Q&A: How can countries stop subsidies harming biodiversity?

Orla Dwyer

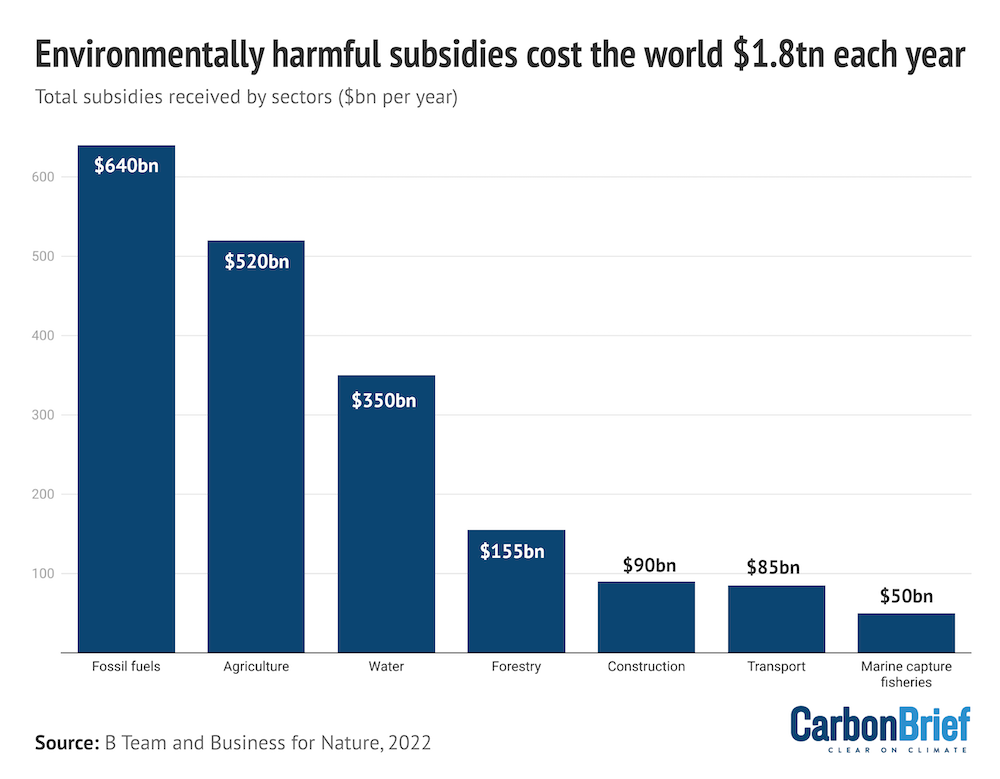

05.23.23Subsidies that harm nature and the environment cost the world an estimated $1.8tn each year – the equivalent of the entire GDP of Canada.

Governments funnel this money into supporting fossil fuels, agriculture and other sectors which can have negative impacts on biodiversity.

Countries have signed up to a number of targets to cut down these subsidies, including in a recent global agreement to reduce biodiversity-harming subsidies by at least $500bn by 2030.

But experts say there is still a long road ahead to reduce the ways in which governments harm nature and ecosystems, such as lowering the cost of fossil fuels, fertilisers and pesticides alongside other actions including building roads in biodiverse areas.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief explains how these subsidies can cause damage and the hurdles standing in the way of getting rid of them.

- What are ‘harmful subsidies’ to biodiversity?

- What harm do these subsidies cause?

- What are the barriers preventing the end of harmful subsidies?

- How do countries plan to reduce harmful subsidies?

- Can biodiversity-harming subsidies be reduced by $500bn by 2030?

What are ‘harmful subsidies’ to biodiversity?

There are two key types of harmful subsidies – those that damage the environment and those that harm biodiversity.

In general, harmful environmental subsidies impact our surroundings whereas harmful biodiversity subsidies affect plant and animal life. But there is overlap between the two.

There is no standard definition for subsidies that harm biodiversity. They are essentially government incentives that supplement income or lower costs for consumers or producers, but end up damaging biodiversity in some way.

Agriculture, fishery and energy subsidies are most commonly termed “harmful”, but damage can also be caused by subsidies for forestry, infrastructure, transport, construction and water.

Water subsidies can lead to overuse, for example, which can deplete water bodies and damage habitats.

Ronald Steenblik, subsidies expert and senior technical adviser to the Quaker United Nations Office, a non-governmental organisation representing the Quaker religious group at the UN, notes the overlap between subsidies that harm the environment and those that harm biodiversity.

He tells Carbon Brief that some of this overlap is because an action that increase CO2 emissions “ultimately affects the climate – and climate is a feedback loop on biodiversity”.

Steenblik co-authored a 2022 report that estimated the global annual cost of environmentally harmful subsidies.

A study published last year found that land- and sea-use change have been the biggest drivers of recent biodiversity loss, followed closely by the exploitation of natural resources through activities such as fishing or hunting. But, it added, climate change is “probably the most rapidly intensifying threat to biodiversity”.

Prof Rashid Sumaila, a professor of ocean and fisheries economics at the University of British Columbia, says that using public funds for any activities connected to exploiting biodiversity is “like pouring petrol on fire”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“When you look at biodiversity, when you look at fish, even if you look at climate, all the things related to the environment – they’re essentially common property.

“You don’t own the air, most of the time the fish don’t respect our borders. Biodiversity is a general good. Whenever you have that situation, even without subsidies, it’s really difficult to manage because nobody really owns it and there’s all this competition to grab and turn it into human capital.

“If, on top of that, you are given free money, public funds, to do any of the activities connected to exploiting biodiversity, you are going to do even more of it.”

What harm do these subsidies cause?

A lot of government funding for different sectors is “potentially environmentally harmful”, according to a working paper published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) last year.

It added that the negative impacts of subsidies are often “unforeseen, undervalued or ignored in the policy process”.

Prof Alan Matthews, a European agricultural policy expert at Trinity College Dublin, says that while there are a wide range of potentially harmful subsidies, there are four key sectors “where most of the damaging subsidies can be found”. These are energy, agriculture, forestry and fishing.

The OECD report, which Matthews co-authored, highlights a few specific examples of potential harm, such as lower-cost fuel being sold for agriculture and other industrial activities.

Another common example, the report points out, is setting low VAT rates on food, including meat and dairy products – which cause high levels of greenhouse gas emissions.

Certain supports can distort prices and alter production and consumption patterns, the OECD paper says.

Most governments only consider tax exemptions and government expenditures when accounting for their harmful subsidies. However, negative impacts can also arise from a lack of government action, such as not applying excise taxes on fuels.

This can lead to prices not reflecting the environmental and social costs of a product or activity, creating implicit subsidies. The effects of this type of inaction are harder to quantify, experts say.

Subsidies can cause both direct and indirect harms. Direct impacts include converting forested land to grow biofuel crops or building roads in biodiverse areas, while indirect effects include increasing CO2 emissions.

These impacts occur over a range of timescales. More immediate effects include land conversion, road building and oil spills, while delayed impacts include pollution leading to passing critical ecological thresholds over time.

Not all subsidies are equally harmful. Hydrological power generation, the report notes, produces renewable energy, which can lead to less fossil-fuel use. However, it can also negatively impact local water supply and species.

And some subsidies may appear positive or neutral at first, but end up having negative effects down the line – such as subsidies for the modernisation of fishing fleets.

Fishing subsidies

Government support for fishing can lead to overfishing and encourage illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. These actions deplete fish stocks and damage marine habitats.

Sumaila says that some subsidies, including paying part of the cost of new boat equipment or engines, may have “good intentions”. But, he adds:

“The fish doesn’t care about our good intentions. If you overcatch it, you overcatch it.”

Last year, the World Trade Organization (WTO) reached an agreement to curb fishery subsidies. Sumaila welcomes the deal, but adds:

“The key disappointment for me is that they avoided naming specific subsidies. This makes it too complicated…The implementation is not going to be easy.”

Steenblik agrees that the agreement is “not as ambitious” as it could have been. He tells Carbon Brief:

“It shows that for the first time the WTO can be a place where an agreement that’s motivated mainly by environmental reasons can get negotiated.

“It’s unlike when the agricultural agreement was signed. It was all about trade. It was all about the distortions to trade caused by the subsidies. In the case of the fishery subsidies agreement, it’s mainly about the effects of the subsidies on illegal fishing and overfishing.”

He adds that there is a challenge in convincing people to cut subsidies on environmental reasons alone:

“With fisheries it was easier to understand the relationship between subsidies and overfishing and the decline of fish stocks…Fish subsidies are a whole order of magnitude smaller than agricultural subsidies globally. It was less of an urgent thing for a lot of countries, from the standpoint of the budgetary impact.”

Agricultural subsidies

Governments provide many forms of support to cut input costs and enhance yields in the agricultural sector.

Support can influence decisions ranging from crop choices, tillage practices and even reasons for entering or leaving farming. These actions influence biodiversity in different ways. For example, subsidies for pesticides and fertilisers can lead to overuse and inefficient application, impacting local ecosystems and contaminating groundwater.

Steenblik previously worked on agricultural-subsidies analysis at the OECD. He says:

“Up until the early 2000s, one really felt as if there was progress being made in agricultural subsidies. For one, there had been the reductions that were required under the Uruguay Round [of WTO negotiations].

“And then in the EU, the US, Canada, several of the big OECD countries were basically saying ‘yeah, we get it, we should end the production-related subsidies and go towards trying to help out farmers directly through joint-income support or other types of support’.”

Matthews says that the EU’s agricultural policy is “certainly not beneficial to biodiversity” as it currently stands, but adds:

“I would argue it’s probably less damaging in the way the support is given to farmers than, let’s say, 20 years ago where it was much more linked to production.

“Farmers had to produce in order to get the subsidy under the CAP [Common Agricultural Policy]. That decoupling of support in itself has probably been somewhat advantageous.”

The OECD report adds that some government agricultural subsidies are beneficial, such as payments for farmers to plant trees or maintain ecosystems.

The UK this year released details about its new funding schemes for farms in England, which includes payments for different activities that benefit the environment. (For more on these schemes, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth Q&A.)

Other subsidies

Energy subsidies, usually held in the category of environmentally harmful subsidies, can also impact biodiversity.

The OECD paper notes that these can lead to oil spills and impact migratory birds from power lines and wind farms. All of the emission increases and environmental emissions also exacerbate climate change, a key threat to biodiversity.

There are a number of impacts from transport sector subsidies. These include forest and habitat fragmentation for road-building and also noise pollution.

Shipping can cause excess underwater noise, pollution and harm habitats and animals through the use of anchors.

What are the barriers preventing the end of harmful subsidies?

Experts tell Carbon Brief that there are a number of hurdles standing in the way of faster action to tackle harmful subsidies.

One major issue is that once a subsidy is in place, it can be difficult to remove. Matthews says:

“As soon as you provide a subsidy, there’s obviously a beneficiary. It can be farmers, it can be house owners, it can be local authorities who might get subsidies for road-building.

“To try to remove or repurpose those subsidies is clearly going to result in, if you like, ‘losers’. So it’s around the political economy issue of how to overcome that resistance to withdrawing a subsidy that a group or specific beneficiary has got used to receiving.”

He says that putting the responsibility for a certain subsidy in need of reform under a prime minister or president’s office, rather than a specific department, could prevent those who benefit from the subsidies having a “greater influence” in resisting reform.

Steenblik says the barriers to change include a short-term focus in politics and “also a bit of a lack of imagination”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“There are plenty of ideas out there on how to deal with any regressive nature of [removing harmful subsidies] through other feedback ways of providing targeted assistance to those who would be harmed by the prices. But they just haven’t figured out how to sell that.”

The OECD working paper on this topic lists a number of factors that can spur on reform. These include: shifting political priorities after an election or a major event; identifying problems with a subsidy’ financial crises leading to shuffled budgets; and public or stakeholder pressure.

Matthews adds that it is not as straightforward in many cases to simply “scrap the subsidy”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Very often, maybe it might be more sensible and certainly politically more feasible to ask ‘can we actually deliver the objective we’re trying to achieve in a way which is actually much less damaging to biodiversity?’

“I think that’s certainly the case in agriculture where you could certainly see opportunities to shift the way in which one provides support to farmers so that it actually has much less of a negative impact on biodiversity.”

How do countries plan to reduce harmful subsidies?

A range of global targets and goals exist to address and cut harmful subsidies. These include the UN Sustainable Development Goals and agreements under the WTO, G7 and G20 groups.

The Aichi targets, agreed in 2010 by countries under the Convention on Biological Diversity, set a goal to eliminate, phase-out or reform incentives harmful to biodiversity by 2020. The target also called for the development and application of positive biodiversity incentives.

However, this – like all of the Aichi targets – was ultimately not met.

At the UN biodiversity COP15 summit in Montreal late last year, countries established a new set of targets for protecting biodiversity. The agreement aims to identify incentives, including subsidies, that are harmful for biodiversity by 2025 and eliminate, phase out or reform them by 2030 – including a numerical target to reduce the incentives by at least $500bn per year by the end of the decade.

The target adds that this should be done in a way that is fair, effective and equitable. The first focus should be on the most harmful incentives and it adds that positive incentives should be scaled up to protect biodiversity.

A draft version of the COP15 target to reduce harmful subsidies included a mention of harmful “fisheries and agricultural subsidies”. But this explicit call-out did not make it into the final text.

Although the target forms part of how governments intend to reduce harmful subsidies, it is not legally binding.

In comparison to the cost of environmentally harmful subsidies, an estimated $78-91bn is spent globally to conserve and restore biodiversity each year, according to the OECD.

A UK government report on the economics of biodiversity published in 2021 notes that the downsides of environmentally harmful subsidies “vastly outweigh” any beneficial incentives.

Matthews says that “no government intentionally sets out to damage biodiversity”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“There’s always another objective behind the subsidy that a government is trying to achieve. We can debate whether that objective is legitimate, warranted, reasonable or whatever, but it can be to provide income support…[or] trying to help young couples get on the housing ladder.”

The OECD paper notes that identifying direct and indirect subsidies, deciding which ones are potentially harmful, quantifying the size of the subsidies and examining the extent of the harm are all different steps in the process towards ultimately reducing or removing them.

In 2014, countries under the CBD – which does not include the US – agreed to complete national studies to identify harmful incentives and subsidies, alongside opportunities for more positive measures.

The OECD paper says that, as of 2021, few countries have done so.

Can biodiversity-harming subsidies be reduced by $500bn by 2030?

Implementation was one of the core issues during the COP15 negotiations last year.

Much of the COP15 agreement’s plan to ensure the targets are acted upon appears to mirror the implementation schedule of the Paris Agreement. This requires countries to submit national climate plans, specifies dates for “global stocktakes” to take place and asks nations to “ratchet” up their ambition following reviews.

Countries are asked to revise their national biodiversity action plans to better align with the goals and targets of the new agreement before COP16, which is scheduled to take place in Turkey in 2024.

A separate decision on mechanisms for planning, monitoring, reporting and review of the COP15 agreement says that country reports continue to be a “core element” in assessing implementation.

National biodiversity strategies and plans are the main way in which the goals and targets are implemented on a country-by-country basis.

Clement Metivier, a senior policy adviser at WWF, told Carbon Brief at COP15 that the implementation plans are a big step forward from the Aichi targets. He said:

“It’s great to see a type of ‘ratcheting’ step included that allows countries to improve actions and efforts if implementation is not on track. But tragically, it’s only voluntary.”

The implementation document invites countries hosting the next two meetings of the CBD – in 2024 and 2026 – to consider organising talks to review progress towards implementation of the agreement made at COP15.

Under the COP15 decision, countries need to submit national reports on the measures taken to implement key targets and goals. The next report is due by the end of February 2026.

These national reports will give an insight into how well the aims of the global agreement are being put into action.

In terms of addressing the $500bn element of the goal, Steenblik notes that many government incentives do not involve “actual money flowing to fossil fuel producers”, but instead governments “underpricing” fossil fuels. He explains:

“A big chunk of the fossil-fuel and agricultural subsidies are not actual government money and therefore it’s not something that can be just switched over to supporting biodiversity.

“That’s why the target of reforming is not the full $1.8tn or whatever, it’s a smaller number. A big part of that isn’t necessarily going to lead to funds that the governments can then use for something else.”

The International Monetary Fund estimates that fossil fuel subsidies amounted to $5.9tn in 2020. Steenblik says commentary around subsidies sometimes claim “we can solve the whole problem by just taking this $6tn a year and shifting it to renewable energy.” He adds:

“This money is not being collected by anybody. It’s the underpricing of fossil fuels to consumers.”

Matthews says that there is certainly more awareness of “the crisis of biodiversity loss” at the moment, which may be a cause for optimism that “more will be done” this decade.

But there is no time for assumptions at this point, Sumaila says, adding:

“I think the world will do this only if we don’t assume that by having an agreement it’s going to happen. These countries are good at signing papers and going home and forgetting everything. We need to push hard. There are so many agreements, where do they take us?”