Q&A: What next for UK capacity market after surprise EU ruling?

Simon Evans

11.22.18Simon Evans

22.11.2018 | 4:37pmThe UK capacity market, the main government policy for “keeping the lights on”, has been rendered illegal after a surprise EU court ruling issued on 15 November.

The market is a key plank of the government’s 2013 “Electricity Market Reform” (EMR), designed to decarbonise UK electricity supplies while maintain security of supply and minimising costs. Nearly £6bn of capacity contracts had been handed out, mainly to old coal, gas and nuclear plants.

The market was approved in a 2014 decision by the European Commission, which said it complied with rules on “state aid”. In its recent ruling, the General Court of the EU annulled this approval and said the commission should have opened a more detailed formal investigation into the market design.

Since the ruling, the capacity market has been put on hold. This means that no payments will be made to power firms, including under contracts for this winter worth around £1bn. It also means the next capacity auctions are indefinitely postponed. They were due to be held in January 2019.

The UK government says the ruling was “procedural”. It will seek to have the market re-approved as soon as possible. Tempus Energy, which won the ruling after a four-year court battle, says the market will have to be reformed to allow greater access for “cheaper, cleaner alternatives”.

Simon Virley, partner and head of energy at consultants KPMG tells Carbon Brief: “This is much more significant than just a ‘procedural matter’ as [secretary of state] Greg Clark insisted last week.” Virley led the EMR team at the then-Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC).

It could take “as long as 20 months” to resuscitate the capacity market, another expert tells Carbon Brief. Both say power plants are unlikely to close this winter, despite the ruling. But some of the UK’s six large coal sites could then close earlier than expected, along with some older gas stations.

The UK is set to leave the EU well before this issue is resolved, adding another layer of uncertainty to the process. Capacity markets in France, Italy, Poland and the island of Ireland were given EU approval after the UK scheme and seem unlikely to be affected by the ruling, at least initially.

What is the capacity market?

The capacity market is designed to make sure there is always enough supply to meet peak electricity demand, even on cold and dark winter evenings when there is little wind. It covers the electricity market in Great Britain only, with Northern Ireland part of an all-Ireland scheme.

It awards contracts to firms that offer to supply electricity generating capacity during the periods of peak demand between 4pm and 6pm in winter. Firms can offer to turn down electricity demand instead – a process called demand-side response (DSR).

Existing power plants can get contracts for one year at a time, or three years, if they carry out upgrades. New power plants get 15-year deals. Crucially, DSR is only offered one-year contracts. This is why Tempus Energy – a DSR firm – challenged the capacity market approval.

The contracts are handed to the lowest bidder in a series of auctions. The amount of capacity bought in the auction is decided in advance by government, based on advice from the electricity system operator National Grid.

![]()

The main auction is called T-4 because it is held four years in advance. This allows new power stations time to be built. A smaller second auction is held one year ahead (T-1) to fill in any gaps. The T-1 auction is also designed to reserve some capacity for DSR.

The capacity market was one of two key measures in the 2013 “Electricity Market Reform” (EMR). The other was contracts for difference (CfDs) to support low-carbon electricity generation.

Does the UK need a capacity market?

The capacity market aims to solve what is called the “missing money problem”. Put simply, this is the idea that the wholesale electricity market fails to give sufficient incentives to utilities to build new power plants or, in some cases, to keep old plants open until the end of their useful life.

The money they would need to do so is “missing” for several reasons. One is that subsidised low-carbon sources generate electricity at near-zero marginal cost, depressing wholesale prices. Another is that regulators tend to cap the level that prices can reach when supplies are tight.

Conventional thinking says that, without a solution to this problem, there is a risk that demand would exceed supply, leading to blackouts. Before the 2014 approval, the UK government successfully persuaded the European Commission that the capacity market was needed to prevent such a risk.

The capacity market also addresses a political problem. Prior to its introduction, an autumn ritual saw newspapers headlines suggest the UK’s lights “could go out” or warning of “blackouts”.

These articles – since proven inaccurate – tended to focus on the UK’s shrinking “capacity margin”, the buffer between expected peak demand and available supply. This winter, that margin grew to nearly 12%. Power plants threatening to close also used to prompt frequent headlines.

Since the capacity market was introduced in 2014, these headlines have dried up and public concern over blackouts has eased.

“Blackout” headlines have really dried up since the UK capacity market was introduced in 2014.

What happens now it’s been ruled illegal?

Source: Factiva search of key UK media for “blackouts electricity”. pic.twitter.com/co7KmX07K8

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) November 21, 2018

Are there alternatives to a capacity market?

Critics argue the UK never needed a capacity market and that it was a politically driven project to deliver large new gas-fired power stations, which have not materialised and were also not needed.

These critics say capacity needs have been systematically overestimated by an average of 1.5 gigawatts (GW), equivalent to a large coal or gas plant – and that a “strategic reserve” would be cheaper. This would hold a few power plants in reserve in case the market failed to deliver.

The capacity market has also mostly awarded contracts to large old power plants, including the coal-fired power stations that the government wants to close by 2025. This means government policies are pulling in opposite directions – supporting coal, but also encouraging it to close.

Others point out that the market has nevertheless brought forward a lot of new capacity. Carbon Brief analysis of capacity market results shows that nearly 4GW of small new flexible gas- and diesel-fired “peakers” have won contracts to date, as well as around 1GW of battery storage.

[The government acted to limit the number of “dirty diesel” peakers through changes to air pollution rules, after large numbers won contracts in early capacity market auctions.]

A series of parallel policy changes mean it is hard to be sure that these projects would not have happened without the capacity market. These include “cash out” reforms designed to allow peak power prices to climb higher, encouraging generators to provide enough supplies to meet demand.

Another is National Grid’s “enhanced frequency response” auction, which contracted 0.5GW of batteries to help manage the frequency of electricity supplies. These batteries may also have secured capacity market contracts, allowing them to “revenue stack” different sources of income.

All this makes it hard to isolate the effects of the capacity market alone. For similar reasons, the immediate impacts of the EU court ruling are also likely to be complex, see below for more.

What capacity contracts have been awarded?

In total, contracts worth £5.6bn have been awarded under the capacity market so far since 2014. This has been spread through a number of T-4 and T-1 auctions, as well as several one-off rounds covering each winter from 2016/17 through to 2021/22.

Some of this money has already been paid out. DSR and peaking plant have received £22m in 2016/17 and £14m in 2017/18, under small “transitional arrangement” auctions. A much larger “supplementary” 2017/18 auction, approved separately by the commission, paid £378m for 54GW.

This winter, the T-4 auction for 49GW of capacity and T-1 contracts for 6GW were set to see payouts just shy of £1bn. This money will not be paid while the capacity market remains on hold.

Capacity market prices peaked in the 2016 T-4 auction for 2020/21, which cleared at £22.50 per kilowatt (kW). This fell to £8.90/kW in the T-4 for 2021/22. The T-1 rounds have been even cheaper, at £6/kW for this winter and £6.95/kW for a supplementary auction covering winter 2017/18.

In general, prices have come in far lower than expected. This means either that there was a larger pool of available capacity than thought – and, hence, little need for the market – or that the auctions have delivered security of supply so efficiently as to keep costs low for consumers.

Most contracts so far have gone to large old power stations. Coal, gas and nuclear plants have taken nearly three-quarters of contracts and gas makes up around half of contracted capacity.

This means the scheme would have paid large sums to these old plants if it had continued – or if it is re-approved without changes. A 2GW coal plant – for example, Cottam in Nottinghamshire – would have received around £40m in payments this winter and a similar sum next year.

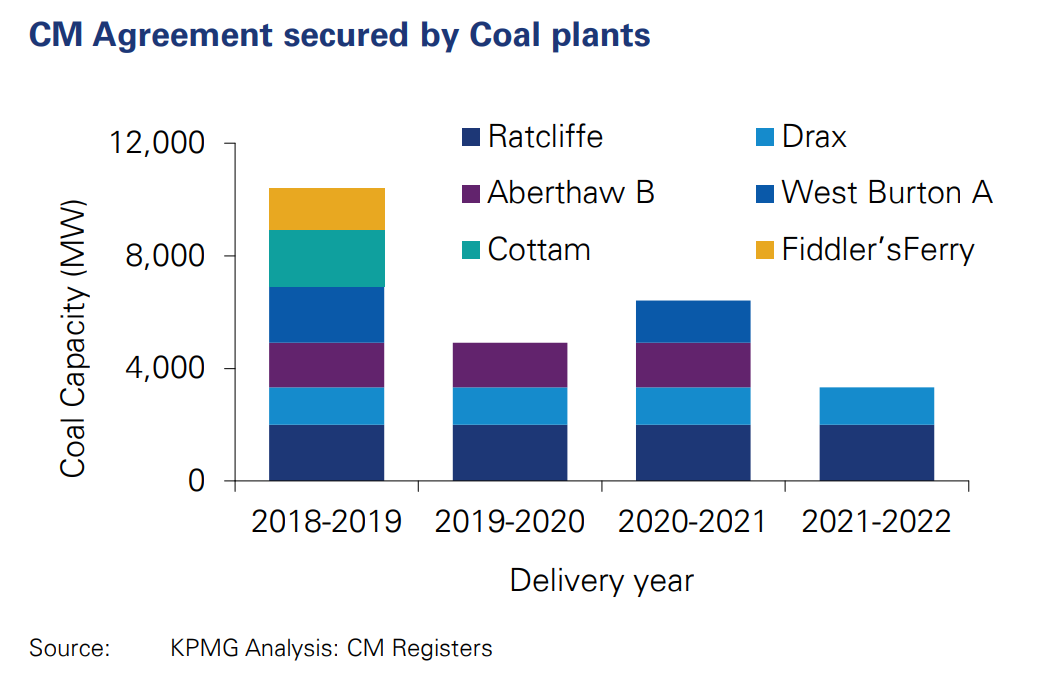

However, the number of coal plants winning contracts has fallen over time, as the chart below shows.

Coal capacity winning capacity market agreements in each of the main auction rounds held so far, megawatts (MW). Source: KPMG.

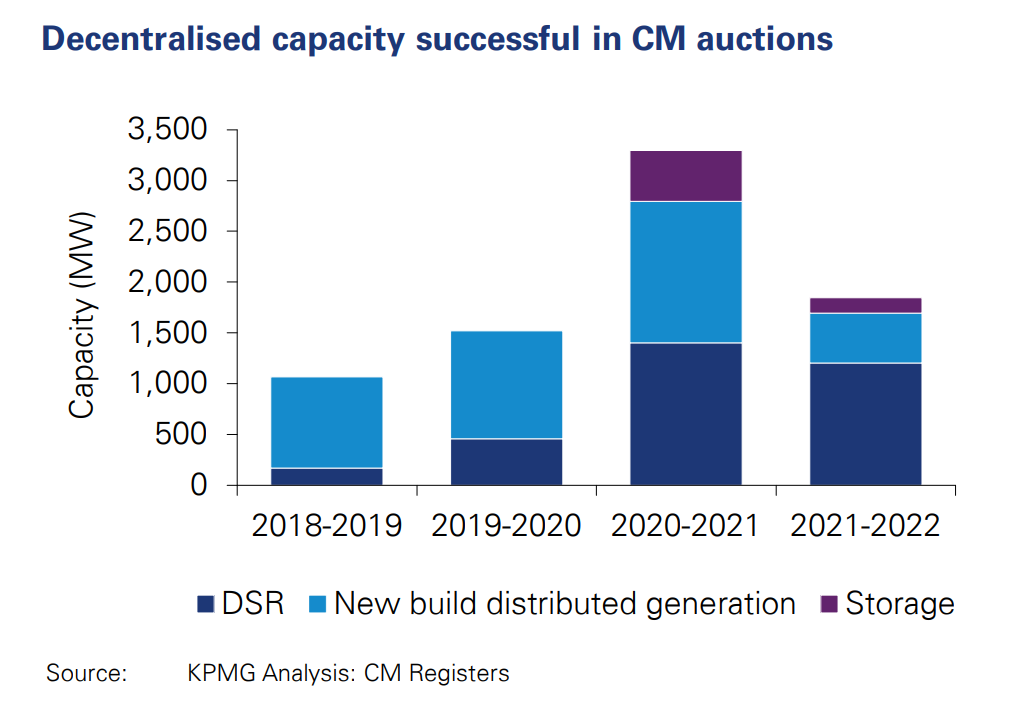

In contrast, successive auctions have contracted increasing numbers of small, decentralised providers, such as DSR, new peakers and storage, as the chart below shows. (Interconnectors linking the UK to the rest of Europe joined the 2021/22 auction, reducing the space for others.)

Decentralised capacity winning capacity market agreements in each of the main auction rounds held so far, megawatts (MW). Source: KPMG.

What does the ruling say?

The EU court ruling has the effect of making the UK’s capacity market illegal. This is because it annulled the 2014 European Commission decision to approve the measure.

The General Court ruling concludes that the 2014 approval process – which was based on a one-month preliminary “phase 1” investigation – was too short. The approval had: “incomplete and insufficient content…owing to the lack of appropriate investigation.”

The ruling says the commission should have had “doubts” about whether or not the scheme was compatible with state-aid rules. Consequently, it should have launched a “phase 2” formal investigation into the scheme. Finally, the ruling annuls the 2014 approval.

For the UK government, this ruling is a “procedural” matter for the commission, which failed to follow due process and must, therefore, go back and do its homework again. It says:

“The design of the capacity market has not been called into question, and our focus is therefore on ensuring it can be reinstated as soon as possible.”

A document sent to capacity market participants by the GB electricity system operator similarly says the judgement merely “suspends” the scheme and that it will be on hold until “[it] can be approved again”. This language hints at an expectation that the scheme can be re-approved as-is.

The commission itself also appears to be viewing the ruling as a largely procedural matter. In a statement emailed to Carbon Brief it says:

“The commission takes note of [the] judgment of the general court and will analyse it carefully. In particular, the court has identified certain procedural issues with the commission’s decision. We will assess these points carefully and take the necessary measures prescribed by the court in the judgment.”

Tempus Energy and some others disagree with this sanguine assessment of the ruling’s impact. As Sara Bell, Tempus founder and CEO, explains in a response to the UK government line:

“The case that Tempus Energy brought was a procedural challenge, because we were challenging the European Commission’s decision not to launch a thorough investigation into the substance of the capacity market.

“However, the reason the court upheld the challenge was precisely because of the serious concerns raised by the design of the scheme. Therefore, the nature of the capacity market was very much at the heart of the decision.”

The court ruling did not adjudicate on the substance of the concerns raised by Tempus Energy’s case. It merely says that their existence should have given rise to “doubts” – a legally defined term in this context – and that this alone should have triggered further investigation.

Nevertheless, the ruling will effectively force the commission to consider the concerns of Tempus and others during the formal investigation that it now seems committed to launch. During this process, it will have to gather evidence from interested parties – a step it failed to take in 2014.

The ruling says the commission cannot avoid a formal investigation simply because it would be quicker or more economically and politically convenient to do so. The document sent to market participants also concedes that “the commission will now need to undertake a formal investigation”.

KPMG’s Virley tells Carbon Brief:

“This is much more significant than just a ‘procedural matter’ as Greg Clark insisted last week. Generators will be without their expected capacity payments this winter. This ruling also means considerable uncertainty about how the capacity market will operate going forwards. As a result, some will be considering early closure, or putting planned projects on hold.”

The legal NGO ClientEarth has a more detailed legal summary of the ruling, covering the legal status of the term “doubts” and the various stages of state-aid approval. The possible impacts of the ruling, mentioned in Virley’s quote, are covered in more detail in the sections below.

Will the capacity market have to change?

After the ruling, the UK government quickly announced that the market would enter a period of “standstill”, during which no payments would be made and no further auctions would be held. This move was required under the UK’s capacity market legislation. The government says it is:

“Considering the judgement in detail alongside the European Commission, and [is] working to support the commission as they consider the legal options available to them.”

One option is for the commission to appeal the ruling within two months – the UK government cannot do so – but an appeal could take many months and would have an uncertain outcome.

Instead, the commission will probably have to go through its formal investigation process in order to re-approve the scheme. The GB system operator says it “can’t speculate” on how long this will take. However, a number of pointers are available.

Tom Edwards, senior modeller at energy market consultants Cornwall Insights tells Carbon Brief:

“The French capacity market was relatively simple and took nine months to be approved. The Polish market took 20 months…I will hedge my bets and say it will take 12-18 months for the UK’s to be re-approved, but it could be as long as 20 [months].”

It also appears likely that the UK scheme will require amendments before it can be re-approved. This is because it was the first capacity market considered by the European Commission and, hence, was something of a test case.

Since 2014, the commission’s view has evolved and it now has a greater understanding of matters such as DSR, says Sophie Yule-Bennett, a freelance lawyer who has worked for Tempus Energy on its case. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Our understanding is that the commission won’t simply apply a snapshot of 2014 rules [when it reconsiders the UK’s scheme], it has to take into account subsequent developments including…its own sector inquiry into capacity markets.”

This is a key legal point that remains unclear. The UK capacity market will be judged according to the rules applicable at the time it was “notified”. The original scheme was notified in 2013, whereas an amended or reformed scheme may or may not need to be subject to a new notification.

Since 2014, the commission has also published guidelines that cover the appropriate design of such markets. Based on this guidance, it required both the French and Polish schemes to make significant amendments before they were approved.

These changes included allowing power plants in other member states to enter the market, giving preference to low-carbon generators and giving greater access to DSR participants. According to ClientEarth, the Polish market does meet these requirements – “in contrast to the British scheme”.

The UK scheme only allows the cables that supply power from neighbouring countries to participate, not the foreign power plants themselves. It also restricts DSR providers to one-year contracts – not the 15-year deals available to new power stations – whereas the Polish market offers DSR contracts of up to five years.

Dr Tim Rotheray, director of the Association for Decentralised Energy (ADE), tells Carbon Brief:

“From our perspective the government does indeed need to give more focus to enable DSR to be in the capacity market on a level playing field and we hope that this ruling will ensure that government focuses on ensuring fair access for DSR as this could contribute to keeping a lid on costs of power for all.”

In a blog, Tempus Energy’s Bell says:

“The need for demand flexibility in the energy system, to balance intermittent renewables and deliver security of supply at the lowest cost to customers, is more urgent than ever before. This is a critical opportunity to finally get our energy policy right, so that demand-side response, storage and renewables can work together to provide cleaner, cheaper capacity.”

Bell tells Carbon Brief:

“I intend to enforce the hell out of this judgement. There is no time to waste in solving climate change. The faster the money flows in the right direction, the faster we solve climate change.”

Another complication is the capacity payments already made so far. The lion’s share of these – some £378m – were made under a one-off supplementary auction for last winter, which has separate state-aid approval. This means they are not immediately rendered illegal by the EU ruling, which only annulled the main 2014 approval. Yet they could still fall foul of this process later on.

The lower amounts paid so far under the main capacity market scheme, meanwhile, are technically illegal and could be subject to claw-back. The government says it “is taking no steps to recover payments at this stage, and hopes that this can be avoided”.

The UK’s decision to leave the EU makes for yet another complication in this process. It is due to leave at the end of March 2019, by when the capacity market case is unlikely to have been resolved.

However, under the draft UK-EU withdrawal agreement, EU state-aid rules would continue to apply during a transition phase until 2021 or 2022. The draft political statement on the future UK-EU relationship, meanwhile, also says the UK would maintain a “level playing field” on state-aid.

Outline of the political declaration setting out the framework for the future relationship between the European Union and the

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Source: European Commission

If the UK leaves the EU without a deal, it would technically no longer be subject to EU state-aid rules or EU rulings. Yet the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority, which would be in charge of any future capacity market in this scenario, would probably have to consider EU case law in its decisions, Yule-Bennett says.

What about other reforms?

There are two strands of reform that could force change on the UK capacity market, regardless of the EU ruling and any re-approval for the existing scheme.

The first is the UK’s own five-year review of its EMR policies, including the capacity market. The government has already issued a call for evidence on this and had been thought to be considering changes including allowing subsidy-free windfarms to compete for capacity contracts.

The second is an EU electricity market reform package that is due to be finalised in December. This could impose a ban on capacity payments to new plants emitting more than 550gCO2 per kilowatt hour from 2025, with payments to existing plants decreasing from 2025 and ending by 2030. If agreed, this would effectively rule out contracts for coal in the longer term.

Will power plants close?

The UK government says it remains committed to the capacity market and will seek its reapproval as soon as possible.

Pending this reapproval, it will seek one-off permission to run a capacity market for next winter. The auction would need to take place next year and would need to at least be in the pipeline before any power stations decided to close. As explained in more detail, below, closures are most likely to be announced before April 2019. This means the timelines are extremely tight.

Meanwhile, the government is telling generators that they should continue to abide by their capacity market contracts, even though the contracts currently hold no legal force, according to a source in the room at a meeting held by energy regulator Ofgem last week.

Cornwall Energy’s Edwards tells Carbon Brief:

“If the scheme is re-approved, the risk is power plants that decided to close would have to pay termination fees [under their capacity market contracts]. But at the moment, the scheme is illegal.”

Even if they had to pay these fees, however, it might still make sense for some plants to close down. Any decision to close depends on a range of factors for two broad categories of plant.

First, large old coal or gas plants could close earlier than expected. Second, a raft of new peaking plants and battery storage sites might put their construction on hold or might even be cancelled.

The ruling is not expected to have an impact on capacity this winter, however. This is because power plants earn much of their revenue in the winter months, when electricity prices are high.

Large power plants have also already paid for annual access to the grid. If they were going to close, it is likely they would do so after winter, but before the next yearly fee falls due in April 2019.

Meanwhile, smaller plants stand to earn lucrative “triad payments” under a scheme designed to minimise demand from large electricity users during the three periods of highest stress on the system, known as triads. (These payments are set to partially dry up and will disappear for many generators by April 2021, Edwards says.)

Once the winter is over, operators will be scouring their balance sheets to decide whether it makes sense to pay for another year of grid access and hold out for the capacity market to return, or whether to close.

A number of large sites had only remained open or returned from being “mothballed” because of extra income from the capacity market, Edwards says, pointing to gas plants at Peterhead in Scotland, Keadby in Linconshire and Medway in Kent.

Older gas and especially coal plants have the largest fixed costs, just to keep their plants open, and hence potentially also the largest incentive to cut their losses and close, Edwards says.

Indeed, some coal plants had already been expected to be at risk of closure next spring, since they had failed to secure capacity contracts beyond this year. This is shown in the first bar chart, above.

Large coal or gas plants therefore pose the highest-profile risk to security of supply, since even one closure could make a significant difference to the balance between electricity supply and demand.

Operators are well aware of this and may seek to use it as leverage for another form of support, even if the capacity market is not reinstated next year, Edwards suggests. For example, they could push to reopen the “supplementary balancing reserve”, which operated before the capacity market.

On the other hand, early coal closures might be welcomed by government as taking the UK closer to its 2025 phaseout.

Smaller operators face a slightly different calculus. They may have been counting on capacity payments to repay creditors and hence be faced with cashflow problems. Alternatively, they might risk staying open on the assumption that a large coal closure or two would push up market power prices and hence their earning potential. Edwards explains the questions they will ask:

“Do I sell? Do I dismantle and move [the plant to another country]? Do I calculate wholesale prices will be higher if someone else closes? If this is a plant under construction, do I halt and wait? That, too, could affect market prices.”

The ADE’s Rotheray tells Carbon Brief:

“There may be some operators only dependent on the capacity market, but for many it will be more about the stack of values [including the capacity market, wholesale power prices and contracts for providing grid services, such as reserve power or frequency control].”

The uncertainty created by the EU ruling also extends to larger gas plants that were due to be built. The “Keadby 2” gas plant in Lincolnshire has already broken ground and may still go ahead, whereas a planned plant at the site of the former Eggborough coal plant in Yorkshire had yet to secure a capacity contract and may be put on hold.

For French nuclear operator EDF, the longer-term future of the UK capacity market will weigh on its decision to invest in extending the life of its current reactor fleet, Edwards adds.

What about other countries?

The UK’s capacity market – which covers Great Britain only – was the first of several to have been subsequently approved in the EU. These include markets in Poland, Italy and France, as well as one covering the island of Ireland.

At this stage, it remains unclear whether the UK ruling will affect markets elsewhere. In a statement, Joanna Flisowska, coal policy coordinator at Climate Action Network (CAN) Europe, says:

“[The court ruling] confirms that, in practice, capacity mechanisms are used to hand out money to fossil fuels rather than for security of supply. This casts doubt on other capacity markets, especially the Polish one.”

The initial indications are that there will be no direct spillover, however. Forum Energii, a Polish thinktank, says in a blog: “We believe that suspension of the capacity market in the UK does not directly affect Poland.”

One reason for this is that the Polish scheme was subject to detailed scrutiny in a full formal investigation by the European Commission, unlike the UK market. It was this failure of process that, ultimately, led to the UK’s approval being annulled.

The Polish scheme has just run its first auction, awarding contracts worth around PLN5bn (£1bn) for 23GW of capacity in 2021. Most of this will go to coal, including 3.5GW of new plants that will receive 15-year contracts out to 2035. This is well beyond the point when the EU should have phased out coal, according to model pathways able to meet the 1.5C goal.

Poland will also run auctions for 2022 and 2023 in December this year. The cost of the Polish scheme is relatively high per kilowatt (kW) at up to PLN240/kW (£50/kW), compared to prices of £6-22/kW for the various auctions rounds under the GB market.

-

Q&A: What next for UK capacity market after surprise EU ruling?

-

Q&A: How might the EU’s surprise ruling affect the UK capacity market?