Simon Evans

08.09.2014 | 4:30pmThe build up to the 18 September Scottish independence referendum has now officially reached fever pitch. With polling suggesting a vote for independence is a real possibility, the question of how the union might be divided has taken on a new significance.

Scotland and the rest of the UK are closely interdependent for energy infrastructure and fossil fuel resource. So how would the UK divide up its oil, wind and gas resources with an independent Scotland, and what would it mean for each of the new nations’ efforts to decarbonise?

North Sea oil and gas

The largest energy prize in economic terms is North Sea oil and gas. Some 40 billion barrels have been extracted so far and anything from 2 to 24 billion barrels remain, depending who you ask.

The Scottish government says Scotland would have a right to 90 per cent of future North sea oil and gas tax revenues. That’s based on drawing a boundary in the North Sea that is equidistant from the shores of England and Scotland.

This method is called the ‘median line’ or ‘equidistance principle‘. It was used when the UK, Norway and Denmark carved up oil and gas rights in the 1960s, before the North Sea oil rush began.

But since then, a disputed settlement over North Sea rights for Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands concluded the equidistance principle does not have legal weight and other factors can be considered.

The UK government’s review of boundary issues lays out the legal principles that would apply in any settlement. It notes that fisheries boundaries were drawn in 1999 along the line of equidistance, marked in blue on the map below. Civil legal jurisdiction is based on a simple line of latitude, marked in red. This would be more favourable to Scotland.

Source: HM Government ” Scotland analysis: Borders and citizenship“

A Scottish government report uses the blue median line in estimating future shares of oil and gas tax revenues. This very detailed academic review of the legal principles and precedents around maritime borders concludes the line should be pushed further south, in Scotland’s favour.

However, the final boundary would have to be negotiated between an independent Scotland and the rest of the UK.

Relative populations are not a central consideration in maritime boundary disputes, so it seems most likely that the median line would be the starting point for negotiations.

On that basis Scotland would gain the lion’s share of future North Sea tax revenues. Full Fact reports that Scotland would get 84-95 per cent of revenues, according to the Scottish government, or 73-88 per cent according to the HMRC. Both calculations are based on the median line and vary only in their estimates of production and tax rates for the various oil and gas fields.

In 2012/13 an 84 per cent share of North sea tax revenues was worth £5.6 billion. But future revenues are highly uncertain and are dependent on oil prices and the costs of extraction, among other factors.

Can Scotland cut emissions while maximising fossil fuel exploitation? Scottish climate minister Paul Wheelhouse tells RTCC he recognises the question is important, but that there will be demand for oil and gas in the short to medium term. And of course the same question applies whether the UK is divided or not.

Electricity supplies

So much for the fossil fuel. What about the electricity generating capacity?

Scotland’s electricity supplies are much lower-carbon than the rest of the UK’s. In 2012 Scotland got a pretty stunning 69 per cent of its power from a combination of renewables (purple area, below) and nuclear (light blue area).

Source: DECC electricity generation and supply figures for the home nations, 2012

Scotland plans to generate the equivalent of 100 per cent of its electricity from renewables by 2020. It would keep nuclear and conventional power plants open, generating more than 100 per cent of its needs in total and notionally exporting the non-renewable part to England.

Scotland has 43 per cent of the UK’s wind capacity and pumps out 92 per cent of its hydroelectric power, and is set to continue to dominate renewables production on these islands, reflecting its abundant resources of wind and space. DECC saysrenewable energy investments worth £30 billion have been announced in the UK since 2010, of which £14 billion is in Scotland.

Taking the UK as a whole – including Scotland – 12 per cent of our electricity came from renewables in 2012. (The amount has since risen.)

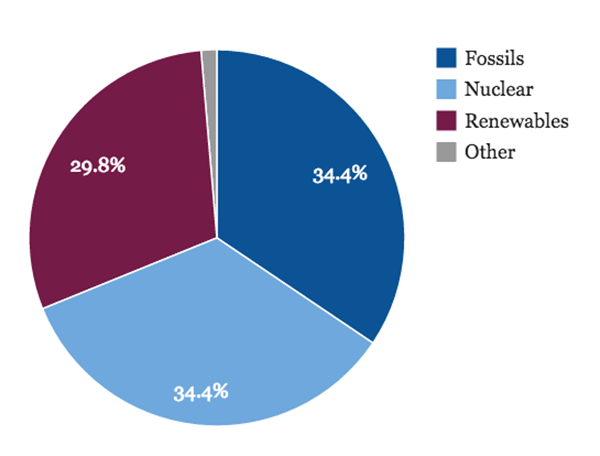

Source: DECC electricity generation and supply figures for the home nations, 2012

If Scotland gained independence, it would make the electricity supply of the rest of the UK less green.

On 2012 figures, the rest of the UK excluding Scotland got only 9 per cent of its power from renewables, and only 17 per cent of electricity from nuclear power.

Source: DECC electricity generation and supply figures for the home nations, 2012

So it might seem like losing Scotland would make it more challenging for the rest of the UK to meet the EU target to source 20 per cent of energy from renewables by 2020.

It isn’t clear how this target would be divvied up if Scotland votes yes. But it’s fair to assume the UK would continue to rely on renewables from north of the border unless the target is amended, post independence.

EU rules allow for the UK to meet its target by importing renewable electricity from other member states, or even to simply buy renewable energy ‘credits’ from countries that have exceeded their target.

The UK government says the rest of the UK could choose not to pay the bill for subsidised renewable power from an independent Scotland. But it couldn’t forego Scottish renewable electricity imports overnight because it needs the power to keep the lights on. Scotland supplies 4.6 per cent of demand in England and Wales.

The UK as a whole is already a net importer of electricity, getting around five per cent of its supplies via interconnector cable mainly from France and the Netherlands. Simon Moore, senior research fellow for energy and environment at right-leaning thinktank Policy Exchange says:

“It would be difficult [for the rest of the UK] to immediately replace all imports of Scottish generation including wind, conventional and hydroelectric power.”

Moore explored the potential for new interconnectors in a June report. Plans to boost interconnector capacity across the channel would allow England to increase imports from the continent a bit, he says, while plans to link up with Norway would further boost potential. But both will take time.

At this stage it is almost impossible to say how the energy systems of Scotland and the rest of the UK would fit together, post independence, although Westminster has had a go.

Moore suggests it might be easier to retain a UK electricity grid than to split 100 years of joint grid investment, for example, but detailed discussions wouldn’t begin until after a yes vote. He concludes: “I don’t think anyone really knows what will happen.”