Analysis: How will England’s strategies for trees and peat help achieve net-zero by 2050?

Josh Gabbatiss

05.19.21Josh Gabbatiss

19.05.2021 | 2:59pmPlans to plant millions of trees and restore swathes of peatland across England are at the heart of two new UK government strategies to boost biodiversity and tackle climate change.

The England Trees Action Plan and England Peat Action Plan are the latest documents detailing the nation’s efforts to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

Burning, grazing and draining have left only a fraction of English peatlands in their natural state, meaning they currently release as much CO2 as all industrial processes in the UK. Meanwhile, tree-planting rates are a long way off existing government targets.

While the new plans include various proposals for reversing these trends, key statements on peat restoration and tree planting largely reiterate previous government pledges.

The devolved administrations of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are responsible for their own trees and peatlands. Here, Carbon Brief has assessed the most relevant elements of the English plan and what they mean for the UK’s wider climate targets.

Sink to source

Despite having responsibility for around a tenth of the nation’s emissions, the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) has faced criticism for lacking a plan on cutting greenhouse gases.

Additionally, following a major revision to official data, the land-use sector – which is under Defra’s remit – has switched from being an emissions sink to a source.

This means rather than absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere, the nation’s fields, peatlands and forests are currently a net contributor to emissions.

Land-use emissions are often subject to considerable uncertainty, but this change was the result of improved analysis of emissions from degraded peatlands, which added 15-20m tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2e) annually to the UK inventory.

Wow OK, so the UK’s land sector is now a source, not a sink of greenhouse gas emissions

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) March 26, 2021

Needs to be a sink if UK is going to reach net-zero…

What happened? 🧵 pic.twitter.com/It660pPiiV

The Climate Change Committee (CCC), which is the UK government’s official climate advisor, says planting trees and restoring peatlands will be essential to meet the UK’s net-zero targets, especially given their capacity to offset emissions from “hard-to-decarbonise” parts of the economy, such as aviation. This means Defra’s role in cutting emissions is vital.

The new plans for England were announced by environment secretary George Eustice alongside new legally binding targets for species abundance.

Speaking at an event at Delamere Forest in Cheshire, Eustice said:

“The actions I have set out for peat, trees and species represent a huge step forward in our efforts to tackle the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss.”

Both strategies emphasise the importance of acting fast and “turbo charging” efforts following years of slow progress. “To respond to climate change, we need you to plant trees now,” the tree plan states.

In the short term, the main mechanism by which to do this is the relatively modest £640m Nature for Climate Fund, originally announced in the Conservative manifesto.

From 2024, the government wants its new Sustainable Farming Incentive, Local Nature Recovery and Landscape Recovery schemes to be the main means of public support.

All of these schemes are part of the replacement for payments under the EU Common Agricultural Policy. They are meant to reward farmers and landowners for producing “public goods” such as tree planting and peatland restoration.

Defra has also announced a separate scheme aimed at encouraging older farmers who are more resistant to “green” innovations to move out of the sector altogether.

As part of the wider strategy to encourage landscape restoration, both plans also propose expanding the newly launched UK Emissions Trading Scheme to cover nature-based solutions.

Tree planting targets

The tree plan states that the bulk of the Nature for Climate Fund – “over” £500m of the £640m – will go towards tripling annual tree-planting rates in England from their current levels by the end of the current parliament in 2024.

According to a government press release, this will mean planting “approximately 7,000 hectares of woodlands” by this date.

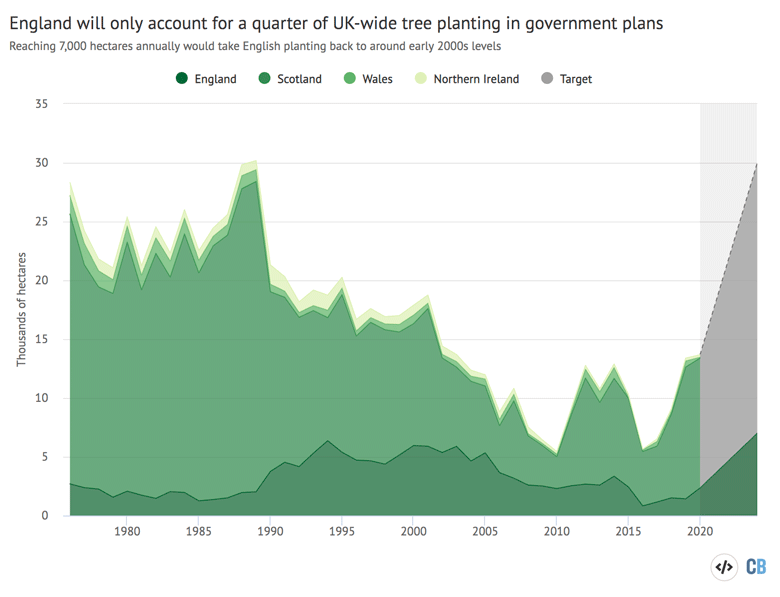

This announcement drew criticism from some campaigners who said it was a “rehash” of previous targets that would leave other devolved administrations doing much of the heavy lifting on the UK-wide goal of 30,000 hectares planted annually within three years.

The CCC has advised that the “net-zero by 2050” target requires 30,000 hectares to be planted annually from 2024, covering “at least 17%” of the UK’s land area and storing 14MtCO2e each year.

Andrew Allen, policy lead at the Woodland Trust, tells Carbon Brief he has not seen much coordination so far with other devolved administrations on how to achieve this national target, although the new plan pledges cooperation “to deliver a UK-wide step change in tree planting and establishment”.

The split between countries could have an impact on how much emissions are absorbed and over what timescale. Scotland is currently the only nation that is making significant progress with tree planting, mainly in the form of commercial plantations of conifers.

These trees grow and, therefore, absorb carbon faster than broadleaves, although there is evidence that native and broadleaf woodlands store more carbon in the long term.

Stuart Goodall, chief executive of the Confederation of Forest Industries (Confor), tells Carbon Brief that there is little to suggest in the new tree plan that there will be many commercial conifer plantations in England in the coming years. The document indicates the government will “predominantly” fund “native broadleaf woodlands”.

Building on existing targets, the tree action plan also alludes to a new “long-term tree target within a public consultation on Environment Bill targets, expected in early 2022”.

The new document also mentions funding for public and private sector tree nurseries and seed suppliers to “enhance quantity, quality, diversity and biosecurity of domestic tree production”, as well as a notification scheme to better manage supply and demand.

This is the first public investment from this government for the sector, despite its essential role in ramping up tree planting.

Other key measures with potential climate benefits include.

- The England Woodland Creation Offer will be launched in spring 2021. This grant is administered by the Forestry Commission and funded through the Nature for Climate Fund to support the creation of over 10,000 hectares of new woodland, including agroforestry. Landowners will be allowed to switch to new schemes, such as the Sustainable Farming Incentive, when they are ready.

- Encouraging timber use by developing a “policy roadmap”, providing “financial support to develop innovative timber products” and through public procurement of timber products. The CCC has outlined a small role for increased timber use in the UK’s net-zero strategy.

- Improving the data and modelling associated with woodland expansion and woodland management techniques and how they affect carbon flows, including in the UK’s greenhouse gas inventory.

- Expanding the nation’s forests managed by Forestry England and encouraging public bodies to plant trees.

- Introducing a new category of “long-established woodland” – woodlands that have existed since at least 1840 – alongside ancient woodland and consulting on the protections they are afforded in the planning system. Also updating the ancient woodland inventory to cover the whole of England.

Protecting peatlands

The peat strategy has been a long time coming, as it was originally pledged in the government’s 25 Year Environment Plan published in December 2018.

Peatlands store around 3bn tonnes (Gt) of carbon in the UK, three times as much as the nation’s forests, according to the British Ecological Society. However, as it stands, only 13% of England’s peatlands remain in a near-natural state.

While healthy peatlands absorb emissions, they release them when they are damaged. Draining, burning or grazing animals on peatlands can all turn them from carbon stores to emitters.

In their current state, English peatlands emit around 10MtCO2 each year, around the same as the UK’s industrial processes.

The government says it will spend just £50m from the Nature for Climate Fund on restoring around 35,000 hectares of peatland by 2025, a pledge originally made in the most recent budget.

This is just 5% of England’s total peat soils and 1% of the UK total. The CCC has recommended 50% of upland peat and 25% of lowland peat should be restored to achieve the net-zero target, cutting overall peatland emissions by 5MtCO2e by 2050.

Most peat restoration so far has been in upland bogs, whereas the majority of emissions come from lowland areas that are often used for farming. The plan says at least 15% of the area covered by the Nature for Climate Fund will be lowland projects.

By summer 2022, there will also be recommendations from a task force on how to sustainably manage these lowlands, the plan says. This could involve farmers selling carbon credits in return for improving peatland quality.

In an assessment of the strategy published by Friends of the Earth, CPRE and Plantlife, campaigners note the lack of “binding targets for peatland restoration”.

Guy Shrubsole, a campaigner at Rewilding Britain, tells Carbon Brief that his main issue with the peat plan is everything being “slower than necessary”, especially given the role of damaged peat in actively emitting carbon.

A key area of concern is the practice of rotational peatland burning, a management technique often used on grouse moors.

Burning peatlands releases 260,000 tonnes of CO2 each year. Eustice notes in an introduction to the plan that, while such emissions are “fairly low”, these practices can prevent peatland from recovering and acting as a carbon sink.

The government has been under pressure to end this practice. The CCC recommended a complete ban by 2020 and Natural England has said the practice is necessary only in “some very specific circumstances”.

Defra has already announced some measures to phase out burning of upland peatlands, while leaving various “loopholes” that environmental groups say mean only 9% of total peatland is covered.

Nevertheless, the government says 40% of upland peat falls under its burning ban and it will “keep under review the environmental and economic case for extending the approach”.

Another element of the peat plan that made headlines was the announcement of a consultation on banning the sale of peat compost for gardening.

Extraction for gardening takes up a “comparatively small proportion” of the UK’s peat area, according to a government report from 2017. It makes up just 4,600 hectares compared to the 145,000 hectares – mainly in Scotland and Northern Ireland – that have been used to obtain peat for fuel.

However, the new plan notes that two-thirds of peat sold in the UK is from Europe, meaning “we are effectively exporting our carbon footprint”.

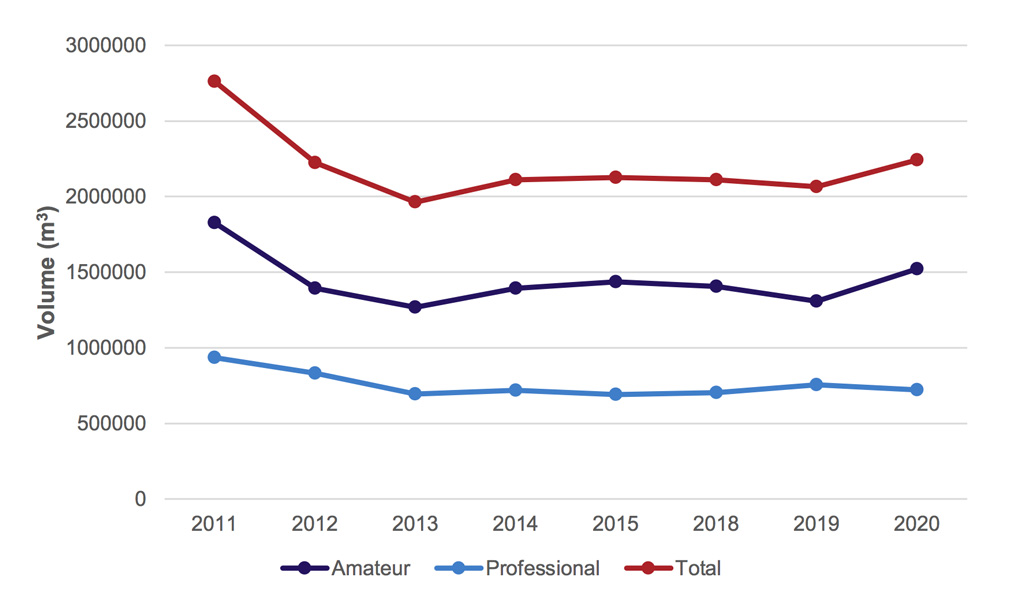

Voluntary targets set for peat sellers in 2011 to phase the material out by 2020 have had little impact, as the chart below shows, and have been labelled an “abject failure”.

The new target of ending peat sales by 2024 has also drawn criticism for being too slow. The CCC has previously recommended such a ban should come into force before 2023.

Other key measures with potential climate benefits include.

- Creating a new peatland map for 2024, which will improve land use decision-making and prevent trees being planted on peat sites – a major issue in the past.

- Developing guidance in the tree plan for when forested areas should be restored to peatland.

- Ensuring land managers implement wildfire management plans and exploring the embedding of these practices into agri-environment schemes, as fires can further deteriorate the quality of peatlands.

- Expanding and clarifying Countryside Stewardship incentives for farmers and land managers to look after and improve the environment.

-

Q&A: How will the UK’s strategies for trees and peat help achieve net-zero by 2050?

-

How will the UK government’s tree and peat strategies impact climate action?