In the sixth article of a series on how key emitters are responding to climate change, Carbon Brief looks at Indonesia’s efforts to curb deforestation and tame polluting peatland fires.

Indonesia was the world’s fourth largest emitter of greenhouse gases in 2015. It is the 16th biggest economy and the largest in southeast Asia. Its emissions stem from deforestation and peatland megafires and, to a lesser extent, the burning of fossil fuels for energy.

The country recently overtook Australia again to become the world’s largest exporter of thermal coal. It plans to substantially increase its domestic coal-powered generation – partially in a bid to help close the “electricity gap” between its wealthy and less-connected islands.

The current government has pledged to cut emissions by 29-41% by 2030, compared to a “business as usual” scenario.

The country is holding a general election this April and polls suggest a win for current president Joko Widodo.

(Update 23/04/2019: Joko Widodo has declared victory in the presidential election after unofficial results from private pollsters suggested he had won around 55% of the popular vote. The official results will not be announced until 22 May.)

Politics

Indonesia is the world’s third largest democracy and almost 260 million people live across its chain of islands, of which there are an estimated 17,508. It also has the world’s largest Muslim population and is highly ethnically diverse, supporting more than 300 local languages.

The country has held general elections since 1955, but only began holding presidential elections in 2004. Its current leader, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, was elected in 2014 and will face another election this April. Widodo is a member of the “left-of-centre” Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) and leads a majority coalition government with the support of nine political parties.

Widodo is the first president in Indonesia to not come from an elite military or political background and remains untainted by the corruption allegations that dog other government officials. A year before he was elected, the Economist described him as “an honest man”. However, he faces criticism for doing little to advance human rights during his presidency.

His campaign for reelection is centred around promises to boost economic growth, largely through more infrastructure development, and to increase measures to tackle terrorism and corruption – with any mention of climate change so far “tragically absent”, according to the Jakarta Post, an English-language Indonesian newspaper.

Last year, Widodo boosted subsidies for diesel “amid worries that higher fuel costs [could] threaten his bid for re-election”, according to the Nikkei Asian Review, an Asia-focused financial publication. (He had previously overseen a “big-bang” removal of subsidies in 2015, according to the IEA, in a bid to reform Indonesia’s “decades-old” fuel support system.)

A poll in January by Charta Politika, an Indonesian political consultancy firm, found Widodo had an approval rating of 53.2%. His biggest rival, Prabowo Subianto – a former army general who lost to Widodo in 2014 – had an approval rating of 34.1%.

Indonesia’s president Joko Widodo (2nd R) and his rival ex-general Prabowo Subianto (L Front) talk to the media after a meeting in Jakarta, 17 October 2014. Credit: Xinhua / Alamy Stock Photo.

Research released in February by Jatam, an Indonesian NGO that monitors the mining industry, found that 86% of the $4m in donations reported by the Widodo campaign is linked to big mining and fossil-fuel companies. It also found that 70% of the $3.4m declared by the Prabowo campaign is linked to mining and fossil-fuel firms.

On 17 February 2019, both candidates took part in a televised debate on the theme of “environment, energy and infrastructure”. According to the environmental website Mongabay, both pledged to increase the cultivation of palm oil – the major driver of deforestation in the country. Neither candidate mentioned how they planned to tackle climate change.

Across the country, 41% of people describe themselves as “very concerned” about climate change, according to a poll taken in 2015. This is lower than the proportion of people concerned in neighbouring Vietnam (69%), Malaysia (44%) and the Philippines (72%), but equal to the proportion in the UK.

Paris pledge

Indonesia is part of five negotiating blocs at international climate negotiations. These include the Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDCs); the G77 and China; the Coalition for Rainforest Nations; the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the Cartagena Dialogue. (More information on each group is available in an in-depth explainer of negotiating blocs by Carbon Brief.)

The country’s annual greenhouse gas emissions were 2.4bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e) in 2015, according to data compiled by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK). The figure includes emissions from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF). Indonesia’s emissions represented 4.8% of the world’s total global emissions for that year.

Its per-capita emissions were 9.2 tonnes of CO2e that year – larger than the global average (7.0 tonnes of CO2e) and the average in China (9.0 tonnes of CO2e), the UK (7.7 tonnes of CO2e) and the EU (8.1 tonnes of CO2e).

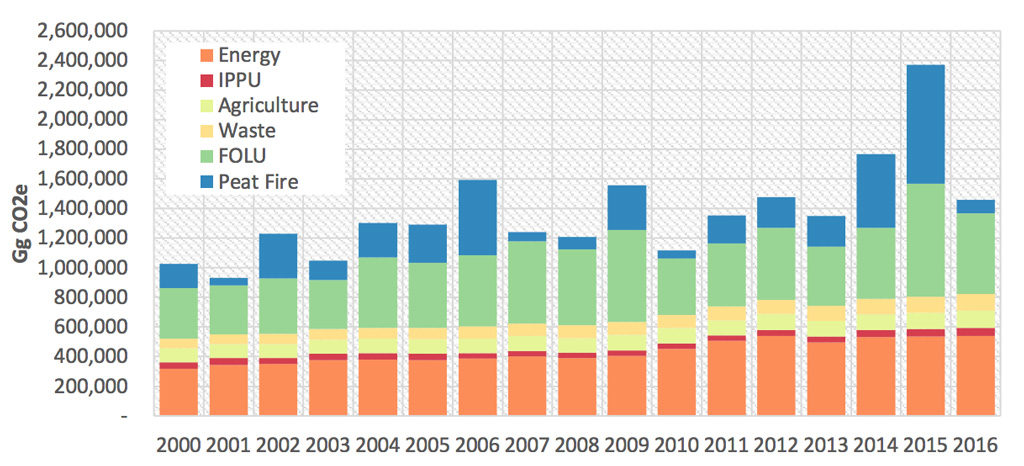

However, it is worth noting that Indonesia’s total emissions vary widely from year to year, largely as a result of variable peatland “megafires”.

The chart below, which is taken from Indonesia’s latest biennial report to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), gives an idea of how the country’s peatland fires can shift overall emissions.

The chart shows emissions from peatland fires (blue), forestry and other land use (“FOLU”; green), waste (yellow), agriculture (pale green), industry (“IPPU”; red) and energy (orange). (It is worth noting that the figures shown are self-reported.)

Indonesia’s total emissions from 2000-16. Emissions from peatland fires (blue), forestry and other land use (“FOLU”; green), waste (yellow), agriculture (pale green), industry (“IPPU”; red) and energy (orange) are shown. Emissions are shown in gigagrams of CO2 equivalent (GgCO2e, millions of tonnes). It is worth noting that the figures are self-reported. Source: Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Indonesia.

Indonesia’s climate pledge (“nationally determined contribution”, or NDC) targets a 29-41% reduction in emissions by 2030, compared to “business as usual”. The upper end of this range, conditional on “support from international cooperation”, would see emissions in 2030 remain at or below recent levels.

This pledge was submitted to the UNFCCC in the lead up to the Paris climate conference. Indonesia ratified the Paris Agreement in 2016.

The country aims to decarbonise its economy “in a phased approach” – namely, through policies for “improved land use and spatial planning, energy conservation and the promotion of clean and renewable energy sources, and improved waste management”.

This pledge has been rated “highly insufficient” by Climate Action Tracker (CAT), an independent research project tracking climate policies. The rating suggests that Indonesia is not committing its “fair share” to the emissions cuts needed to limit global warming to less than 2C. If all countries had similar targets, temperatures would reach 3-4C by 2100, the analysis finds.

Indonesia’s emissions have increased at a faster rate than expected in recent years, CAT says, and, under current policies, “might even double by 2030”, when compared to 2014 levels.

Deforestation, palm oil and fire

Indonesia contains 10% of the world’s tropical rainforests and 36% of its tropical peatlands.

Tropical peatlands are wet and swampy forested environments with soil that can hold up to 20 times more carbon than other types of mineral soil. It is estimated that Indonesia’s peatlands hold around 28bn tonnes of carbon – the equivalent of nearly three years of global fossil fuel emissions.

A Bornean Orangutan feeds on aquatic plants in Tanjung Puting National Park, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Credit: Rosanne Tackaberry / Alamy Stock Photo.

Indonesia also accounts for 53% of the world’s palm-oil cultivation, a product ubiquitous in packaged food, fuels and cosmetics. It is the country’s third most profitable export after coal and petroleum, and the industry employs an estimated 3.7 million people.

The thirst for palm oil has transformed the country’s landscape. From 2000 to 2015, Indonesia lost an average of 498,000 hectares of forest each year – making it the world’s second biggest deforester after Brazil.

Much of this past deforestation involved “slash and burn” clearing, which has played a large role in driving polluting megafires across the country’s peatlands. When fires rip across peatlands, much of their vast stores of carbon are released into the atmosphere.

![]()

The practice of draining peatlands has also heightened the risk of megafires. In order to grow palm oil and other crops, such as timber, peatlands are often drained of their natural moisture – leaving them dry and more likely to catch alight.

In 2015, the number of peatland fires spiked – causing greenhouse gas release on the same scale as Brazil’s total annual emissions. On some days, Indonesia’s fire emissions alone were higher than those from the entire US economy. (The fires in 2015 were fanned further by hot dry conditions as a result of the natural climate phenomenon El Niño.)

The smoke from the fires led to 19 deaths and caused up to half a million people to suffer from respiratory illness, the Guardian reported at the time.

A soldier tries to extinguish a peatland fire in South Sumatra, Indonesia, 12 September 2015. Credit: Xinhua / Alamy Stock Photo.

That year, changes to land-use, peatlands and forests accounted for 79% of Indonesia’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

In the wake of the deadly haze, Widodo announced a nationwide moratorium on the draining of Indonesia’s peatlands. He later set up the Peatlands Restoration Agency and tasked it with restoring 2m hectares of tropical peatlands by 2020.

From 2016 to 2017, forest loss in Indonesia fell by 60% – in part due to the moratorium, analysts say.

In September 2018, Widodo issued a presidential instruction to place a moratorium on new permits for palm plantations for three years.

However, “threats remain”, analysts say. More than a quarter of the peatlands put under protection in 2015 had already been auctioned off to palm oil and timber firms. To compensate these companies, the government is operating a “land swap” scheme, offering firms access to unprotected land. Some groups warn this could clear the way for more deforestation.

This year, the European Union tightened its rules on biofuels in an attempt to limit the use of palm oil linked to deforestation – a move that was bitterly opposed by Indonesian ministers.

A recent investigation by Unearthed uncovered evidence suggesting that Indonesian ministers had tried to pressurise European countries, including the UK, into opposing the rule change. The investigation also found that, in 2016, France scrapped a proposed tax on unsustainable supplies of palm oil after being warned it could lead to the execution of a French citizen in Indonesia.

Coal

Indonesia is the world’s fifth largest producer of coal and is home to the world’s 10th largest coal reserves, according to the latest BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

Around 80% of Indonesia’s coal is exported, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). From 2000 to 2014, Indonesia’s coal exports quadrupled, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

In 2017, Indonesia overtook Australia to become the world’s largest exporter of thermal coal, which is used for power generation, according to the IEA.

China is the primary buyer of Indonesian coal and received 31% of its exports in 2017, says the IEA. Other key customers include India, Japan and South Korea.

Coal mining has many environmental impacts in Indonesia. For example, the shipping of mined coal from Kalimantan has destroyed “hundreds of square metres” of tropical coral reefs, according to Greenpeace.

Around 58% of Indonesia’s electricity was generated by coal in 2017. This is shown on the chart below (black area).

Chart by Carbon Brief using HighchartsThe country ranks 10th in the world for total coal capacity (29,307 megawatts), but fifth for planned capacity (24,691MW).

However, it is worth noting that Indonesia has repeatedly scaled back its planned coal capacity. In 2015, Indonesia had plans for 45,000MW of new coal. This figure later fell to 34,000MW in 2018 and again to around 25,000MW this year, according to data from Global Energy Monitor.

In its latest report on the global coal market, the IEA identifies Indonesia as a major driver of rising demand over the next five years. It says demand for coal-fired power in the country is likely to increase as a result of “robust economic growth, a rising population and an expanding middle class”.

In 2015, Widodo unveiled an ambitious plan to develop 35,000MW of new power by 2019 – in part to address the “electrification gap” between the country’s wealthy islands, such as Bali, Java and Sumatra, and its smaller, more isolated islands. (The target was later pushed back to 2024.)

Interactive map of historical and planned coal power plants in Indonesia and South East AsiaThe government sees coal-fired power as a “cheap and easy” way to help meet its target, according to the Financial Times.

(However, analysis by Carbon Tracker found it could become cheaper to build new renewables than new coal between 2020 and 2022, with new renewables becoming cheaper than existing coal by 2028.)

In March 2018, officials capped the price of domestic coal for power stations for two years – a move intended to help keep electricity prices low around the time of this year’s election, analysts say.

Coal has not been a major talking point in Widodo’s campaign for reelection, according to Mongabay. However, his rival Prabowo has called for coal use to be slashed and replaced with renewables, according to the Jakarta Post.

Renewables

Just 5% of Indonesia’s electricity came from renewables in 2017 – the vast majority of this from geothermal sources. However, the government has pledged to source 23% of its energy from renewables by 2025 and 31% by 2050.

Indonesia is the world’s second largest producer of geothermal power after the US.

The country has installed 1,925MW of geothermal power. However, its untapped geothermal resources are estimated to total 29,000MW – 40% of the world’s total geothermal reserves.

A Buddhist monk sits in front of the Kawah Ijen volcanic crater as sulphur gases are released, east Java, Indonesia. Credit: Malgorzata Drewniak / Alamy Stock Photo.

Indonesia is a hotspot for geothermal resources because of its volcanic activity. It sits on the Pacific Ring of Fire and is home to 139 volcanoes, according to the Global Volcanism Program.

The country aims to have 7,200MW of geothermal energy by 2025, which would make it the biggest geothermal producer in the world.

Widodo opened the country’s first wind power farm in July 2018. The Sidrap Wind Farm, the largest of its kind in southeast Asia, produces 75MW of electricity and supplies power to Sulawesi, an island east of Borneo. A second 72MW wind farm is currently under construction on the island.

Indonesia’s president, Joko Widodo, inaugurates Sidrap Wind Farm in South Sulawesi, 2 July 2018. Credit: Yermia Riezky Santiago / Alamy Stock Photo.

The country currently has just 16MW of solar power, according to statistics from the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).

However, the government aims to have 6,400MW of solar and 1,800MW of wind by 2025, according to a report from IRENA.

Yet Indonesia “could feasibly exceed its current goals and deploy even more renewables”, the report says. If policies were adjusted, Indonesia could achieve its 2050 renewables target by 2030, it concludes.

The analysis notes that the potential of solar power is particularly underestimated by current government policy. With new policies and investment, solar has the potential to “provide electricity to nearly 1.1m households in remote areas that currently lack adequate access to electricity”, it says.

Climate laws

Indonesia’s legal system is based on Roman-Dutch law, custom and Islamic law. A wide range of legislation is produced and exists in a hierarchy. This hierarchy is as follows (in order of importance): the 1945 constitution; MPR resolution; law; government regulation substituting a law; government regulation; presidential decree; regional regulation.

Much of Indonesia’s climate-related legislation is directed towards tackling emissions from the forest sector. Such laws, discussed in more detail above, include moratoriums on the draining of peatlands and the conversion of primary rainforest.

In September 2018, Widodo issued a presidential decree to place a moratorium on new permits for palm plantations for three years.

The energy sector is also subject to climate-related regulations. The government issued a regulation in 2014 which contained a pledge to source 23% of its power from renewables by 2025 and 31% by 2050 – up from 5% today.

Indonesia has targets to improve energy efficiency. Its National Master Plan for Energy Conservation (RIKEN) sets a goal of decreasing energy intensity by 1% annually until 2025.

In October 2017, the government announced a new initiative aimed at incorporating climate action into the country’s development agenda. (The country has four separate five-year development plans spanning the period 2005-2025).

The country’s National Medium Term Development Plan for 2015-19 says that a “green economy” should be at the foundation of Indonesia’s development.

This plan targets the eradication of illegal logging, fishing and mining and increased participation of local people in forest management. It also sets out aims to increase vulnerable communities’ resilience to climate change impacts.

It specifically targets emissions cuts from five “priority sectors”, including forestry and peatlands, agriculture, energy and transportation, industrial and waste.

On 25 March 2019, the government launched a report looking at how climate action can be incorporated into the country’s development plan for 2020-25.

The report finds that a “low carbon” development pathway could drive a GDP growth rate of 6% a year until 2045, higher than the rate expected under a “business-as-usual” pathway. This path could also cut emissions by 43% by 2030, when compared to “business-as-usual” – exceeding the country’s current national climate targets.

Climate finance

Indonesia has pledged to cut its emissions by 29-41% by 2030, in comparison to “business as usual” – but the top end of this pledge is conditional on “support from international cooperation”.

The pledge did not, however, specify how much aid it would need to reach the upper end of its target. A separate government document published at the time reported that meeting the country’s renewable energy target alone would cost $108bn.

Indonesia is a major emerging market economy, but its population faces steep financial inequality. A report by Oxfam in 2017 found Indonesia’s four richest men now have more wealth than 100 million of the country’s poorest people.

Analysis by Carbon Brief suggests that Indonesia is the world’s sixth largest recipient of climate finance, having received an average of $952m a year from 2015-16.

Further Carbon Brief analysis shows that, by 2016, Indonesia had been awarded $362m in investment from the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and the Climate Investments Fund (CIF).

Notable schemes financed by the multilateral climate funds include a $150m project to develop private sector geothermal energy and $18m for a community-led project to tackle forest degradation.

Impacts and adaptation

As a highly populous nation spread across a chain of tropical islands, Indonesia is considered to be highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

Sea level rise threatens the 42 million people who live less than 10m above sea level in Indonesia. A one-metre rise in sea levels could inundate 405,000 hectares of Indonesia’s coastal land and cause low-lying islands to disappear.

The country’s capital, Jakarta – which is home to 10 million people – is acutely threatened by sea level rise and has been described as the “fastest sinking city” on Earth. The threat of sea level rise has been compounded in the city by illegal well digging, which is causing the ground to plummet.

Increased rainfall is projected for most of Indonesia’s islands, except for its southern islands, including Java, where it is projected to decline by up to 15%.

Rainfall increases and decreases could boost the risk of flash flooding and droughts, respectively. Indonesia’s megacities are particularly vulnerable to flash flooding, which can trigger devastating landslides.

The timing of the country’s annual monsoon could also be impacted by climate change. Research suggests the risk of a 30-day delay to the monsoon could reach 40% by 2050, compared to 18% today. This could have large consequences for agricultural production.

Carbon Brief analysis finds that average temperatures on Indonesia’s islands have already risen by around 1.2-1.5C since the start of the industrial era.

Increased temperatures – in addition to changes in the natural climate phenomenon El Niño – could further raise the risk posed by forest fires. As well as accelerating climate change, fires pose a risk to Indonesia’s biodiversity. Indonesia is home to 12% of the world’s mammal species, 16% of its reptile species and 17% of its bird species.

Male Lesser Bird-of-paradise in courtship display, Papua, Indonesia. Credit: Gabbro / Alamy Stock Photo.

Indonesia launched its National Action Plan on Climate Change Adaptation (RAN-API) in 2012. In the foreword of the report, Endah Murniningtyas, former deputy minister for natural resources and environmental affairs, wrote:

“As the largest archipelago nation in the world, Indonesia is one of the countries that are most vulnerable to climate change.”

The report outlines a plan to improve Indonesia’s resilience to climate change, namely by taking measures to improve energy and food security and to boost the resilience of its forest ecosystems. The report also identifies small islands, coastal regions and cities as “special areas” that most require stronger adaptation measures.

Infographic by Tom Prater

-

The Carbon Brief Profile: Indonesia

-

Everything you need to know about Indonesia's climate and energy policy