Thames Barrier’s extraordinary year prompts government to reconsider long term flood plans

Carbon Brief Staff

03.13.14Carbon Brief Staff

13.03.2014 | 3:00pmAre the Thames’ flood defences still up to the job? That’s the question on London mayor Boris Johnson’s lips.

He’s called for a review of the capitals flood prevention plans after this winter’s extreme wet weather pushed the number of times the Environment Agency needed to use London’s main flood defence, the Thames Barrier, to unprecedented levels.

As the Thames Barrier breaches the Environment Agency’s own 50 closures per year limit for the first time, we look at when it thinks the risk of London flooding might get bad enough for the government to need to take action.

Extreme weather

The Thames Barrier earned its keep this winter, keeping the flood waters at bay more than twice as often as it ever had before.

That’s led some – including London’s mayor Boris Johnson – to wonder whether the current plans to protect London from flood risk are enough.

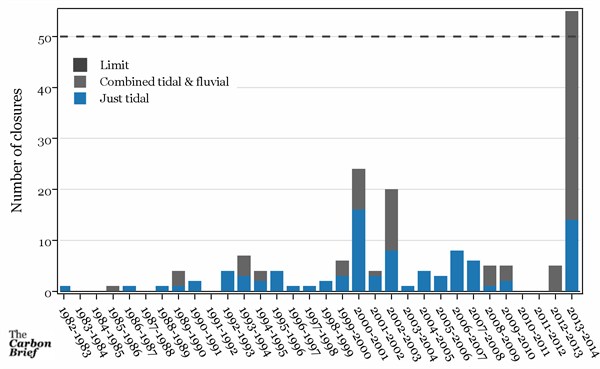

Environment Agency data shows the barrier has been closed 173 times to prevent flooding in its history, with over 50 of the closures in the winter of 2013/14. This graph gives an idea of quite how extraordinary this winter was:

The Environment Agency predicts the flooding risk in this country is likely to increase in the next few decades as a result of climate change. That’s concerning, as the Environment Agency says that if the barrier is closed 50 times a year on average or more, new defences will need to be put in place.

Thresholds

The Thames Estuary 2100 Plan lays out a range of options the government can choose to implement if it is concerned about the increased risk of flooding. The accompanying technical document identifies three thresholds that would trigger a decision on new defences.

Threshold 1 is the level at which the current flood defences can no longer cope. Threshold 2 would be passed if the current Thames Barrier and improved defences upriver of the barrier look like they could get overwhelmed. Threshold 3 is set at a point where an improved Thames Barrier combined with increased flood storage and better defences upriver and downriver are no longer enough to keep the floods at bay.

The point at which the Environment Agency decides each threshold is passed is based on monitoring three things:

Sea level rise: The existing system should be able to withstand around 0.5 metres of sea level rise, according to the Environment Agency’s report. Any rise above that level would make flood defence improvements necessary – with a new set of improvements needed for a rise of around 1 metre (threshold 2) and approximately 1.5 metres (threshold 3).

Tidal surges: The Thames is particularly vulnerable to these surges of water. When they are generated in the Atlantic, they can funnel down the North Sea, into the English Channel, and up the Thames Estuary toward London. When such surges coincide with high tides, they can raise the sea level in eastern England by more than two metres. Sea level rise as a consequence of climate change could contribute to higher storm surges, further increasing the risk of flooding.

Operational capacity: The Environment Agency says the Thames Barrier reaches its limit of effectiveness when it is being used 50 times a year on average (and is part of threshold 1’s criteria). Other barriers have similar restrictions. The more the Thames’ flood defences get used, the more maintanence they need, and the greater the urgency for improving the defences. If the current flood defences get used more often than expected, and degrade more quickly as a consequence, then the thresholds get passed sooner.

But pinning down precisely when the thresholds are likely to be passed is a challenge due to the complexity of the UK’s flood defences.

For instance, improving one part of the UK’s flood defence system may allow another part to operate effectively for longer – delaying when the next threshold will be passed. For example, raising the upriver defences may mean the Thames Barrier can be closed less often, allowing it to be used for longer without technological improvements (increasing the amount of time between threshold 1 being passed, and hitting threshold 2).

Furthermore, while scientists warn that climate change increases the risk of flooding due to sea level rise and more intense rainfall, the rate at which this may occur is uncertain.

So zeroing in on exactly when the government will have to make decisions about the future of the Thames’ flood defences is difficult.

Performing well

The UK has just experienced an exceptionally wet and stormy winter, but this year’s weather may be a one-off. And the Environment Agency is keen to stress that this year, the Thames Barrier has done its job.

It told Carbon Brief the barrier “continues to operate exceptionally well thanks to day to day maintenance, replacing parts and regular inspections”. So there’s no suggestion the barrier is in trouble.

The agency also says the figures in the strategy “should be taken as an average over time”. This means closing the barrier 50 times in any one year does not itself increase the chance of it failing to unacceptable levels.

While its plan suggests a new barrier would be able to withstand even the worst expected impacts of climate change, it would cost billions of pounds and take decades to build.