Q&A: What does Biden’s LNG ‘pause’ mean for global emissions?

Multiple Authors

01.30.24Multiple Authors

30.01.2024 | 4:51pmIn a surprise move, US president Joe Biden has announced a “temporary pause” on liquified natural gas (LNG) terminal expansion.

It has been described by some as an “election year decision” to please climate activists and by others as a distraction that might even raise global emissions.

In recent years LNG exports from the US have boomed, causing the country to leapfrog Australia and Qatar to become the world’s largest LNG exporter in 2023.

These exports have helped Europe make up the shortfall left behind by a drop in fossil-fuel supplies from Russia, following its invasion of Ukraine.

However, current and proposed EU climate policies imply a significant drop in demand for fossil fuels, including LNG imports. As such, a group of EU lawmakers have urged Biden not to use Europe as an “excuse” for further expansion.

Citing his reasons for the temporary pause in new terminal expansion, Biden said there is now “an evolving understanding of the market need for LNG, the long-term supply of LNG and the perilous impacts of methane on our planet”.

Indeed, there is already more than enough LNG export capacity to meet global demand for the fuel, if countries meet national and international climate goals.

But the move has drawn criticism from some commentators and fossil-fuel industry representatives, who have argued that it could lead to countries sourcing LNG from other countries with more polluting practices – or even encourage them to use more coal.

Below, Carbon Brief sets out the reasons why Biden has paused approvals of new LNG terminals, how much LNG capacity is currently in the global pipeline and whether the world really needs more US LNG exports.

It also explores how Biden’s move could affect global emissions, noting that criticisms put forward by oil industry representatives contradict evidence showing that all fossil fuels must rapidly be phased out to meet the world’s climate goals.

- Why has the Biden administration ‘paused’ new LNG expansion?

- How much new LNG capacity is currently in the US, and global, pipeline?

- Does the world need US LNG following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine?

- How will the supply of US LNG affect global greenhouse gas emissions?

- How will the move affect US politics in the coming months?

Why has the Biden administration ‘paused’ new LNG expansion?

On 9 January, Politico reported that Biden’s aides were considering conducting a review that “could tap the brakes on the booming US natural gas export industry”.

It said that the review was being led by the Department of Energy and would “examine whether regulators should take climate change into account when deciding whether a proposed gas export project meets the national interest”.

Examining Biden’s possible motivations for such a review, Politico said:

“US gas exports have jumped four-fold during the past decade as production has surged, turning the US into the world’s largest natural gas exporter and helping Europe replace Russian shipments after Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine. But Biden also faces growing pressure from environmental groups to live up to his pledge to transition away from fossil fuels – something the US also promised to do at last month’s climate summit in Dubai.”

(Nearly every country in the world agreed to “transition away from fossil fuels” at the COP28 climate summit in Dubai in 2023 – with the US among countries at the talks having called for even stronger wording on a total phase-out of coal, oil and gas.)

On 25 January, several publications speculated that the Biden administration was set to announce a review of approvals for new LNG export terminals.

The next day, the Biden administration released a statement announcing “a temporary pause on pending decisions on exports of LNG to non-FTA [free trade agreement] countries until the Department of Energy can update the underlying analyses for authorisation”.

The Financial Times reported that the move will “temporarily halt pending applications from 17 projects awaiting approval to proceed”. (If these projects went ahead, they would together export enough gas to produce more emissions than the EU does in a year, according to one analysis.)

The EU is technically a non-FTA country. However, a senior EU figure told the FT that the European Commission was informed about the US announcement in advance and that an exemption would be made for “immediate national security emergencies”. The official added:

“Therefore, this pause will not have any short-to-medium term impacts on the EU’s security of supply.”

Explaining the reason for the pause, the official statement from the US government said that the analysis that currently underpins new approvals for LNG exports is “roughly five years old” and “no longer adequately account[s] for considerations” such as rising fossil fuel costs or “the latest assessment of the impact of greenhouse gas emissions”. It added:

“Today, we have an evolving understanding of the market need for LNG, the long-term supply of LNG and the perilous impacts of methane on our planet.”

(Biden co-launched an international effort against methane, called the global methane pledge, at the COP26 climate summit in 2021 alongside European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen. At COP27, he described action against methane as a key “gamechanger” for tackling climate change.)

In its coverage, the Associated Press described the move as an “election year decision”. It added that Biden might be keen to align himself with environmentally-conscious voters who fear US LNG exports are “locking in potentially catastrophic planet-warming emissions when the Democratic president has pledged to cut climate pollution in half by 2030”.

Speaking to this suggestion, the official statement from the Biden administration appears to try to make an appeal to voters by saying:

“As Republicans in Congress continue to deny the very existence of climate change while attempting to strip their constituents of the economic, environmental and health benefits of the president’s historic climate investments, the Biden-Harris administration will continue to lead the way in ambitious climate action while ensuring the American economy remains the envy of the world.”

The statement also references the impact of LNG exports on domestic gas prices, which have already affected US consumers.

It comes after a report from the US Energy Information Administration released this month noted that increasing US LNG exports could fuel domestic gas price rises.

Additionally, local communities living along parts of the US coastline that have seen LNG export terminal expansion have appealed to Biden to halt such projects.

Back in December, Travis Dardar, a fisherman and member of the Isle de Jean Charles tribal community off the coast of Louisiana, told Al Jazeera that LNG export terminal expansion threatened his community’s health and ability to fish for income.

The Biden administration references the impact of LNG export terminal expansion on local communities in its official statement, saying:

“We must adequately guard against risks to the health of our communities, especially frontline communities in the US who disproportionately shoulder the burden of pollution from new export facilities.”

How much new LNG capacity is currently in the US, and global, pipeline?

Unlike coal and oil, which are relatively easy to transport by ship, gas has historically been traded predominantly via pipelines.

This began to change with the development of the LNG industry, where gas is super-chilled to turn it into a liquid that can be transported globally by ship.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine gave further impetus to the already-rapid expansion of LNG capacity around the world, as importing countries scrambled to secure supplies.

An “unprecedented surge” in LNG projects coming online around the world from 2025 is set to add more than 250bn cubic metres (bcm) of new annual “liquefaction” capacity by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

This is equivalent to increasing existing global LNG export capacity by roughly half, the IEA notes.

The US is the biggest driver of this trend, largely thanks to new projects in Texas and Louisiana that will nearly double its LNG export capacity by 2028, according to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). The nation has capitalised on its “shale boom”, which propelled it to become the world’s largest producer of oil and gas.

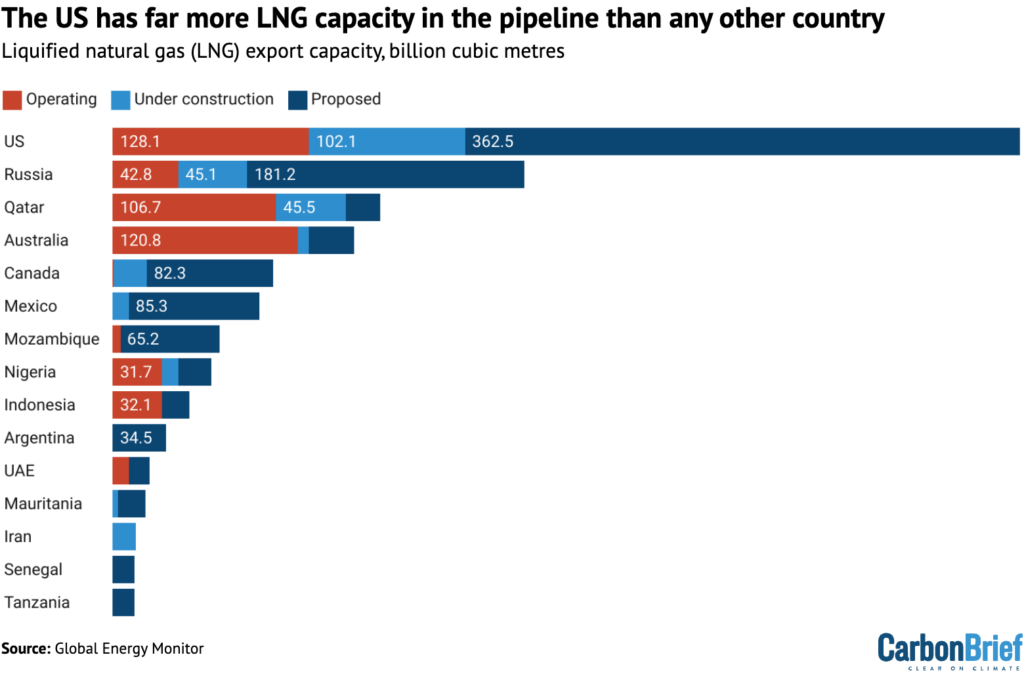

According to figures compiled by Global Energy Monitor (GEM), the US is responsible for 102bcm of the LNG export capacity currently under construction – 38% of the global total.

The US pulled ahead of Australia and Qatar to become the world’s largest exporter of LNG in the first half of 2023, according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). It is expected to remain in this top spot through to 2030. (See this extensive timeline of how the US became the world’s top LNG exporter from Bloomberg reporter Stephen Stapczynski.)

Qatar and Russia are the other major LNG players, both accounting for around 17% of the capacity currently under construction, according to GEM data. Further contributors are set to come from Canada, Mexico, Iran and a handful of African nations.

(There are question marks over Russia’s LNG expansion plans, which have been hit by US sanctions linked to Russia’s ongoing occupation of Ukraine.)

On top of projects that are already underway, an additional 999bcm of LNG export capacity has been “proposed” by companies and governments worldwide, GEM data shows. If this is all given government approval and built, it would double existing capacity.

Again, the US dominates, accounting for 36% of this proposed capacity with 58 projects out of 156, according to GEM data. (The Biden administration’s pause only covers some of these proposed projects and does not cover projects that are already under construction.)

“On average it’s more likely than not that a proposed project won’t get built, but it depends on the country,” Robert Rozansky, an LNG expert at GEM, tells Carbon Brief. He notes that in some nations, such as Qatar, anything that is proposed is likely to be built, while elsewhere they face “slimmer odds”.

Does the world need US LNG following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine?

Russia’s decision to invade Ukraine in early 2022 had far-reaching implications for the global energy system. As of that year, Russia was the world’s second-largest gas producer behind the US and the third-largest oil producer behind the US and Saudi Arabia.

Before the invasion, more than a third of Europe’s gas supplies came from Russia.

But afterwards, the EU brought in new sanctions against Russian fossil fuels, while Moscow restricted supplies, fuelling an energy crisis.

In a report in October, the European Commission said the EU expected imports of Russian gas to drop to 40-45bcm in 2023, compared with 155bcm in 2021, the year before the Ukraine war, according to Reuters.

The drop in supplies from Russia left Europe scrambling for new sources of fossil fuels, with LNG exports from the US helping to make up some of the shortfall.

In December 2023, Europe received 61% of US LNG exports, according to Reuters.

But analysts have noted that Europe’s need for US LNG might be rapidly diminishing.

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a rapid rise of renewables and a drop in energy demand also helped to make up the shortfall left by falling supplies from Russia.

Energy analyst Pavel Molchanov told trade publication S&P Global that “[energy] conservation and increased renewable power may wean Europe off Russian natural gas permanently” in coming years.

Wind and solar supplied more of the EU’s electricity than any other power source for the first time ever in 2022, according to Carbon Brief analysis of figures from the thinktank Ember. Molchanov told S&P Global that he “expected this trend to continue”.

Lars Nitter Havro, a senior analyst for clean technology at energy consultancy Rystad Energy, agreed, saying that the transition to renewable power offered “an unparalleled opportunity for the EU to flip the switch and secure its energy sovereignty”, according to S&P Global.

The European Commission is currently drawing up a proposal to reduce EU emissions by an expected 90% by 2040, on the way to net-zero by 2050. Under the proposals, EU fossil-fuel use could drop 80% on 1990 levels by 2040, according to Reuters.

On Twitter, Dan Byers, vice president of climate and technology at the US Chamber of Commerce’s Global Energy Institute, acknowledged that there would be no EU demand for further LNG expansion, if the bloc meets its 1.5C-aligned climate plans, according to scenarios compiled by Rystad.

Elsewhere on Twitter, Prof Jesse Jenkins, an energy researcher at Princeton University, noted that the scale of US LNG exports is on track to be large enough to “replace peak Russian gas exports to Europe 2.5-times over”.

On 25 January, a group of 60 members of the European parliament wrote to Biden arguing that “big oil” is trying to make Europe “the excuse” for surging LNG exports, the Hill reported. According to the publication, the letter said:

“Europe should not be used as an excuse to expand LNG exports that threaten our shared climate and have dire impacts on US communities.”

According to Reuters, Asia was the second-largest receiver of US LNG in December 2023, with the region taking 27% of exports.

On Twitter, Bloomberg reporter Stephen Stapczynski argued that much of future US LNG exports could go to Asia over Europe – with Asia’s shift away from coal and rapid economic growth potentially boosting the region’s demand for gas.

However, exports to Asia are currently being “depressed” by delays at the Panama canal, which have increased the cost of shipping to the region from the US, analysts told S&P Global.

The IEA has stated that the wave of new LNG projects on the horizon “raises the risk of significant oversupply” as the world heads towards net-zero.

Citing Rystad Energy analysis, Semafor’s climate and energy editor Tim McDonnell noted that the world is heading towards an LNG “supply glut”, potentially rendering new US export terminals unnecessary. He said:

“If every global LNG project under consideration now were to be built, the market would be oversupplied by 2028 and for the foreseeable future after that.”

He added that, if the world does not manage to ramp up renewable energy production to the level required to tackle climate change in the coming years, the world could be undersupplied with LNG by 2030, based on currently planned projects.

How will the supply of US LNG affect global greenhouse gas emissions?

The pause on new LNG infrastructure was widely framed as a boost for US climate policy. (Many outlets said “climate activists” were the chief beneficiaries.)

Indeed, the Biden administration cited “the climate crisis” as a key factor motivating its decision.

Nevertheless, some commentators and business groups have argued that pausing the construction of new LNG terminals will, in fact, lead to higher emissions.

“The US should not undercut our allies or fund our enemies with a policy that will increase global emissions,” said Karen Harbert, chief executive of fossil-fuel lobby group the American Gas Association, in a statement.

When it is burned, the gas that could be exported each year via US LNG terminals that are currently under construction would result in emissions of 198m tonnes of carbon dioxide (MtCO2), according to Carbon Brief analysis of GEM data.

This would be equivalent to around 4% of annual US emissions – or the total amount emitted by Ethiopia.

If all the other US LNG terminals under consideration were built, these potential emissions would increase to 704MtCO2 – equivalent to roughly 17% of US annual emissions.

Crucially, however, stopping this new export capacity from being built would not automatically cut emissions by the same amount.

The final impact on emissions would depend on how the move affects gas prices in the US and in importing countries, how this affects the amount of gas being produced and consumer demand – and what would be used instead if less LNG is exported .

The Washington Post summarised much of the opposition to Biden’s policy in an editorial that stated the effect on overall emissions would be “likely marginal”. It said:

“You cannot change demand for energy by destroying supply: If the US did indeed curtail LNG exports, it would just drive customers into the arms of competitors such as Australia, Qatar, Algeria and, yes, Russia. Quite possibly, some potential customers would choose to meet their needs with coal instead.”

The fossil-fuel industry often argues against policies that curb supply on this basis – stating that consumers ultimately determine how much of their carbon-emitting products are used.

However, many studies indicate that despite “leakage” – where cuts in fossil-fuel supply lead to more being pumped elsewhere – curbing supply still reduces overall emissions.

At the same time, the UK government’s Climate Change Committee (CCC) noted in 2022 that increases in North Sea oil and gas production would raise global emissions, even if UK production was cleaner – and even if higher supply only boosted global demand fractionally.

A 2023 paper from the thinktank Resources for the Future concluded that removing a barrel of oil from global supplies resulted in emissions cuts equivalent to 40-50% of the total lifecycle emissions of that barrel.

The IEA says focusing climate policy efforts exclusively on supply or demand alone is “unhelpful and risks postponing – perhaps indefinitely – the changes that are needed”.

In order to achieve both existing climate pledges and the 1.5C target, the IEA therefore emphasises the need for “a wide range of different policies…to scale up both the demand and supply of clean energy and to reduce the demand and supply of fossil fuels and emissions in an equitable manner”.

(In a separate report, the IEA finds that onshore wind and solar power are now cheaper to build than both gas and coal power in virtually all circumstances, globally.)

One key pro-LNG argument is that US gas produces fewer emissions overall than other fossil fuels. Therefore, if it displaces Russian gas – supplied by pipelines that leak large amounts of methane – or high-emitting coal, then it will lead to lower global emissions.

This ties into a wider debate about whether gas can and should serve as a “bridge” or “transition” fuel between coal and low-carbon electricity. The US itself has reduced CO2 emissions from its own power sector by switching from coal to gas.

However, US LNG’s environmental impacts compared to other fossil fuels is contested. Emissions from methane leaks and the energy used to liquify, ship and “regasify” gas traded around the world can add up, dampening – or even outweighing – the emissions savings of switching from coal.

A US government-commissioned study by the National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) showed that US LNG “will not increase greenhouse gas emissions from a lifecycle perspective” when replacing coal in Asian and European power systems.

However, it also showed that depending on how and where the gas was used, there was a large range of potential emissions outcomes. For example, if US LNG is used to heat German or UK homes, it will not be replacing coal, just other sources of gas.

At the upper end of the range, LNG resulted in roughly 50% less emissions than coal in both European and Asian settings. However, at the lower end, US LNG resulted in roughly the same lifecycle emissions as coal, the study found.

Other studies have concluded that, in fact, gas can match coal in terms of emissions, given gas infrastructure can leak the powerful greenhouse gas methane. Research affiliated with NGO the Rocky Mountain Institute found that a methane leakage rate of just 0.2% puts gas “on par with coal”.

(It is worth mentioning that the Biden administration launched a suite of new standards and monitoring for the oil and gas industry at the end of 2023, which it says will prevent 58m tonnes of methane leaking from oil-and-gas infrastructure over the next four years.)

A study by Cornell University biogeochemist Prof Robert Howarth, frequently cited by climate activists, goes even further, stating that emissions from LNG are “27% to two‐fold greater” than using coal. However, this research – which has yet to be published in a scientific journal – remains contentious.

Even assuming that gas has significantly lower emissions than coal, given the limited remaining carbon budget, researchers have demonstrated repeatedly that all fossil fuels need to be cut rapidly in order to meet the global Paris Agreement temperature goals.

In the IEA’s net-zero scenario, which aligns with the Paris Agreement 1.5C target, new LNG infrastructure that is currently under construction is “not necessary”, according to the agency’s recent oil-and-gas report. (This is even before considering the additional capacity subject to the Biden administration “pause”.)

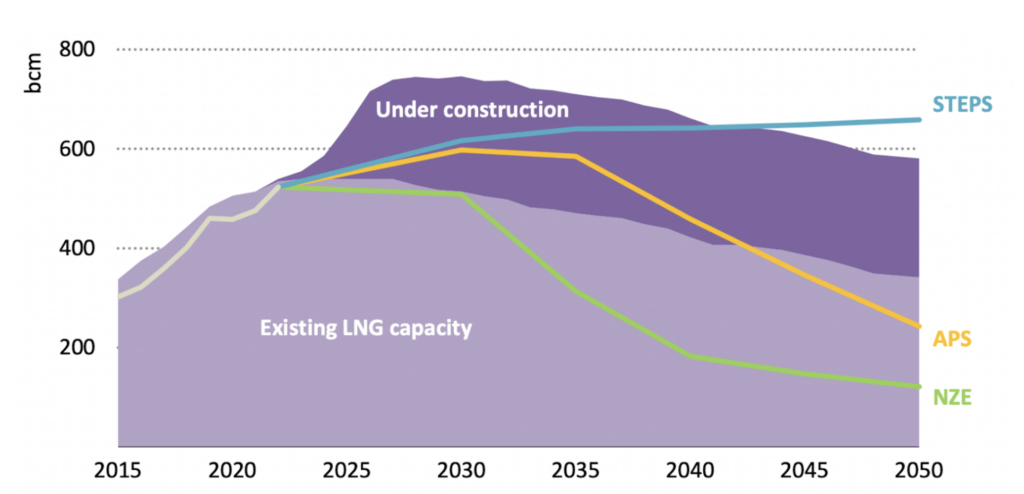

This can be seen in the chart below, with LNG needs in the net-zero pathway (green line) met by existing capacity. Even if countries meet – but do not improve on – current climate pledges (yellow line), much of the LNG capacity currently being built would not be needed.

In effect, permits for further new LNG export capacity – in the US or elsewhere – would only be required to meet global gas demand if international climate goals are missed by a wide margin. This is shown by the blue line in the figure below, with the IEA’s “STEPS” pathway – representing current government policies – linked to warming of 2.4C this century.

This conclusion is echoed in a paper from 2022 led by Dr Shuting Yang of the Harrisburg University of Science and Technology, which concluded that “long-term planned LNG expansion is not compatible with the Paris climate targets of 1.5C and 2C”.

The analysis suggests that LNG could help to keep emissions in line with a 3C warming scenario, as it would somewhat curb the use of coal.

The researchers therefore describe LNG infrastructure as “insurance against the potential lack of global climate action to limit temperatures to 1.5C or 2C”.

On the flip side, there are concerns that building such infrastructure could “lock in” the long-term use of gas, at levels incompatible with the 1.5C or 2C targets.

Moreover, there are question marks over the extent to which additional gas exports would, in fact, be used to displace coal, given demand for the fuel is already falling rapidly in many of the countries taking US LNG imports.

In a post on LinkedIn, gas scholar Anne-Sophie Corbeau at the Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy noted that it would be harder for LNG to displace coal in Asia than it has been for domestic gas to do the same in the US, as it is more expensive:

“As for LNG displacing existing coal in south-east Asia, unless it’s very cheap or you have a mandatory closure of coal plants or high CO2 prices, this won’t be as easy as gas displacing coal in the US. Not the same price levels.”

NRDC analysis concluded that, even among Asian nations, “only a small amount of US LNG exports is contractually obligated to countries that currently have a large amount of current coal electricity generation or are rapidly expanding”. (This analysis did not account for the wider market impact of US LNG sales, which could have knock-on effects on coal use.)

How will the move affect US politics in the coming months?

The pause on new LNG approvals is expected to be in place for months, possibly until after the November US presidential election. During this time, the Department of Energy will conduct a review of the pending applications and this will then be open to public comment.

The move has already attracted criticism from Republicans and could emerge as a talking point as Biden gears up to face his likely rival for the presidency – Donald Trump.

Responding to the decision, Reuters quoted Karoline Leavitt, a campaign spokesperson for Trump, who called it:

“One more disastrous self-inflicted wound that will further undermine America’s economic and national security.”

(Restricting LNG export capacity would tend to keep a lid on US gas prices and boost its energy security. Nevertheless, if Trump wins the election, he can be expected to reverse the decision of his predecessor. After winning the recent Iowa caucuses, he told the crowd: “We’re going to drill, baby drill, right away.”)

The response from climate campaigners has been largely positive. Veteran activist Bill McKibben wrote on his blog:

“This is the biggest check any president has ever applied to the fossil fuel industry, and the strongest move against dirty energy in American history.”

Commentators noted that the Biden administration had likely made the decision in order to appeal to young people and members of the Democrat base who prioritise climate action.

This comes as polling suggests that many young voters are turning against Biden, a trend partly attributed to his stance on the conflict in Gaza. Writing in Heatmap, editor Robinson Meyer noted that “the administration seems to be hoping a pause on LNG approvals will help reverse that dismal momentum”.

After signing up to “transition away from fossil fuels” at the COP28 summit in Dubai, the decision also sends an international message that the world’s largest oil-and-gas producer is taking action. “The pledge…was given actual meaning by Biden’s move,” McKibben wrote.