Q&A: What does the new German coalition government mean for climate change?

Josh Gabbatiss

12.02.21Josh Gabbatiss

02.12.2021 | 4:22pmFollowing two months of negotiations, three political parties have agreed to form a new government in Germany, after hammering out a deal that includes plans to rapidly scale up renewables and “ideally” phase out coal power by 2030.

Climate change was seen as an important issue in a federal election that coincided with deadly flooding in western parts of the country, linked to rising global temperatures.

The centre-left Social Democrats (SPD) emerged victorious in September and have since agreed a coalition treaty with the Green party and the pro-business Free Democrats (FDP). They will form the first “traffic light” coalition government at federal level.

This marks the end of a 16-year period in which Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) ruled in coalition and oversaw significant expansion of the nation’s renewable power, but also faced criticism for phasing out nuclear and continuing to rely on coal.

With the SPD’s Olaf Scholz set to take over as chancellor of Europe’s largest economy – and biggest emitter – his government’s decisions on energy and transport will have major implications. The nation is currently not on track to meet its recently revised climate targets.

In this piece, Carbon Brief explores the current state of climate action in Germany and the path ahead for its new government, including the details laid out in a new treaty that will form the basis of the coalition’s policies.

- What is the state of climate politics in Germany?

- What are the coalition parties’ positions on climate change?

- How is Germany progressing on its climate targets?

- What has the coalition pledged so far on climate and energy?

What is the state of climate politics in Germany?

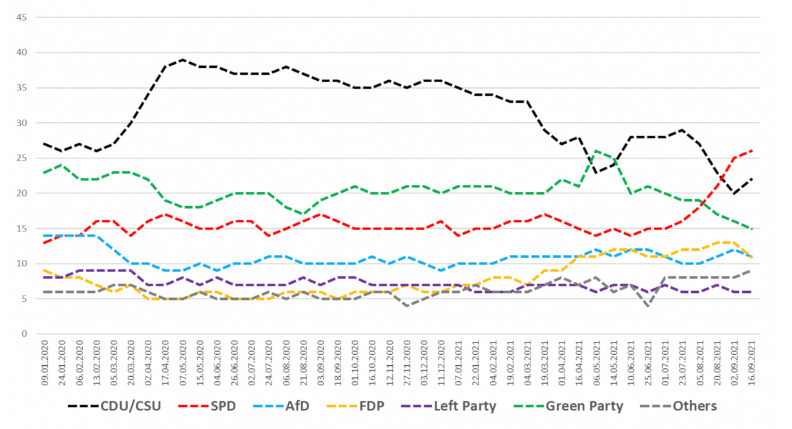

This year’s federal election was marked out as different when polls briefly showed the Green Party overtaking the ruling centre-right CDU and sister party the Bavarian Christian Social Union (CSU) in public favour for the first time in years.

This can be seen in the chart below, with previous CDU coalition partners the SPD ultimately overtaking the Greens as the year wore on.

This progress for the Greens was attributed in part to the importance of climate change among the German electorate. Ultimately, the party took the third-largest share of votes after the dominant SPD and CDU, earning a key position in the new coalition.

Many pundits and analysts dubbed it the “climate election”, although others argued that climate concerns ultimately failed to sway as many voters as initially predicted.

Various polls in the run up to election day indicated that climate change was a cause for concern among Germans, and a survey of 28 countries carried out by Ipsos and released at the start of September found that they were the most worried of all those asked.

In recent years Germany has been repeatedly struck by extreme weather, including droughts and floods, and a significant youth climate protest movement has emerged.

At the height of the election campaign, devastating floods struck areas of the country, killing around 200 people. A subsequent attribution study revealed the event was made up to nine times more likely by rising global temperatures.

The election also took place at a time of intense scrutiny for German climate policy. Despite years of growth in renewable power as the nation undertook its Energiewende – energy transition – to shift away from both coal and nuclear power, the country has nevertheless made mixed progress on reducing its emissions.

After admitting it would fall short of the country’s climate goal for 2020, the coalition CDU/CSU and SPD government introduced Germany’s first ever climate action law in 2019, legally defining its emissions targets for the first time.

However, the package was dismissed by NGOs and thinktanks as “shockingly feeble” and “far too cautious”, in part due to its low carbon price.

Shortly before the election, a landmark court decision ruled that Germany’s climate law was insufficient on the grounds of intergenerational justice, requiring the government to provide details of its emissions reduction targets beyond 2030.

Responding to the ruling, the German parliament amended the law to bring forward its net-zero target by five years to 2045 and tighten its 2030 target from a 55% cut compared to 1990, to a 65% cut over the same timeframe. It also set a new target of an 88% cut by 2040.

However, the bill was opposed by some parties including the Greens and the FDP, which have since joined the SPD in a coalition. The Greens called for more ambition while the FDP described it as inefficient.

Meanwhile, July saw the European Commission release its proposals for how the European Union (EU) should ramp up its climate action in order to meet its legally binding target to cut emissions to 55% below 1990 levels by 2030, known as the “Fit for 55” package.

The proposed changes, which will now undergo lengthy negotiations among member states, were welcomed by then-state environment secretary and SPD politician Jochen Flasbarth as “nothing less than a new industrial revolution in the EU”.

What are the coalition parties’ positions on climate change?

There is a general consensus across German politics on climate change, with every major party backing a net-zero target of between 2040 and 2050 going into the election. Only the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) explicitly opposes climate action.

However, the parties have different approaches to climate change that are likely to shape Germany’s progress in the coming years under its new “traffic light” coalition government of the SPD (red), FDP (yellow) and Greens.

Broadly speaking, the Green party has the most ambitious climate policies, campaigning for a petrol and diesel car phaseout by 2030, 100% renewable electricity by 2035 and, if that is achieved, the party says net-zero emissions would be possible “within 20 years”.

The FDP, on the other hand, did not campaign on targets for reaching 100% renewables or phasing out fossil-fuelled cars, calling for a net-zero target of 2050.

Finally the SPD, which took nearly as many votes as the other two parties put together, has a more middle-of-the-road approach to climate action. Its net-zero manifesto target was 2045, matching the one recently set into German law, and it also had a target of 100% renewable electricity by 2040.

These policies can all be seen in a grid of manifesto pledges assembled by Clean Energy Wire.

The SPD’s Scholz, who is expected to take over as chancellor in early December, is a relatively unknown quantity when it comes to climate issues.

While he pledged to “halt man-made climate change” following the election result, his voting record shows he has focused more on regional issues in state parliament than climate policy, according to analysis by Deutsche Welle.

Analysis conducted ahead of the election by the consultancy DIW ECON, commissioned by the Climate Neutrality Foundation, concluded that none of the parties likely to end up in government had manifestos that matched up to the ambition of Germany’s climate goals.

(This is perhaps unsurprising given that these plans were largely finalised by the time the climate law was revised in June.)

Notably, the report concluded that the FDP’s strategy was the least ambitious on climate, and the Greens’ was the most ambitious, with the SPD in the middle.

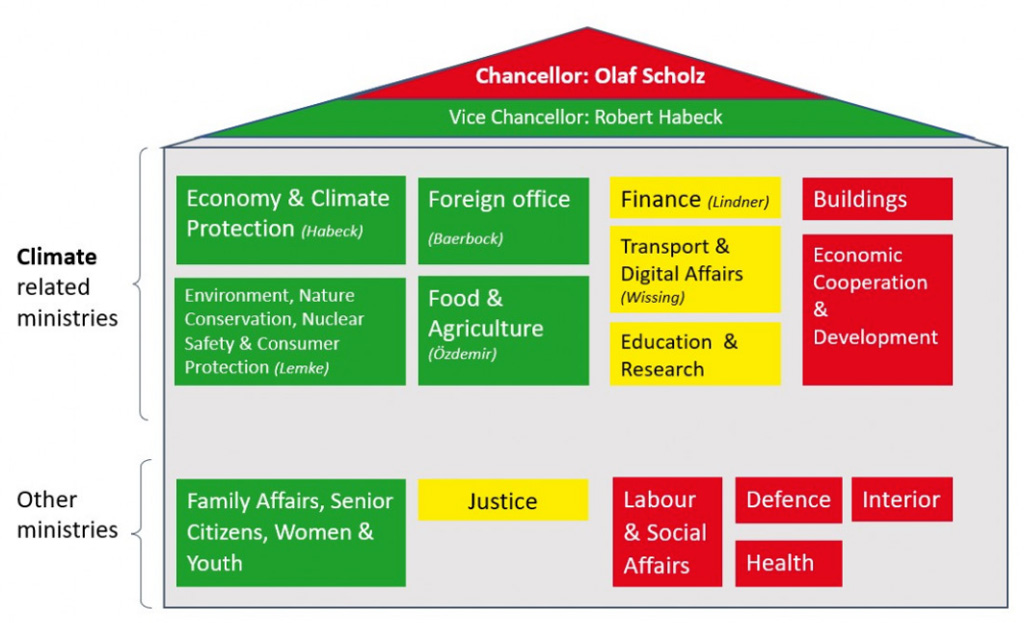

The different stances could be significant now these parties have joined together in coalition, dividing up ministries between them.

As the chart below shows, the SPD, as the party with the most votes, has the largest remit but is only set to run two ministries viewed as important for climate goals – overseeing buildings and “economic cooperation and development”.

Meanwhile the Green party will be responsible for five ministries, including the environment and agriculture as well as a newly formed “super ministry” for climate, energy and the economy, led by the party’s co-leader Robert Habeck, who will also be vice-chancellor.

However, during negotiations the Greens had also pushed to take on both the finance and transport ministries – both of which have significant climate responsibilities – but ultimately they lost out to the FDP.

While the party’s fiscally conservative outlook could be viewed as a barrier to climate spending, Frank Steffe, a policy expert at thinktank Agora Energiewende, tells Carbon Brief:

“We have the climate goals, we have the climate law, the European green goal and we have the Paris Agreement…. The FDP can read all these laws.”

He noted that while the initial coalition treaty did not contain new spending figures, it does include references to financial measures and strong language around reaching 1.5C.

The FDP, which campaigned on a rejection of both speed limits and bans for petrol and diesel cars, will now also be charged with overseeing the decarbonisation of German vehicles.

Dr Giulio Mattioli, a transport policy researcher at Technical University Dortmund, tells Carbon Brief that broadly the FDP supports market-based solutions and technology at the expense of demand-side measures. It also emphasises the “strong emotional attachment of voters to cars”, he adds.

Nevertheless, Dr Brigitte Knopf, secretary general of the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC) tells Carbon Brief.

“When presenting the coalition agreement, the new partners tried to give the impression that something new can be formed out of the old antagonisms and that Germany can really move forward…Even the FDP agrees to a ‘transformation of the automotive industry’ – acknowledging that the age of the combustion engine has come to an end.”

How is Germany progressing on its climate targets?

Germany has consistently been off track against its climate targets. For years, there were warnings that the nation would likely fall short of its 2020 goal to cut emissions by 40% from 1990 levels.

A government report in 2018 suggested cuts would be closer to 32%. A government report blamed unexpectedly high economic and population growth, although some observers have argued that the biggest threat to the government’s target remains its reliance on coal power.

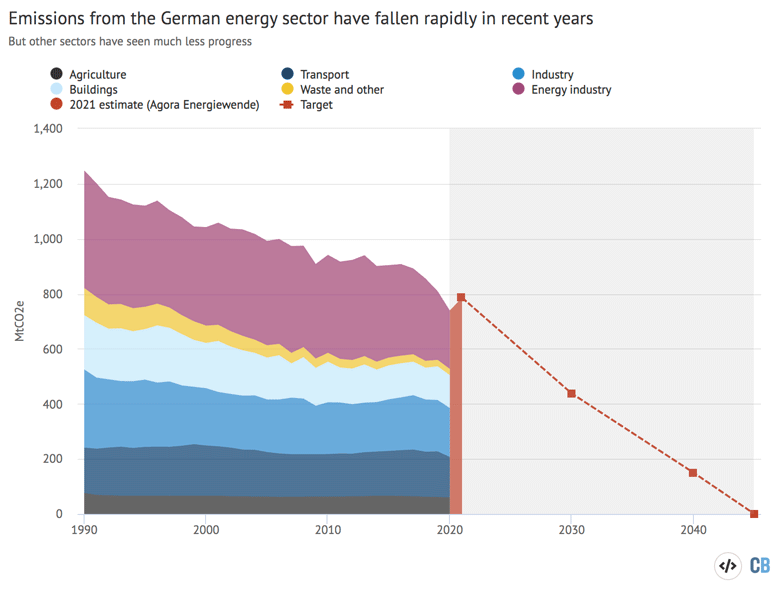

As the chart below shows, while there has been progress in cutting emissions from energy industries – including the power sector and other operations such as oil refineries – key sectors such as transport have seen little change.

As it turned out, according to thinktank Agora Energiewende, Germany managed to overachieve on its 2020 target, cutting emissions by 42.3% from 1990 levels, compared to the 40% goal.

However, this would likely not have been the case were it not for the economic shock of the Covid-19 pandemic causing a last-minute dip in emissions, with the environment ministry itself admitting its policies would only have delivered a 37.5% cut.

Indeed, recent analysis by Agora Energiewende suggests that following the Covid-19 dip, 2021 is now seeing the fastest increase in emissions for at least three decades.

With 2030 on the horizon, Germany once again looks set to miss its next set of targets, unless it implements stronger policies to close the gap.

Official analysis from 2019 based on the original goal – a 55% cut by 2030 – suggested the government was far off track,. The latest government analysis suggests the country will not meet its new, more ambitious target either.

Rather than cutting emissions by 65% by 2030, a leaked version of the document, reported by German press in August, indicated that only a 49% cut was expected in this timeframe. By 2040, emissions were only expected to fall 67%, rather than 88%.

The environment ministry argued that the report was already outdated as its cut-off point in August 2020 meant it did not include the rapid developments in climate policy that had taken place in the intervening year.

Nevertheless, experts say that far more will be needed to meet the new targets. Cora Herwartz, a policy adviser based in Berlin with thinktank E3G tells Carbon Brief:

“The new climate law put the incoming government under pressure to quickly come up with an implementation strategy fit to deliver the necessary emission cuts. Otherwise, Germany will not be able to reclaim its climate frontrunner role in a credible way.”

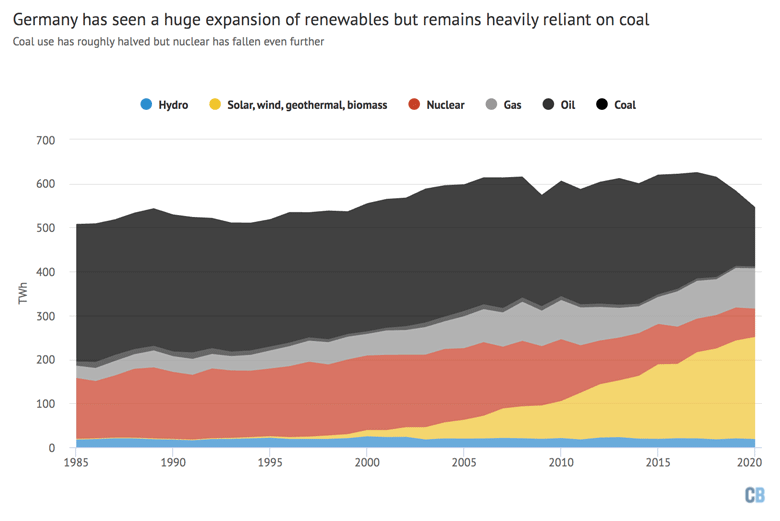

Germany now generates nearly half of its electricity from renewables, which overtook fossil sources for the first time in 2020, after years of investment. However, despite roughly halving coal use since 2015, its grid remains heavily reliant on the fuel, making the sector one of the key barriers to further decarbonisation.

While wind and solar have experienced enormous growth under Germany’s Energiewende, the accompanying shutdown of nuclear power plants means part of the expansion has simply replaced one form of clean power with another, as the chart below shows.

In order to avoid a “green electricity gap”, Prof Claudia Kemfert, who leads on energy, transport and the environment at the German Institute of Economic Research (DIW Berlin), told Carbon Brief ahead of the election that annual expansion rates for renewable technologies need to be tripled.

“Not only because Europe has tightened its climate targets once again and Germany must quickly follow suit. But above all because the German government is clearly underestimating future electricity demand,” she added. (The most recent government estimate was for 2030 electricity demand to reach 658 terawatt-hours, TWh, but the new coalition deal accounts for demand increasing to 680-750TWh.)

Dr Ralph Harthan, a senior researcher at the Öko-Institut, which helps to produce the reports assessing Germany’s climate progress, tells Carbon Brief that other areas also present significant challenges:

“Due to the inertia of the capital stock, the buildings and the transport sectors constitute the most significant challenges for achieving the 2030 emission targets”

A proposal released in August by a group of German thinktanks called for whichever government took power to “implement a comprehensive climate action emergency programme in its first 100 days”. Their 50 recommendations included the following targets by 2030, several of which have been adopted by the incoming coalition (see below)

- A coal power phaseout by 2030, rather than 2038.

- Expansion of renewables to cover 70% of power generation.

- 14m electric cars on the road.

- One-third of the distance covered by lorries to be “CO2 free”.

- €12bn per year to fund zero-carbon new buildings and green renovations.

- Introduce carbon contracts for difference (CCfD) to help decarbonise heavy industry.

The required action would constitute the “biggest climate action programme in the history of the federal republic”, according to Agora Energiewende executive director Dr Patrick Graichen, who has since taken on a role within the new climate ministry.

It is worth noting that according to Climate Action Tracker, to be in line with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C ambition, Germany’s 2030 target should aim for emission reductions of “at least 69% below 1990 levels” – 4 percentage points more than the current goal.

What has the coalition pledged so far on climate and energy?

The new coalition has released a treaty outlining its policies over the next four years, titled “Daring more progress – alliance for freedom, justice and sustainability”.

Climate and energy are both prominent topics in the document, and many of the commitments match up with the proposals laid out by climate experts in the run-up to election day.

However, experts tell Carbon Brief there is also evidence in the text of the struggles of three different parties searching for compromise on hotly contested issues.

The text emphasises the importance of making Germany’s emissions compatible with a pathway to the 1.5C global warming target. However, experts predicted that the policies laid out in the treaty alone would not be enough to get there.

Climate targets

Even though Germany’s climate targets were already being strengthened as parties campaigned, the ambition of these targets remained a source of dispute during coalition discussions.

The Greens wanted to see Germany’s 2030 goal increased from a 55% emissions reduction to 70%. The SPD had also campaigned for the short-term goal to be strengthened, although only to the 65% cut that has already been legislated.

Meanwhile, the FDP wanted to get rid of sectoral emissions targets, which were only recently introduced in Germany’s climate law for the years 2020-2030.

Sabine Gores, a senior researcher at the Öko-Institut, tells Carbon Brief she sees “a high advantage” in keeping these in place. “Sectoral targets ensure that emission reductions take place in all sectors, providing a fair share to overall ambition,” she says.

In the end, the parties decided on a compromise that neither strengthened overall targets nor scrapped sectoral targets. However, they did agree to a “climate check” mechanism for ministries to ensure all new policies are compatible with national climate targets.

There is also language around “reforming” the federal climate action law and monitoring compliance with targets on the basis of a “cross-sectoral and multi-year overall assessment analogous to the Paris Climate Agreement”.

Experts tell Carbon Brief it remains open to interpretation exactly what these lines could mean.

However, Frank Steffe of Agora Energiewende says that following COP26, where countries were “requested” to come forward with new climate pledges in 2022, there may be more pressure on Germany to come forward with a stronger target. (Although the EU has indicated it does not intend to do so next year.)

In the negotiations for the EU’s “Fit for 55” programme, the coalition treaty states its support for “the proposals of the European Commission”, while adding that it wants “instruments in the individual sectors to be as technology-neutral as possible”.

Such “technological neutrality” language is popular among German industry groups and the FDP, but in areas like the automotive sector is sometimes viewed as an excuse for inaction.

Nevertheless, Dr Brigitte Knopf of MCC tells Carbon Brief that the new government’s show of support for Fit for 55 is “positive and very important”.

More broadly, while some sectors were still lagging in the treaty, Knopf says that in her view “this coalition brings the country back on track to meet the climate targets”.

Electricity

Germany’s power supply is a key focus of the document and predictably its pledge to phase out coal power “ideally” by 2030 – eight years early than previously planned – received a lot of attention.

In 2020 the nation’s energy industry, primarily its electricity generation, emitted 212.4m tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e), which is 29% of the total. Its emissions have already been cut by 53% since 1990 and under the climate law this figure needs to hit 77% by 2030.

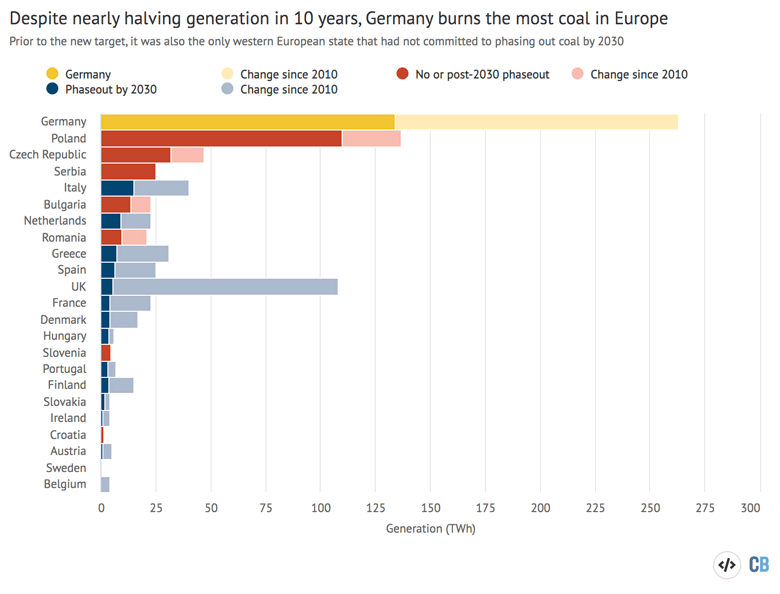

As the chart below shows, Germany – by far the largest coal user in the region – has become isolated in recent years as the only western European nation without a pledge to phase out the fossil fuel over the next decade.

While the use of the word “ideally” reads like something of a compromise to placate German regions that are dependent on coal, Steffe says that in his view it is “pretty clear” that 2030 is the target date. More details are likely to come in 2022 when an evaluation of the coal phaseout law is due.

A key component in enabling the coal phaseout and 2045 net-zero target is perhaps the coalition’s most significant climate pledge – namely to increase Germany’s renewable electricity target for 2030 from 65% to 80% of the country’s supplies.

This includes increasing Germany’s offshore wind capacity from 7.8 gigawatts (GW) to 30GW, and solar capacity from 54GW to 200GW, in just a decade. It is a more ambitious pledge than similar targets pushed by NGOs and thinktanks in the run up to the election.

There is also a commitment to dedicating 2% of German land to onshore wind, up from 0.9% today. Analysis by the Climate Neutrality Foundation suggests this would be enough to boost onshore wind capacity from 55GW to 80GW by 2030, and 130GW by 2050.

However, despite early reports that the deal would include a gas power phaseout date of 2040, this did not appear in the published document, to the disappointment of some climate campaigners.

In fact, it notes that “natural gas will be indispensable for a transitional period” and says that new gas infrastructure should be hydrogen-ready. This implies that Germany plans to base its future electricity mix around wind and solar, with hydrogen as back-up.

Another component of the strategy intended to promote the shift away from coal and fossil fuels generally is a proposal for a “national floor price” that would mean German carbon prices would be prevented from falling below €60 per tonne, even if the EU cannot settle on a minimum price in its emissions trading system, the EUETS.

Transport

The coalition document contains a few major commitments towards decarbonising transport, which emitted 146.7MtCO2e in 2020, or 20% of the total. So far transport emissions have only been cut by 11% since 1990 and the target for 2030 is 48%.

Chief among the pledges is a target of 15m purely electric cars in Germany by 2030, up from around 300,000 today, and aligning with the European Commission’s proposal to phase out petrol and diesel car sales by 2035.

In fact, the treaty states that the EU-wide 2035 target will have an “earlier effect” in Germany. This suggests that it could be pushed closer to the Greens’ favoured phaseout date of 2030.

However, in a nation with a major automotive industry, Jürgen Resch, head of Environmental Action Germany (DUH), said in a statement that “car companies’ handwriting cannot be overlooked” in the document.

For example, the text includes a loophole that allows vehicles that run on synthetic “e-fuels”, which have yet to be scaled up but are supported by industry and the FDP, to continue being registered “outside the existing system of fleet limits”.

Dr Giulio Mattioli from Technical University Dortmund, says that another issue is how the ambitious electric vehicle targets are going to be reached:

“Some people are saying that this goal of 15m would imply that by the end of the decade nearly 100% of vehicle sales would be battery electric… if you look at countries that follow that exponential curve, like Norway, they have achieved that by creating a huge differential in price whereby they have taxed petrol and diesel vehicles a lot.”

While Germany does have subsidies in place for electric vehicles, Mattioli points out that at the same time, the incoming FDP transport minister Volker Wissing intends to cut taxes on diesel vehicles, rather than raising them.

The coalition document also includes a commitment to scaling up charging infrastructure, something that is seen as holding back electric vehicle expansion but has seen only gradual progress so far from the German government. “I’m not entirely convinced that will happen either,” says Mattioli.

The coalition has omitted speed limits on motorways, which were supported by the Greens and SPD, but are opposed by the FDP that now runs the transport ministry.

According to the German Environment Agency, a speed limit of 130km/h, as proposed by the parties, would cut German emissions by 1.9MtCO2.

However, there were some other significant elements for environmentalists, including plans to prioritise rail spending over road spending.

Buildings

The SPD, which will be in charge of the ministry overseeing buildings, made constructing 400,000 new housing units every year a cornerstone of its election campaign. The coalition deal also includes details about how emissions in homes could be reduced.

Commercial and residential buildings accounted for 119.2MtCO2e of emissions in 2020, 16% of Germany’s total. These emissions have fallen 43% since 1990 and under the climate law must continue falling to 68% by 2030.

Press leaks suggested that following negotiations the coalition had agreed to ban new gas boilers from 2035, but this did not make it to the final text.

Instead, the treaty contains a pledge that by 2025, every new heating system must run on 65% renewable energy, a target described by the European Environmental Bureau NGO as “highly disappointing”, as “hybrid solutions should be left only for niche renovation markets such as protected buildings”.

Another new 2025 pledge is for all new buildings to have just 40% of the energy consumption of a so-called reference building, an improvement on the existing 75% target.

With such developments in mind, and considering the difficulty of negotiations, Steffe tells Carbon Brief:

“I think the building chapter is sort of a hidden treasure…it’s much better than we expected.”

Specifically, he says that the 65% target marks “the end of fossil heating” in homes, providing a “very good remit” for heat pumps and other low-carbon technologies.

The coalition did not increase the carbon price for heating fuels, citing social reasons as energy prices are still very high, although it would propose a new pricing system in 2026, with a “climate payment” to compensate some consumers for price increases.

Knopf says this is the “least ambitious element” of the treaty, as it will mean the price will only be at €55 in 2025, below the EUETS price now.

Other areas

Some of the remaining policy areas are less well-developed, with fewer specific targets, but nevertheless there are various important signals for German climate policy.

In heavy industry, the new document mentions introducing instruments such as carbon contracts for difference – a means of supporting progress in hard-to-decarbonise areas such as steel production, that has been championed by thinktanks.

Industry currently accounts for 178.1MtCO2e of annual emissions, or 24% of the total. The sector’s emissions have been cut by 37% since 1990 and must drop by 58% under Germany’s climate law.

The treaty also pledges to double plans for hydrogen electrolyser capacity – that is hydrogen produced using electricity rather than gas – to 10GW by 2030.

The document also clearly prioritises this “green” hydrogen over other varieties, mentioning quotas for green hydrogen in public procurement to boost the industry.

Finally, the treaty includes language around modifying agricultural policy to help cut emissions, including presenting a concept for how direct payments under the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) could be replaced with a system that pays for environmental and climate services.

At 60.4MtCO2e in 2020, agriculture is responsible for 8% of German emissions. These emissions have fallen 24% since 1990 and the climate law requires them to fall by 36% by 2030.

It also references bringing livestock animal numbers in line with broader targets of climate and water protection.

-

Q&A: What does the new German coalition government mean for climate change?