Q&A: The global ‘trade war’ over China’s booming EV industry

Multiple Authors

08.28.24Multiple Authors

28.08.2024 | 5:00pmChina’s “new energy vehicles” (NEVs) have been the centre of media and geopolitical attention in recent months.

NEVs is a Chinese term and includes battery-electric (BEVs), plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs) as well as fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEVs).

According to data from China Customs and industry associations, the vast majority of Chinese NEVs being produced, sold and exported are BEVs and PHEVs. In this article, BEVs and PHEVs are referred together to as “EVs”.

In 2023, more than half of the EVs on the world’s roads were in China, pushing China to be the world’s largest EV market and producer. This rapid growth has largely been fuelled by the Chinese government’s support.

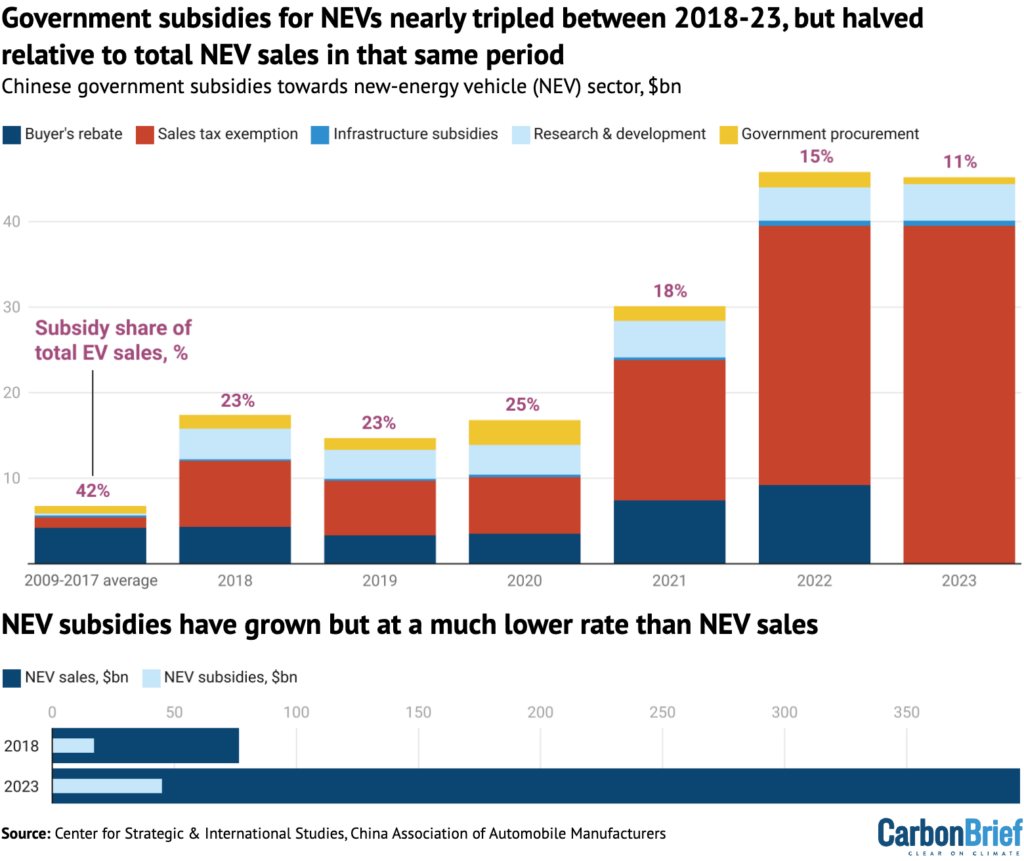

From 2009-2023 – in addition to strong policy support – the Chinese government poured an estimated $230bn into the industry, with this rate accelerating nearly three-fold over the past five years, even as some subsidies ended.

As a result, NEVs accounted for around 51% of all cars sold in China in July 2024, according to industry data. Carbon Brief’s analysis finds that 88% of China-made NEVs were sold domestically in 2023.

However, production has outpaced demand. The Paper, a state-affiliated newspaper, says that, except for a few leading brands, such as BYD, most Chinese EV makers produced a lot more cars than they could sell last year.

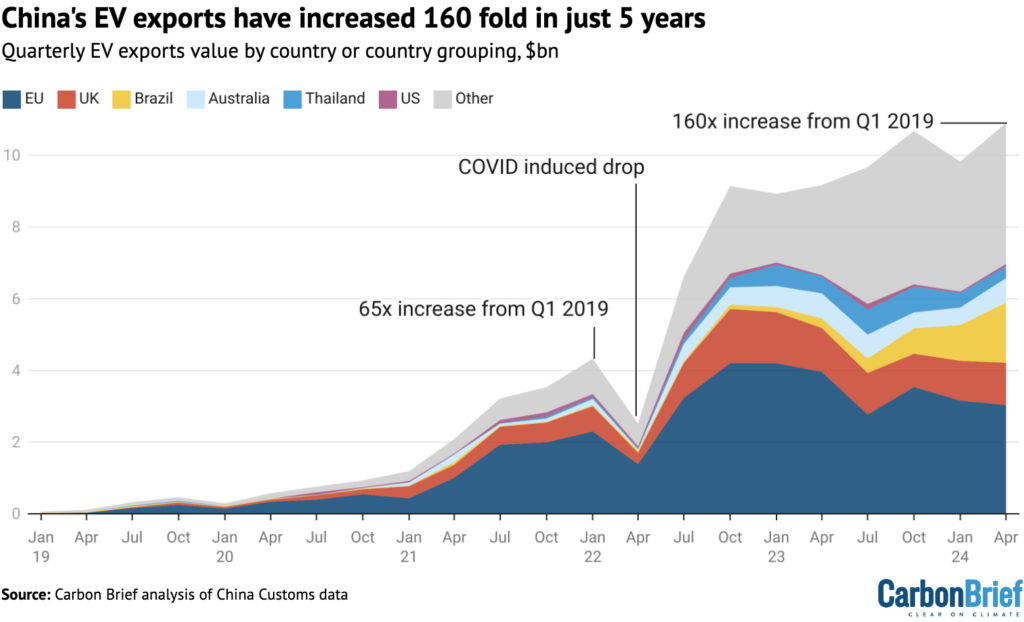

Meanwhile, EV exports from China – including foreign brands, such as Tesla – have increased 160-fold from 2019 to 2023, triggering fears of “overcapacity”.

In response, the EU, US and Canada have announced tariffs on China-made EVs, in what some publications have described as a “trade war”. To date, the UK – a leading importer of Chinese EVs since 2019 – has not announced any tariffs.

Chinese officials have strongly opposed these trade barriers, and launched “tit-for-tat” investigations into EU products. However, some in the industry have argued they will only be a “temporary setback” that will push firms to focus on other markets, such as Africa.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief looks at the Chinese EV industry, the history of its rapid growth as well as the support it received from the government. The article also explores whether it has an “overcapacity” problem, where the exports end up as well as why the US, EU and UK have adopted different trade strategies.

- How did Chinese EV grow so fast?

- How much subsidies did Chinese EVs receive?

- How many Chinese EVs have been sold?

- What is the ‘overcapacity’ debate around Chinese EVs?

How did Chinese EV grow so fast?

The Chinese EV industry is booming. In 2018, only 1.27m EVs were produced in China, according to data from China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM), but production in the month of October 2023 alone reached 2.8m.

There is a clear link between this rapid growth and Beijing’s national strategy to develop the EV industry.

According to a joint report by the International Council on Clean Transportation and China EV100, in the 1990s and early 2000s, there was a general recognition among China’s policymakers that, despite the growing demand for vehicles in China, the nation’s automakers were lagging behind their foreign counterparts. Becoming early innovators of EVs was seen as a way to establish a foothold in the industry.

In the 10th “five-year-plan for science, technology and education development” – a high-level development initiative for the period 2001-2005 – lithium-ion batteries and EVs are identified as the new development “focuses”:

“[China should] improve the overall technological level of industry…focusing on the development of raw materials and ancillary parts for lithium-ion batteries, lithium polymer batteries, and nickel-metal hydride batteries…focusing on the development of EV…[and] select a number of cities to implement clean fuel vehicle demonstration projects.”

(For more on Chinese policymaking, see The Carbon Brief Profile: China and Q&A: What does China’s 14th ‘five year plan’ mean for climate change?.)

The enthusiasm coincided with a broader push in the early 2000s for China to become an “innovation-oriented country” by 2020.

In 2008 and 2009, a number of local governments started to roll out electric buses across China and purchase EV fleets instead of combustion-engine cars. Some cities, such as Hefei and Changzhou, made it easier for EV buyers to get licence plates – making purchasing EV more appealing to the general public.

Meanwhile, global competition and cooperation also assisted the rise of Chinese EVs. A 2023 report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a US-based thinktank, notes that some Chinese EV makers had purchased western brands and increased their presence in the markets by using these western brands’ established reputations. For instance, state-owned company SAIC purchased Britain’s MG and Geely acquired Volvo via a deal with Ford.

By now, these Chinese firms were providing some of the key technologies for their western partners. Mercedes-Benz, for example, relied on Geely to “completely revamp” its Smart brand – one of the latest European brands to shift production to China – whose new electric sport utility vehicle (SUV) model is produced in Zhejiang province, says CSIS.

In recent years, the intensified competition has also pushed Chinese companies to innovate, developing cutting-edge designs, for example, EV batteries.

Jacob Gunter, lead economic analyst at thinktank MERICS, tells Carbon Brief that Chinese EV batteries have “not only come at a discount, but also are available in much higher quantities because the manufacturing capacity has been built out in China and continues to be built out”.

While China’s dominance in the global EV industry is now clear, there are differing views as to how it got there. Yao Zhe, global policy advisor for Greenpeace East Asia, tells Carbon Brief that “the Chinese view [their success] as a result of ‘the market’”, while the US and EU puts it down to “government stimulus”. She says:

“The industry in China has made significant progress in battery technology and reducing manufacturing costs. And, equally important, Chinese consumers have a higher preference for EVs.”

Nevertheless, Yao also acknowledges that monetary support, including subsidies, has helped “create economies of scale” for China’s EV industry, which is “important for early-stage clean technologies”.

How much subsidies did Chinese EVs receive?

It is not uncommon for governments to provide monetary support to their EV industry. The UK, for instance, has announced £49m in government funding to support “development of low carbon emission technologies for vehicles”.

But the scale of support in China has been very large, including both direct and indirect subsidies to the producers, the “national buyer rebates” for consumers, as well as other support.

Between 2009-2023, Beijing poured at least $230.8bn into supporting the industry, according to calculations by CSIS. (It says this figure is a conservative estimate, as it excludes some types of policy support.)

Some $60.7bn of this was issued between 2009 and 2017, when the industry “was just getting off the ground”, according to CSIS. This came partially in the form of direct subsidies, including for research and development, for EV components and materials, as well as, in some cases, investing into EV companies directly.

However, the total value of direct subsidies, excluding regional support, has nearly tripled over the past five years. In 2018, the total subsidies for the EV sector were $17.4bn, while, in 2023, it soared to $45.3bn, according to data from CSIS.

Meanwhile, the government has also given “indirect” support to the industry. As EV manufacturers are considered “high-tech companies”, they are subject to lower corporate tax rates. As a “strategically important industry”, they are able to access low-interest loans, as well as low-cost land and electricity.

Last month, China’s top economic planner the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) issued a new policy to raise the subsidy for car owners who “trade-in” old vehicles for EVs. Owners giving up combustion cars can receive 20,000 yuan ($2,766).

Professor Pan Jiahua, vice-chair of the national expert panel on climate change of China, told Carbon Brief earlier this year that China viewed EV subsidies as a “natural” approach to growing a nascent industry. He said:

“[An industry is] like a plant – in the very beginning when it’s a seed then you need to take care of it. But when it grows and becomes mature, then it can stand on its own and be competitive.”

This is reflected in the shift in the Chinese government’s approach from 2016. Discovery of significant fraud in local-level subsidy schemes prompted the scrapping of the old model, which gave local governments “considerable runway to set their own subsidy levels and eligibility requirements” for the EV industry. It was replaced with a “dual credit” programme, which has been described as a “more market-oriented system”.

In 2023, the Chinese central government scrapped up-front EV purchase subsidies known as “national buyer rebates”, which had contributed around 20% to the total subsidies in 2022.

Nevertheless, even with the ending of the national buyer rebate, the overall amount of subsidies remained steady in 2023, as shown in the figure above.

This is because the value of sales tax exemptions for purchases for NEVs – EVs as well as FCEVs (although significantly smaller amounts) – has surged as a result of the booming market, offsetting the end of upfront purchase subsidies. As shown above, the total subsidies offered to NEVs in 2023 ($45.3bn) were only 1% lower than 2022 ($45.8bn).

While subsidies have increased in absolute terms since 2018, total NEV sales have grown at a much faster rate over the same period, meaning that subsidies now make up a far smaller share of the value of NEV sales.

Shown in the lower half of the chart above, subsidies of around $17.4bn in 2018 were equivalent to 23% of the value of total NEV sales. By 2023, subsidies climbed to $45.3bn, but were only equivalent to 11% of the value of sales. Between 2009-2017, aggregate government subsidies had been equal to a 42% share of the value of total NEV sales.

Total subsidies could continue to reach record highs if sales continue to surge, because of the sales tax exemption. (Sales tax exemptions, also known as the “purchase tax exemption”, are expected to be phased out in 2027.)

Gunter tells Carbon Brief that, while central government EV subsidies have now “mostly gone away”, there is still indirect support including tax credits and cheap loans. He says:

“You still have indirect subsidies, such as the 100% R&D expenditure tax exemptions…and state-run banks [providing] cheap loans. But, in terms of the really big subsidies that Beijing pushed out in the early-to-mid stage of their industrial policy…that’s mostly gone away.”

How many Chinese EVs have been sold?

Policy and subsidy support from the Chinese government has helped the sales of EVs in China to rise rapidly.

According to the China Passenger Car Association (CPCA), a trade association, NEVs exceeded 51% of cars sales in China in July 2024, representing a nearly 37% year-on-year increase.

Shown in the chart below, the sales of NEVs (blue) have grown rapidly, overtaking those of combustion-engine vehicles (grey) last month.

In 2023, about 60% of the world’s EVs were sold in China, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Meanwhile, the price of NEVs for Chinese consumers has also been pushed to a new low.

According to data from NDRC, compared to January, NEV prices in China in April were down 5-10% to 18,000-299,900 yuan ($2,479-$41,306) per unit.

Gregor Sebastian, a senior analyst at US-based consulting firm Rhodium Group, tells Carbon Brief that EVs are sold at “extremely low prices” to attract domestic customers, but there is a limit on how many EVs the domestic market “can absorb”.

The next step for EV makers is the “need to find [the] overseas market to export them”, adds Sebastian.

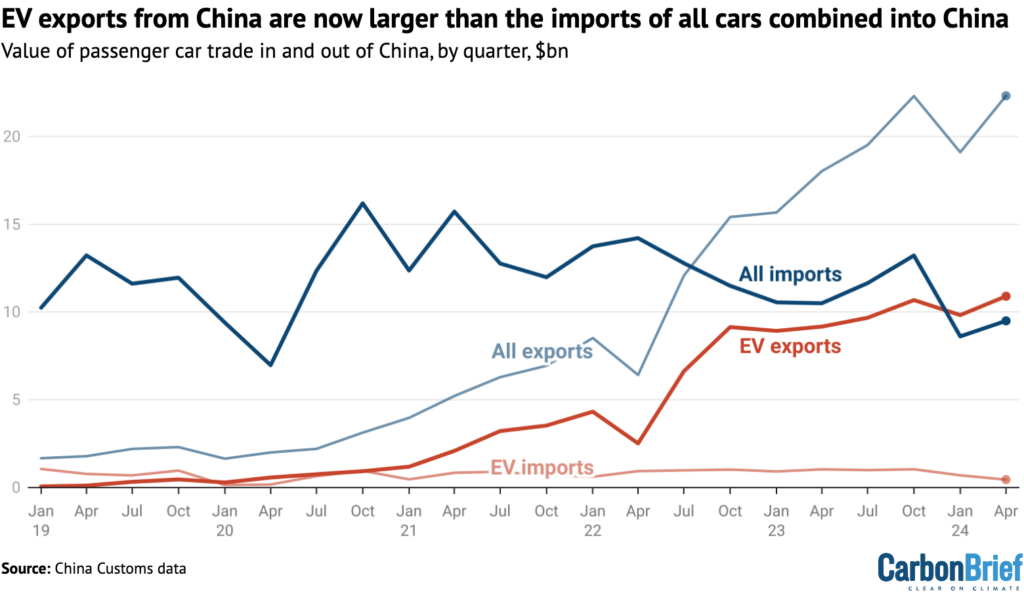

According to data from China Customs, shown in the figure below, the value of Chinese EV exports (thick red) has increased 160-fold in the five years since 2019.

The exports of all passenger cars (thin blue) surpassed the import of all passenger cars (thick blue) in 2022. By comparison, imports of both EVs (thin red) and all passenger cars (thick blue) remained flat.

The only dip in China’s EV export growth came in the beginning of the second quarter of 2022, when China’s manufacturing hub Shanghai – the location of Tesla’s gigafactories – entered a strict Covid-19 lockdown.

The figure below shows the top destinations for Chinese EV exports. In cumulative terms, the UK (red) has imported more Chinese EVs than any other country since 2019, though the EU, as a bloc, is larger (dark blue). In June, Chinese manufacturers accounted for 11% of the EU’s EV market, according to Bloomberg.

The other three largest importers since 2019 are Brazil (yellow), Australia (light blue) and Thailand (mid blue).

In contrast, the past five years of exports to the US (purple) were minimal, even before the country imposed a 100% import tariff on China-made EVs in May.

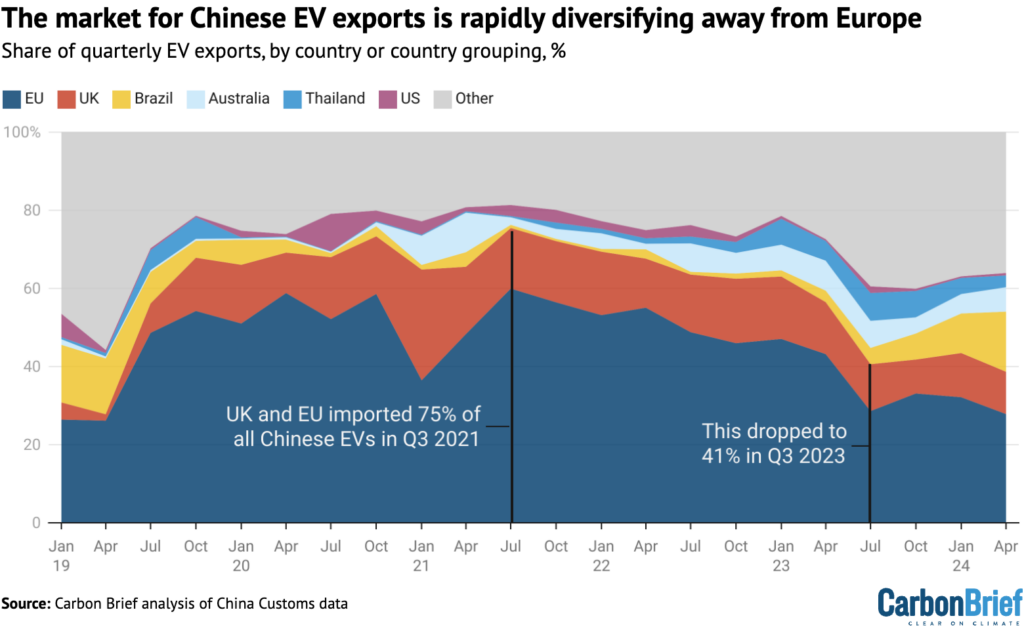

Despite the steady rise in the absolute value of Chinese EVs exported to the EU and UK, the percentage share of exports to these two destinations has decreased significantly in recent years, as the destinations for EV exports have diversified.

As shown in the figure below, the combined EU (dark blue) and UK (red) share of Chinese exports dropped from 75% in 2021 to around 40% in 2023.

In contrast, other export destinations – including Brazil (yellow), Australia (light blue) and Thailand (mid blue) – grew from about 22% in the first quarter of 2023 to 40% in the same period in 2024.

In April, Reuters reported that Brazil overtook Belgium – a key entry point for the EU market – as the top export market for Chinese EVs.

Nevertheless, Carbon Brief’s analysis, based on data from CPCA, finds that only 12% of China-made NEVs, including FCEVs, were exported in 2023, with 88% of NEV production sold domestically.

In comparison, Germany, the third largest car exporter in the world behind China and Japan, exported 250,000 of the 308,000 cars – both combustion engine vehicles and EVs – it produced in May 2024. This corresponds to around 81% of production being exported.

Furthermore, CSIS shows that only around 50% of the EVs exported from China in the first half of 2023 were produced by Chinese companies. Some 39% – the largest share – were produced by Tesla. Other joint ventures between western and Chinese companies accounted for another 9.5% of exports in 2023, says CSIS.

In an analysis, Sebastian, along with CSIS senior fellow Ilaria Mazzocco, has written that this illustrates the “dilemma” facing developed countries:

“[This] reflects the dilemma facing traditional automotive-exporting countries in balancing the interests of domestic companies and fending off the risk of deindustrialisation and overreliance on concentrated supply chains [on one hand] with the need to electrify the transportation sector to meet decarbonisation targets [on the other].”

Meanwhile, the Chinese government has been accused of providing an “unfair” advantage for its own brands via supplying large subsidies that enables them to sell EVs at significantly cheaper prices than their rivals around the world.

Combined with the rapidly rising exports of Chinese EVs, these concerns have led to a fierce debate around “overcapacity” in recent months.

What is the ‘overcapacity’ debate around Chinese EVs?

“Overcapacity” has traditionally been used to describe where there are too many products – and too much production capability – chasing too few buyers.

The Paper, a state-affiliated newspaper based in Shanghai, reports the overall “capacity utilisation rate” – the ratio of actual “output” to “production capacity”, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics – of NEVs last year was between 57% and 76% in China.

(A separate report from the Paper says “overcapacity” of a product occurs when the “capacity utilisation rate” is below 79%”, which means less than 79% of the manufactured products were used or consumed.)

In 2023, the rates for EV makers Nio and Guangzhou Xiaopeng (known as XPeng) were below 50%, according to the Paper, while only a few leading brands, such as BYD and Tesla, achieved a rate of more than 90%. This means most Chinese NEV makers were producing a lot more vehicles last year than they could sell, which increased the chance of “overcapacity” across the whole NEV industry.

However, Yao tells Carbon Brief that the current “overcapacity debate” is driven by the US and other western economies’ concerns about “China’s dominance” in the “clean-tech industry”. She adds:

“The market is never in perfect equilibrium, so overcapacity is almost a periodic phenomenon. But it is much more complicated to say whether or not there is a problem of overcapacity in practice than in theory.”

Kyle Chan, author of the High Capacity newsletter, has argued that there are two competing worldviews driving the overcapacity debate.

One view is that China’s “production of more than its fair share of certain goods”, boosted by “unfair state support”, contributes to overcapacity. The other, Chan explains, is that “everybody benefits” from competition, especially consumers and, in the case of low-carbon technologies, that is a “big win for the planet”.

Chan adds that the argument is essentially about “jobs and a sense of what’s fair”.

“The overcapacity issue only comes up for certain types of goods tied to certain types of jobs”, says Chan, and nobody accuses China of creating overcapacity in the “clothing or toy or smartphone manufacturing” sectors.

Yao says the argument from the EU and US around the “unfair” competition in the EV industry is a “tactic to gain time for their own domestic industries in the race”.

Both the US and the EU have implemented tariffs to limit the impact of Chinese EVs on their home markets and domestic manufacturers.

On 26 August, Canada announced it will impose a 100% tariff on China-made EVs, following the US and EU. The UK, a top importer of Chinese EVs, however, has not announced any measures – and reports to date suggest it may not do so.

Nevertheless, Carbon Brief’s analysis shows EVs “are an important part” of limiting global warming to “well-below 2C or 1.5C”.

An analysis by Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst from the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, says China’s goal of raising the share of NEVs sales in total vehicle sales to 45% by 2027 provides an “opportunity” for China to meet its climate goals.

With the sales of NEVs now surpassing 51% in July, the country could achieve its own climate targets earlier than initially pledged.

Why did the US impose tariffs?

In May, the US increased tariffs on China-made EVs from 2.5% to 102.5%.

President Joe Biden explained that the US tariffs are a response to China “cheating” and the resultant “damage here in America”. In a statement, the White House said “extensive subsidies and non-market practices leading to substantial risks of overcapacity” was the main reason for the decision.

Joseph Webster, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, a US-based thinktank, tells Carbon Brief that, “in order to level the economic playing field, the US is levying these tariffs” and “there’s also an interest in maintaining the strategic industrial capacity in the US and elsewhere”.

Last month, Reuters reported that the US may also “impose limits on some software made in China” for EVs. Washington has already targeted nearly the whole supply chain of EVs, which includes batteries and semiconductors.

This is a reflection of Chinese EV components entering into the US via the US-Mexico-Canada free trade zone, says Webster, despite the US not being a big receiver of Chinese EVs.

According to Webster, lithium-ion batteries also have military applications, as he explained in a recent article for national security outlet War on the Rocks. He says this may have been a further consideration when the US administration was deciding on EV tariffs. Webster wrote:

“Batteries, often overlooked, could quietly tilt the balance of military power…Batteries have military implications, creating difficult tradeoffs for policymakers balancing strategic, economic, and decarbonisation priorities.

“While mainland China’s lithium-ion storage batteries are useful for meeting economic and decarbonisation goals across the US, Europe, and elsewhere, its battery complex poses potential security risks.”

An additional concern is the potential for internet-connected vehicles to be used for real-time surveillance, Webster says. He explains: “It’s not a huge [leap of] imagination to think that these vehicles can be used for surveillance purposes”, considering “China has a long history of hacking everything, everywhere, all the time”.

What are the EU’s measures?

The EU proposed provisional duties on Chinese EV, which are set to become definitive by November if member states back the measures as expected. In July, the provisional duties came into force, despite Beijing calling on Brussels to “scrap” them.

Different rates are applied to different automakers, following the result of an earlier investigation. For instance, state-affiliated SAIC faces tariffs of 38.1%… with the investigation, receives 17.4%, according to the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post.

Jacob Gunter at MERICS tells Carbon Brief that, in his conversations with EU policymakers, they were “very proud of the fact that, at every step in this process…[their actions] fell under World Trade Organisation (WTO) compliance”, which includes implementing different tariff rates to different Chinese EV companies.

The objective, as European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen explained, “is to engage China and get Beijing to course-correct and address the problems at their root”.

Gunter believes the tariffs are not “intended to fully block all Chinese EV imports into Europe”, but “are meant to try to mitigate and block the distortions coming from the whole industrial policy subsidy package from China, and [EU policymakers] have a pretty expansive definition of that”.

Belinda Schäpe, China policy analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), tells Carbon Brief that the EU will have to balance the economic interests of its manufacturers against the need to meet its climate goals. She explains:

“The question remains what exactly the EU’s long-term goal is in balancing priorities for economic and climate security. The European car industry is at the heart of Europe’s industrial power, but it has also overslept on the electrification trend…If Europe doesn’t want a large share of Chinese EVs, the question arises where the EVs on Europe’s roads from 2035 will come from – and, perhaps more importantly, who will be willing to pay the premium?”

Daniel Gros, the director of the Institute for European Policy-Making at Bocconi University, has argued in an article for Project Syndicate that a key driver behind the difference between the US and EU’s approach is that “the US is so fixated on its geopolitical rivalry with China that it has effectively closed its market to green Chinese products”, while the EU “does not have as dominant a position to lose”.

“That’s a very different policy [approach] than the US”, according to Webster. He argues that “the probability of the US accepting large-scale EV investments from China is very low and substantially lower than Europe.”

What is the UK’s attitude?

Despite the change in government in July, UK policy on Chinese EVs has – so far – remained consistent. Former Conservative transport secretary Mark Harper responded to concerns about Chinese EVs “flooding” the UK market by emphasising that the country’s “robust” legal structure “will make sure that competition is fair and that there’s a level playing field”.

Both new current trade secretary Jonathan Reynolds and chancellor Rachel Reeves have signalled that they are not currently considering implementing EU-style tariffs.

“I am not ruling anything out, but, if you have a very much export-oriented industry, the decision you take [has to be] the right one for that sector,” the Financial Times quotes Reynolds saying.

However, a Times commentary by the newspaper’s economy editor, Mehreen Khan, argues that this decision limits the UK’s ability to avoid a “pernicious dependency” on Beijing.

She adds: “If there are simply not enough buyers for Chinese wares, then, at best, tariffs could force Beijing into an economic rebalancing that it is unwilling to voluntarily undertake.”

An article from the Economist thinks the “main motivation” behind the UK’s strategy “is likely to be fear of retaliatory tariffs”. It says:

“China is a big export market for high-end producers like Rolls-Royce, Jaguar and Bentley, which make up a big chunk of Britain’s car industry. Losing the market for Chinese tycoons would hurt.”

What is China’s response?

China has strongly opposed the EU’s import duties.

The Chinese Ministry of Commerce filed an appeal with the WTO on 9 August over the EU’s imposition. The ministry said the EU’s “preliminary ruling lacks a factual and legal basis, seriously violates WTO rules and undermines the overall situation of global cooperation in addressing climate change”.

The Financial Times reported that the European Commission responded that it “was ‘carefully studying’ the details of the Chinese complaint” and would react “in due course, according to the WTO procedures”.

Meanwhile, the “escalated” trade dispute with the EU has led China to launch an “anti-dumping” investigation into European dairy products as a countermeasure. It is China’s third such probe, after brandy and pork, since the EU announced the tariffs.

Beijing has also called on the WTO panel to resolve a dispute over US subsidies for domestically manufactured EVs under the Inflation Reduction Act.

For its part, the WTO said last month that China has a “lack of transparency” on its industrial subsidies, citing this as a possible cause for the international concerns around “perceived” overcapacity.

Chinese manufacturer Neta Auto views the tariffs as a “temporary setback” – the growth rate of Chinese NEV exports in June dropped 20-30 percentage points – that will incentivise Chinese companies to explore other overseas markets, such as in Africa.

Xiaojian Wang, head of supply chain for Allchips, a Chinese electronic components distributor based in Shenzhen, tells Carbon Brief that separate US tariffs force the automobile chip industry to reduce “reliance on chip brands from Europe, the US and Japan” in favour of “domestic production of automotive chips”. He says:

“The US tariffs on Chinese semiconductors are expected to further accelerate this localisation process. Due to concerns about potential sanctions from the West, more Chinese EV manufacturers are likely to consider Chinese automobile semiconductors as a viable alternative.

“Many NEV manufacturers have their own power semiconductor department, as far as I know. BYD, for example, also owns plants for [automobile chip supply] in China to [meet its chip demand for NEV manufacture].”

Freelance climate journalist Henry Zhang contributed to this article.