Survey: ‘Very few’ Africans place responsibility for climate action on ‘rich nations’

Ayesha Tandon

04.10.25Ayesha Tandon

10.04.2025 | 5:14pmA new survey reveals that “very few” Africans place responsibility for climate action on “rich countries” – despite the long history of carbon emissions from the most developed nations.

The study, published in Communications Earth & Environment, presents the results of a survey of more than 50,000 people across 39 African countries conducted over 2021-23.

The authors find that just half of survey respondents have heard of climate change.

Of these, 45% say they believe their own government is primarily responsible for reducing the impacts of climate change and 30% say “everyday Africans” bear the greatest responsibility.

Just 13% of survey respondents put the onus for tackling climate change on “historical emitters”.

African citizens with high levels of education, lower levels of poverty and greater access to the internet and social media are more likely to say that “rich” countries have the primary responsibility for climate action, the study finds.

A scientist who was not involved in the study tells Carbon Brief that the “low attribution of responsibility” to the countries most responsible for historical emissions is “concerning given the disproportionate climate burdens borne by Africa”.

A study author tells Carbon Brief that it is “very interesting to see that at a local level, there is a lot more responsibility that Africans themselves place on their own government for responsiveness”.

He calls the findings “a bit of a wake up call for African governments to be more responsive to their own citizenry in responding to climate change”.

Afrobarometer

Africa is home to some 1.5 billion people, making up around 19% of the world’s population. However, the continent is only responsible for 3% of cumulative global emissions.

At the same time, African people are already facing disproportionate climate impacts. A recent report from the World Meteorological Organization found that African countries are already losing 2-5% of their GDP due to “climate-related hazards” including droughts, floods, cyclones and heatwaves.

At international climate negotiations, developing nations and island states have long argued that wealthy countries, who have produced the majority of global emissions, bear most responsibility for climate action. This includes making rapid cuts to their own emissions and providing billions of dollars in climate finance to help developing nations.

However, the new study finds that “everyday Africans” do not often share these views.

To gauge the opinions of the public in African countries, the authors use survey results collected by Afrobarometer – a not-for-profit group that conducts public attitude surveys on a wide range of topics including democracy, the economy and society.

Study author Dr Nick Simpson – chief research officer at the University of Cape Town‘s African Climate and Development Initiative Climate Risk Lab – tells Carbon Brief that Afrobarometer provides the most comprehensive survey of African countries to date.

African experts have spent decades developing the survey, so the questions “reflect important priorities on the continent” and speak to “lived realities in Africa”, he says.

The study authors use results from Afrobarometer surveys conducted in 39 African countries over 2021-23. A sample of more than 53,400 people were asked: “Have you heard about climate change, or haven’t you had the chance to hear about this yet?”

Around half of the respondents said they had heard of climate change. The study authors found that people with a higher level of education – often men – were more likely to have heard of climate change.

(This is in line with a 2021 paper from the same team, which found that climate change literacy ranges from 23-66% across different African countries. According to the study, climate change literacy rates were 12.8% lower for women than men on average.)

People who said they had heard of climate change were then asked a series of further questions.

Responsibility for climate action

The Afrobarometer survey asked respondents a range of questions about which groups can, and should, take action on climate change. The first question was: “Who do you think should have primary responsibility for trying to limit climate change and reduce its impact?”

Respondents were presented with a range of options including business and industry, their national government, “rich” or developed countries, everyday Africans in their country, traditional leaders, or someone else.

Across the 39 countries surveyed, 45% of the Africans who have heard of climate change say they believe that their own government is primarily responsible. Meanwhile, 30% attribute primary responsibility to “everyday Africans” themselves.

Only a minority of Africans place the burden of responsibility on richer nations. The study finds that 13% say that “rich countries” bear the primary responsibility and 8% put the onus on industry.

Dr Stella Nyambura Mbau is a lecturer at Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology and was not involved in the study. She tells Carbon Brief that “the low attribution of responsibility to historical emitters is concerning given the disproportionate climate burdens borne by Africa”.

However, she says that the “emphasis on government responsibility aligns with my call for policymakers to integrate grassroots knowledge into adaptation efforts”.

Dr Shehnaaz Moosa – the director of not-for-profit SouthSouthNorth – tells Carbon Brief that “it makes sense” that African citizens see their own governments as responsible for climate action, because they “do not understand the systemic complexities” in historical responsibility for global emissions.

Study author Simpson adds:

“I think there was a big assumption out there that, across Africa, there’s a general global-south view that the west is to blame for climate change and the historical emitters are responsible.”

He tells Carbon Brief that although this is the position of African governments and negotiators at UN climate talks, it is “very interesting to see that at a local level, there is a lot more responsibility that Africans themselves place on their own government for responsiveness”.

Simpson tells Carbon Brief that the findings are “a bit of a wake up call for African governments to be more responsive to their own citizenry in responding to climate change”.

Literacy, poverty and corruption

The tens of thousands of Afrobarometer survey respondents come from a range of backgrounds, including different ages, levels of education, access to media and standards of living. Information on all of these variables was collected during the survey.

The authors used a regression analysis – a statistical method to determine the link between two variables – to identify which factors affect an individual’s attribution of responsibility for climate change.

The authors find that Africans with higher levels of education are “significantly more likely” to believe that rich countries have the primary responsibility for climate action. Access to new media sources (such as the internet and social media) is linked to a shift in responsibility away from the government and toward industry, they add.

Meanwhile, people who believe their government is corrupt are less likely to say their government bears the primary responsibility for climate action, according to the study.

To further investigate the link between corruption and perceived responsibility for climate action, the authors assess the “professionalism” of different regions. They define high professionalism as a region with a wide range of services that are easy to use and free from corruption.

In regions with high professionalism, the authors find that people are more willing to address climate change and also more willing to hold the government accountable.

According to the authors, this could lead to a “virtuous cycle” in which improved services allow individuals to take on “climate-related actions”, the paper suggests.

Respondents were also asked questions about which groups have the ability to address climate change. The study says that “lower levels of poverty, higher levels of education and more frequent access to new media” are linked with the belief that everyday Africans can take action to address climate change and that their government should do more.

Meanwhile, factors including gender, community engagement and access to the traditional news sources of radio and newspapers have “little to no relationship with attribution of responsibility for addressing climate change to different actors”, the study finds.

National responses

The authors also break the responses down by country.

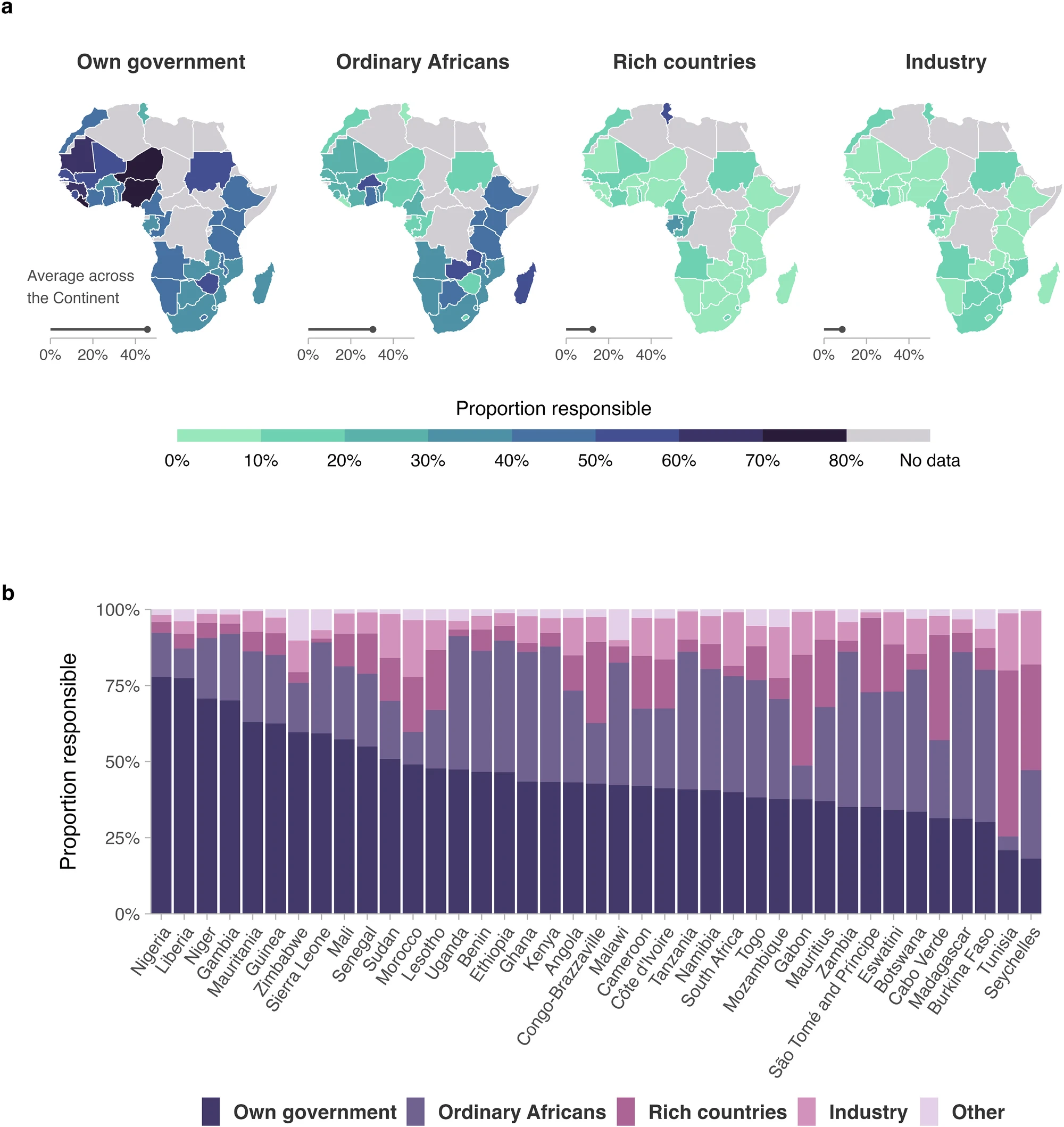

The chart below shows country-level answers to the question: “Who do you think should have primary responsibility for trying to limit climate change and reduce its impact?”

The maps (top) show the proportion of respondents who choose “own government”, “ordinary Africans”, “rich countries” and “industry”, where darker colours indicate a higher proportion of respondents.

The bar chart (bottom) shows the same results. Each vertical column represents a different country and is split into different coloured sections to show the spread of responses.

The paper finds that respondents in countries including Madagascar, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Kenya, Madagascar and Zambia say that “ordinary Africans” bear the main responsibility for climate action. According to the authors, survey participants in these countries span a range of regions and income levels.

The authors find that Nigeria – Africa’s most populous country – has the highest proportion of respondents who place primary responsibility for climate action with their government.

Meanwhile, Tunisia is the only country to attribute most responsibility to rich countries. The study finds that 55% of Tunisians surveyed attributed responsibility to wealthy countries, while only 5% put the onus on ordinary Tunisian citizens.

Simpson tells Carbon Brief that this is probably due to the “high education level” in the country.

The authors highlight four small island states – Cabo Verde, Mauritius, the Seychelles and Sao Tome & Principe – whose respondents were more likely to attribute responsibility to rich countries than the continental average.

“This may reflect an awareness that these populations face growing risk of sea level rise,” the authors say.

Climate literacy

Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology lecturer Mbau praises the scope of the study, noting that “African perspectives are often underrepresented in global climate”.

She tells Carbon Brief that the methodology of the study is largely robust, but adds:

“The exclusion of respondents unfamiliar with climate change risks overlooking their place in this conversation, especially because they represent the majority of the African population.”

She advocates for “qualitative methods” to be used to capture “cultural and contextual nuances, such as how Indigenous knowledge interacts with science”.

Mbau – who has written about the “scarcity of factual understanding” about climate change in rural sub-Saharan Africa – emphasises the need to identify how climate change awareness is “cultivated” and to produce “localised, language-specific climate communication”.

Separately, Moosa tells Carbon Brief that the study is a “great starting point to engage African governments on how they respond to the climate crisis, given that their citizens have this expectation of them”.

Andrews T., et al (2025), Most Africans place primary responsibility for climate action on their own government, Communications earth & environment, doi:10.1038/s43247-025-02244-x

-

Survey: ‘Very few’ Africans place responsibility for climate action on ‘rich nations’