Robert McSweeney

20.08.2015 | 7:00pmForests around the world are being affected by humans – both directly by deforestation and indirectly by climate change, say experts in a special issue of the journal Science.

In a series of reviews of the latest research into the health of the world’s forests, scientists find they are far from being in the best shape for coping with climate change over this century. And this could affect how well trees absorb and store carbon in the future, they say.

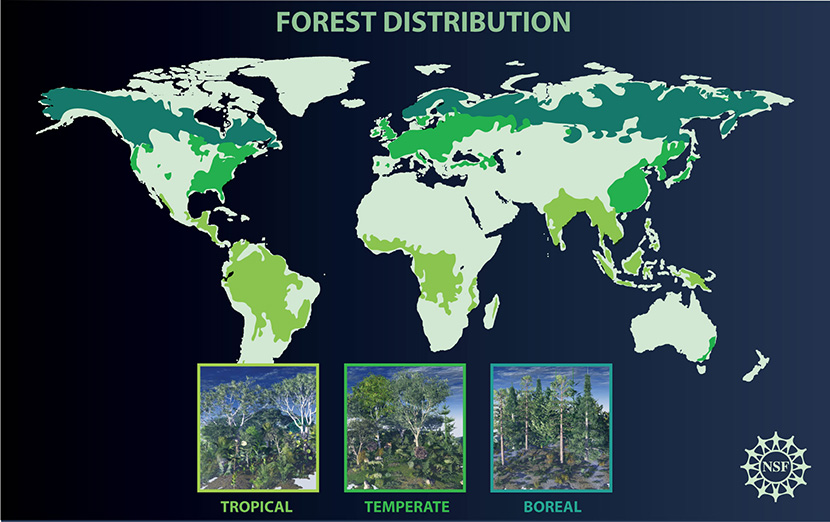

Forest distribution

The world’s forests generally fall into three categories, according to where they’re found. You have the warm, humid conditions of tropical forests around the equator, the mild conditions enjoyed by temperate forests in the mid-latitudes, and the freezing cold of boreal forests in the North.

Global forest distribution. Credit: Nicolle Rager Fuller, National Science Foundation.

Today’s special issue tackles each type in turn. We’ll start with tropical forests, home to half of the world’s species of plants and animals.

Human impacts such as logging and clearance for farmland and mining have left less than a quarter of tropical forests intact, say the authors of one of the special issue papers. The remaining three-quarters are either fragmented or otherwise degraded.

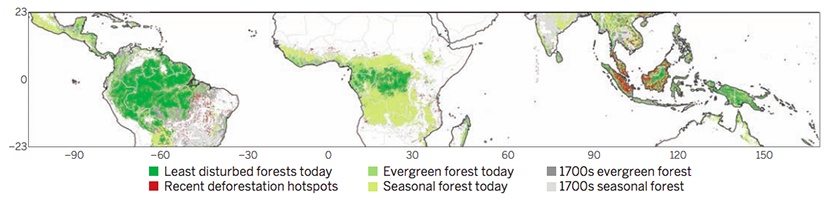

The grey shaded areas in the map below show where forest has been cleared since the 1700s, and the red areas show recent hotspots for deforestation. But through the coming century, the threat of forest clearance will be “increasingly combined with the impacts of rapid climatic changes,” the researchers say.

Map of current and historical year-round (“evergreen”) and seasonal tropical forest extent. Source: Lewis et al. (2015).

Tropical forests

Climate change will have competing impacts on forests, lead author Dr Simon Lewis, from University College London and the University of Leeds, tells Carbon Brief:

At the moment, the balance for tropical forests is towards increasing carbon stocks, says Lewis. Scientists can’t be sure how long this positive effect will last, he adds, as trees will not continue to respond to ever-higher levels of carbon dioxide. A key factor is whether the forests are still standing in order to make the most of this benefit, Lewis points out.

For creatures living in tropical forests, the future is more one-sided, says Lewis:

Some species will be unable to move fast enough to keep up with changes in climate, while deforestation means species may be cut off from migrating to new areas, says Lewis:

Tropical rainforest in Kaeng Krachan, Thailand. Credit: Shutterstock.

Temperate forests

Heading away from the tropics brings us next to temperate forests. Some are deciduous, where the trees lose their leaves in the winter, while the rest are evergreen.

One of the main threats to temperate forests is drought, say the authors of a second paper in the special issue:

These droughts are pushing some temperate forests “beyond thresholds of sustainability”, the researchers say.

Higher temperatures mean more water is evaporated into the atmosphere, leaving less for the trees. In addition, melting snow is often a key source of water for some temperate forests, but warmer conditions mean that snow is now more likely to fall as rain. Without a build-up of snow in winter, there isn’t as much to melt through the summer, resulting in increased water stress for forests, the researchers say.

Studies show an increase in tree deaths from these more severe droughts, while increasing water stress also leaves trees more susceptible to damage by pests, disease and forest fires, the researchers say.

In the short-term, temperate forests may be able to rebound from these impacts, but the longer-term outlook is not so promising, the researchers conclude.

Most temperate forests are likely to change in condition, they say, which could include minor shifts in the number, type and age of trees or “major transformations” in the types of trees that the forests play host to. This could mean current species are outcompeted by more drought-tolerant species or those better able to cope with pests and diseases.

Temperate forest, England. Credit: Shutterstock.

Boreal forests

Lastly, we come to boreal forests. Found in northerly areas just shy of the Arctic circle, boreal forests are made up of mostly evergreen trees such as fir and pine, which can cope with the long, cold winters.

Around two-thirds of boreal forests are managed in some way, usually for wood production, says a third paper of the special issue.

Of all three types of forests, boreal forests are expected to experience the largest rise in temperature over the 21st century, the researchers say. If the world warms by 4C above pre-industrial levels, for example, which is what we can reasonably expect if emissions stay very high, boreal forests could see temperatures rise by as much as 11C.

Warmer conditions could see increases in droughts and forest fires, and also in the geographical range of pests and diseases, the researchers say. These changes may offset any benefits from longer growing season or from higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, they add.

Overall, projections suggest that carbon storage in boreal forests is more likely to decrease than increase or stay the same, the researchers find. This may already be happening, they say:

All three papers point out the importance of forest management in determining how resilient the forests will be to climate change. A combination of both halting deforestation and restoring trees that have been cleared could boost the carbon storage of the world’s forests, as well as boosting the survival chances of the species that live in them.

Snowy boreal forest. Credit: Shutterstock.

Main image: Forest near Southend, England. Credit: Scott Wylie/Flickr.

Lewis, S.L. et al. (2015) Increasing human dominance of tropical forests, Science, doi:10.1126/science.aaa9932; Millar, C.I. and Stephenson, N.L. (2015) Temperate forest health in an era of emerging megadisturbance, Science, doi:10.1126/science.aaa9933 & Gauthier, S. et al. (2015) Boreal forest health and global change, Science, doi:10.1126/science.aaa9092

-

Scientists warn of unprecedented damage to forests across the world. Find out why from @CarbonBrief.