Coffee, cashew and avocado growers will be ‘seriously affected’ by climate change

Giuliana Viglione

01.26.22Giuliana Viglione

26.01.2022 | 7:00pmThe growing range of three economically important crops – avocados, cashews and coffee – will undergo significant shifts under even moderate warming scenarios by 2050, new research shows.

The study, published in PLOS One, examines the climate, soil and land factors that affect the suitability for growing each of the three crops. The researchers then map out how these optimal growing regions could change under three different global-warming scenarios.

For all three crops, they find “both regions of future expansion and contraction” under shifting temperatures and rainfall patterns. But they also note that the area of land they rate “most suitable” for crop-growing in many of the major producing countries will largely shrink in the coming decades.

For example, Brazil – the world’s biggest producer of coffee – is projected to lose nearly 80% of its best growing land for the arabica bean under a moderate warming scenario. The study also warns of large reductions in prime growing land for avocados in the Dominican Republic, Peru and Indonesia, and for cashews in Benin.

As a result, the authors say, adaptation measures, such as different land management approaches and selective breeding, will be necessary in most of these major producing regions.

Mapping suitability

Avocados, cashew nuts and coffee are all high-value cash crops grown predominantly in tropical countries. In addition to their high economic value, these three crops “contribute substantially to the livelihoods of smallholder farmers around the world”, Dr Roman Grüter, an environmental scientist at Zurich University of Applied Sciences, tells Carbon Brief.

Grüter, who led the new work, adds that long-term planning is “especially important” for plants such as these, which are perennial crops and can take several years to reach maturity.

In 2019, the world produced about 7.1m tonnes of avocados, 3.8m tonnes of cashew nuts and 10.0m tonnes of unroasted coffee beans, according to statistics compiled by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. The gross production value of the 2019 harvests in 2014-16 international dollars was, respectively, I$6.6bn, I$3.7bn and I$21.0bn. (Data from the International Coffee Organization show that about 60% of the world’s coffee crop is coffee arabica, the species analysed in this study.)

The researchers focused on the four main producing countries of each crop. Brazil, Vietnam, Indonesia and Colombia together produce 64% of the world’s total coffee, although Vietnam and Indonesia predominantly produce coffee robusta, not arabica.

Taken together, Vietnam, India, Côte d’Ivoire and Benin are responsible for 73% of global cashew production. And Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Peru and Indonesia account for 58% of the world’s avocado crop.

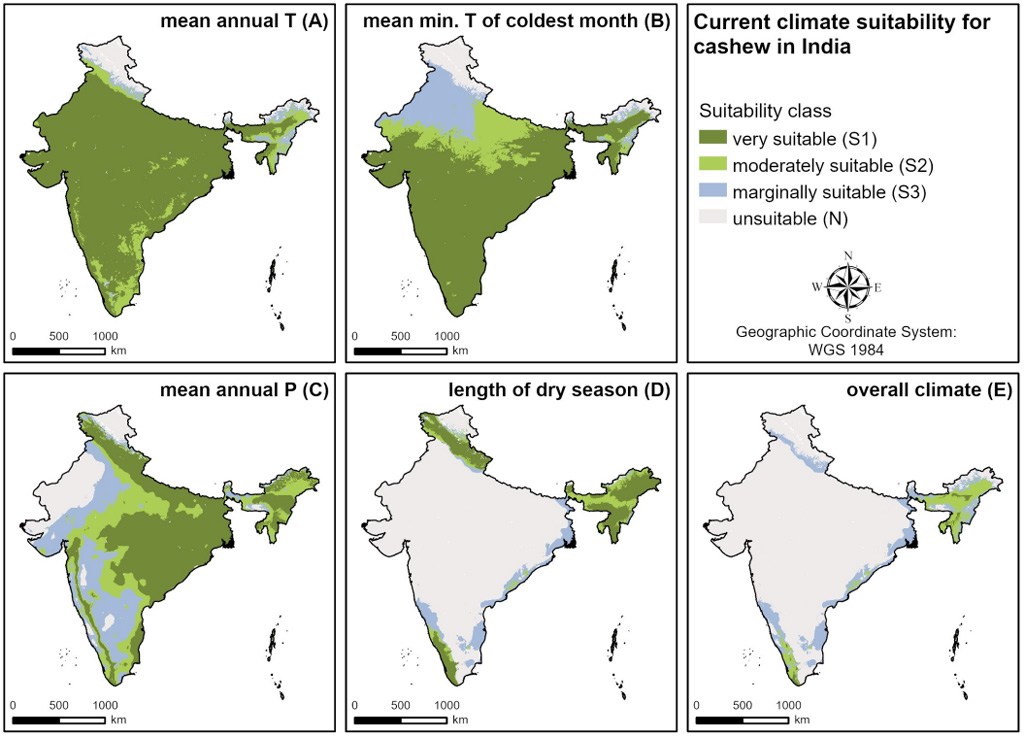

The researchers analysed the existing literature for climate variables and land and soil characteristics that lend themselves to growing each crop, including average annual temperature and rainfall, length of the dry season, soil pH and the slope of the growing land. Each factor was classified along a four-point scale from “unsuitable” to “very suitable” for producing a particular crop.

By combining global maps of all of these variables and taking the lowest-suitability classification for each pixel, Grüter and his colleagues charted out the current suitability for growing each crop around the world, rating locations on that same four-point scale.

The maps below show how each of four climate variables affects the suitability for cashew-growing in India; the resulting composite (in the bottom right-hand corner) shows the overall suitability.

To understand how the changing climate will impact the growing regions for these crops, the researchers used 14 global climate models from the CMIP5 suite of models from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project.

They projected future climate variables across the world under each of three different scenarios: RCP2.6, RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 – representing, respectively, a low-emissions scenario, a moderate-emissions scenario that roughly matches the world’s current trajectory and a very high-emissions scenario.

By recreating the suitability maps using the projected future climate, they could then map out how potential growing ranges would change under each scenario.

Breaking down the suitability into four classifications is “slightly more granular” than previous work, much of which has used a binary classification of suitable/not suitable, says Dr Jarrod Kath, an agroecologist and climate scientist at the University of Southern Queensland who was not involved in the study. Even better, he says, would be to use crop yield to define suitability. He tells Carbon Brief:

“You’re taking a continuous variable like yield and you’re breaking it up into three classes. And so, as soon as you do that, you reduce the amount of information there.”

Future work would ideally take this approach, Kath says. But for now, he adds, the data to do so is “lacking”.

‘Expansions and contractions’

Each crop had “both expansions and contractions” in its suitable growing range, Grüter tells Carbon Brief. For all three crops, he says, “negative climate change impacts on crop suitability have to be expected in some of the main producing countries”.

Coffee was the hardest-hit crop of the three, the researchers found.

Under a moderate warming scenario, the global area falling into the highest suitability class is projected to decrease by more than half compared to 2000 levels. In some of the main producing countries, the effect was even more pronounced: Brazil is projected to lose nearly 80% of its most-suitable land.

The maps below show the change in suitability class for coffee-growing around the world under the RCP4.5 scenario. Green shading indicates improved suitability, while red shows declining suitability.

The current suitability of coffee-growing is determined by a number of factors, depending on the growing location. For example, average annual temperatures that are too high, minimum temperatures that are too low, too much rainfall and even soil that is too acidic can all make coffee-growing a non-starter.

But the projected future decreases in suitability are mainly due to increasing average annual temperatures, the researchers found. They note that “a few” regions to the north and south of the current range “are expected to profit” from these changes.

Avocados and cashews

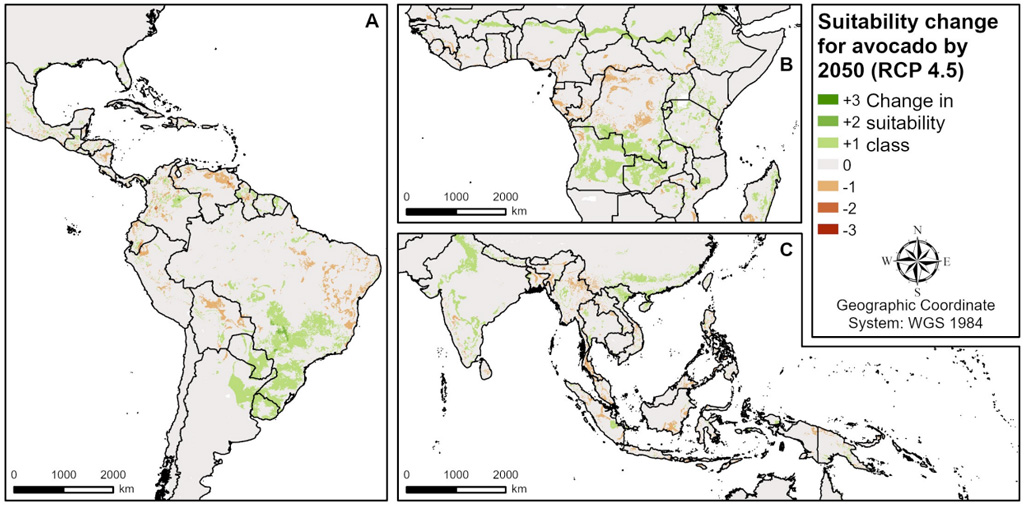

For avocado plantations, the story is more mixed. While there is a global reduction of high-suitability land of about 20% under the moderate warming scenario, not all of today’s high-producing countries will be negatively impacted.

The maps below show where the changes in avocado-growing suitability will occur by the year 2050 under the RCP4.5 scenario.

Mexico, for example, will increase its highly suitable growing land by more than 70%. However, the other major growing nations examined in the study – the Dominican Republic, Peru and Indonesia – will all lose between 55% and 70% of their prime avocado-growing area.

Current avocado production is limited by average minimum temperatures and annual rainfall – the crop “has a narrow precipitation optimum”, the authors write, so both too-wet and too-dry climates are incompatible with avocado growth.

As minimum cold temperatures increase, the model shows expansion of growing areas at both the northern and southern borders of the current range. In some parts of the world, such as sub-Saharan Africa, avocado-growing may also benefit from increasing rainfall. Negative impacts on avocado suitability are mainly explained by changes in rainfall – either increased and decreased, depending on the location.

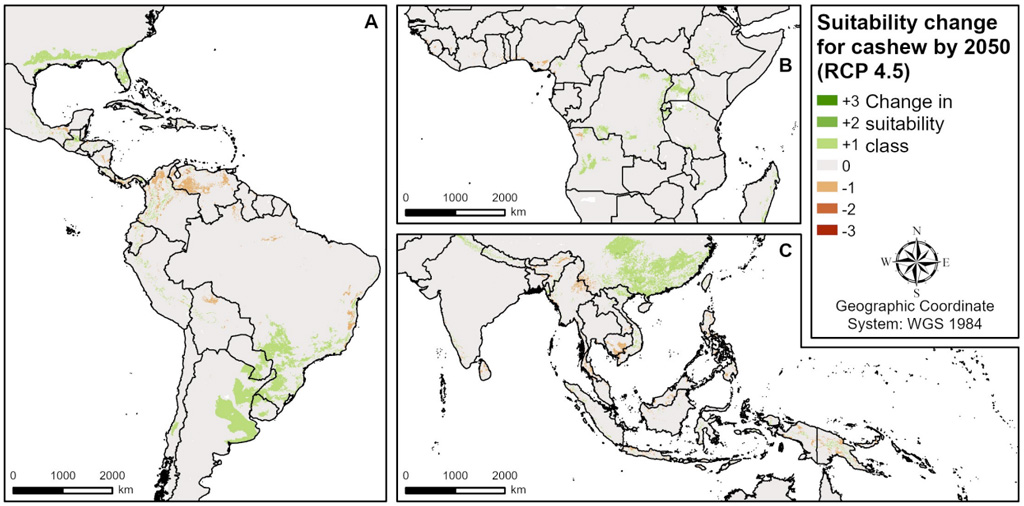

Optimal growing area for cashews will actually increase globally by about 19% by 2050 under RCP4.5, the study finds. Vietnam in particular would see its high-suitability land area increase by about one-third in this scenario. The other major growers of cashew would not fare so well – a 16% reduction for Côte d’Ivoire, a 29% reduction for India and a 78% reduction for Benin.

The maps below show how global growing suitability will change for cashews by 2050 under a moderate warming scenario.

Cashew-growing is currently most heavily limited by the length of the dry season and low temperatures. Much of the expansion of suitable land is due to rising minimum temperatures, although regions such as east Africa and Australia also benefit from increases in the annual average temperature.

The negative effects felt by central and South America, west Africa and south and southeast Asia are primarily due to those same increasing average temperatures. In a few places, increased annual rainfall is also projected to harm the cashew crop.

Adaptation and mitigation

The study was “well-written and well done”, Dr Christian Bunn, an agricultural economist at the Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture, tells Carbon Brief. At the same time, Bunn – who was not involved in the study – adds, “I struggle to see new insights for coffee”.

Bunn notes – as does the paper – that the study’s results are largely in line with what he and his colleagues found in a 2015 study published in Climatic Change that looked at both arabica and robusta coffee. He calls it a “bit of an odd choice” for the researchers to have left robusta out of the analysis.

Kath agrees that the results for the coffee portion of the paper are unsurprising. He tells Carbon Brief:

“You could argue it’s not super novel from the perspective of coffee…It’s pretty well known that coffee is, amongst the important plant species we grow, exceptionally sensitive to changes in climatic conditions.”

However, Kath adds, the literature on cashew- and avocado-growing is much more sparse. “That’s probably where the novelty in the paper is”, he says.

That said, the paper’s findings on avocados are largely in line with previous work as well, says Dr Joaquín Ramírez Gil, an agricultural scientist at the National University of Colombia. Ramírez Gil was a reviewer of the new paper but was not involved in the study itself.

Ramírez Gil’s work on avocados used “different approaches [but] found similar results”, he tells Carbon Brief – both in terms of projected future areas of expansion and the limiting factors for future avocado-growing. His work has focused on avocado suitability in the Americas, whereas the new study takes a global approach.

Grüter tells Carbon Brief that the choice of crops – from a well-studied system like coffee to a less-studied crop like cashews – was designed so the team could evaluate and compare their modelling approach.

This type of study is “very, very important”, says Ramírez Gil. He says that this kind of information is “necessary” for governments and producers alike to be able to make sound decisions about growing in the future. He tells Carbon Brief:

“In my country, every day the avocado crop is increased – the area planted with avocado crops is increasing, increasing, increasing. And many of these crops are planted in an area where the conditions are not suitable and the climate and environmental conditions are no good.”

Ramírez Gil stresses that policies need to be designed with this kind of work in mind, and that scientists need to better communicate their results to governments and other parties.

These results and others show that adaptation in the coffee sector is an urgent matter – and one that will take a “massive effort”, Bunn says. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Changing varieties or changing species is really hard to do, because you have this long lead time…If you want to grow for 2050, you need to plant a shade tree right now so that it is there in 10 or 20 years. You can’t plant it in 10 years, you need to plant it now.”

If adaptation measures are not taken, Bunn says, coffee farmers may be forced off their lands. These areas would likely then be planted with “field crops”, which have much less carbon storage potential than coffee does. And coffee production would move into new areas, which would likely contribute to deforestation. He tells Carbon Brief:

“In coffee production, adaptation goes a great deal towards emissions mitigation, because coffee farms are high carbon-stock systems…In the coffee sector, adaptation is the ethical thing to do, it’s the climate action, the mitigation thing to do. And at the same time, there needs to be investments so that we don’t go down the alternative scenario.”

Grüter, R. et al. (2022) Expected global suitability of coffee, cashew and avocado due to climate change, PLOS One, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0261976

-

Coffee, cashew and avocado growers will be ‘seriously affected’ by climate change