Q&A: How the ‘climate assembly’ says the UK should reach net-zero

Multiple Authors

09.10.20Multiple Authors

10.09.2020 | 12:01amIn January 2020, more than 100 randomly selected members of the public met in a secret location in Birmingham to begin taking part in the UK’s first “climate assembly”.

Lasting five months, the assembly asked citizens to listen to advice from climate experts before coming up with a list of recommendations for how the country should reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

The assembly’s final report, published today, recommends changes across a broad range of sectors, from meat-and-dairy consumption and air travel through to zero-carbon heating and electricity generation.

Measures receiving high levels of support from the assembly include: a levy for frequent fliers; a ban on the sale of petrol, diesel and hybrid cars by 2030-35; and a switch to a more biodiversity-focused farming system.

However, some measures for stronger climate action did not receive strong support. For example, the assembly did not recommend reaching net-zero emissions earlier than 2050.

In this in-depth Q&A, Carbon Brief walks through the assembly’s recommendations for every sector of the UK’s economy.

- What is the UK Climate Assembly?

- What is the point of citizens’ assemblies?

- What does the assembly recommend?

- Land transport

- Air travel

- Homes

- Food, farming and land use

- Consumption of goods and services

- Electricity

- Greenhouse gas removal

- Green recovery

- Net-zero date and additional proposals

- What happens next?

What is the UK Climate Assembly?

The Climate Assembly is a randomly selected and representative group of 108 UK citizens, aged 16-79, tasked with working out how the country should reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

The membership of the assembly was drawn from a larger group that responded to a recruitment letter, four-fifths of which were sent to random UK addresses inviting adults in the household to take part. One fifth of the recruitment letters were reserved for the UK’s most deprived areas.

The final membership was selected to be representative of the UK in terms of age, gender, ethnicity, education, rural versus urban, geography and level of concern about climate change.

Members met across six weekends in the first half of this year to hear “balanced, accurate and comprehensive information” relevant to their task, from 47 speakers. This was followed by facilitated discussions, before the assembly agreed on a set of recommendations decided by vote.

[The assembly moved online after its first three meetings as a result of the coronavirus lockdown.]

The assembly was assisted by four “expert leads”, who worked with the organisers to come up with themes and the focus for each panel of speakers. These leads were: Chris Stark, chief executive of the Committee on Climate Change; Prof Jim Watson, University College London; Prof Lorraine Whitmarsh, University of Bath; and Prof Rebecca Willis, University of Lancaster.

The final membership was selected to be representative of the UK in terms of age, gender, ethnicity, education, rural versus urban, geography and level of concern about climate change. Credit: Fabio De Paola / PA.

The assembly was set up on the initiative of six parliamentary committees, shortly after the then prime minister Theresa May committed the UK to its new, more ambitious climate goal, in June 2019. A press release announcing the assembly explained:

“The Citizens’ Assembly is designed to explore views on the fair sharing of potential costs of different policy choices and is intended to provide input to future select committee activity and will inform political debate and government policy making.”

The process was funded by the House of Commons and two philanthropic organisations, the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the European Climate Foundation (ECF), which “did not have a say in how the assembly was run or what it covered”. [ECF also funds Carbon Brief.]

Today’s 556-page report is the culmination of the assembly’s work. It sets out the way the assembly was established, its mode of work and its recommendations for reaching net-zero.

Its recommendations for each area were chosen and prioritised in a series of secret votes. For each proposal, the report also shows the level of support it received from assembly members.

Crucially, however, the recommendations are accompanied by a detailed rationale from the assembly, setting out the advantages and disadvantages they considered.

What is the point of citizens’ assemblies?

Citizens’ assemblies are an example of what is variously called “deliberative”, “participatory” or “consultative” democracy. According to the final report of the UK assembly, such groups are increasingly being used around the world:

“[A]ssemblies enable decision-makers to understand people’s informed and considered preferences on issues that are complex, controversial, moral or constitutional.”

The UK parliament convened a citizens’ assembly on the future of social care in 2018 and other countries have recently organised similar groups.

The conclusions of an Irish citizens’ assembly helped to overturn the country’s abortion ban. The assembly then moved on to the question of climate change, publishing its findings in 2018.

France has also convened a climate assembly, named the “Convention Citoyenne pour le Climat”. This delivered recommendations on how the country should cut emissions to 40% below 1990 levels by 2030 “in a spirit of social justice”.

French president Emmanuel Macron went on to say that he was accepting all but three of the assembly’s 149 recommendations, according to press reports at the time.

Some argue the French assembly was a response to the “gilets jaunes” (yellow vests) protests which began in 2018, with the Economist saying “President Emmanuel Macron devised it in an attempt to calm the country”. The weekly magazine says the assembly was asked “how to make green policy palatable, efficient and fair”.

A citizens’ assembly was one of three “demands” made by protest group Extinction Rebellion (XR). The group also called for the government to be “led by the decisions” that the assembly made.

According to an ECF blog on the concept of assemblies, XR has argued that “a citizens’ assembly could transcend the politics-as-usual that hold back effective policy”. The protest group says:

“[B]ecause they are informed and democratic, the Citizens’ Assembly’s decisions will provide political cover and public pressure for politicians to set aside the usual politicking and do the right thing.”

Some commentators have questioned the whole concept of citizens’ assemblies, arguing that they are not truly representative. The Spectator’s Melanie McDonagh says they are “a brilliant way for elected politicians to shift the responsibility for really unpopular policies onto someone else”, but that the members “don’t, unlike elected politicians, actually have to deal with the consequences of their breezy and idealistic proposals”.

“Ultimately, the impact of citizens’ deliberation depends on the link to decision-making,” writes Mathilde Bouyé, associate at the World Resources Institute, in a piece at Carnegie Europe that gathers a variety of views on the usefulness of the concept.

A key distinguishing feature of the French assembly is that its recommendations were, at least in theory, binding and tied directly to the decision-making process. Therefore, unlike most such assemblies, it was given “real power”, according to Involve, the charity that facilitated the UK process.

As a feature in Wired magazine notes, it “remains to be seen if the suggestions [of the UK assembly] will be taken onboard”.

What does the assembly recommend?

The report includes more than 50 key recommendations for policies that could help the UK meet the net-zero target by 2050, as well as suggestions for the nation’s recovery from Covid-19.

Besides sector-specific policies, there are also a number of key themes that Sarah Allan, head of engagement at Involve, described in a press briefing as “running through those recommendations a bit like messages in a stick of rock”.

In the first weekend the assembly met, members decided on 25 “underpinning principles” for the path to net-zero.

Everyone voted on the proposed principles, with votes indicating which ones they considered to be “priorities” rather than merely which ones they supported.

The most important principles to emerge were “informing and educating everyone”, with 74 votes, ensuring fairness for everyone, with 65 votes, and leadership from the government that is “clear, proactive, accountable and consistent”, with 63 votes.

Other important principles identified included restoring the natural world, local community engagement and, simply, “urgency”.

Chris Stark, chief executive of the Committee on Climate Change, explained the significance of these ideas to a press briefing:

“These principles themselves are recommendations to government – and to parliament, for that matter – so they are important. Secondly, though, they were used by the assembly members themselves on the work that they did.”

Besides leadership from the current government, the assembly also indicated a desire for cross-party consensus on how to get there. “[There was] recognition that this is something that is going to go through decades and changes of government,” said Stark.

Sir David Attenborough and Chris Stark address the Climate Assembly. Credit: Fabio De Paola / PA.

Land transport

The report considers “land transport” to include any forms of transit over the land surface, including private vehicles, freight, public transport and “active” forms, such as walking and cycling.

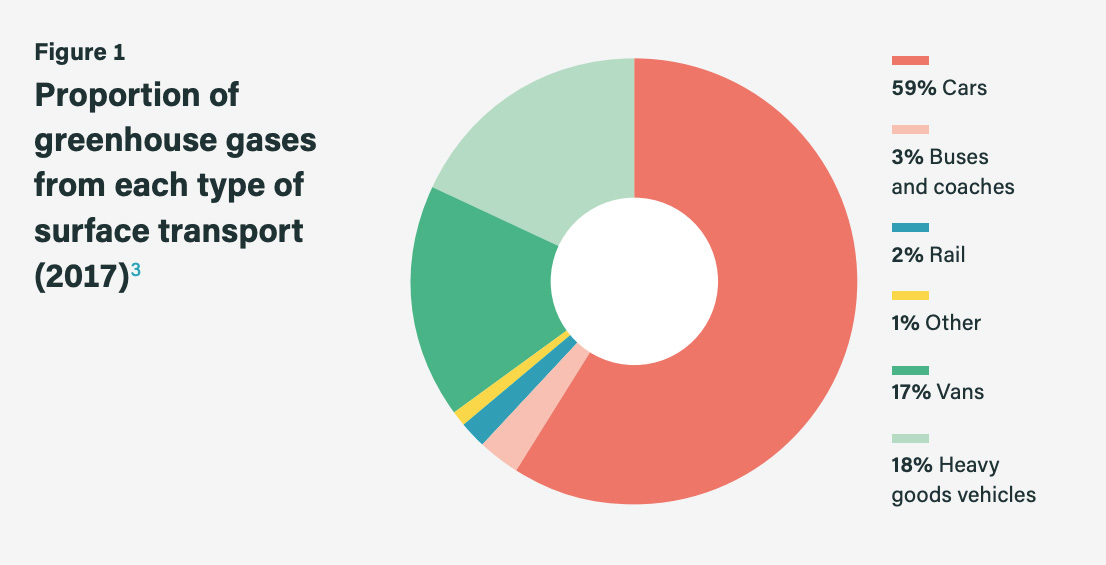

Taken together, land transport accounts for 70% of the UK’s transport greenhouse gas emissions and 23% of the UK’s total emissions. The report notes – and the chart below highlights – that “most of these emissions come from cars, with just 5% arising from public transport”.

Proportion of UK greenhouse gas emissions from each type of surface transport (in 2017). Credit: Climate Assembly UK (2020), based on data from the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. Credit: Climate Assembly UK (2020).

However, due to time constraints, the Climate Assembly agreed to focus on “personal transport”, which includes travel for work, pleasure and everyday activities. This accounts for 15% of the UK’s total emissions, the report says.

Of the assembly members, 36 were randomly selected from a stratified sample to consider the topic of surface transport in-depth. This approach ensured that the group “remained reflective of the wider UK population in terms of both demographics and their level of concern about climate change”, the report explains.

The group first formulated and agreed a set of key considerations that the government should bear in mind for land transport. Of the 18 they produced, the five with the highest priority are shown below (the brackets show the percentage of assembly members that chose that consideration as a priority):

- Ensure solutions are accessible and affordable to all sections of society (56%)

- Help create significant change at an individual level, including through education, incentives and disincentives (47%)

- Achieve cross-party support for decisions so that they are not changed by successive governments (39%)

- Follow the principle that the polluter should pay (36%)

- Check and be careful about side effects, including moral, ethical and environmental implications (33%)

Next, after exploring and voting on a range of possible futures for UK surface transport, the assembly suggested a future involving (in its own words):

- A ban on the sale of new petrol, diesel and hybrid cars by 2030-35

- A reduction in the amount we use cars by an average of 2-5% per decade

- Improvements to public transport

The report notes: “The idea of better public transport was overwhelmingly mentioned as a positive in assembly members’ discussions. Some assembly members also welcomed the idea of improvements to the infrastructure for active transport.”

Looking at a range of possible policies, a majority of assembly members backed 15 options in total, under the three categories (brackets show percentage of members that agree or strongly agree with the policy compared with those that disagree or strongly disagree):

1.Moving quickly to low-carbon vehicles:

- Government investment in low carbon buses and trains (91%/6%)

- Quickly stop selling the most polluting vehicles (86%/11%)

- Grants for businesses and people to buy low-carbon cars (74%/9%)

- Car scrappage scheme (66%/9%)

- Advertising restrictions on the most polluting cars (58%/15%)

2.Discouraging car ownership and use:

- Localisation (72%/20%)

- Car clubs (59%/11%)

- Charging to use the roads (56%/39%)

- Closing roads to cars (53%/23%)

3.Increasing the use of public and active transport

- Adding new bus routes and more frequent services (86%/9%)

- Making public transport cheaper (83%/14%)

- Bringing public transport back under government control (75%/11%)

- Investing in cycling and scootering facilities (70%/9%)

- Increasing investment to make buses faster and more reliable (66%/9%)

In general, assembly members were “more supportive of policies to improve public – as opposed to active – transport”, the report notes. Overall, the most-supported policy options were government investment in low-carbon public transport, quickly stopping selling the most polluting vehicles, and adding new bus routes and more frequent services, the report says.

Among the policies not backed by members were access to longer range cars for electric car owners, lowering speed limits on dual carriageways or motorways, and grants for electric bikes.

Air travel

Air travel accounts for 22% of the UK’s total greenhouse gas emissions from transport, the report says, and 7% of the UK’s emissions overall. It adds that “emissions from flying have grown significantly in the last 30 years”.

The report notes that air travel’s contribution to the UK’s emissions includes both domestic and international travel. However, the latter only includes travel that starts in the UK and ends in another country – it does not include incoming flights or internal flights made by UK travellers when abroad. International flights account for 96% of the UK’s air travel emissions.

As with land transport, the Climate Assembly only considered “personal” transport, which includes travelling for work and pleasure, but not freight.

Thirty-six assembly members were selected to consider the topic in more detail. Again, as in the land-transport group, they first produced and voted on a set of considerations for the government to take into account on air travel.

Those voted as the highest priority include: speeding up progress on technology, such as electric planes and synthetic fuels (chosen by 53% of members); influencing the rest of the world, particularly the US and China (50%); and evening out the cost of air travel versus alternative forms of transport by making the latter cheaper and better (50%).

After deciding on the most important considerations, the assembly members looked into the future of UK air travel. The “expert leads” on the topic presented five scenarios of possible futures. From their votes and deliberations, the assembly members expressed a preference for a future where:

- Air passenger numbers increase by 25-50% between 2018 and 2050, depending on how quickly technology progresses.

- 30m tonnes of CO2 is still emitted by the aviation sector in 2050 and requires removing from the atmosphere.

Comments during the discussions suggest that the members favoured “a solution to air travel emissions that allows people to continue to fly”, the report notes:

“They cited rationale including freedom and happiness for this preference, as well as – to a slightly lesser extent – benefits to business and the economy. Some assembly members expressed scepticism about the feasibility of significant changes to passenger numbers.”

And speaking at a press conference ahead of the report’s publication, Prof Jim Watson – professor of energy policy at University College London and one of the Climate Assembly expert leads – noted that a 25-50% growth in passenger numbers would be “a lower rate of increase than we have seen in the last two to three decades – so it’s growth, but it’s much slower growth”. He added:

“It’s lower growth than the industry has put forward for that period – and the high end of that is the central projection for the Department for Transport.”

As a result, the group looked at policy options around managing the amount people fly and ensuring investment in greenhouse gas removals.

Overall, assembly members “were generally supportive of policies to manage the amount we fly, ensure investment in greenhouse gas removals and invest in the development and use of new technologies for air travel”, the report says.

However, there were “strong and clear preferences” within these policy options, it adds.

For example, members preferred managing flying demand through carbon taxes “that increase as we fly more often and as we fly further” – supported by 80% of members – rather than a blanket tax on all flights. There were concerns on the latter around fairness – particularly that it would have a disproportionate impact on people with lower incomes.

In terms of investment in greenhouse gas removals, assembly members tended to favour investment from the airline industry, the report says – with 75% agreeing or strongly agreeing that this should be part of how the UK gets to net-zero. There was also “significant, albeit slightly lesser, support” for the idea of investment from a wide range of organisations, the report adds, and less enthusiasm for direct government investment.

Discussions at the Climate Assembly. Credit: Fabio De Paola / PA.

A general feeling behind these preferences was that “the polluter should pay”, the report says:

“Some also felt airline industry investment would incentivise quicker process on new technologies. There was, however, uneasiness amongst some assembly members, too…they suggested a need to monitor, scrutinise and perhaps enforce airline industry investment to ensure it actually took place.”

Finally, the group expressed strong support – backed by 87% of members – for the development and use of new technologies in air travel. There was a “wish to see technology develop quickly, and support for a technology-based solution to air travel emissions in general”, the report says, although “some assembly members raised concerns or conditions, including a wish not to rely solely on hopes of technological progress”.

Homes

In the strand addressing housing, which is responsible for 15% of the UK’s emissions, 35 assembly members were selected to consider two key topics: retrofitting and zero-carbon heating.

They spent weekend three of the assembly discussing the evidence they had heard and establishing what needed to be taken into consideration, as well as what needed to happen in terms of policy changes to improve heating and energy use in homes.

Of the 23 considerations identified, the five with the highest priority were (the brackets show the percentage of assembly members that chose that consideration as a priority):

- Any strategy needs to be enforceable by government and binding for future governments (60%)

- It needs to “work for everyone”, no matter their housing type or location (54%)

- Education and good communication on the topic (51%)

- “Imaginative solutions/incentives” to make work financially viable (46%)

- Learn from others and avoid making expensive mistakes (43%)

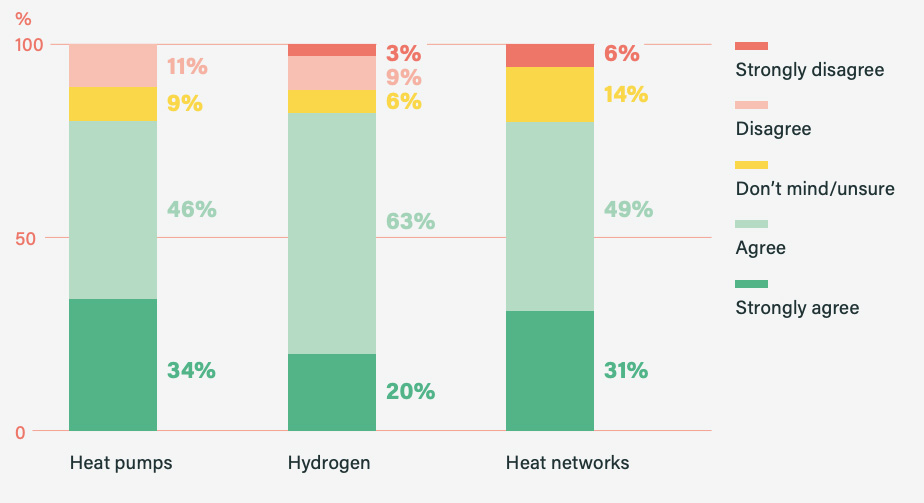

Overall, the assembly showed strong support for hydrogen, heat pumps and heat networks as part of the solution to decarbonising homes, as the chart below indicates.

Assembly members’ views on whether different zero-carbon heating options should be part of the UK’s strategy to reach net-zero. Credit: Climate Assembly UK (2020).

There was also a strong consensus (94%) that people in different parts of the country should be able to access different solutions to zero-carbon heating.

Prof Rebecca Willis from the University of Lancaster, who served as the expert lead on this topic, said she found the results “quite striking”:

“If you look at what the assembly members wanted, they really emphasised a focus on tailored solutions and choice. So they were favouring more locally based solutions and more players in the energy market, rather than a sort of top-down, national-level…solution.”

When considering retrofits, the members were in favour of upgrading houses all in one go; what Willis calls a “big bang” for each house, rather than upgrading gradually over a longer period.

“That was conditional on there being finance and support in place for householders to do that,” Willis added. However, there was only a slight preference for “all in one go” retrofitting (56% vs 44%) and members also stressed the importance of personal choice.

In terms of policy recommendations, a majority of members “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that 19 housing policy measures should be part of how the UK gets to net-zero.

Among these measures was strong support for a ban on the sale of new gas boilers from 2030 or 2035.

This chimes with the latest progress report to the government on net-zero from the CCC, which said the government must set a clear direction for ”phasing out installation of new gas boilers by 2035 at the latest”.

In total, the assembly examined policy solutions in five areas (brackets show percentage of members that agree or strongly agree with the policy compared with those that disagree or strongly disagree):

1.Information

- Information and support funded by government (83%/9%)

- Information and support provided by government (72%/6%)

- Carbon MOTs for houses (63%/29%)

2.Fairness and consumer protection

- Simpler consumer protection measures (92%/3%)

- Government help for everyone (69%/20%); Government help for poorer households (68%/23%)*

- Raising money through taxation and government borrowing (65%/34%); Raising money through adding to all householders energy bills (54%/18%)*

3.Standard setting

- Ban sales of new gas boilers (86%/9%)

- Changes to product standards applied to energy-using products to ensure they are more efficient and “smart”(91%/3%)

- Requirements each home to reach a certain level of energy efficiency before selling or renting (65%/17%)

4.Incentives

- Changing council tax or stamp duty so that you pay less tax for a home that has lower emissions (63%/25%)

- Green mortgages at cheaper rates to people in lower carbon homes (63%/17%)

- Government-backed loans with low or no interest for home improvements (54%/4%)

- Removing or reducing VAT for energy efficient or zero-home product (83%/12%)

5.Roles and powers

- Changing energy market rules to allow more companies to compete (86%/6%)

- Support for smaller organisations (94%/0%)

- Local plans for zero carbon homes (89%/3%)

- Enforcing district heating networks (66%/18%)

For the measures marked with an asterisk, these two approaches were also compared to each other. For example, people preferentially chose (43% support vs 34%) government help for “everyone” over the poorest households.

Raising money though adding to energy bills was also favoured over taxation and borrowing, although neither option was particularly popular (23% support vs 14%).

Attendees speak at the Climate Assembly. Credit: Fabio De Paola / PA.

Food, farming and land use

Thirty-five assembly members were picked at random to scrutinise food, farming and land use in the UK and how practices might need to change in order to reach net-zero emissions.

On weekend two of the assembly, these members heard “a wide range of views” on how best to manage food, farming and land-use in the UK, the report says.

After discussing the evidence, they came up with eight overarching “considerations” – themes that the government should bear in mind when making decisions about food.

According to the report, these include:

- Provide support to farmers – including financial and professional or skills-focused support.

- Information and education – from an early age about “greener and healthier eating habits”. This category also included suggestions for “carbon footprint labelling”.

- Use land efficiently – including “use the land differently to absorb more carbon” and “planting forests not trees”.

- Rules for large retailers and supermarkets – including reducing food waste and packaging.

- More local and seasonal food – including active promotion and support of local, seasonal and home-grown food options.

- Make low carbon food affordable – including “mak[ing] low carbon, healthy and home cooked food affordable (and vice versa)”.

- Some, just less, meat

- Part of planning policy and new developments, including allotments

The considerations are ranked by their support from the assembly members. For example, 89% chose providing support to farmers as a priority, whereas 29% of members chose eating less meat as a priority.

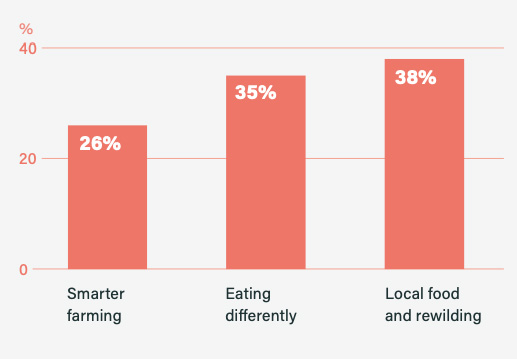

The members were then asked to vote on what kind of future they would like to see for the UK’s food and farming. They were given three future scenarios to choose from, which included:

- Smarter farming – a scenario involving “making farming more efficient and using more land to store carbon”. It does not require the public to change their eating habits.

- Eating differently – a scenario involving “farmers, retailers and individuals taking steps to reduce food waste and choose lower-carbon foods”. This scenario involves the public eating 20% less red meat and dairy.

- Local food and rewilding – a scenario of “fundamental change in food systems and landscapes, towards local production and more space for biodiversity”. This scenario involves the public eating 40% less red meat and dairy.

The assembly was asked to vote on their first preference by secret ballot. The results (shown in the chart below) find that “local food and rewilding” was the most popular scenario, with 38% of members choosing it as their first preference.

Assembly members’ first preference for the future of food, farming and land-use in the UK. Credit: Climate Assembly UK (2020).

Assembly members said a switch to local food and rewilding was “overall a good option, just [with] a few extreme aspects”. One member said “having more local foods will reduce costs and the food will be fresh”, while another said the scenario would have “health benefits from eating less red meat, dairy and processed foods”, according to the report.

The scenario was also perceived to be the most radical in terms of reducing emissions, the report says. Some members suggested it would have the “largest impact on reducing carbon emissions”, the report says.

However, other members felt that the 40% reduction in meat and dairy included in the scenario was “too much”, the report says. One member said: “For that kind of fundamental change, 30 years is not long enough – behaviours cannot change so radically.”

The “eating differently” scenario received the second highest level of support. Members said the level of dietary change in this scenario was “realistic” given that some people in the UK are already switching to plant-based diets, the report says.

Others, however, felt the “eating differently” scenario did not go “far enough”, the report says. One member said: “Does it go far enough? 20% less red meat and dairy may not reduce enough carbon emissions.”

The “smarter farming” scenario received the lowest level of support, with just over a quarter of the members picking it at as their first preference.

Assembly members said this scenario “falls short” of the action needed to reduce climate change, the report says. One member said “it doesn’t tackle red meat and dairy consumption, therefore, will carbon emissions be reduced enough?”, while another said “I feel it’s unrealistic to reach net-zero if there is no consumer change”.

In addition, some members said it was “unfair” that “all the pressure to change is on the farmers” rather than consumers, the report says.

Prof Lorraine Whitmarsh, an environmental psychologist specialising in climate change from the University of Bath, told the press briefing:

“There was a lot of support for farmers and concern that certain types of farmers – livestock farmers, for example, might be penalised.”

The assembly members were also asked to consider various policy options for reducing emissions from the food and farming production.

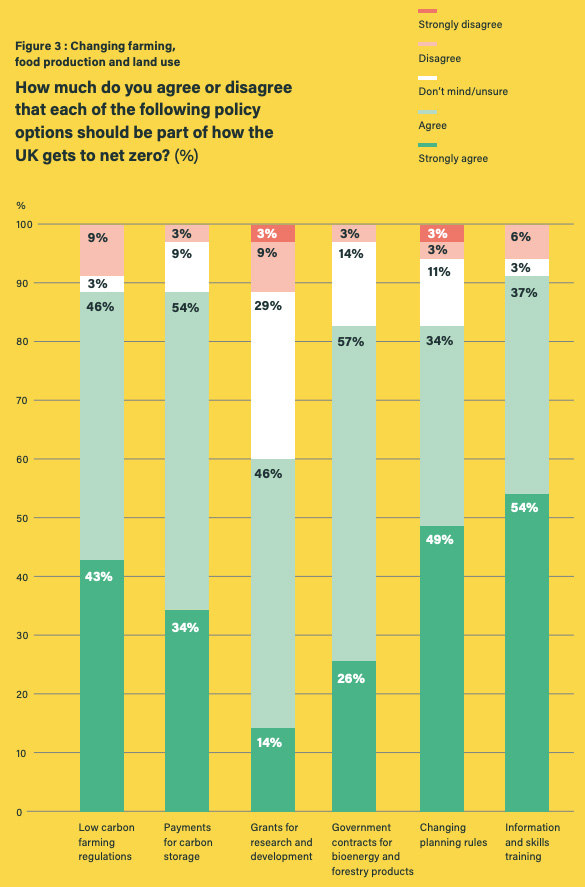

The chart below summarises how the members felt about different policy options, including low-carbon farming regulations, payments for carbon storage, grants for research and development, government contracts for bioenergy and forestry products, changing planning rules and information and skills training.

On the chart, colour is used to show the proportion of members that strongly agree (dark green), agree (light green), disagree (pink) and strongly disagree (red) with the various policy options. (White is also used for members who say they do not mind or are unsure.)

Assembly member acceptance of various policy options for reducing emissions from food, farming and land use in the UK. Credit: Climate Assembly UK (2020).

The chart shows that assembly members are most strongly in favour of policies that improve information and skills training for those that manage the land, such as farmers.

Members described these policies as “common sense” and a “no brainer”, the report says. According to the report, one member said:

“Education is the basis for everything, especially if the government is going to make changes. With farming practices, [it] will need a lot of education and training.”

Around half (49%) of assembly members were also in favour of policies that involve “changing planning rules so that healthy food can be produced sustainably in a wider range of areas, including in urban areas and buildings”, the report says.

Some assembly members said they “can’t see a negative with this option”, the report says.

In contrast, policies for grants for research and development into making agricultural practices more sustainable or reducing the costs of lab-grown meat received the lowest amount of support.

Of lab-grown meat, members said it could “divert attention away from lower carbon options such as veganism” and that it might “take jobs from farmers”, according to the report.

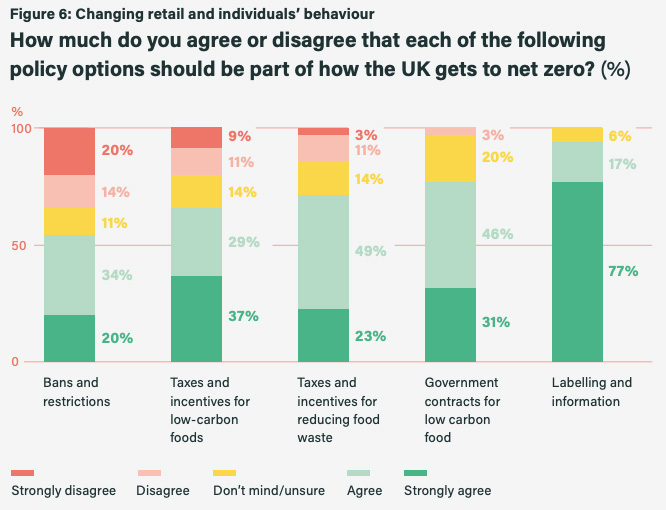

In addition, assembly members were asked to consider various policy options for changing individuals’ and retailers’ behaviour.

The chart below summarises how the members felt about different policy options, including bans and restrictions, taxes and incentives for low-carbon foods, taxes and incentives for reducing food waste, government contracts for low-carbon food and labelling and information.

On the chart, colour is used to show the proportion of members that strongly agree (dark green), agree (light green), disagree (pink) and strongly disagree (red) with the various policy options. (Yellow is also used for members who say they don’t mind or are unsure.)

Assembly member acceptance of various policy options for changing retail and individuals’ behaviour towards food in the UK. Credit: Climate Assembly UK (2020).

The chart shows that assembly members were most in favour of policies that involve “labelling on food and drink products showing the amount of emissions that come from different foods”.

Assembly members described these measures as “instantly impactful” and “not controlling”. According to the report, one member said: “It doesn’t restrict choices, but educates people.”

Bans and restrictions on the most carbon-emitting food types, including red meat and food transported by airplanes, received the lowest level of support.

Some members felt bans on certain foods would be “too harsh”, the report says. One member said: “Restrictions [are] okay, but not a ban – [this is] likely to damage businesses (butchers, shops, not just farmers).”

Consumption of goods and services

Thirty-five assembly members were picked at random to scrutinise what the UK buys and how this contributes to emissions. The report says:

“The things we buy are linked to climate change because they use energy and some of that energy comes from fossil fuels like oil, coal and gas.”

The group first formulated and agreed a set of key considerations that the government should bear in mind for consumer goods. Of the 14 they produced, the five with the highest priority were (the brackets show the percentage of assembly members that chose that consideration as a priority):

- Education and information for consumers – including “good, clear, accessible and understandable information, so people understand what’s going on and the impact of their choices” (74%).

- Long-term commitment from government and parliament – including “long-term cross-party commitment from parliament and a “permanent citizens’ assembly to oversee the work of government” (69%).

- Regulate and incentivise companies to produce things that last longer – including “incentivise companies to produce things that last longer” and “clear labelling of products to provide information (and choice) to consumers (60%).

- Benefit research, manufacturing and development in UK (46%)

- Place controls and restrictions on advertising of environmentally damaging products, and label them clearly as such (34%)

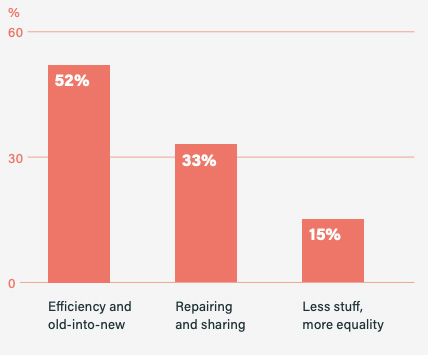

The members were then asked to vote on what kind of future they would like to see for the UK’s consumer patterns. They were given three future scenarios to choose from, which included:

- Efficiency and old-into-new – a scenario involving “businesses making products using less energy and materials, and turning old products into new ones”. This scenario would require the public to keep their products in condition, to rent more products instead of owning them and to recycle more.

- Repairing and sharing – a scenario involving “making products that last longer, and people renting/sharing more and owning less”. This scenario would require the public to buy new products half as often, to use fewer disposable items and to recycle more.

- Less stuff, more equality – a scenario involving “people earning less and buying less, with them spending more time fixing and making things”. This scenario requires individuals to be taxed more if they are on higher incomes, work in “more flexible ways”, including home working, in addition to using less products and recycling more.

The assembly was asked to vote on their first preference by secret ballot. The results (shown in the chart below), show that “efficiency and old-into-new” scenario was the most popular, with more than half of the assembly members choosing it as their first preference.

Assembly members’ first preference for the future of consumption in the UK. Credit: Climate Assembly UK (2020).

Assembly members said a switch towards more efficiency and product sharing “makes more sense” for the UK. One member said: “Renting for specific goods can be great, for example, children’s shoes renting costs less and [is] better for the environment.”

On the other hand, the “less stuff, more equality” scenario received the least support. Some members thought the idea of working less was “counterproductive”, according to the assembly.

One member said there would be “more social unrest if people have more time available” and another said there was a “risk that having more spare time will lead to more consumption”.

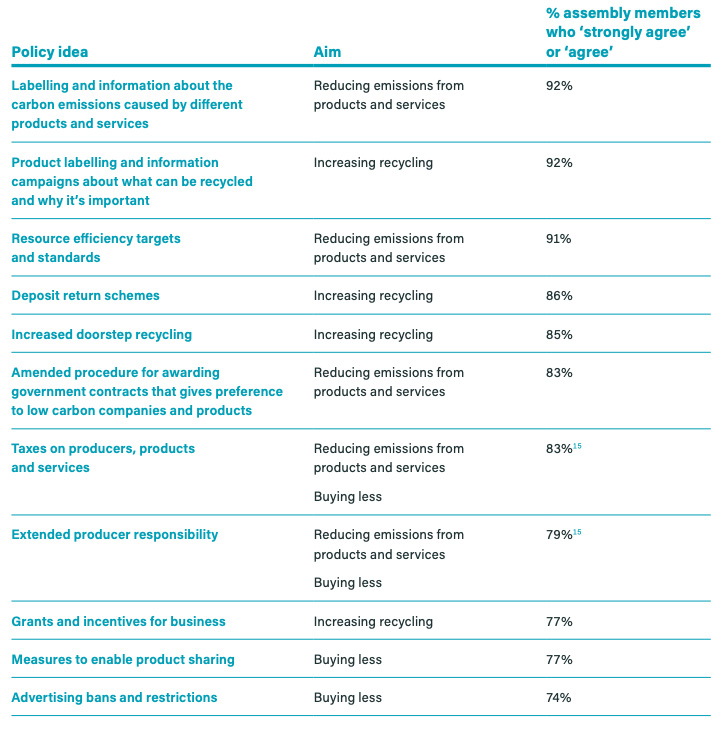

The assembly members were also asked to consider various policy options aimed at reducing emissions from products and services, convincing people to buy less and Increasing levels of recycling.

The table below shows the 13 most popular policy ideas across each of the three aims. The right-hand side of the table shows the proportion of assembly members who strongly agreed or agreed with each policy idea.

Assembly member acceptance of various policy options for reducing consumption in the UK via reducing emissions from products and services, increasing recycling and buying less. Credit: Climate Assembly UK (2020).

The table shows that the two most popular policy ideas include adding labels to goods to give information about their carbon footprints and adding labels to show what can be recycled.

Assembly members said they were in favour of labels because they “give choices”, according to the report, but are still “voluntary”.

In contrast, members did not back policy ideas involving voluntary agreements, changes to income tax or working hours, personal carbon allowances, recycling requirements or “pay-as-you-throw” schemes. The report says:

“Their concerns included that measures would be ineffective or impractical, that they would penalise the less well-off, or that they would have unwanted side-effects such as an increase in fly-tipping.”

Electricity

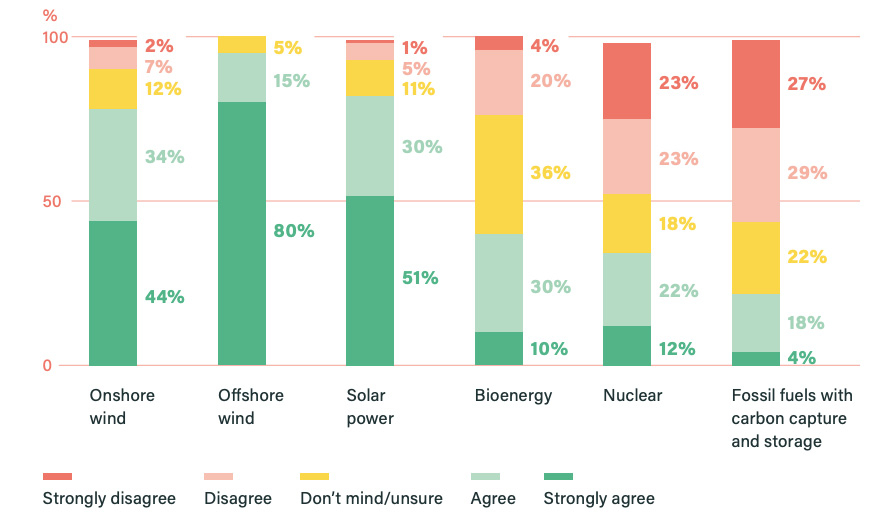

All assembly members heard evidence, deliberated and voted on six main ways of generating electricity in the UK.

These were onshore and offshore wind, solar, bioenergy, nuclear and fossil fuels with carbon capture and storage (CCS). They also heard limited evidence on more niche technologies, including hydropower, tidal, wave and geothermal.

They had less time on this topic than other areas and, therefore, primarily focused on a single question, namely which of these technologies should be part of how the UK gets to net-zero.

Overall, there was very high support for wind and solar power, as the chart below demonstrates. Offshore wind, in particular, had no disagreement at all from assembly members.

Assembly member acceptance of different electricity generation technologies for achieving net-zero in the UK. Credit: Climate Assembly UK (2020).

When asked to rank technologies in order of preference, 65% of participants placed offshore wind first. The next most popular was solar power on 12%.

When justifying their support for these technologies, members tended to describe these renewables as “proven, clean and low cost”, according to the report. Offshore wind was particularly popular due to being “out of the way”.

However, according to the report, assembly members were “much less supportive” when it came to bioenergy, nuclear and CCS. These results are in line with the government’s own polling on this subject.

Willis told a press briefing there was “a lot of scepticism” on nuclear power, “even though that’s been around some time”. The concerns being raised tended to focus on cost, safety and issues around waste storage and decommissioning.

At the same briefing, Stark said that, overall, he was “pleasantly surprised” by the similarities between the conclusions emerging from the assembly and the CCC around pathways to net-zero.

However, he said that CCS was the topic that saw the biggest discrepancy between the committee and the assembly members, for many of whom this would have been “a relatively new concept”.

The main concerns from participants around CCS were that it “sidesteps” the wider issue of greenhouse gas emissions and enables the continued use of fossil fuels into the future, as well as what they saw as the potential for leakage from storage sites.

Crucially, there was also a considerable gap between the government’s plans to deploy CCS and the reservations of assembly members. Stark said this was “one of the very valid concerns” to emerge from this process. He told a press conference:

“If we are going to have CCS as part of the UK’s journey…then there is a task for the government…Perhaps also, [for] industry, [in order] to win round people on why it’s safe technology and it can work.”

Greenhouse gas removal

On the penultimate weekend of the Climate Assembly, all members heard evidence, discussed and voted on the best options for removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere (known as “GGR”).

By the middle of the century, even if extensive decarbonisation policies are in place, there will be some emissions remaining from sectors such as aviation and agriculture.

As with electricity generation, members heard about a variety of potential technologies and approaches, focusing on the single question of which should be part of the net-zero transition.

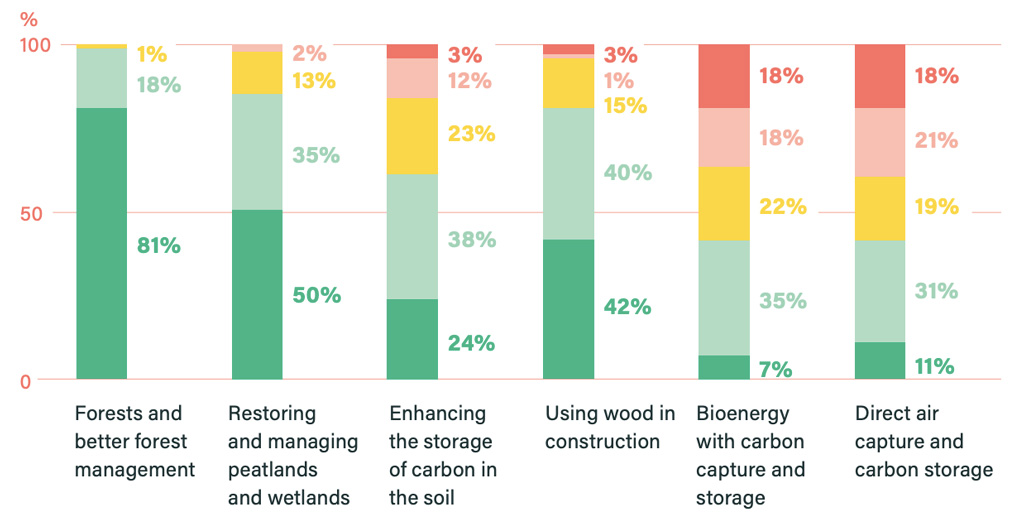

The topics they heard about were forestry, restoring peatlands and wetlands, enhancing soil carbon storage, bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) and direct air carbon capture and storage (DAC).

As the chart below shows, natural solutions – and particularly afforestation and forest management – were the most popular approaches.

Assembly member acceptance of different GGR technologies and approaches for achieving net-zero in the UK. Credit: Climate Assembly UK (2020).

The strong support for forestry came despite the fact that, according to Watson, during the process the “uncertainties” around such “nature-based” solutions were emphasised. Some participants did mention the possibility of trees providing long-term storage.

As with CCS (see Electricity section above), there were low levels of support for both BECCS and DAC, with reasons given about storage safety concerns and enabling the continued use of fossil fuels.

Green recovery

The Covid-19 pandemic saw a late addition to the climate assembly’s agenda. The report says:

“At the request of both parliament and assembly members themselves, space was made for consideration of the changed context for reaching net-zero created by the Covid-19 pandemic, and its impacts.”

On the final assembly weekend on 16 May – while the UK was under strict lockdown – assembly members listened to one final expert presentation delivered by Chris Stark, chief executive of the CCC.

The presentation aimed to help members consider: whether the UK should pursue an economic recovery from coronavirus that was in line with its net-zero target; whether the virus should spark a shift towards lower-carbon lifestyles in the future; and whether the virus had made them think or feel differently about how the UK should get to net-zero. The report says:

“Assembly members’ views on these questions are significant. There is no other group that is at once representative of the UK population, and well-acquainted with the sorts of measures required to reach net zero.”

Assembly members were asked to vote in secret on two statements.

The first statement was: “Steps taken by the government to help the economy recover should be designed to help achieve net-zero.”

To this, 42% of assembly members strongly agreed, 37% agreed, 12% were unsure, 3% disagreed and 6% strongly disagreed, according to the report.

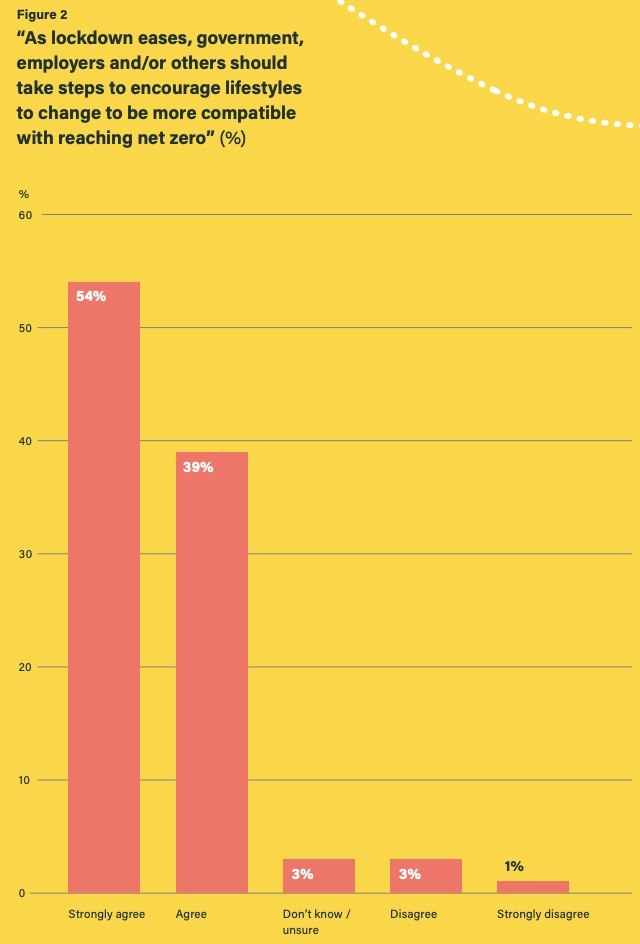

The second statement was: “As lockdown eases, government, employers and/or others should take steps to encourage lifestyles to change to be more compatible with reaching net-zero.”

The chart below shows how participants responded to this statement. More than half strongly agreed – and just 1% strongly disagreed, according to the report.

Assembly members’ reaction to the statement: “As lockdown eases, government, employers and/or others should take steps to encourage lifestyles to change to be more compatible with reaching net zero”. Credit: Climate Assembly UK (2020).

In the discussions prior to the vote, one member said: “Any money spent bailing out dying fossil fuel industries (the aviation industry, north sea oil) is money wasted on industries that won’t survive anyway.”

Another said: “Feels [like] the government should bail out companies with green plans and, in turn, their taxes will fund the government.”

Several members said the pandemics provided an “opportunity for change”, according to the report. One said:

“The public is learning how to deal with change and we should take advantage of this developing attitude to introduce and enact the substantial changes that will be required.”

The assembly members were also asked to think about how the pandemic had shaped their views of getting to net-zero emissions in the UK.

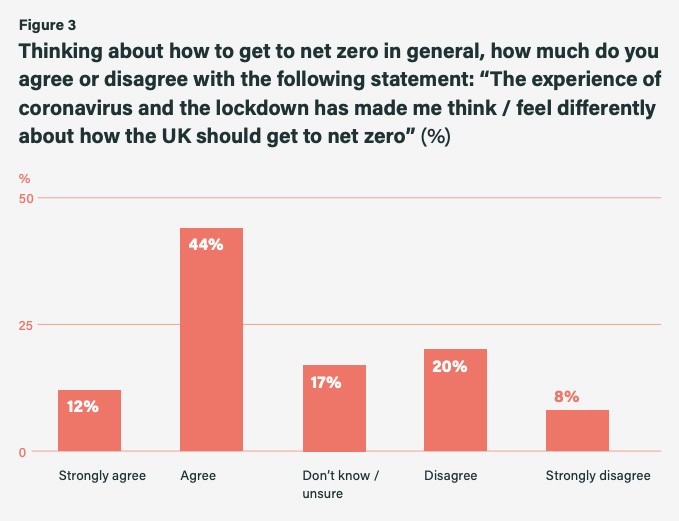

The chart below shows how assembly members responded to the statement: “The experience of coronavirus and the lockdown has made me think/feel differently about how the UK should get to net-zero.”

Assembly members’ response to the statement: “The experience of coronavirus and the lockdown has made me think/feel differently about how the UK should get to net-zero”. Credit: Climate Assembly UK (2020).

The chart shows that 58% of assembly members either agreed or strongly agreed that the pandemic had made them view how the UK should get to net-zero differently.

Some members described the pandemic as “a wake up call”, the report says. One member said:

“[I] realise it’s much more important [now] – this catastrophe is easier to deal with than climate change.”

The pandemic had the biggest impact on perceptions of how travel could contribute to the net-zero target – with 73% of assembly members agreeing that the virus had changed their opinions on this sector, according to the report. One member said:

“We can’t fly. I would normally fly three times a year to go on holidays, but this lockdown has made me think about flying.”

Others, however, said that the pandemic had not changed their views, but, the report says, “emphasised the importance of views they already held, or provided evidence for them”.

[See Carbon Brief’s tracker which is recording how governments around the world are implementing “green recovery” measures in response to Covid-19.]

Net-zero date and additional proposals

On the final weekend of the assembly, all the members discussed any additional recommendations they wanted to make to the government and parliament.

They voted in favour of another 39 recommendations, many with very high levels of support (more than 90%) including ensuring the net-zero transition is a non-partisan issue and avoiding the “offshoring” of UK emissions to other parts of the world.

Crucially, they rejected two proposals, both regarding a change in the net-zero target date. (One proposed simply setting a more ambitious date and another suggested the same, but without making it legally binding).

In both cases, slightly more people (39% and 40%) opposed the idea than supported it (35% for both).

In a press briefing, the expert leads noted that this result likely reflected the fact that participants had not been briefed extensively on such a date change. This is reflected in the sizable proportion (24% and 28%) of people who chose “don’t mind/unsure”, they said.

What happens next?

The report is intended to now provide tools for parliament to scrutinise the government’s progress towards net-zero.

The six select committee chairs that commissioned the report will provide responses about what they intend to do in response and there will be a statement in parliament on the launch.

Business secretary Alok Sharma will soon be in front of the Environmental Audit Committee answering questions on the government’s initial reaction to the report. There will also be a debate in parliament on the findings.

Chris Shaw, parliamentary director for the Climate Assembly, told a press conference before the report’s launch:

“We are doing an awful lot of briefing of stakeholders, of officials, of MPs and peers over the next few days so let’s hope it’s the start of a big debate.”

-

Q&A: How the ‘climate assembly’ says the UK should reach net-zero

-

Q&A: What are the key recommendations of the UK’s ‘climate assembly’?