Q&A: How the EU wants to race to net-zero with ‘Green Deal Industrial Plan’

Multiple Authors

03.17.23Multiple Authors

17.03.2023 | 3:12pmAt least 40% of the EU’s low-carbon technologies – from solar panels to heat pumps – will need to be made within its borders by 2030 under new plans.

The European Commission has set out a series of proposed targets and reforms that collectively make up its Green Deal Industrial Plan.

It is an explicit response to China’s dominance in the sector and the wave of low-carbon subsidies announced in the US Inflation Reduction Act last year.

In order to take on these rivals, the commission says EU member states need to cut “red tape”, end “excessive” bureaucracy and fast-track net-zero projects. It also calls for the bloc to ramp up production of “critical raw materials” for the low-carbon economy.

To help fund these activities, the commission has loosened rules around the money that governments can hand out to low-carbon companies – potentially paving the way for a subsidy race with other nations.

However, concerns remain over how member states and businesses will finance such a major industrial transition.

A reform of the EU’s electricity market design has also been released, which the commission says will help Europeans benefit from the expansion of cheap renewable power.

The commission has framed all of these proposals as a key part of its ambition to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief examines all of the proposals that together make up the EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan.

All of the proposals must now be discussed and agreed by the European Parliament and the EU Council before they can enter into force.

- Why has the EU produced a Green Deal Industrial Plan?

- What are the targets for low-carbon technologies in the EU?

- How would the EU cut ‘red tape’ for low-carbon projects?

- How does the EU plan to source ‘critical raw materials’?

- How is the EU proposing to reform electricity markets?

- How will EU green industry be financed and subsidised?

- How would the plan create ‘high-skilled jobs’?

- How does the plan aim to ensure ‘fair trade’ for ‘green’ businesses?

Why has the EU produced a Green Deal Industrial Plan?

Back in August 2022, US president Joe Biden made history by passing the largest package of domestic climate measures ever under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

The IRA contains $369bn for climate measures such as tax breaks for low-carbon energy and electric vehicles.

The bill initially attracted widespread praise, with many describing it as a landmark moment for climate action in the world’s second-highest emitting country.

However, by the autumn of 2022, tensions started to brew about how the IRA may affect industry and business in other countries – and even fuel a global “clean-energy arms race”.

Countries started to argue that the small print of the IRA – which stipulates that generous subsidies will only be on offer to companies operating mostly or wholly in the US – amounted to “green protectionism” and could harm business overseas.

There are two passages in the IRA that have particularly caused a stir.

The first is the stipulation that tax credits for low-carbon energy technologies, such as batteries, solar panels and wind turbines, should only apply to products made within the US. (This is shown in the extract of the IRA below.)

The second is a section of the act that offers US consumers tax credits to buy electric vehicles only if they’ve been assembled in North America. This passage also says that critical minerals and batteries needed for EVs must increasingly be bought from North America or a country with which the US has a preferential trade agreement.

At the forefront of criticism of these terms was the EU. On a trip to the US in December, French president Emmanuel Macron warned that the “protectionist” terms of the IRA risked “fragmenting the west”, according to the Financial Times.

Around the same time, European Commision president Ursula von der Leyen told an event that the IRA was “raising concerns” amid “a very particular backdrop for our industry and economy”, EurActiv reported.

As well as facing fears that the tax breaks laid out in the IRA could lure business away from Europe, the EU also has concerns about China’s tight grasp on the production of many minerals and technologies key for low-carbon energy.

China is currently the leading global supplier of low-carbon energy technologies. It holds at least 60% of the world’s manufacturing capacity for technologies such as solar, wind and batteries and accounts for 40% of electrolyser manufacturing, according to the International Energy Agency. It also has a near-monopoly on the production of many minerals critical for low-carbon technologies (more on this below).

On 17 January during the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos, von der Leyen told delegates that the EU would counter the IRA with its own Green Deal Industrial Plan, Reuters reported. She told reporters that she first had the idea for such a plan in September 2022, but did not yet have the support of all EU governments.

(It comes after the EU published its REPowerEU strategy in May 2022, which aimed to end the bloc’s reliance on Russian fossil fuels following the invasion of Ukraine. While this strategy focused on reducing fossil fuel use, the new Green Deal Industrial Plan focuses more on boosting low-carbon manufacturing and industry within Europe.)

On 1 February, the commission announced the first details of its Green Deal Industrial Plan. Von der Leyen said in a statement the plan would aim “to secure the EU’s industrial lead in the fast-growing net-zero technology sector”.

According to the commission, the plan can be split into four pillars.

The first pillar of the plan is to create a “simpler regulatory framework”.

To achieve this, the commission is proposing a new Net-Zero Industry Act to “identify goals for net-zero industrial capacity and provide a regulatory framework suited for its quick deployment”. (The Net-Zero Industry Act, which was published on 16 March, is discussed in more detail below.)

The commission added that the Net-Zero Industry Act will be complemented by a Critical Raw Materials Act to “ensure sufficient access to those materials”. (This act was also published on 16 March and is discussed in more detail below.)

The second pillar of the plan is to “speed up investment for clean-tech production in Europe”. To achieve this, the commision wants to amend its framework for state subsidies to increase support for low-carbon technologies. The commission also promised to facilitate the use of existing EU funds for low-carbon projects, it says.

The third pillar of the plan is to ensure the transition to net-zero creates new high-skilled jobs, according to the commission (more on this below).

And the final pillar of the plan is to ensure that any green trade is carried out “under the principles of fair competition and open trade”. (It comes after the EU accused the US of flouting World Trade Organization rules with the IRA, more detail below.)

All of the new legislation proposed by the commission will need to be approved by member state governments in the European Council and by public representatives in the European Parliament, before it can be implemented.

What are the targets for low-carbon technologies in the EU?

The proposed Net-Zero Industry Act repeats the EU’s commitment to reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 and, as a stepping stone, slashing emissions by 55% on 1990 levels by 2030.

Under a section titled “reasons for” the proposal, the commission cites recent plans to boost low-carbon industries in other countries, including the IRA and China’s green policies, as well as Japan’s Green Transformation programme and India’s Production Linked Incentive scheme. (A leaked draft of the act said these schemes risked “dragging away” investments from the EU).

The proposed act sets a “headline benchmark” of ensuring that at least 40% of low-carbon technology needs are met by manufacturing within the EU by 2030.

Specifically, this target applies to a list of eight “strategic net-zero technologies”, which excludes nuclear power. The eight technologies are:

- Solar power and solar thermal

- Onshore and offshore wind power

- Batteries and energy storage

- Heat pumps and geothermal energy

- Electrolysers and fuel cells

- Sustainable biogas/biomethane

- Carbon capture and storage (CCS)

- Grid technologies

The proposal says the 40% benchmark represents “an overall political ambition of achieving high resilience across strategic net-zero technologies and the overall energy system, while taking into account the need to pursue that ambition in a flexible and diversified way”.

It notes that for some technologies, such as solar PV modules, the 40% figure “represents a realistic, but ambitious scale-up effort of the corresponding manufacturing capacity”. (Europe currently imports nearly all of its solar PV modules – mostly from China, according to the International Energy Agency.)

An earlier leaked version of the act had listed specific manufacturing targets for different low-carbon technologies by 2030, but they did not make it into the final draft. These included:

- Ensuring 40% of solar annual deployment needs are met by manufacturing in the EU.

- Ensuring 85% of wind annual deployment needs are met by manufacturing in the EU.

- Ensuring 60% of heat pump annual deployment needs are met by manufacturing in the EU.

- Ensuring 85% of battery annual demand is met by manufacturing in the EU.

- Ensuring 50% of the renewable and green hydrogen annual deployment needs are met by electrolyser manufacturing in the EU.

These initial targets “raised a lot of eyebrows”, says Domien Vangenechten, a senior policy adviser at climate thinktank E3G. He tells Carbon Brief:

“They were very technology specific. I think the EU is taking the safe route here by saying we’re not going to be very prescriptive by setting manufacturing targets for individual sectors, but more healthy aspirational targets.”

He added that it is likely that the 40% benchmark figure will be further digested and scrutinised in the coming months.

Achieving the benchmark would require shifts to global low-carbon energy supply chains.

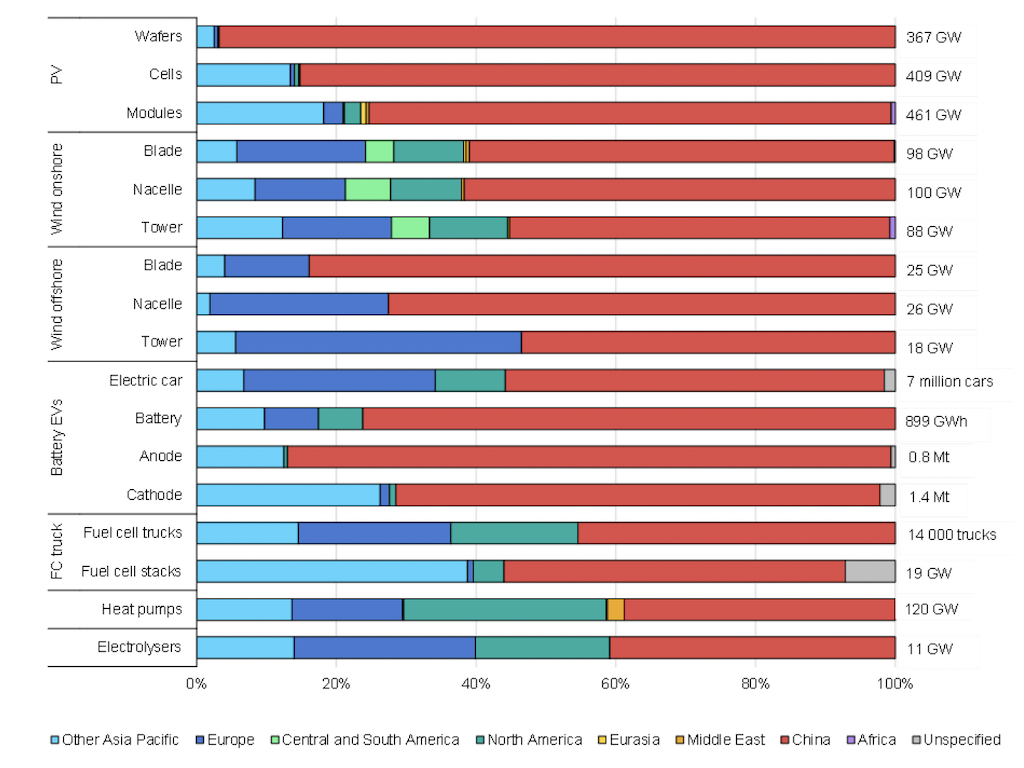

China is currently the leading global supplier of low-carbon energy technologies. It holds at least 60% of the world’s manufacturing capacity for technologies such as solar, wind and batteries and accounts for 40% of electrolyser manufacturing, according to the International Energy Agency.

The chart below, also from the IEA, shows China’s dominance (red) in manufacturing capacity for low-carbon technologies such as solar, wind and batteries in 2021.

Another target, which is quite distinct from the rest of the strategy, is an EU-wide objective to develop 50m tonnes of CO2 storage by 2030. There is currently no “injection capacity” in the EU, but countries such as Denmark and Netherland are already working on plans.

The commission plans to mandate existing oil-and-gas producers to make depleted gas fields and other capacity available to store CO2.

Simone Tagliapietra, from the thinktank Bruegel, tells Carbon Brief that, in his view, this is “the most viable element” of the whole Net-Zero Industry Act, as it would see an EU-wide target broken down into individual targets for fossil fuel companies.

How would the EU cut ‘red tape’ for low-carbon projects?

The Net Zero Industry Act’s primary aim is to create a “predictable and simplified regulatory environment” for net-zero projects. In her statement introducing the the Green Deal Industrial Plan, Von der Leyen said:

“It will speed up permitting – this is one of the major complaints. When you speak to the net-zero industry, the major complaint is always the permitting processes…A big focus is on cutting red tape.”

This point is reiterated in the act, which says:

“The unpredictability, complexity and at times, excessive length of national permit-granting processes undermines the investment security needed for the effective development of net-zero technologies manufacturing projects.”

The issue of long permitting delays for building new EU wind and solar projects was addressed in the REPowerEU plan last year. The European Parliament subsequently agreed on a tightened nine-month permitting time for installations in designated “renewable acceleration areas”, though this still needs to be approved by member states.

Rather than installation, this week’s new act focuses on factories for manufacturing these low-carbon technologies and their components.

As it stands, such facilities take between two and seven years to undergo permitting, the commission says, depending on the country and technology.

The commission proposes to dramatically shorten this time, but how much depends on whether or not technologies are deemed “strategic”.

Eight “strategic net-zero technologies” – the ones covered by the 40% manufacturing target – are given “priority status”. They have been selected on the basis of being “commercially available”, with “a good potential for rapid scale-up”.

The commission says new factories for strategic net-zero technologies should be given a permit within 12 months, if they have annual manufacturing capacity of more than 1 gigawatt (GW). This falls to nine months if their output is below 1GW.

If member state authorities fail to comply with these time limits, projects would be automatically approved, unless they require a specific environmental impact assessment.

Factories making other net-zero technologies are also covered by the act, but they have longer permitting time limits of 18 months and 12 months, for sites with output above and below 1GW, respectively. (For projects that are not measured on a GW basis, the upper time limits would apply.)

Technologies that are not included on the priority list include sustainable aviation fuels and, significantly, nuclear power.

The latter was initially pegged to appear as the ninth “strategic” technology on the priority list. However, there were reports of disputes between commissioners over whether it should stay.

In the end, the act only covers factories making machinery and components for “advanced” nuclear technologies and “small modular reactors”, rather than for nuclear power plants in general.

Under the commission’s proposals, member states would set up a national authority as a “one stop shop” for permitting net-zero manufacturing projects. While it says EU environmental assessments are “an integral part” of permit granting, it also states:

“Based on its case-by-case assessment, a responsible permitting authority may conclude that the public interest served by the project overrides the public interests related to nature and environmental protection and that consequently the project may be authorised.”

Some environmental NGOs have expressed concern about deregulation and looser permitting processes that might clash with environmental protections. European Commission climate lead Frans Timmermans acknowledged these concerns in a press briefing launching the act, explaining:

“It sounds like squaring the circle when you first start thinking about this, but what we think we can do is speed up processes without undermining our nature legislation, and I think this can be done through streamlining the processes [and] working very closely with authorities at all levels to also employ industry from the get-go.”

Timmermans also seemed optimistic about public support for the strategy. He cited the broad support for moving away from Russian fossil fuels following the invasion of Ukraine, adding that “the whole issue of NIMBY [not in my back yard] has become completely different”.

How does the EU plan to source ‘critical raw materials’?

“Critical raw materials” are defined by the EU as metals and minerals that are economically important, but have high risks associated with their supply.

Many are vital for the net-zero transition, including the lithium used in batteries and the copper for wind turbines. The International Energy Agency (IEA) anticipates that global demand for these kinds of materials will roughly quadruple over the next two decades.

EU officials have often made the comparison with the bloc’s current dependence on fossil fuel imports from foreign powers. Von der Leyen said in her 2022 state of the union address that “we must avoid becoming dependent again, as we did with oil and gas”.

The EU is 100% dependent on imports for half of the 30 minerals it defined as “critical”, as of 2020, according to research institute DIW Berlin. The institute also notes that many of the countries the bloc is dependent on are “less democratic”.

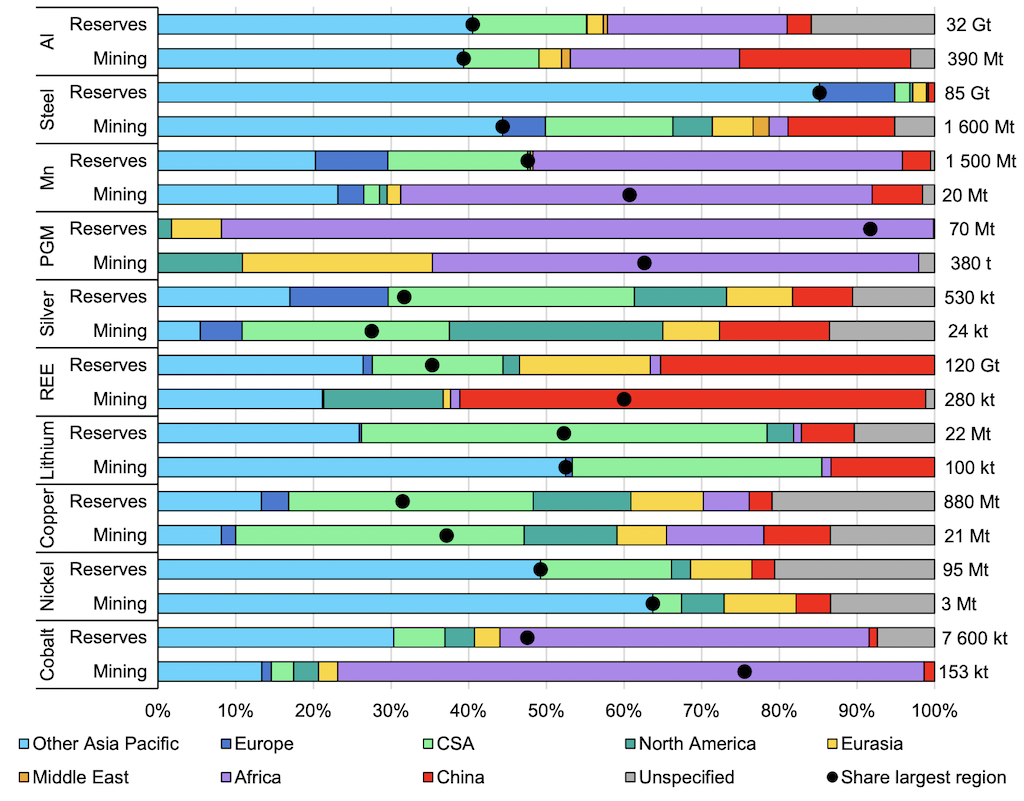

Europe does not have a large share of many critical mineral reserves, nor does it account for much mining. This can be seen in the IEA chart below, with the continent’s shares for key resources indicated by dark blue bars.

China is seen as the main focus of this part of the EU’s plan. China has a near-monopoly on many critical mineral exports, which has already led to supply chain issues in Europe.

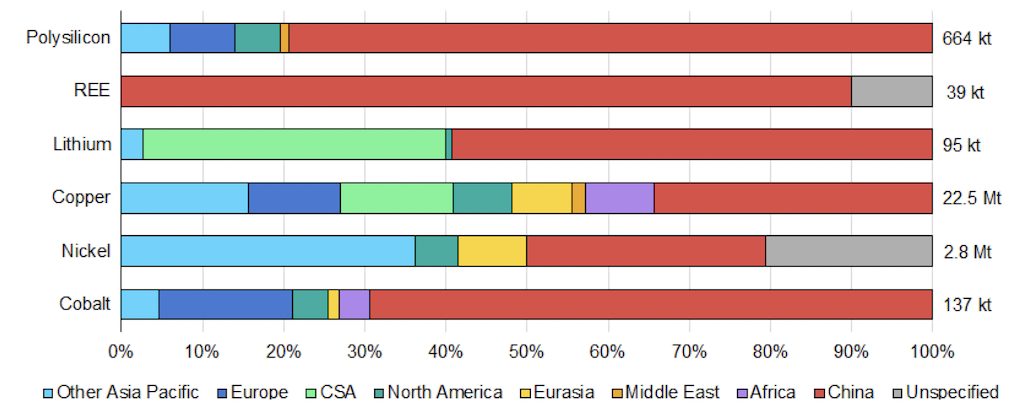

This is generally not because of China’s large reserves – as seen in the figure above – although it does mine more rare-earth elements than any other country. Instead, as the IEA chart below shows, China (red) tends to dominate in the processing and refining of minerals.

The Critical Raw Materials Act, another component of the EU’s strategy, includes goals of increasing the bloc’s domestic capacity, diversifying its trading partners, monitoring for future risks and increasing the “circularity and sustainability” of critical raw material use. It states:

“The risk of supply disruptions is increasing against the background of rising geopolitical tensions and resource competition.”

Industries such as lithium and rare-earth metal mining are essentially non-existent in the EU, although it does have some reserves. The commission proposes scaling up rapidly by giving special treatment to “strategic projects” involved with mining, processing or recycling.

These projects would be identified by the commission, working with a European Critical Raw Materials Board – a new central purchasing agency to coordinate action across the EU.

The act adds that the recently revised state aid rules may allow countries to channel more public funds into critical minerals extraction. (See: How will low-carbon technologies be financed under the Green Deal Industrial Plan?)

As it stands, permitting for mines in the EU can take a decade or more. The act emphasises the need to speed up the early stages of strategic projects, noting that assessment processes “should remain light and not overly burdensome”.

Campaigners have expressed concerns that this would mean environmental safeguards are overlooked and communities are ignored. The development of new mines in some parts of the bloc is already facing a backlash, for example from Portuguese villagers and Indigenous groups in Sweden.

The act acknowledges these issues, emphasising the importance of “ensuring environmental protection, socially responsible practices and transparent business practices”. It adds:

“As public acceptance of mining projects is crucial for their effective implementation, the promoter should also provide a plan containing measures to facilitate public acceptance.”

One way to reduce the need for new mines is to lean more into recycling. Prof Lukas Menkhoff, head of the global economy department at the thinktank DIW Berlin, tells Carbon Brief he is “glad to see a quota for recycling” in the act, but adds:

“In the short-run, however, 15% may be ambitious, if we think, for example, about batteries from cars which may not be often replaced until 2030.”

The EU does not have sufficient reserves of every critical raw material within its borders. The act, therefore, acknowledges the need to rely on other nations for imports, but emphasises diversifying the bloc’s supply chains.

The commission lays out the need for partnerships with trusted, resource-rich countries where it can support “strategic projects” that will guarantee the EU a supply while remaining “mutually beneficial”. It mentions Chile and Australia as having potential for “win-win partnerships”.

These projects could be supported by the EU’s Global Gateway, a €300bn pot for financing EU interests abroad. The commission emphasises that “high environmental and social conditions continue to apply” for these foreign initiatives.

The act sets a target of not being dependent on one single nation outside of the EU for more than 65% of any one critical raw material by 2030. This proposal has reportedly already made waves in China’s renewables industry.

Diego Marin, a policy officer for raw materials at the European Environmental Bureau (EEB) tells Carbon Brief that Chile, for example, already provides more than 65% of the EU’s lithium, but says this is unlikely to be wound back:

“Chile and the EU have a pretty good relationship. I think this is more of a dig at China.”

The Green Deal Industrial Plan also mentions “explor[ing] the creation of a Critical Raw Materials Club” to bring together consumer and producer countries. (On 13 March, the Financial Times reported that the US and EU have launched new talks on critical minerals.)

How is the EU proposing to reform electricity markets?

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused energy prices to spike last year, the European Commission pledged to reform the EU’s electricity market rules.

In doing so, the commission hoped to make energy bills less susceptible to swings in fossil fuel prices, of the kind seen when Russian gas supplies were curtailed. It also wanted to allow consumers to experience the benefits of lost-cost renewable power.

Under the existing system, electricity prices are set in the same way as for all other commodities, via “marginal pricing”. In practice, this means electricity prices are set by the most expensive power plant needed to meet demand at each moment – usually gas – rather than by increasingly cheap renewables.

In response to the high cost of electricity driven by record-high gas prices, the commission expressed a desire to “decouple” electricity from gas prices.

However, EU member states have disagreed about how ambitious these market reforms should be. Nations including France and Spain have favoured extensive changes, while Germany among others has warned against such deep reforms.

The commission has now published its proposals for reform as part of the bundle of Green Deal Industrial Plan documents.

In the end, it has opted for a system that would support the deployment of renewables, but would not fundamentally change the way the electricity market is structured. It argues that this will, ultimately, yield the same result of reducing reliance on fossil fuels and cutting bills.

“The commission plans to tackle high prices from gas power generation in the best way – by reducing its significance,” said Vilislava Ivanova, clean energy systems research manager at E3G, in a statement.

However, the commission acknowledges that until renewable power has become even more widespread, “we need to structure consumer contracts in a way that reduces their volatility, and decouples citizens’ energy bills from the prices in short-term wholesale markets”.

Therefore, it proposes giving consumers a wider choice of energy contracts and the option to lock in long-term prices. “This will, in practice, reduce their exposure to any price surge,” it explains.

It says that people should still be able to choose flexible power contracts for items such as electric cars, to benefit from periods of low electricity prices by charging overnight, for example.

Long-term electricity contracts would also be available for large consumers in industry, through power purchase agreements (PPAs), which would guarantee more stable prices.

Low-carbon power developers would also benefit from greater stability under the commission’s plans, in the form of contracts for difference (CfDs).

The reforms would require any new public financial support for renewables and nuclear power to be in the form of CfDs. Such contracts provide guaranteed revenue to project developers, while member states would be obliged to give back any excess revenue they make from the projects to consumers.

The UK government has effectively deployed CfDs to scale up its renewable capacity, but they are not currently widely used across the EU.

Summarising its proposals, the commission states:

“The ultimate objective is to provide secure, stable investment conditions for renewable and low-carbon energy developers by bringing down risk and capital costs while avoiding windfall profits in periods of high prices.”

How will EU green industry be financed and subsidised?

A key goal of the Green Deal Industrial Plan is to “speed up investment and financing for clean tech production in Europe”.

The Net Zero Industry Act makes several proposals. These include establishing a Net Zero Industry Platform to “identify bottlenecks and potential best practices” for finance.

However, perhaps the most significant financial element of the plan has already been implemented. Following a brief consultation with member states, the European Commission has loosened state aid rules for renewables and other low-carbon projects.

This could herald a “subsidy race” as member state governments now have more leeway to pump billions of euros into low-carbon technologies to match the US and other nations.

The move has variously been described as a “radical departure” and a “paradigm shift” for the EU. The bloc has traditionally put tight boundaries on national subsidies, to prevent member states from entering into subsidy races with each other.

As of 9 March, however, the Temporary Crisis Framework, which was initially set up as a short-term measure to help member states following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, has been renamed the Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework.

This framework allows member states to spend money on “measures needed for the transition towards a net-zero industry” until the end of 2025. However, they will only be allowed to “match” subsidies seen outside the EU, in order to prevent industries leaving the bloc.

Accompanying this is a revision of the General Block Exemption Regulation, through which the commission can approve certain categories of state aid. This revision adds key low-carbon sectors, such as hydrogen and zero-emission vehicles, to the list of industries eligible for subsidies. This will allow member states to provide state aid to these sectors without notifying the commission.

The new rules have proved controversial.

Smaller EU nations raised concerns about harmful competition within the bloc, fearing they could be outgunned by larger and wealthier member states. EU competition chief Margrethe Vestager acknowledged that “European countries are not equal when it comes to state aid”.

In the past, subsidy packages have been dominated by the bloc’s larger economies. For example, Germany and France accounted for around 80% of the state aid under the first iteration of the Temporary Crisis Framework. Both countries have been enthusiastic about relaxing state aid rules in response to the US Inflation Reduction Act.

Environmental NGOs voiced these concerns about competition within the EU in a joint letter to the commission:

“The mere relaxation of state aid rules without substantial additional environmental safeguards and financial mechanisms is likely to lead to further divergence across EU economies, as poorer EU countries may not have the fiscal space for investing in the green transition.”

The commission has tried to address some of these concerns – for example, by imposing some restrictions on applications for subsidies in larger EU states.

Olivier Vardakoulias, a finance and subsidies policy expert at Climate Action Network Europe, tells Carbon Brief that NGOs are also concerned about the focus of the EU proposals on public subsidy, without equivalent consideration for regulating or directing private funds:

“If one provides carrots to EU industry in the form of public subsidies, what are the sticks? Especially for big companies that clearly have access to private finance. There is a question mark there around whether this is the best use of public resources at a time of a cost of living crisis and huge investment needs for green public infrastructure to meet climate, biodiversity and circular economy targets.”

Aside from relying on member states to introduce subsidies, the plan mentions “facilitating” the use of existing EU funds, such as those from REPowerEU and InvestEU.

Beyond this, NGOs have called for completely new EU funding sources. The commission is working on a proposal to do this, namely a “European Sovereignty Fund”.

This will be discussed during the revision of the EU’s multiannual budget this summer and is meant to provide a “structural answer to the investment needs” of the bloc. It is unclear how much money this would entail and where it would come from.

Following the launch of the Net-Zero Industry Act, the Financial Times reported on warnings from low-carbon business leaders that the plans “will fail unless they are backed up with more money”. It also noted concerns that the act’s emphasis on using EU-sourced technologies could result in higher prices and lower quality for low-carbon products.

How would the plan create ‘high-skilled jobs’?

The third pillar of the commission’s proposed Green Deal Industrial Plan is to create “well-paid quality jobs” in the low-carbon technology sector.

This is important because an estimated 35-40% of all jobs in the EU could be “affected” by the transition to net-zero, the commision said in a statement.

The Net-Zero Industry Act proposal says that the commission will provide seed funding to support the establishment of “net-zero industry academies”.

The aim of these academies will be to develop training and education on how to produce low-carbon technologies and to enhance the skills of the existing workforce in member states, according to the act.

It states that EU member states should assess the efficacy of the learning programmes developed by the net-zero industry academies by the end of 2024 and every two years after.

The academies should be overseen by a “net-zero Europe platform”, the act says.

This platform should also “facilitate closer coordination and the exchange of best practices between member states to enhance the availability of skills in the net-zero industry, including by contributing to Union and member states policies to attract new talents, both from the Union and from third countries”.

How does the plan aim to ensure ‘fair trade’ for ‘green’ businesses?

The fourth pillar of the Green Deal Industrial Plan is to ensure that any “green trade” is carried out “under the principles of fair competition and open trade”.

It comes after the EU accused the US of flouting World Trade Organization rules with the IRA. (China recently accused the EU of flouting WTO standards with its carbon border adjustment mechanism.)

To this aim, the commission will continue to “develop the EU’s network of free trade agreements” to support its net-zero goal, it says.

An earlier leaked draft of the Net-Zero Industry Act had some experts concerned that the EU itself may be acting in a protectionist manner with some of its proposed terms.

As EurActiv noted in its reporting, the leak stated that, for public procurement, EU authorities should consider the “tender’s contribution to the security of supply”.

It further added that security of supply depends on “the proportion of the products originating in third countries”.

This could have been interpreted as meaning that authorities will have to consider whether the low-carbon technology they are buying is produced within the EU or not. Such a stipulation could have put the proposal in conflict with the WTO’s Government Procurement Agreement, an expert told EurActiv.

However, the final version of the proposal revised the language around public procurement. It instead says that EU authorities should take into account “the proportion of the products originating from a single source of supply” rather than from “third countries”.

This can be interpreted as a “positive change” in terms of open trade, says Ignacio Arroniz, a trade and climate researcher at E3G. He tells Carbon Brief:

“It’s the difference between saying that you should not depend on any country [outside of the EU] to that you should not depend on one given country…It’s got more of an anti-China feeling to it, but it doesn’t have an ‘anti-every other country’ feel.”

(China currently supplies almost all of Europe’s solar PV module imports, as well as around half its battery and EV imports, according to the IEA.)

Experts tell Carbon Brief that, overall, the commission’s proposal is framed more around competition with other nations than explicitly boosting climate action.

Avantika Goswami, programme manager for climate change at Indian thinktank CSE, tells Carbon Brief that an industrial decarbonisation strategy from the EU is welcome:

“With more investment in green industry by the EU, over time those technologies could be deployed more and then over time costs could go down, and that could be made available to the rest of the world…[But] there are a lot of ‘what ifs’ involved in that.”

However, she also voices concerns about the impact potentially punitive trade policies could have on industries in global south nations, as they attempt to decarbonise.

-

Q&A: How the EU wants to race to net-zero with ‘Green Deal Industrial Plan’