About half the country is being opened up to fracking for shale gas and oil today, various newspapers reported this morning. Here’s everything you need to know about UK fracking.

What’s shale gas?

Shale gas is normal gas, extracted from shale rock using a technique known as fracking, or hydraulic fracturing of the rock. Our full briefing on the fuel is here.

What has been announced today?

The government has opened the 14th onshore oil and gas licensing round. A licensing round is when firms get the chance to apply for exclusive rights to search for and extract oil and gas from beneath blocks of land measuring 10 by 10 kilometres.

The round announced today closes on 28 October this year. The last round was held six years ago when few had heard of fracking.

It is only four years since the first exploratory well to look for shale gas in the UK was sunk. Seismic tremors caused by early shale exploration operations in 2011 delayed the launch of the 14th licensing round, preparations for which had also begun in 2010.

Today’s announcement and any licenses handed out as a result do not grant permission to actually start fracking. Other regulatory permissions are required first – see below.

Which parts of the country are being opened up to fracking?

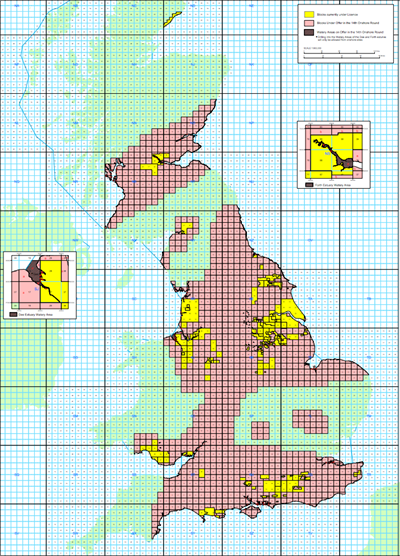

From today firms can apply for licences covering about 96,000 square kilometres of land. The UK covers 244,000 square kilometres – so that’s around two-fifths of the total. The area on offer is shown in pink on the map below. Including the yellow areas already licensed for exploration, about half of the country is available for fracking.

Source: DECC

Analysis from Greenpeace Energydesk shows the areas available for licensing include 10 of the country’s 13 national parks and the UK’s 10 largest cities. Could London could be fracked? We think it’s a long shot.

How much gas is there?

The British Geological Survey (BGS) has estimated how much shale gas is trapped in rocks under the Bowland shale in Lancashire, the Weald basin in Sussex and the Midland valley in Scotland. The Bowland shale has significant quantities of gas – an estimated 1,300 trillion cubic feet (tcf). The Midland valley is thought to have 80 tcf. The Weald has very little gas but an estimated 4.4 billion barrels of shale oil.

Only fractions of these quantities will be recoverable. Experience in the US suggests up to 10 per cent for shale gas and just a few per cent for oil, but take that figure with apinch of salt – it all depends on the geology of each location.

That means estimates for the recoverable quantity of gas range widely. The US Energy Information Administration says the UK has 5 tcf. The BGS says its 26 tcf. There is an estimated 7,299 tcf of shale gas technically recoverable around the world.

For comparison, the UK uses about 3 tcf per year – so we’re talking about something between 2.5 and 13 years worth of UK gas use.

Will firms be able to drill in national parks?

The government says there was “strong support” for an outright ban on fracking in all environmentally sensitive sites, in responses to a consultation that ended in March. It says it acknowledges public concerns but has not backed a ban.

Instead the government says applications to frack in national parks and areas of outstanding natural beauty “should be refused, except in exceptional circumstances and where it can be demonstrated that they are in the public interest”. The precise impact of this wording will remain unclear until tested during the planning process and ultimately in the courts.

Some other parts of the country will get special environmental consideration. Any firm wanting to frack in or near European protected areas will be subject to additional assessment requirements. These can have real impact. For instance Cuadrilla dropped plans to drill and frack at a site in Westby, Lancashire last October because it was close to a population of whooper swans, a European protected species. There is a large concentration of European protected areas in north west England.

Does the public support fracking?

Public opposition to fracking seems to be increasing the closer we get to actually having a shale gas industry. A Carbon Brief poll last summer found just 18 per cent would support a shale gas well within 10 miles of their home. The latest government survey found 22 per cent opposed to shale exploration generally, 29 per cent in favour and 44 per cent undecided.

There are now 130 opposition groups across the country and two-thirds of Sussex people want a moratorium, according to Geoffrey Lean in the Telegraph. New energy minister Matthew Hancock was unable to name a community that supported fracking when asked this morning.

Will that be a barrier to fracking? It will almost certainly slow down development – but ultimately economic and regulatory barriers will probably be more significant.

When would fracking start?

Getting an exploration licence is just the first step. The government has published a ‘ roadmap‘ of the multiple different permissions required before fracking can begin. Any one of these can be a stumbling block. This was demonstrated last week when West Sussex county council refused planning permission to shale firm Celtique Energie in a dispute over truck movements.

Can they frack under my living room?

Under current law drilling fracking wells under peoples’ homes constitutes trespass. This would not prevent fracking from taking place, but there would have to be a potentially lengthy legal process leading to relatively small amounts of compensation for landowners.

The government is consulting until 15 August on plans to change the law. This would speed up the process and would formalise a standard compensation package for communities affected by fracking.

Will shale gas bring down energy bills?

The short answer is no – according to the shale gas industry and most others. Costs to extract shale gas are expected to be much higher in the UK than in the US, where the industry has helped prices plummet. Even if the UK were to import US shale gas it might not bring down prices because of the costs associated with liquefying, transporting and regasifying it.

UK gas prices are set within a large European market so without a shale revolution across the continent it’s hard to see UK exploitation making much difference. Only a handful of fracking cheerleaders continue to insist shale gas will make energy cheap in the UK.

Is shale gas good for the climate?

Emissions from gas-fired electricity are half those from coal, leading some to argue it can be a clean ‘bridging fuel’ on the road to a low-carbon future. Others argue that, on the contrary, methane leaks during extraction make fracking dirtier than coal.

According to the Committee on Climate Change shale gas is better than coal as long as the leakage rate is below 11 per cent. We’ve taken a detailed look at the arguments over fugitive methane here.

But could a UK shale revolution bring down the country’s emissions overall? Not according to the government. The CCC says the UK power sector must be essentially decarbonised by 2030 so there’s a limited window in which to use gas without adding expensive carbon capture and storage.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concluded earlier this year that shale gas could play a role in the global decarbonisation effort – but only if it is carried out in a controlled way, used as a substitute for higher-emitting coal, and with emissions from the energy sector as a whole shrinking rapidly towards zero by mid-century.