Q&A: Why deals at COP28 to ‘triple renewables’ and ‘double efficiency’ are crucial for 1.5C

Dave Jones

11.21.23

Dave Jones

21.11.2023 | 4:04pmCOP28 president Sultan Al Jaber has urged governments to agree on global goals to triple renewables capacity and double the rate of energy efficiency improvements by 2030.

This call from Al-Jaber is supported by the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), and political momentum is building.

This month, a US-China joint statement on climate change backed tripling renewables to substitute coal, oil and gas power and bring about “post-peaking meaningful absolute power sector emission reduction”.

The context for these targets is a world that remains dramatically off course against global climate goals, with recent assessments pointing to warming of 2.4-2.7C above pre-industrial levels by 2100.

In its recent report on how to get back on track, the IEA said tripling renewables, doubling efficiency and slashing methane emissions 75% by 2030 would provide 80% of the emissions cuts needed for 1.5C.

This Q&A explains what tripling renewables and doubling energy efficiency means – and why they are the two biggest actions the world can take to get back on track for 1.5C, even though they would be insufficient on their own to meet the target.

It also looks at what governments would need to do to deliver these goals and the likelihood of them being agreed at COP28.

- Why are tripling renewables and doubling efficiency key to 1.5C?

- What does ‘tripling renewables’ mean?

- What does ‘doubling energy efficiency’ mean?

- Is tripling renewables possible?

- What would governments need to do?

- The road to COP

Why are tripling renewables and doubling efficiency key to 1.5C?

In the IEA’s latest pathway to keeping warming below 1.5C, global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from energy use fall by 35% by 2030, compared to 2022.

Yet the latest analysis from UN Climate Change (UNFCCC) shows that global emissions are set to fall by just 2% below 2019 levels by 2030, if countries continue to follow their current pledges.

The IEA set out five “pillars” to achieve deep emissions reductions by 2030 and keep the path to 1.5C open, which it suggests should be adopted at COP28. It states that tripling of global renewable capacity is the “single largest driver” of emissions reductions to 2030 in its roadmap.

The other pillars are doubling the rate of global energy efficiency improvements by 2030, cutting methane emissions from fossil fuel production 75% by the same date, developing “innovative, large-scale financing mechanisms” to support such changes in developing countries and measures to ensure an “orderly decline in the use of fossil fuel”, such as no new coal power being approved.

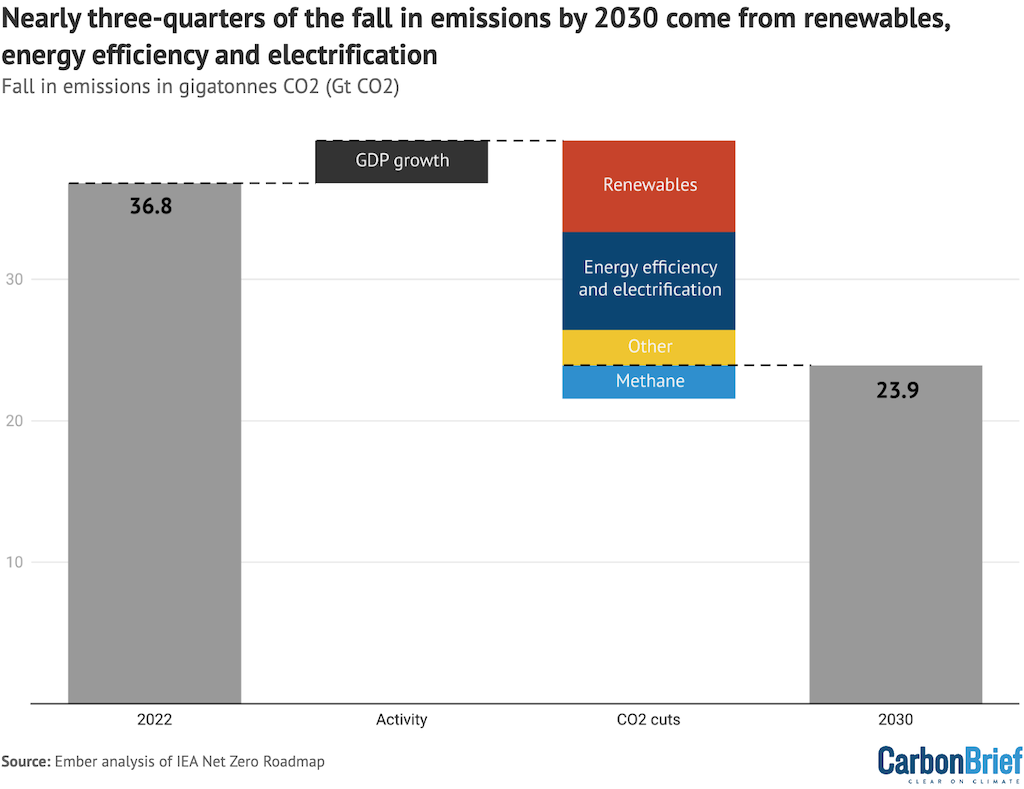

As the chart below shows, renewables growth and improved energy efficiency account for almost three-quarters (72%) of the total CO2 emissions cuts needed by 2030 in the IEA pathway.

Although tripling renewables is the single largest, energy efficiency – when combined with electrification – makes a slightly larger contribution.

The next largest contribution in the IEA’s roadmap would come from slashing the amount of methane released during the extraction of fossil fuels.

The leftmost column in the chart below shows global energy-related CO2 emissions in 2022. The black wedge shows how this would be expected to increase out to 2030 as a result of economic growth.

The next wedges show how expanding renewables (red), boosting energy efficiency (dark blue) and other mitigation measures (yellow) would cut emissions by 2030. The light blue wedge shows the additional contribution to cutting greenhouse gas emissions from tackling methane.

Renewables would in fact have a hand in both doubling efficiency and slashing methane emissions. Renewables would help to power emissions savings from electric cars and heat pumps, which are both counted in the “efficiency” wedge because they are much more efficient than petrol cars and gas boilers.

Furthermore, tripling renewables would halve the need for coal power, which would in turn deliver almost half of the reduction in coal mine methane required under the IEA’s 1.5C pathway.

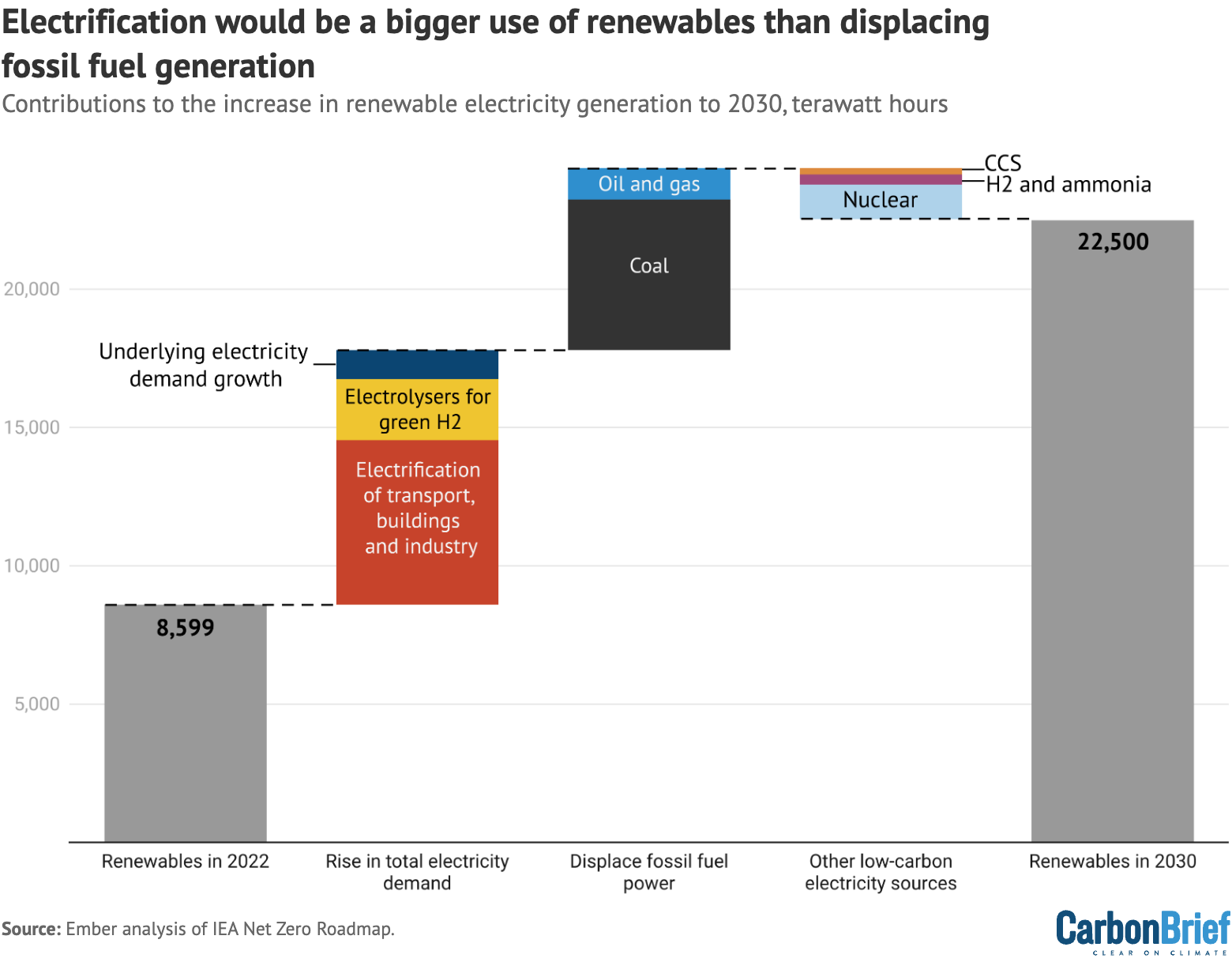

Ember’s analysis of the IEA’s 1.5C pathway, shown in the chart below, finds that just under half of the increase in renewable generation to 2030 would be used to displace fossil fuel electricity, while just over half would be used to meet rising electricity demand.

The large majority of the rise in electricity demand to 2030 would come from electrifying buildings, transport and industry. Another sizable part of the rise in electricity demand would power electrolysers to manufacture “green hydrogen”.

The leftmost column shows global renewable electricity generation in 2022. The second set of wedges shows increases in demand due to electrification (red), production of green hydrogen (yellow) and underlying electricity demand growth (dark blue).

The third set shows the displacement of electricity generated from coal (black), as well as oil and gas (light blue). The final wedges show contributions from other low-carbon sources, including nuclear (sky blue), hydrogen or ammonia (purple) and fossil fuels with carbon capture and storage (orange). The rightmost column shows electricity generation from renewables in 2030 under the IEA pathway.

The chart above also illustrates why energy efficiency improvements are also critical. Without efficiency, total electricity demand would rise substantially faster, meaning there would be much less additional renewable power to displace coal and gas-fired generation.

What does ‘tripling renewables’ mean?

The target of tripling renewable energy capacity by 2030 was not initially clearly defined, with different groups and different pathways implying slightly different goals.

The COP28 presidency is now explicitly calling for a target of 11,000 gigawatts (GW) of renewable capacity by 2030, which would mean a tripling of the 3,629GW installed by the end of 2022.

This target is similar to the levels installed by 2030 in 1.5C pathways from the IEA and IRENA, which reach 11,008GW and 11,174GW respectively.

A global tripling would not mean every country being required to achieve a tripling of domestic capacity. Each country’s renewable capacity today affects how ambitious it would be to individually achieve a tripling – and the target is defined at a global level, rather than nationally.

With this in mind the Nairobi Declaration for example, targets a fivefold increase in Africa’s renewables capacity, subject to access to financing.

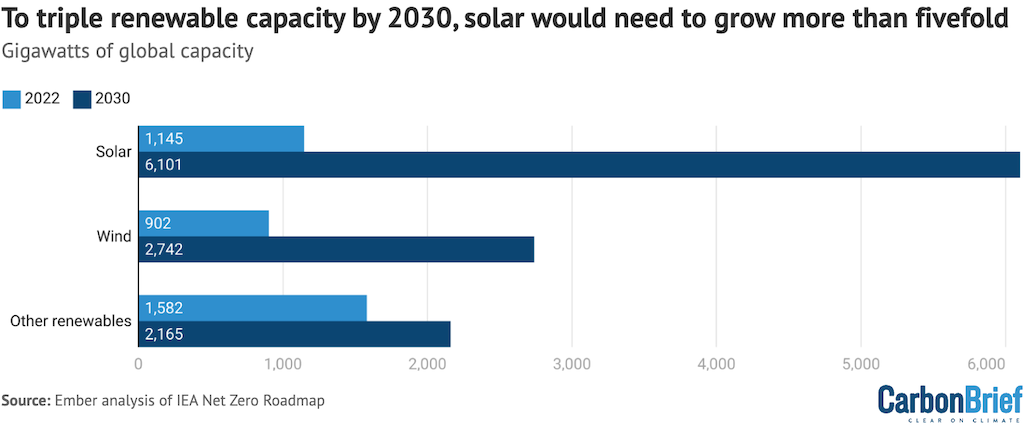

Solar is expected to be the main technology used for tripling capacity. It provides two-thirds of the rise in renewables capacity out to 2030 and half of the increase in generation in the IEA’s 1.5C scenario.

This would see solar capacity increasing fivefold from 2022-2030. Combined with a threefold increase in wind , wind and solar would provide 92% of the tripling target.

New hydro, bioenergy, geothermal, marine and other technologies are still significant though, accounting for 8% of new renewable capacity and 15% of the rise in renewable generation.

The figure below shows the increase in capacity expected from solar, wind and other renewables under the IEA’s 1.5C pathway, illustrating the dominant role of wind and solar.

New nuclear and, to a lesser extent, fossil-fired generation with carbon capture and storage, have a much smaller role to play in 2030 under the IEA’s 1.5C pathway.

The increase in global nuclear capacity increase by 2030 would be equivalent to just 2% of that for renewables – though this would be equivalent to 9% of the rise in renewables generation.

What does ‘doubling energy efficiency’ mean?

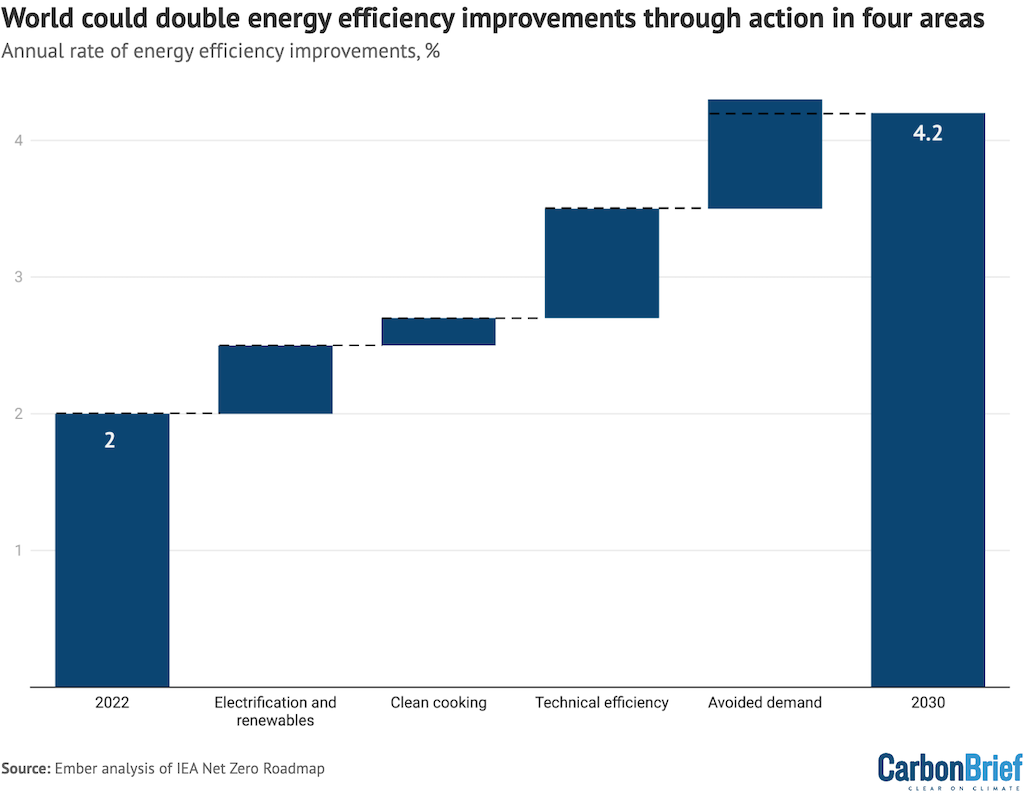

The proposed target of doubling energy efficiency is a shorthand for saying that the rate of energy efficiency improvements would need to double by 2030, compared with 2022 levels.

Specifically, as proposed by the IEA, the target refers to the rate of improvement of global energy intensity, the amount of energy needed to generate each unit of economic output.

This stood at 2% per year in 2022 – already nearly double the average rate of the previous five years, according to the IEA. In the IEA’s 1.5C pathway, this rate continues to rise, reaching 4% per year in 2030.

According to the IEA, doubling the rate of energy efficiency improvements could be achieved through four pillars, shown in the chart below.

First, electrification and renewables. Electric vehicles use two-to-four times less energy than internal combustion engine vehicles; meanwhile, heat pumps use three-to-five times less energy than fossil fuel boilers. Moving to a more electrified economy would substantially reduce overall energy demand.

Second, clean cooking. Traditional use of biomass is extremely inefficient compared to modern improved cooking stoves. Over two billion people today lack access to clean cooking, and the IEA assumes this falls to zero by 2030 in its 1.5C pathway.

Third, technical efficiency. Focusing on the best available technologies for all electrical appliances, especially air conditioners, makes for the largest increase in efficiency of all the pillars.

Fourth, behavioural changes by individuals. The IEA makes relatively stretching assumptions here, including on heating and cooling homes less, reducing demand for flights and shifting surface transport away from cars.

Energy demand globally has been consistently increasing – but at a slower rate than GDP. This has resulted in large gains in energy intensity over at least the last half-century.

However, the IEA net-zero scenario shows that to stay below 1.5C, the world would need to do something new: reduce primary energy demand, even as GDP rises.

Achieving the rise in energy intensity to 4% per year would mean global primary energy demand in 2030 would be nearly 10% lower than in 2022.

Crucially, however, greater energy efficiency would mean the world could generate higher levels of energy services – warm homes, miles driven and so on – even as primary energy demand falls.

Is tripling renewables possible?

While tripling renewable energy capacity in just eight years might seem like an impossibly ambitious target, it’s worth reflecting on progress to date.

According to IEA figures, global renewable energy capacity reached 3,629GW in 2022, nearly triple the level seen in 2010. Moreover, within that total, solar capacity increased 29-fold.

(IRENA figures, reflected in the figure below, record a slightly lower total of 3,372GW.)

Both the IEA and IRENA’s modelling on what it would take to stay below 1.5C include renewable capacity tripling to at least 11,000GW by 2030. While the scenarios do not test what is possible, they are based on the agencies’ assessments of what it would be reasonable to achieve, in each country and sector of the global economy.

Another way to answer the question of whether the tripling target is possible is to look at current government plans to expand renewable energy capacity.

An analysis by Ember of 57 country-level renewable policies for 2030, covering 90% of global electricity generation, shows that the world is already targeting more than a doubling of renewable capacity to 7,250GW by 2030.

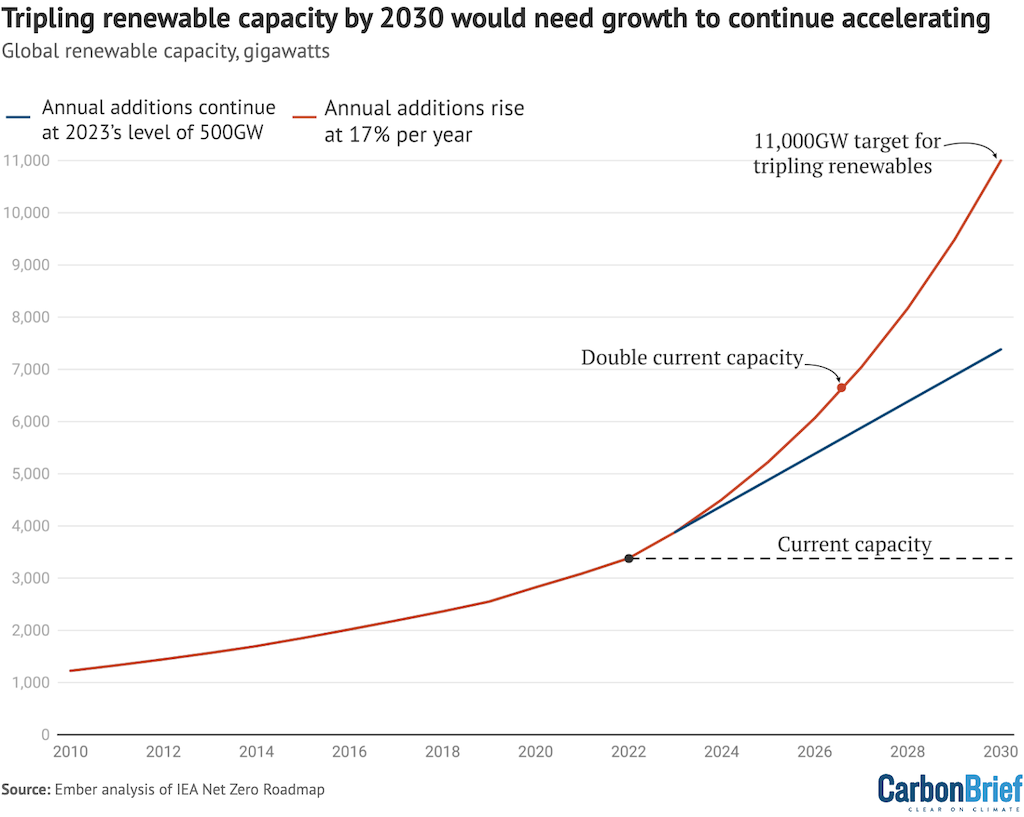

This would be roughly equivalent to repeating the record annual additions expected in 2023 – some 500GW, up from 300GW last year – every year for the rest of the decade, as shown in the figure below.

Still, tripling renewable capacity within eight years would require even more rapid growth, as the chart illustrates. Annual additions would need to rise from 500GW in 2023 to 1,500GW in 2030, an annual growth rate of 17%. It is worth adding that the average growth rate from 2016-2023 was also 17%.

The latest IEA assessment of government policies is more optimistic than Ember’s, showing global renewable capacity reaching 8,611GW by 2030 or 9,786GW if countries meet their climate pledges.

Moreover, Ember’s country-level analysis highlights that many national targets were set before the record renewable progress in 2023, meaning their ambition is perhaps lower than it could be.

Nevertheless, it is clear that a tripling target would entail significantly higher ambition than governments are currently envisaging.

What would governments need to do?

Tripling renewables and doubling energy efficiency is achievable, according to a recent flagship report by IRENA, the COP28 presidency and the Global Renewables Alliance.

However, meeting the targets would require significant effort at a national and international level, the report says. It identifies the key enablers to unlock a large-scale increase in renewables and energy efficiency through decisive action from policymakers.

The policy priorities in the report include: standards for new appliances and buildings or bans on the least efficient options; reform of tax incentives and subsidy reform, including of direct and indirect fossil fuel subsidies; electricity market redesign, recognising the shift towards systems largely based on zero marginal cost renewables; streamlined permitting, particularly for wind, solar and electricity networks; and efforts to maximise social benefits, via community benefit schemes and other measures.

These policy interventions are needed across the whole of government – not just the climate and energy ministries – according to the report, meaning their implementation would require supporting all government departments to deliver the energy transition.

Expanding low-carbon energy sources in line with the tripling target relies on a fast build-out of new infrastructure. This includes building power grids faster, developing more energy storage, and ensuring smart electrification. In many countries, electricity grids are holding back not just the deployment of renewables, but also the connection of electric cars and heat pumps.

Energy storage will be a key flexibility measure, the report continues, and long-duration storage is highlighted as a major priority, although flexibility would need to be improved everywhere. For example, it highlights that electrification would need to be “smart” so that electric cars and heat pumps are used most when there is abundant sun and wind.

Finally, finance support is critical, the report says. Only 20% of renewables investment happens outside China and developed economies, with access to competitive finance being a major barrier.

The IEA suggests $80-100bn in annual concessional funding is needed by the early 2030s to lower the cost of finance and mobilise private capital in lower income countries.

Andreas Sieber, of environmental NGDO 350.org, suggests that even more funding would be required, suggesting debt cancellation at scale, as well as $100bn in concessional finance and $200bn in grants yearly.

The road to COP

Support for the targets of tripling renewables and doubling energy efficiency is building ahead of COP28, but many hurdles remain.

More than 60 countries, including the EU, US and COP28 hosts the UAE have now said they would support a pledge to triple global renewables, a draft of which would also commit to doubling efficiency.

However, this would have a different status to a deal backed by all countries within the final COP28 text.

The recent US-China climate statement committed both countries to support a global tripling of renewables, but overlooked a doubling of energy efficiency, mirroring the G20 position. It remains to be seen if the agreement reached at COP will include either target.

If the targets are agreed, there would also be a need for action to meet them.

The COP presidency is already urging countries to come to COP with “tangible commitments” to achieve the renewable and efficiency goals. After that, a post-COP review process would deliver accountability for the achievement of the targets.

Beyond the renewable and efficiency targets, COP28 is likely to be debating text in other related areas, including whether to phase down or phase out fossil fuels.

As the charts above show, delivering on renewables and efficiency would yield major reductions in fossil fuel use this decade. However, they are only two parts of the IEA’s recipe for staying below 1.5C.

As IEA executive director Dr Fatih Birol told Carbon Brief in September, implementing some but not all of those ingredients would not be sufficient to get back on track.

In particular, Birol noted the importance of “giving a signal to the markets and the governments and companies around the world that in order to reach this 1.5C target, we have to see fossil-fuel use decline”. A target on renewables alone would be “far from being enough” for 1.5C, he said.

-

Q&A: Why deals at COP28 to ‘triple renewables’ and ‘double efficiency’ are crucial for 1.5C