeria have risen by around 1.6C since the start of the industrial era – higher than the global average. Depending on the rate of future climate change, temperatures could rise by a further 1.5-5C by the end of the century.

Despite a recorded rise in average temperatures, there is currently very little research into how climate change has affected heatwaves in Nigeria. However, research does suggest that heatwaves are expected to increase in frequency in Nigeria under any amount of future warming.

The number of “hot nights” in Nigeria is also expected to rapidly increase in coming decades. “Hot nights” are those where nightime temperatures are in the top 10% experienced by a region. Hot nights are known to exacerbate respiratory and other existing health problems and have previously been linked to increased death rates.

Advances in extreme heat particularly threaten the many millions without access to electricity or air conditioning in Nigeria. In urban areas, just 92 in every 1,000 people have access to air con. In rural areas, it is just 14 in every 1,000.

Fulani elders take a rest in the shadow on a hot day near Kaduna, Nigeria. Credit: Zsolt Repasy / Alamy Stock Photo.

Nigeria has a tropical climate. The southernmost part of the country is affected by monsoon rainfall and is characterised by rainforests and mangroves, the country’s middle belt has a tropical savannah climate and the most northern part of the country is arid and hot.

Most parts of the country have seen a reduction in rainfall. The government estimates that, from 1971 to 2000, average rainfall has decreased by 2-8mm across the country.

In the south, climate change is affecting the timing, predictability and duration of monsoon rainfall. Meanwhile, Nigeria’s northern region has experienced a steep rise in the frequency and duration of drought. This in turn has driven harmful dust storms and desertification.

People riding donkeys on road in dust sandstorm, Nigeria. Credit: Eye Ubiquitous / Alamy Stock Photo.

The country’s northeastern region borders Lake Chad, which provides a water source for 20 to 30 million people across Nigeria, Niger, Chad and Cameroon. Since the 1960s, it has shrunk by 90% as a result of climate change and overextraction.

While the total amount of rainfall has decreased, individual rainstorms are becoming more intense, research shows. This has led to an increase in extreme flooding across much of the country. Nigeria has seen deadly flash floods almost every year for the past decade.

In 2022, Nigeria faced its worst floods in a decade, killing 600 people. Rapid research published in the aftermath found the flooding was made around 80 times more likely by climate change.

Across the country, changes to temperature and rainfall have greatly impacted agriculture – a sector that provides a primary source of income for 70% of Nigeria’s population.

Agriculture in Nigeria is largely rain-fed. Increases in drought and unpredictable rainfall have been linked to recent crop failures across the country – and future climate change is expected to “severely impact” Nigeria’s ability to irrigate crops. Extreme heat has also caused the death of livestock.

Some reports have suggested that increases in extreme heat, drought and the shrinking of Lake Chad could be one contributing factor to violence in northeastern Nigeria, which has forced thousands to seek safety in neighbouring Chad. (There are many other complex factors behind the violence.)

Fisherman while floating on a pumpkin that will contain fish caught with nets, Lake Chad. Credit: Universal Images Group North America LLC / DeAgostini / Alamy Stock Photo.

Globally, some research has found a correlation between climate-related disasters and outbreaks of violence. However, it is still a highly contested field of science – and other researchers have argued that there cannot be “one effect to rule them all” when it comes to what sparks a conflict.

In 2011, Nigeria released its “National Adaptation Strategy and Plan of Action on Climate Change” (pdf). This outlined policy recommendations for improving adaptation for sectors including agriculture, coastal farming, forestry and energy production.

This was followed in 2020 with the release of a framework report for its upcoming National Adaptation Plan. This framework plan aims to “clarify Nigeria’s approach” to climate adaptation after years of what some perceived to be inaction.

In the report, the country’s environment minister Dr Muhammad Mahmood Abubakar, writes:

“The phenomenon of climate change is staring everyone in the face, and actions to handle its impacts have become far more critical than before.”

The report outlines the guiding principles for Nigeria’s upcoming adaptation plan, which include involving young people, focusing adaptation around communities and ecosystems and incorporating Indigenous knowledge.

As of 2023, Nigeria’s National Adaptation Plan had still not been published.

This profile was first published on 21 August 2020 and significantly updated on 17 February 2023. On 2 March, the profile was updated again to reflect the results of the presidential election.

Note on infographic

Graphic by Tom Prater and Joe Goodman for Carbon Brief.

Data for energy consumption comes from IEA World Energy Balances 2020. Unlike previous country profile infographics, exajoules (EJ) have been used instead of millions of tonnes of oil equivalent (mtoe) as the unit of energy consumption.

Data for greenhouse gas emissions by sector is a combination of three datasets compiled by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), the Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) and CAIT.

Values for methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O) and fluorinated gases cover all sectors and come from the PIK PRIMAP database v2.2. Values for greenhouse gas emissions from LULUCF come from CAIT, although these only go as far back as 1990. This dataset has been used because PIK no longer provides LULUCF emissions data.

The remaining values come from the EDGAR CO2 emissions database. The EDGAR categories described in full are as follows: Buildings (non-industrial stationary combustion: includes residential and commercial combustion activities); Transport (mobile combustion: road and rail and ship and aviation); Non-combustion (industrial process emissions and agriculture and waste); Industry (industrial combustion outside power and heat generation, including combustion for industrial manufacturing and fuel production); Power & heat (power and heat generation plants).

The CAIT database says that Nigeria had the world’s 25th largest greenhouse gas emissions, including LULUCF, in 2018. Previous country profiles in this series have been based on PIK data, meaning the ranking is different.

Per capita emissions in 2018 come from combining the above 2018 figure for greenhouse gas emissions and the Nigerian population in 2018 from the World Bank.

Nigeria’s pledge to reduce its emissions comes from its official NDC, submitted to the UNFCCC.

-

The Carbon Brief Profile: Nigeria

-

Everything you need to know about Nigeria's climate and energy policy