In the latest article in a series on the world’s key emitters Carbon Brief looks at Mexico, a nation that is already bearing the brunt of droughts, extreme heat and hurricanes.

Mexico had the world’s 11th largest greenhouse gas emissions in 2018. It has often been touted as a climate leader among less wealthy nations, with various targets to cut emissions and develop clean power.

Oil extraction has contributed to the nation’s economic growth, although the industry’s fortunes have been declining since the early 2000s. Meanwhile, wind and solar generation have tripled over the past five years.

Under past administrations, Mexico has played an important role in global climate negotiations and was one of the first nations to introduce climate change legislation.

However, progress has ground to a halt as the current government pours money into the state-run fossil fuel sector and dismantles policies to promote renewables.

(Update 08/06/2021: The ruling party of president Andrés Manuel López Obrador held onto power but failed to win a two-thirds majority in Mexico’s midterm elections. A more decisive victory would have allowed the president to modify the constitution and roll back energy reforms introduced by his predecessor, which opened the country up to private investment in renewables.)

- Politics

- Paris pledge

- Climate policies and laws

- Wind and solar

- Hydropower and nuclear

- Oil and gas

- Coal

- Forestry and agriculture

- Impacts and adaptation

Politics

Officially known as the United Mexican States, the nation is a federal republic consisting of 31 states and the federal district of Mexico City.

It has the world’s 15th largest economy in terms of GDP and the second largest in Latin America after Brazil, as of 2019.

Mexico is generally considered to be an emerging economy. It was admitted to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) group of wealthy nations in 1994, but its economic growth and poverty reduction have both been slow since then.

The nation is often described as a climate leader among poorer countries. However, as one study puts it: “Mexico’s climate leadership consists mostly of pledges and adoption of legislation, but its actions have not yet changed its greenhouse gas emissions”.

Mexican politics has historically been dominated by the centrist Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which held power from the Mexican Revolution in 1929 to 2000, when it was toppled by the more right-wing National Action Party (PAN).

Other important parties include the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), which began as a left-wing offshoot of the PRI, and the left-wing populist National Regeneration Movement (MORENA), which was, in turn, formed by current president Andrés Manuel López Obrador when he left the PRD in 2012.

Also of note is the Ecological Green Party of Mexico, which has been criticised for its lack of focus on “green” issues and rejected by international green parties for its divergence on “basic principles”, such as supporting the death penalty.

Interest in climate change has fluctuated in Mexican politics. During a six-year term that ended in 2012, the second PAN president Felipe Calderón significantly raised its status and introduced the nation’s first comprehensive climate legislation.

He also oversaw the COP16 UN climate summit, which took place in 2010 in the coastal city of Cancún.

Calderón’s successor, the PRI president Enrique Peña Nieto, came to power at a time of slow economic growth with a promise to boost the nation’s oil and gas production.

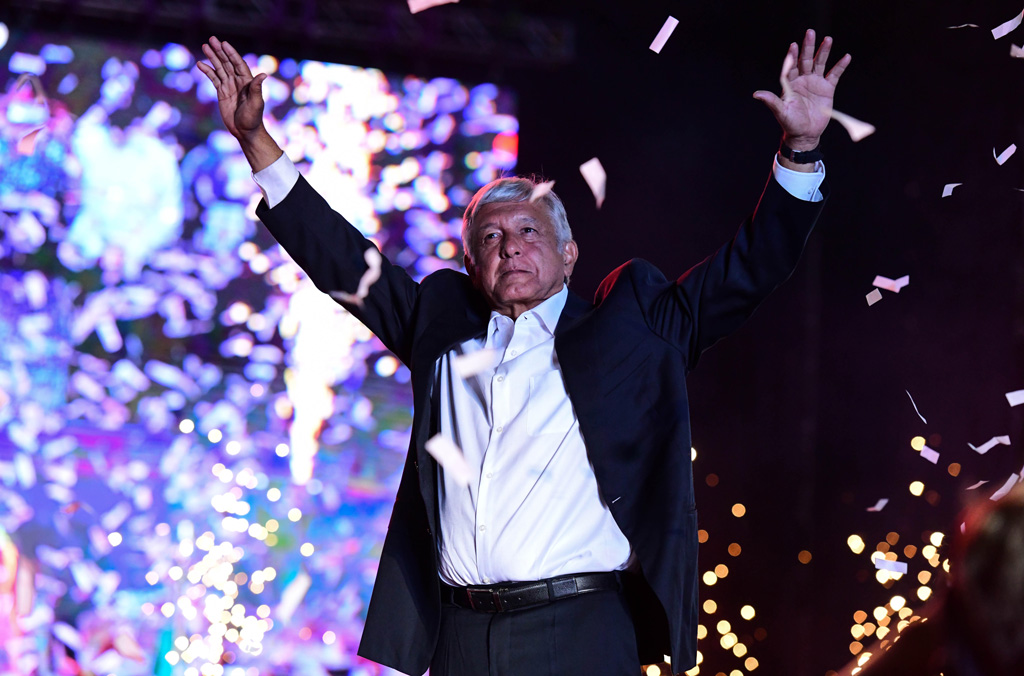

While climate was not always a high priority for Peña Nieto, observers note that it has sunk further under López Obrador, who swept to power on a populist platform promising an array of social programmes in 2018.

While running for president, López Obrador’s environmental manifesto, NaturAMLO – an allusion to his initials, AMLO – discussed climate change, albeit with a focus on adaptation. He pledged to address Mexico’s emissions by planting trees and expanding hydropower dams.

A native of the oil-rich state of Tabasco, López Obrador has poured funding into the state-owned company Mexican Petroleum (Pemex) and curtailed a boom in private renewable projects in favour of energy self-sufficiency based on fossil fuels.

He has cut the budget of the Mexican environment ministry as part of a government austerity programme and criticised environmental NGOs in Mexico for their supposed links with foreign governments.

As a result of all this, Bloomberg has stated that the Mexican president has the “rare distinction of being a leader with leftist roots whose environmental policy is closer to right-leaning climate deniers”.

López Obrador was among the world leaders invited to speak at Joe Biden’s leader’s summit in April, at which the US president urged other nations to “step up” their climate ambitions.

Instead, the Mexican president used his pre-recorded address to justify his nation’s continued exploitation of oil deposits and push a programme in which tree-planters in Central America could access American work visas.

More broadly, the Mexican government has at least paid lip service to tackling climate change on the international stage. However, the framing has been more around adaptation and the nation’s vulnerability to climate change than mitigation.

Despite the current administration’s apparent ambivalence, a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2018 found that 80% of Mexicans saw climate change as a “major threat” to the country, up 28 points from 2013.

As in the US during Donald Trump’s climate-sceptic administration, some cities and states in Mexico have emerged as climate leaders without support from the federal government.

Yet with a midterm election set to take place in June to decide all 500 members of the lower house of Mexican congress and governors in 15 of 32 states, López Obrador’s MORENA party is expected to increase its hold on Mexican politics.

Paris pledge

Mexico’s emissions in 2018 were 695m tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e), according to the CAIT database maintained by the World Resources Institute (WRI), which includes emissions from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF).

Its per-capita emissions are 5.5tCO2e, slightly below the global average.

The nation was one of only a handful to come forward with an updated nationally determined contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement by the end-of-2020 deadline.

However, the new Mexican target remained the same as the previous one, namely to unconditionally reduce emissions by 22% below a business-as-usual (BAU) scenario by 2030 – and up to 36% below BAU, if it receives financial, technical and capacity-building support from other countries.

Crucially, the new NDC also revised the BAU projections upwards, meaning achieving the same target would actually result in higher emissions by 2030. The new document also omitted a reference to Mexico’s emissions peaking in 2026.

According to Climate Action Tracker (CAT) – an independent analysis of climate pledges produced by three research organisations – the unconditional target would previously have led to 763MtCO2e in 2030, excluding LULUCF.

Now, it estimates that the same target would result in 774MtCO2e. This is 76% higher than Mexico’s emissions in 1990.

CAT concluded that the change in baseline for the NDC moved the rating of Mexico’s climate pledge from “insufficient” to “highly insufficient” for achieving international goals.

It noted that the pledge lowers both “climate ambition and transparency, contrary to Paris Agreement rules”.

While the wording of the agreement around submitting new NDCs is somewhat loose, it is generally taken to mean that nations’ should submit more ambitious pledges over time.

This backsliding on pledges reflects a wider trend in current Mexican politics. However, under previous administrations, Mexico has been recognised for its leadership in international climate negotiations.

As a non-Annex I country to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) it did not have to adopt a legally binding mitigation target under the Kyoto Protocol. Annex I status was based on membership of the OECD at the time, which Mexico only joined shortly after the UNFCCC was ratified in 1994.

Nevertheless, Mexico was one of the first countries to adopt a voluntary mitigation target in 2008 and the first “developing country” to submit its NDC in the lead-up to the Paris Agreement in 2015.

It was also one of the first nations to submit a long-term climate strategy after the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2016.

The leaders of Mexico, Canada and the US also agreed at their annual “three amigos” summit in 2016 to a North America-wide target of 50% clean power generation by 2025.

According to WRI, the nation’s position within the OECD has allowed it to play a “a bridging role” in climate negotiations between richer and poorer nations.

Mexico hosted COP16 in Cancún a year after the UN climate talks had largely collapsed in Copenhagen. Despite modest outcomes, the summit was widely viewed as a success and the Mexican leadership was praised.

COP president and Mexican foreign minister Patricia Espinosa was later selected for the role of UNFCCC executive secretary.

Part of the “Cancún agreements” was the launch of the Green Climate Fund, which was, in part, intended to help raise $100bn a year by 2020 to help poorer nations with climate adaptation and mitigation. (This target has not been met, with efforts partly hampered by the US withdrawal from the fund during the Trump administration.)

Mexico was a contributor to the fund in its “initial resource mobilisation” in 2014, pledging $10m of the $10.3bn total, but it has not contributed to the fund’s subsequent replenishment. The nation has also benefited from the fund, with four projects receiving $23m in financing.

Climate policies and laws

In 2012, Mexican parliament passed the General Law on Climate Change, a comprehensive piece of legislation that includes emissions reduction targets and provides the institutional framework for their implementation.

Initially, the law included a 30% reduction in emissions by 2020 compared to BAU and a 50% reduction from 2000 levels by 2050. These objectives were conditional on international support.

It also has a target of 35% clean power generation by 2024 and, in 2015, the Energy Transition Law built on this with shorter-term targets of 25% by 2018 and 30% by 2021. In addition, Mexico has a longer-term target of 50% clean power by 2050.

The general climate change law was amended in 2018 to reference the Paris Agreement and incorporate Mexico’s NDC targets, including its unconditional goal.

These laws have been well received, with Mexico hailed as the “first developing country” and “the first large oil-producing emerging economy” to adopt climate legislation.

In formulating its climate law, Mexico took direct inspiration from the UK’s Climate Change Act, as well as advice from UK officials when creating the law. WWF-Mexico stated in 2012 that the legislation put Mexico in “an elite global club, with the UK and its Climate Change Act as the only other members”.

However, despite these laws, Mexico’s climate progress has been slow and its emissions have continued to rise.

Even accounting for a pandemic-related dip, CAT has concluded that Mexico will “most likely not achieve” its 2020 emissions pledge. Analysis by climate thinktank Ember suggests that the nation only achieved its 25% clean power target last year – two years later than its target.

Unlike the UK’s legally binding system, the Mexican targets are not mandatory and analysis by the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics concluded that the law lacks mechanisms for accountability and enforcement.

As analysis by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) stated at the time, the lack of legally binding emissions limits meant that the “absolute strength of the law and whether it accomplishes its mitigation goals will depend on political will and leadership”.

Implementation of policies in line with the new laws has been patchy. A report by the National Climate Policy Evaluation Committee – a body established by the climate change law – found that for the 2014-2018 period just 43% of policy areas were progressing according to schedule.

Nevertheless, across this period there was some progress, including the expansion of clean energy projects and the development of a carbon tax.

Mexico has also piloted an emissions trading scheme (ETS). The formal launch is currently set for 2022, with up to 700 companies expected to participate.

Wind and solar

Mexico has significant potential for renewable power owing to high solar radiation across most of its territory and high wind speeds, particularly in southern states such as Oaxaca and Yucatan.

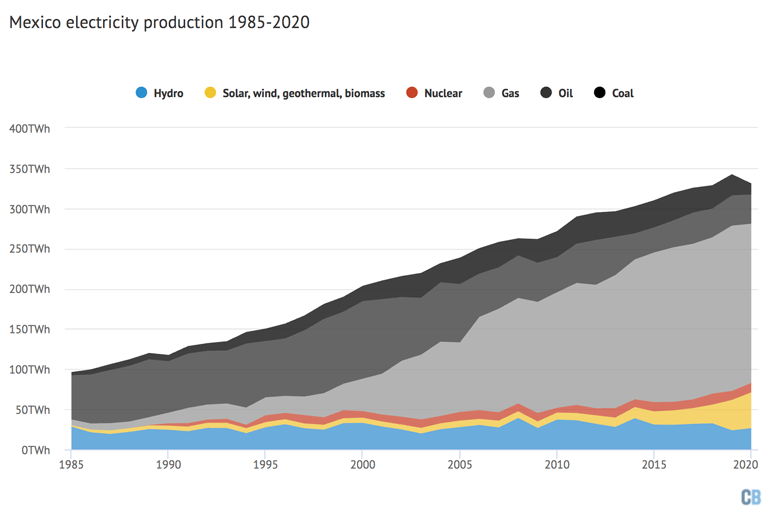

Wind and solar power have grown rapidly in recent years, expanding from 3% of the electricity mix in 2015 to 10% in 2020, according to Ember.

Progress on renewables has largely been tied to government views on the relative roles of the state and the private sector in supplying Mexico’s electricity. Changing political currents in recent years mean the future of Mexican renewables is not guaranteed.

For decades, most of the electricity market was controlled by the state-owned Federal Electricity Commission (CFE), with some private investment allowed in 1993.

The nation’s growing power demand was covered primarily by fossil fuels, as the chart below shows.

In 2013, president Peña Nieto signed into law a comprehensive energy reform which was intended to end CFE’s monopoly and allow greater competition in power generation and supply. It also reopened Mexico’s large oil and gas reserves to external investors.

It brought in two key laws, the Electricity Industry Law and the Energy Transition Law, to encourage private investment in the power sector.

The reform also reiterated a target of generating 35% of Mexico’s electricity from clean sources by 2024, with interim targets along the way.

According to an “energy outlook” published by the International Energy Agency in 2016, the reform was “expected to reverse the country’s declining oil production, increase the share of renewables in the power sector and slow the growth in carbon emissions”.

It included the creation of clean energy certificates (CELs) that set a minimum level of clean electricity consumption for all large consumers, including CFE, and allowed for the purchase and sale of these certificates in a cap-and-trade scheme.

However, the current administration has backtracked on many of the 2013 reforms and tried to limit the privatisation of the energy sector. López Obrador has said he wants CFE’s share of generation to remain at 54%, the level when he took office.

Wind and solar projects tend to be privately owned – often by foreign companies – running counter to the president’s nationalist ideals and desire for energy independence.

He has described wind turbines as “visual pollution” and accused renewables developers of fraudulent activity and corruption.

In 2019, the government cancelled the nation’s fourth long-term clean energy auction, despite previous rounds setting global records for low solar prices. This has created uncertainty for private investment and future energy prices.

Other actions include CFE cancelling the new high-voltage Yautepec-Ixtepec transmission line from the wind power-rich state of Oaxaca and the National Energy Control Center (CENACE) pausing grid connections for new solar and wind power projects.

Finally, during the pandemic the administration has introduced a bill that critics have dubbed the “fuel oil law”, which prioritises power generated by CFE – including that derived from coal and oil – over cheaper, privately owned wind and solar power in the grid.

The government argued that the intermittent nature of renewables would not be able to sufficiently supply the grid during lockdown. [Experience in Europe showed that grids were able to operate reliably despite higher renewable shares during lockdowns.]

The fuel oil law has faced legal challenges in Mexico, with warnings that it could provoke trade disputes with other nations, including the US.

The new bill also modified CELs, allowing older hydropower, nuclear and geothermal plants owned by CFE to obtain them. Prior to the change, only projects built after 2014 qualified for CELs.

Companies responded with legal action when this was initially proposed in 2019, arguing the policy was meant to promote new renewables rather than prop up old infrastructure.

The move to prioritise CFE projects over private investors has since been suspended by a Mexican judge, and a decision from the nation’s Supreme Court on the matter is pending.

If the law does not gain approval from the court, López Obrador has suggested he would change the constitution to allow it, just as his predecessor changed the constitution with his energy reform. A two-thirds majority for MORENA and its allies in the upcoming midterm elections could make this a possibility.

With renewable investments under threat, local governments in states including Nuevo León, Puebla and Querétar have been challenging the federal government’s actions and searching for ways to ensure continued deployment.

When the energy reform legislation of 2013 was brought in, it reiterated Mexico’s goal to generate 35% of its electricity from clean sources by 2024 and imposed interim targets including 30% by 2021. Last year, just 25% of electricity came from clean sources.

López Obrador has said he is still committed to these clean power targets, but analysis by Wood Mackenzie suggests his government is on course to miss them as the current pipeline of wind and solar projects comes to a close.

Missing these national targets could have significant economic consequences. A Mexican government study found that achieving a goal of 43% clean electricity by 2030 could increase employment in the electricity sector by 38% and make “considerable contributions to energy security”.

Hydropower and nuclear

Unlike with wind and solar, López Obrador’s administration has been supportive of hydropower and nuclear plants, which are largely owned and operated by the CFE.

Hydropower supplies 8% of Mexico’s electricity generation, more than any other single renewable source.

However, Mexico only generates around 27 terawatt hours (TWh) of hydroelectric power each year, less than a tenth of US generation and half of Colombia or Venezuela’s.

Expanding the nation’s hydropower capacity has been central to the current administration’s energy goals, with a hydroelectric policy that focuses on modernising existing plants.

CFE owns 59 of Mexico’s 86 hydropower plants, but according to Argus Media, as of 2019, only 14 of these plants were active. The president has said that improving existing dams will be enough to supply the nation’s power needs without the need for new dams.

However, there are concerns that market challenges and pushback from local communities could hamper the development of the nation’s hydropower and leave the power sector reliant on fossil fuels.

According to the Mexican Association of Wind Power, each megawatt-hour (MWh) generated by CFE hydropower plants costs more than double the price of a MWh from the long-term renewable supply auctions cancelled by the government.

Prior to López Obrador taking power, hydropower growth had stagnated amid public opposition to large-scale projects, such as Chicoasen 2 in Chiapas, which has now been given the green light.

Mexico also has two nuclear reactors at Laguna Verde generating around 4% of its electricity. Its first commercial nuclear power reactor began operating in 1989.

The government has renewed the operating licence for unit one of the Laguna Verde plant for an additional 30 years to 2050, by which time it will have been in operation for 60 years.

According to reports, CFE has also been considering the development of new nuclear reactors both at the Laguna Verde site and along the Pacific coast.

Oil and gas

Mexico was, as of 2019, the 13th biggest producer and 13th largest consumer of oil in the world, according to BP data.

Oil production has fallen from its peak in the early 2000s, but it still has a significant place in Mexican culture. Fuel prices and subsidies have been highly political issues in the nation.

In 1938, the state seized nearly all of the assets of foreign-owned oil companies, effectively nationalising the industry. Oil Expropriation Day is a national holiday and many view the state-run Mexican Petroleum (Pemex) as a source of pride.

The Mexican oil boom began in the late 1970s, with Pemex discovering the Cantarell Field – the nation’s largest reserve – in the Gulf of Mexico in 1976. At its peak in 2004, Cantarell was the world’s second largest oil field, producing 2.1m barrels per day.

With oil production in sharp decline and Pemex lacking the resources to tap into its remaining reserves, Peña Nieto’s energy reforms in 2013 were meant to attract private investment and reinvigorate the sector.

However, falling oil prices also hampered hopes of private investment and opponents on the left, including López Obrador himself, saw the move as “theft” of Mexican resources.

When he took over from Peña Nieto in 2018, López Obrador set about modernising fossil fuel plants and building new oil infrastructure. At the heart of his administration’s agenda is the revitalisation of Pemex, which once powered the Mexican economy, but is now the world’s most indebted oil company.

The centre point of this effort is the Dos Bocas refinery in the president’s home state of Tabasco, the construction of which has involved cutting down protected mangrove trees.

The president has vowed to end reliance on fuel imports, but as it stands the nation largely relies on the US to refine its low-quality oil and supply it with petroleum products.

Mexican oil is generally low quality and contaminated with sulphur. As the nation has ramped up its gasoline production it has been left with large volumes of high-sulphur fuel oil owing to its inefficient refineries. This has coincided with a global ban on this dirty fuel in shipping.

As a result, the nation has turned to burning this “combustóleo” in power plants, replacing natural gas which is often imported from the US and further discouraging the development of renewables. Last year, 10% of Mexico’s electricity was produced by burning oil.

The president has also postponed a rule requiring low-sulphur diesel for vehicles until after he leaves office in late 2024.

Switching a power plant from natural gas – which currently provides 60% of Mexico’s electricity – to fuel oil increases its CO2 emissions by 16%, according to BloombergNEF.

Natural gas production in Mexico has been declining for around a decade, with Pemex only managing to slow the decline under the current administration.

Despite this, from the outset the president has said he would ban fracking and has blocked efforts to launch operations in Mexico’s northern border states.

Meanwhile, progress on decarbonising the Mexican transport sector has been slow. Mexico made up more than half of the Latin American electric vehicles market – which is just 1% of the global market – in 2019, but the current administration does not provide any incentives to promote the industry.

Cars are the nation’s biggest export, but there are concerns that the global shift to electric vehicles may leave Mexican factories behind.

Coal

As of January 2021, Mexico had 5,378MW of operating coal plants, according to the Global Coal Plant Tracker. This accounts for 4% of the nation’s total power generation.

Mexico’s electricity production from coal halved compared to the previous year in 2020, the largest percentage reduction of any G20 country.

While this dramatic dip was largely due to Covid-19, over the past five years Mexican coal generation has fallen 60%, according to the climate thinktank Ember.

This decline in coal generation was made up by new wind and solar generation rather than natural gas, Ember says.

However, this trend could be reversed under López Obrador, who has advocated for the reactivation of old coal plants while undermining new renewables development.

The government has allocated a budget for upgrading coal and other fossil-fuelled power plants, some of which had already been set for retirement under the previous administration.

Mexico also operates coal mines, although it is only home to around 0.1% of the world’s reserves.

The president visited the coal mining regions of Coahuila at the end of 2020 to announce the reactivation of the CFE’s coal-fired plants, supplied with Mexican coal. Nevertheless, the CFE has insisted that it will continue to prioritise natural gas generation over coal.

Forestry and agriculture

Tree-planting has been a key part of Mexican environmental policy for years, although it has faced its share of controversy.

In 2007, during his first year as president, Calderón oversaw an initiative that planted 250m trees across the nation, joining in by planting a pine tree in the grounds of his Mexico City residence.

While the scheme was praised by the UN, a Greenpeace Mexico study found that 74% of the trees that had been planted that year died and another 17% were sick. It also drew criticism for failing to offset the extensive deforestation taking place across the country.

According to the Economist, the programme was “widely considered a failure”, with officials admitting at the time that at least 40% of the trees had died.

López Obrador has launched his own tree-planting programme – “Sowing Life” – which has been pitched primarily as a way to create jobs and stem migration by encouraging farmers to stay on their land.

In remarks made during US president Biden’s virtual climate summit in April, López Obrador said that Mexico aimed to expand the programme to Central America.

Calling it “possibly the largest reforestation effort in the world,” the president said the programme would create 1.2m jobs and plant 3bn additional trees. As a slightly incongruous afterthought, he suggested the US should offer work visas to those who had participated.

There is evidence that the programme may actually be having the opposite intended effect.

A study by the World Resources Institute and investigation by Bloomberg suggested the initiative may have caused 73,000 hectares of forest loss in 2019.

Farmers told Bloomberg they had cut down trees in order to access government grants to plant saplings on the land. López Obrador has said he will investigate these claims.

Deforestation continues to be an issue across the nation. According to the FAO, between 2010-2020 Mexico experienced a net loss of 125,100 hectares of forest each year.

Nevertheless, according to a national inventory submitted to the UNFCCC in 2018 by the Mexican government, the nation’s agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) sector has remained a fairly consistent net carbon sink from 1990-2015, absorbing 50-60MtCO2e each year.

(This is different from the LULUCF values in the infographic above, which are based on CAIT data and suggest Mexican land is predominantly a source of emissions. The datasets are not directly comparable as unlike AFOLU, LULUCF does not include agricultural land.)

According to the inventory, livestock is a sizable source of emissions, responsible for around a tenth of the total in 2015.

While there is little political discussion around cutting emissions from the nation’s agriculture, there is recognition that global warming is already having an impact on Mexican farmers.

Impacts and adaptation

According to Mexico’s sixth national communication to the UNFCCC from 2019:

“Mexico is a particularly vulnerable country to impacts of climate change due to its geographical location, its topography and its socioeconomic characteristics.”

As many of these changes are “mostly unavoidable” the document notes that adaptation is “necessary and urgent”.

Located between the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico, and spanning regions of desert, rainforest and mountains, the nation is vulnerable to tropical cyclones and flooding, as well as droughts and heatwaves, all of which can be exacerbated by climate change.

The annual mean temperature of the nation has already risen by around 1.5C since the 1850-1900 period.

In 2021, Mexico experienced one of its most intense droughts in decades, which affected nearly 85% of the country in April and saw more than 60 large reservoirs go below 25% capacity.

Research has also linked climate change to a wider “mega drought” that has been impacting northern parts of the country for almost two decades.

These extreme dry conditions will likely have significant knock-on effects, with one study suggesting that drought-induced crop failures could drive millions of Mexicans to migrate.

A government adaptation document for the coming decade notes that between 1970 and 2013, of the 22 category 3 cyclones that struck the coasts of the Mexican Pacific and Atlantic oceans, 10 had occurred in the previous 12 years.

Climate change has also been linked to the strength of hurricanes that affect Mexico. In coastal regions, sea level rise and storm surges also threaten low-lying infrastructure and the tourism industry.

Mexico has assembled various plans to adapt to the impacts of climate change and adaptation features in the General Climate Change Law itself.

The country’s National Strategy on Climate Change (ENCC) is a planning mechanism for medium- and long-term climate action, which includes adaptation as one of its priorities. It identifies 1,385 municipalities, home to 27 million people, which have high climate-related disaster risk.

The current administration has identified adaptation and nature-based solutions as important areas of focus.

Graphic by Joe Goodman for Carbon Brief.

Data for energy consumption comes from BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2020. Unlike previous country profile infographics, exajoules (EJ) have been used instead of millions of tonnes of oil equivalent (mtoe) as the unit of energy consumption, in line with BP updating its energy outlook units.

Data for greenhouse gas emissions by sector is a combination of three datasets compiled by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), the Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) and CAIT.

Values for methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O) and fluorinated gases cover all sectors and come from the PIK PRIMAP database v2.2. Values for greenhouse gas emissions from LULUCF come from CAIT, although these only go as far back as 1990. This dataset has been used because PIK no longer provides LULUCF emissions data.

The remaining values come from the EDGAR CO2 emissions database. The EDGAR categories described in full are as follows: Buildings (non-industrial stationary combustion: includes residential and commercial combustion activities); Transport (mobile combustion: road and rail and ship and aviation); Non-combustion (industrial process emissions and agriculture and waste); Industry (industrial combustion outside power and heat generation, including combustion for industrial manufacturing and fuel production); Power & heat (power and heat generation plants).

The CAIT database says that Mexico had the world’s 11th largest greenhouse gas emissions (695MtCO2e), including LULUCF, in 2018. Previous country profiles in this series have been based on PIK data, meaning the ranking is different. They will be updated shortly.

Per capita emissions in 2018 come from combining the above 2018 figure for greenhouse gas emissions and the Mexican population in 2018 from the World Bank.

The Mexican pledge to reduce its emissions comes from its official NDC, submitted to the UNFCCC.

-

The Carbon Brief profile: Mexico

-

Everything you need to know about the Mexico's climate and energy policy