Q&A: The impact of farmer protests on the EU’s upcoming parliamentary elections

Orla Dwyer

03.19.24Orla Dwyer

19.03.2024 | 3:41pmThe agriculture sector holds a lot of power within the European Union, receiving around one-third of the bloc’s total budget.

But, amid rising production costs and lower incomes, farmers have been voicing their frustrations on streets across the EU over the past few months.

These protests have resulted in promises for more funding and loosened rules from both the EU and individual countries.

Agriculture has become a “particularly sensitive subject” among EU politicians ahead of the European parliamentary elections in June, says Politico.

Earlier this month, Carbon Brief travelled to Amsterdam and Brussels to discuss these issues as part of a reporting trip organised by Clean Energy Wire, an EU-focused news service for climate and energy journalists.

Reporters spoke to academics, policymakers and farmers about the upcoming European elections and the future of farming across the bloc.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief explores what these elections could mean for EU agricultural policy, the impact of the recent farmer protests and the possible pathways for farming in Europe.

- How important are climate and farming in the European parliament elections?

- What concessions have been made in response to the EU farmer protests?

- What does the future look like for EU agriculture?

How important are climate and farming in the European parliament elections?

The European parliamentary elections occur every five years. Voters across the EU will head to the polls over 6-9 June to elect 720 members of the European parliament (MEPs).

Each EU country is allocated a certain number of seats in parliament based on population size, from a minimum of six MEPs (Cyprus, Luxembourg and Malta) to a maximum of 96 (Germany). Candidates in each country are elected based on proportional representation.

The centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) won 189 out of 705 seats in 2019 – the highest portion of any group. The Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA) boosted their number of seats from 50 in 2014 to 74 in 2019.

This so-called “green wave” was particularly notable in Germany, where the Greens/EFA received more than 20% of the vote.

Climate change and the environment were key issues for voters in 2019, according to Eurobarometer surveys after the elections. Agriculture, on the other hand, was not listed as a main priority issue for people casting their ballots across the bloc.

Analysis of opinion polls and previous EU election results by the European Council on Foreign Relations, a foreign and security policy thinktank, suggested that this year’s results will “see a major shift to the right in many countries”.

The analysis, released in January, said that anti-European populist parties could top the polls in nine countries, including France, Italy and Poland. They could rank second or third in other places, such as Germany, Spain and Sweden.

Similar polls emerged ahead of the last election.

In the early days of 2019, Der Spiegel reported that public opinion researchers “believe that right-wing populists could end up with 20% of the EU-wide vote”.

These parties made gains in some countries in 2019, including Hungary, Italy and France, but, as the Guardian noted after the election, “a promised populist surge turned out to be more of a ripple” across the EU.

Recent analysis from the Jacques Delors Centre, a European thinktank, suggests that the “notion of a broad green backlash” in this year’s parliament election is “largely overblown”.

Based on an online survey of 15,000 people in Germany, France and Poland, they found that the majority of voters want more ambitious climate policy and would support “a raft of concrete measures” to cut emissions.

But a “sizeable minority” of people said they are against more ambitious climate policies – around 30% of people surveyed in Germany and Poland and 23% of those surveyed in France.

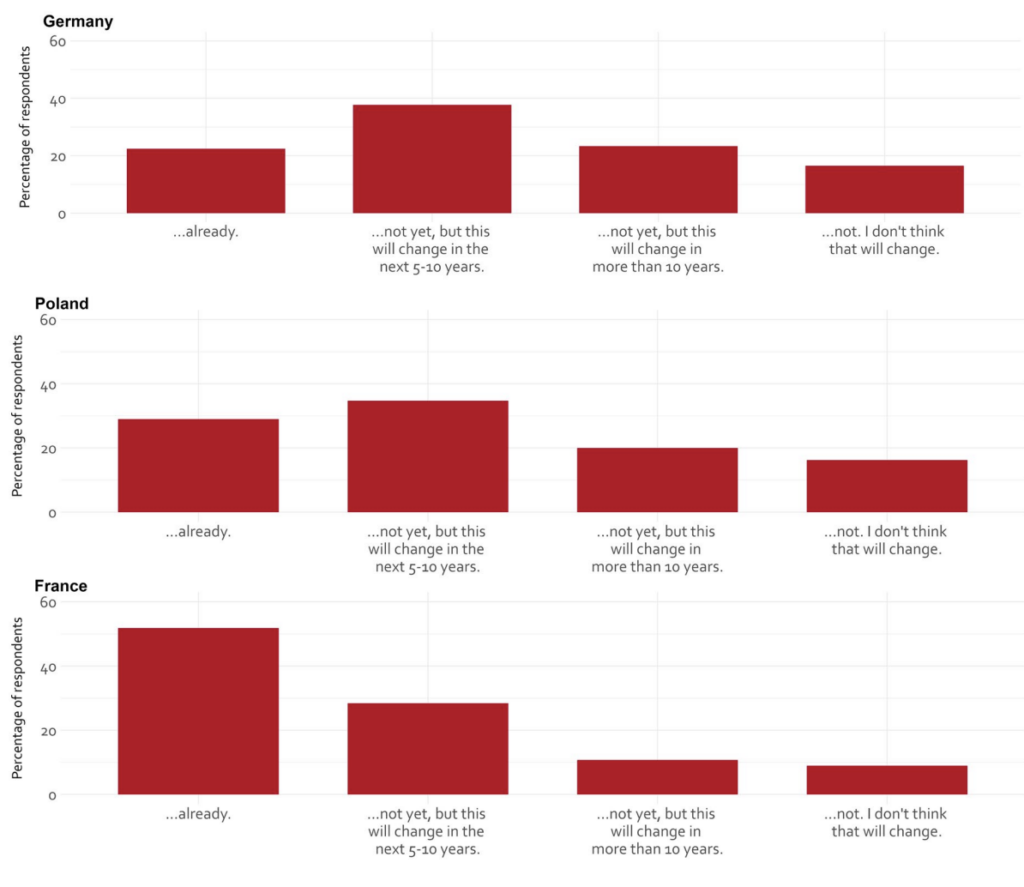

The chart below shows the percentage of people in each country who believe that the negative effects of climate change already affect them and their family, will do so in the future or will not affect them at all.

Rightwing parties have seen an increase in support in some recent national European elections. In Portugal’s parliamentary elections earlier this month, the centre-right won and support for the far-right also surged, the Financial Times reported.

There are a wide range of other votes happening in Europe this year, including legislative elections in Austria and federal elections in Belgium.

In the Dutch general election last November, the far-right Party for Freedom (PVV) won the highest number of seats in parliament. Coalition talks have been strained, with unresolved issues around finance and policy differences dividing the parties, but discussions remain ongoing.

The party gained support by “harnessing widespread frustration about migration”, according to BBC News. The housing crisis was also a key issue for voters, while farmers and people living in rural areas were concerned about proposed nitrogen-reduction plans.

Following a court ruling in 2019 that previous plans to tackle nitrogen emissions were not sufficient, the Dutch government re-developed these plans. In 2022, the government set targets to cut nitrogen pollution by as much as 70% in some parts of the country by the end of this decade.

Most of the country’s nitrogen emissions come from livestock and the construction sector and a voluntary “buy-out” scheme for farms is among the measures aimed to cut emissions. This would compensate farmers who choose to close their farms if they are located near nature reserves.

Protests kicked off in 2019 in response to the possible nitrogen-reduction measures and demonstrations have continued over the past few years. These frustrations were among the reasons the populist Farmers-Citizen Movement (BBB) won the biggest share of seats in the Dutch provincial elections last March.

This party was set up in 2019 after a surge in farmer protests over nitrogen-reduction plans and fears of the impact they would have on farming.

Months out from the European parliament elections, it is still unclear how these issues will affect the final results.

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen has voiced support for farmers in her campaign to continue leading the commission. She recently said that her party, the EPP, “will always be by the side” of farmers.

The Guardian reported that von der Leyen “has made climate concerns a lower priority” since announcing the re-election bid in February. But the EU’s climate commissioner, Wopke Hoekstra, recently told Politico that the bloc must “focus just as much, and probably more” on climate action in the years ahead.

Hoekstra’s comments followed a climate risk report from the European Environment Agency that outlined the “major challenges” the continent faces from extreme heat, drought and floods.

Bas Eickhout, a Dutch MEP in the Greens/EFA party, tells Carbon Brief that he believes the next parliament’s five-year term is “quite crucial, [with] this rise of right-wing populism and, at the same time, the attacks on the green deal” – the EU’s climate policy package.

Mohammed Chahim, the vice-president of the Social and Democrats Group and another Dutch MEP, tells Carbon Brief that he is “very concerned” about the future strength of EU environmental policy, but believes that parties can “find common ground under which we can continuously improve competitiveness” for farmers at the same time.

What concessions have been made in response to the EU farmer protests?

Since the end of last year, farmers have been protesting in several countries across the EU.

The protesters have many concerns, including competition from cheaper imports, environmental regulations and the rising costs of energy and fertiliser.

The complaints from farmers differ from country to country, as highlighted in Carbon Brief’s recent analysis of the key demands from farmer groups in 12 countries.

Many relate to environmental issues such as climate change, biodiversity and conservation, but others relate more to trade policy. Farmers in several countries are protesting against proposed measures, such as a trade agreement that is still being finalised between the EU and several South American countries.

In some countries, protesters are calling for more action on climate adaptation. For example, in Greece, farmers are asking the government to implement measures to prevent farmland from being damaged by flooding and other extreme weather.

In other countries, farmers are calling for fuel subsidies to continue and for fertiliser and pesticide restrictions to be reconsidered.

In several eastern European countries, farmers have raised concerns about Ukrainian grain imports. Farmers in countries surrounding Ukraine have been arguing for months that they “can’t compete” with the price of these imports.

The protests in France were largely halted in February after the government promised more “cash support” and withdrew a planned agricultural fuel tax increase, said Le Monde.

The French government also suspended national efforts to halve the use of pesticides by the end of this decade, the Daily Telegraph reported, which environmentalists described as a “major step backwards”.

On 31 January, the European Commission pushed back rules requiring farmers to set aside some land for biodiversity. This measure, which was due to take effect this year, was postponed.

Earlier this month, the commission proposed to review some terms of the EU farmer subsidies, including making this now-postponed land measure voluntary instead of mandatory when it takes effect.

The review is aimed to reduce paperwork for farmers and allow “greater flexibility for complying with certain environmental conditionalities”, the commission said.

Von der Leyen said in a statement that the EU’s agricultural policy “adapts to changing realities”, but continues to focus on “the key priority of protecting the environment and adapting to climate change”.

The commission president also scrapped a proposal to halve pesticide use.

This was an “absolute symbolic act” considering it was already “killed in parliament”, Dutch MEP Mohammed Chahim tells Carbon Brief. Last November, MEPs rejected the pesticide proposal, leaving it with an uncertain future.

What does the future look like for EU agriculture?

Agriculture generates around 25-30% of global emissions; in the EU, the figure averages about 10%. Global livestock emissions alone account for almost one-third of human-caused methane emissions, according to the UN Environment Programme.

At the same time, agriculture is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Drought can wither crops, extreme heat can kill livestock and floods can damage soil quality.

The EU has put forward plans to both reduce agricultural emissions and make the sector more resilient and sustainable for the future.

The “farm-to-fork” strategy, a policy plan forming part of the wider green deal, was proposed in 2020 as a way to make food systems “fair, healthy and environmentally friendly”. The plans under this strategy include measures to reduce fertiliser use, increase organic farming and provide more consumer information on “healthy, sustainable” food choices.

However, around half of the actions promised under this strategy have fallen by the wayside, Euronews reported on 19 February.

The next European parliament term will have a number of key agricultural issues to tackle including a reform of the Common Agricultural Policy, the EU farmer subsidy system, before 2027.

Earlier this year, the EU launched a “strategic dialogue” to bring together farmers, retailers and other stakeholders to discuss the future of EU agriculture. A report on the outcome of these talks will be given to the commission president this summer outlining a “common ground for the future of the union’s agri-food sector”.

Looking more globally, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization last year released a “roadmap” to change agrifood systems and end hunger without exceeding the 1.5C global temperature limit.

There is an “urgent need” to reform agrifood systems, the report said, in order to meet climate goals and improve food security.

It listed a number of global targets, including reducing livestock methane emissions by one-quarter by 2030, halving food loss and waste at retail and consumer level by 2030 and reaching net-zero deforestation around the world by 2025. A recent Nature Food comment piece criticised elements of this report.

Given that the future of agriculture is still being resolved on an EU and global level, Dutch MEP Bas Eickhout says it is not surprising to see farmers protesting over their concerns. He believes, however, that the protesting farmers “throwing manure on the street” are the “extreme voices” being amplified. He told Carbon Brief in Brussels:

“There are a lot behind who are not putting their manure here on the Berlaymont building. They are not happy, but they’re not protesting.”

He said that farmers need to receive more profits from the wider food chain, adding:

“[There are] a lot of producers, a lot of consumers and a couple in the middle that have the power. That’s where the profits are. There are enough profits in the food chain, but they are not ending up at the farms…[it is a] fundamental economic problem that is happening.”

John Arink, an organic farmer, recently spoke to Carbon Brief and other media outlets on his farm near the village of Lievelde, in the east of the Netherlands. (Read Carbon Brief’s Cropped newsletter from last week for more on Arink’s farm.)

He wants to see a future with less intensive farming and more outdoor space for animals to grow. He said:

“In Holland, we have some kind of a mantra that says the intensive way of producing milk and meat is very efficient. But it is not when you calculate all of the indirect dues of materials and energy, it shows that the intensive way of farming is very inefficient.

“Maybe from the financial point of view it can be efficient, but we have to look at it in the ecological way. And from that point of view, it’s very inefficient to produce so intensively.”

Carbon Brief attended a research tour with 16 other journalists as part of researching this article. Clean Energy Wire organised the trip and paid for travel expenses in Brussels and Amsterdam, but had no editorial involvement in this article.

-

Q&A: The impact of farmer protests on the EU’s upcoming parliamentary elections