Roz Pidcock

26.02.2014 | 5:45pmA prestigious journal has released a special issue on what’s become something of a preoccupation in the crossover between science and mainstream media recently – an apparent slowdown in surface warming over the last decade or so.

Nature Climate Change dedicates a whole issue to the so called ‘pause’ – looking at how scientists, the public and the media have been talking about it.

The issue talks a lot about lessons for scientists in engaging with the media, but is it worth so much soul-searching when evidence suggests the ‘pause’ has barely made a ripple in the public consciousness?

A lively debate

Since the late 1990s, global average temperature at earth’s surface has risen slower than in the preceding two decades. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s recent report said the rate of warming over the past 15 years has been 0.05 degrees Celsius per decade – quite a bit smaller than the 0.12 degrees per decade calculated since 1951.

The apparent slowdown is a hot topic, and not just in the science world. Evidence of the ‘pause’ in surface warming “has sparked a lively scientific and public debate”, says the Nature Climate Change editorial.

Media pickup

An early outing for the ‘pause’ as a concept was an op-ed in the Telegraph in 2006. The piece claimed global warming had “stopped”, triggering a series of articles in parts of the media since then.

Nature features a commentary by the University of Colorado’s Max Boykoff, which tracks the ‘pause’ story in the media. He says:

“While this meme had been circulating sporadically for a number of years before, media attention to this phenomenon really picked up steam in 2013”

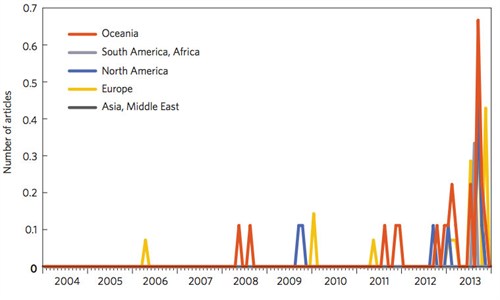

His research tracks media coverage of ‘global warming’ and ‘pause’ or ‘hiatus’ in headlines and lead paragraphs in 50 media sources across 20 countries and six continents between January 2004 and December 2013. The 2013 peak is evident.

Trend in media discourse on the climate slowdown 2004 to 2013. Source: Max Boykoff ( 2014)

Pacific holds the key

Scientists have long known that natural cycles that can temporarily amplify or dampen the warming we see at the surface. But possible explanations for where the extra heat is going have only started to come through in the literature very recently.

An article in the special issue by Yu Kosaka from the University of Hawaii reviews recent studies pointing to natural cycles in the Pacific Ocean. Earlier this month, scientists proposed a strengthening of trade winds is drawing heat into the deep ocean.

While global average surface temperature rise may have been unremarkable in the last 15 years, another paper in the special issue finds there has been “no pause in the evolution of hot extremes over land since 1997”. In fact, such events have increased in the recent decade. This raises an important point about language, the authors say:

“[I]t would be erroneous to interpret the recent slowdown of the global annual mean temperature increase as a general slowdown of climate change.”

And while surface temperature is just the measure we’re most familiar with, there are other indicators of a warming climate. In the past 15 years, the oceans have warmed, the amount of snow and ice has diminished and sea levels have risen, explains Lisa Goddard, an expert in climate variability at Columbia University.

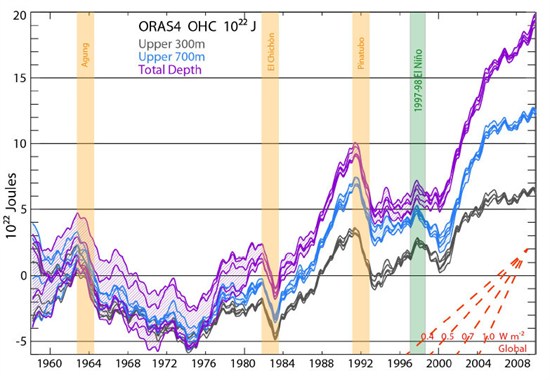

The purple lines in the graph below show how the heat content of the whole ocean has changed over the past five decades.

Source: Balmaseda et al., (2013)

Such distinctions haven’t made it into the media so successfully, however. Boykoff’s analysis indicates this kind of scientific detail often gets lost against the “lure of a captivating headline”.

Element of surprise

When the ‘pause’ hit the headlines, the idea that warming could slow down and speed up rather than climbing smoothly came as a surprise to the public, says the editorial. And a commentary by climate scientists Ed Hawkins, Tamsin Edwards and Doug McNeall argues:

“[T]o our knowledge, the possibility that warming might slow due to internal variability was not highlighted by the mainstream media prior to 2006, raising the possibility that climate scientists did not stress the importance of such variability enough.”

For example, they say BBC science editor David Shukman remarked at a 2013 press conference that he had “never heard leading researchers mention the possibility [of a slowdown] before”.

The scientists say it’s possible the slowdown was communicated to the media but “subsequently ignored as not newsworthy”.

But they suggest scientists should shoulder some of the blame for emphasising the combined ‘most likely’ outcome from lots of models, which smooths out the temporary ups and downs. The real world will behave more like an individual model run – which does show variations – than the average from all the models together, the scientists explain.

Time to mobilise

The issue also explores climate change skeptics’ role in the story of the ‘pause’. Bob Ward, policy and communications director at the London school of Economics, says in an interview that skeptics quickly mobilised a campaign to weaken the case for government action on climate change.

But Ward suggests that while skeptics have muddied the waters, scientists should have been quicker to respond. He adds that scientists have exacerbated the problem because they are too keen to talk about uncertainty. Ward explains:

“Scientists tend to focus on the interesting questions, which are the areas of uncertainty. But when they communicate in public they should start with what they are quite sure about. If you focus on the uncertainties, people infer that you are uncertain about all of it.”

The Nature editorial makes a similar point, suggesting the way scientists discussed the ‘pause’ in the media contributed to a sense of confusion within the general public. It says:

“The surprise of the slowdown in warming and the subsequent media engagement by scientists, with a focus on uncertainties, leaves the public questioning what is actually known.”

The ‘pause’ in the public consciousness

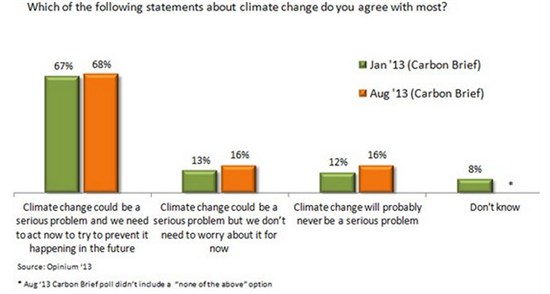

So if the terms ‘pause’, ‘slowdown’ and ‘hiatus’ have appeared more frequently in media coverage, has this influenced the way the public sees climate change? In fact, polling we carried out last year suggests coverage of the pause has not registered strongly in public perception.

Carbon Brief asked respondents which news stories – from a list of real and made-up ones – they could remember hearing. Just one in 20 people recognised “climate change has stopped over the last 16 years” as a story. Reporting on our results, polling expert, Leo Barasi, said:

“[D]espite the attention [the ‘pause’ has] had, almost no-one can remember hearing it”.

Our polling also suggests overall opinion about whether or not to act on climate change didn’t change much between January and August last year, when coverage of the ‘pause’ was at its highest.

It’s worth noting the same may not true worldwide, however. Boykoff highlights US research suggests the proportion of US citizens who believe climate change isn’t happening has increased seven percent since April 2013 – a trend the researchers attribute largely to media coverage of the ‘pause’.

In the UK, what may be more significant is the impact of the ‘pause’ on the political space. Ward suggests:

“[S]ome politicians are using the slowdown to try to justify ideologically driven statements about climate change.”

Soul searching

This would all suggest what we’ve seen in the UK is the so-called ‘pause’ morph from a longstanding scientific question into a media preoccupation – but not necessarily a public one. On the media noise surrounding the ‘pause’, Barasi says:

“[I]t’s important for all of those in the debate to remember that, most of the time, however big your platform is, and however loudly you shout, almost no-one notices or cares as much as you do.”

So while the scientific community’s response to the ‘pause’ as a media story has prompted some intense reflection, the impression from our polling is that the ‘pause’ is less of a public concern than some close to the debate may fear.

It’s right that scientists should seek to better understand and communicate the ‘pause’, and that issues of scientific importance, uncertainty and disagreement shouldn’t be hidden away from the public and policymakers. All of these are very important points the special issue brings to the fore.

Hawkins’s commentary suggests issues like the ‘pause’ could even be a chance to increase public scientific literacy:

“[W]e should see the pause as an opportunity, offering a clear hook to explore exciting aspects of climate science; to draw back the curtain on active scientific discussions that are often invisible to the public.”

But while there are general lessons about communicating climate science to take away from the ‘pause’ experience, the soul searching raises interesting questions about focusing on a single topic in climate science – especially when the available data suggests its impact on public opinion has been minimal. Arguably, there’s a danger such attention could distract from conversations that might move the media discourse further forward.

That said, if the result is enthusiasm and willingness by scientists to engage with the media and the public, that’s a positive thing however you slice it.