Q&A: How China is using nuclear power to reduce its carbon emissions

Anika Patel

08.14.23Anika Patel

14.08.2023 | 3:04pmChina recently approved the construction of six more nuclear reactors, cementing its status as the world’s fastest-growing nuclear power producer.

Despite only starting to develop the technology in the mid-1980s, decades later than some other major economies, China is expected to have the world’s largest nuclear fleet by 2030.

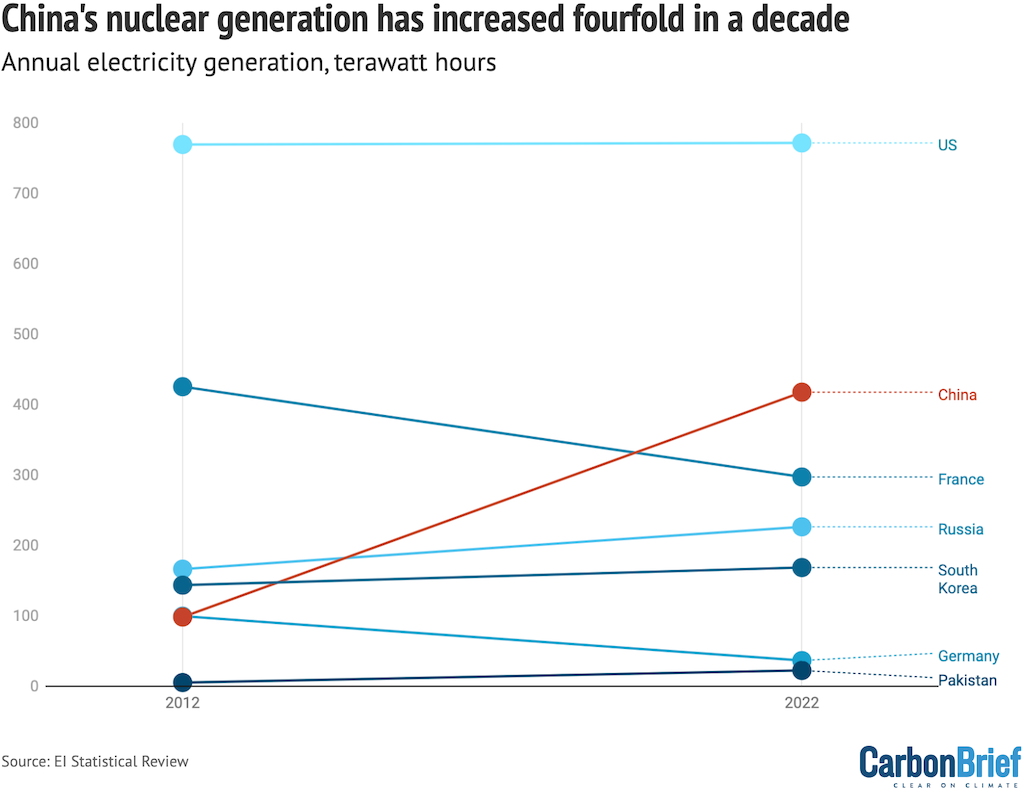

Electricity generation from nuclear power plants has already increased nearly fourfold in the past decade, with China overtaking France to become the world’s second-largest producer.

China is also looking to export its nuclear power technology – despite setbacks to these plans in the UK and Argentina – with Pakistan seen as the latest “springboard” for further growth.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief looks at the trajectory of China’s nuclear development and what’s driving its strategy for the technology.

- How much nuclear power is China building?

- Is nuclear power an important part of China’s climate plans?

- Is China exporting its nuclear power technology?

How much nuclear power is China building?

China began building its first nuclear plant in 1985. The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES) estimates that it will have the world’s largest nuclear fleet by 2030.

For now, China is now the world’s second largest nuclear energy producer behind the US, having overtaken France in 2020. By the end of June 2023, China had an installed capacity of 57 gigawatts (GW), according to official data.

China remains behind the 96GW installed in the US – for now. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) says China is the “world’s fastest expanding nuclear power producer”.

It has 23 nuclear units under construction, totalling more than 21GW of additional capacity. In addition, China approved 10 new reactors in 2022 and another six units in early August 2023.

China accounted for two of the six reactors completed globally in 2022, as well as five of the eight units where construction was started, according to the World Nuclear Association (WNA).

This meteoric rise has seen China’s nuclear output increase more than fourfold in the past decade, from 98 terawatt hours (TWh) in 2012 to 418TWh in 2022, shown in the figure below (red line).

China is one of only a handful of countries along with Russia (+60TWh), South Korea (+25TWh), the United Arab Emirates (+20TWh) and Pakistan (+17TWh) to see significant growth in the period.

Despite this growth, nuclear still makes up only 5% of China’s electricity mix. This is below nuclear’s 9% share of global supplies in 2022.

China has also become a leading nuclear innovator. It is the first country to build a Generation IV reactor, connecting a demonstration project to the grid in 2021. Small-scale nuclear-powered district heating projects are running in Shandong and Zhejiang.

Dr Shengke Zhi, director for growth and development at consulting firm Wood, tells Carbon Brief that China’s Generation IV technology still has a long way to go. “Generation III is still the primary choice for China’s mega-rollout of nuclear capacity,” he says.

Is nuclear power an important part of China’s climate plans?

China’s nuclear capacity is expanding, but there are question marks over how fast it will grow. China could add as many as 10 reactors a year, reaching a capacity of 300GW by 2035, according to China Nuclear Energy Association forecasts reported by Bloomberg last autumn. The OIES cautions that a total of 100GW by 2030 is “more likely”.

Dr Philip Andrews-Speed, senior research fellow at the OIES, described nuclear energy to Carbon Brief as a “fuel of convenience” for China, pointing out that it meets the country’s concerns around energy security and the need to decarbonise.

“Beyond net-zero considerations,”, Zhi says, “nuclear energy is necessary to develop a diversified energy mix, create more jobs and upgrade its supply chain”.

China has been able to build new nuclear plants much more cheaply than many other countries. Analysts put the costs per kilowatt of installed nuclear capacity in China at around one-third of those in the US or France, Bloomberg reported.

(The International Energy Agency estimates that electricity from nuclear power costs $65 per megawatt hour (MWh) compared with $105/MWh in the US and $140/MWh in the EU.)

Zhi pointed to China’s “design-one build-many” approach to nuclear construction as one reason for its success. A 2018 paper in the journal Sustainability suggested nuclear power in China could become more competitive than coal by 2030.

Zhi agrees with this assessment. Coal power is getting increasingly expensive, “especially due to carbon pricing and other environmental fees”, he says.

Policymakers have used a familiar toolkit to encourage development. Mark Hibbs, senior fellow at thinktank Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, identified financial subsidies, access to decision-makers and favourable price-setting as key advantages.

He wrote that the “guaranteed tariff paid to producers for nuclear power…has been higher than the rate for either coal-fired or hydroelectric power”. He also quoted a Chinese nuclear industry executive, who said in 2015: “We watch this carefully…if the government were to take this away from us, the future of our business would be in a lot of trouble.”

The WNA points out that safety questions have slowed China’s nuclear ambitions. Following the Fukushima Daiichi accident, China temporarily suspended approvals of new power plants, to review concerns over safety and river pollution, according to Andrews-Speed.

However, the Chinese government called for “actively developing nuclear power” – with a “steady pace” of construction – as part of its 2021 action plan on peaking CO2 before 2030.

Is China exporting its nuclear power technology?

In 2019, Reuters reported one senior industry official saying China aims to build as many as 30 overseas nuclear power units by 2030.

“I don’t see China meeting this goal”, Andrews-Speed tells Carbon Brief. He attributed this to China’s domestic focus: with around 23 units under construction and as many as 156 more proposals for future plants, nuclear companies are “very much busy at home”.

The UK, Argentina and other countries had signed deals to cooperate with China on domestic nuclear reactors, but security concerns in the UK and significant delays in Argentina have limited full cooperation.

In Pakistan, eight reactors built with Chinese assistance are either in operation or under construction, boosting generation capacity in a country that has been beset with shortages.

China is aiming to use its nuclear projects in Pakistan as a “springboard” to further export growth for the technology, Nikkei Asia reported in July.

Nevertheless, China’s ambitions to increase its nuclear technology exports are limited, Andrews-Speed writes, by Russia’s influence in the sector, the fact that China is not yet a party to the IAEA Vienna Convention, and the fact that it does not take back used fuel.