Scientists around the world have been watching closely to see if an El Niño develops this year – a weather phenomenon in the Pacific that drives extreme weather worldwide.

After initially predicting with 90 per cent certainty we’d see an El Niño by the end of the year, forecasters began scaling back their predictions earlier this month.

But interest in the Pacific weather phenomenon shows no sign of waning. And after much talk of El Niño cooling off, there are hints it could be rebounding, say scientists.

El Niño watch

Every five years or so, a change in the winds causes a shift to warmer than normal ocean temperatures in the equatorial Pacific Ocean – a phenomena known as El Niño.

Together, El Niño and its cooler counterpart La Niña are known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Between them, they’re responsible for most of the fluctuations in global temperature and rainfall we see from one year to the next.

Earlier this year, the ocean looked to be primed for an El Niño, with above average temperatures in the eastern Pacific lasting throughout March and May.

But last month, forecasters across the world began dialling down their forecasts. The atmosphere had “largely failed to respond” to sea surface temperatures, scientists announced.

“Waiting for Godot”

This week, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) dropped the odds of an El Niño developing in autumn or winter to 65 per cent, down from 80 per cent earlier this month. As NOAA scientist, Michelle L’Heureux, described recently:

“Waiting for El Niño is starting to feel like Waiting for Godot”

NOAA says it still expects an El Niño to make an appearance in the next couple of months, and to last through early 2015.

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology (ABM) puts the chances of a 2014 El Niño a bit lower, at least 50 per cent – though that’s still double the normal chance of an event, it says.

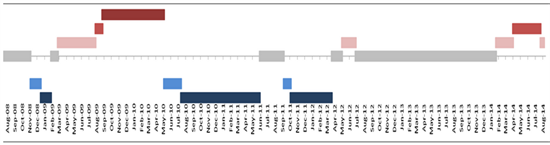

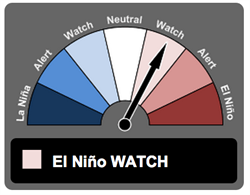

El Niño status is currently on WATCH level, meaning the chance of a 2014 event is at least 50 per cent (top). You can see how the status has changed since 2004 (bottom) Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology (ABM).

“Super” El Niño

In El Niño years, Indonesia and Australia see below average rainfall, while South America and parts of the United States see more than usual.

If an El Niño hits, it’s unlikely to be a strong one, forecasters are saying. But don’t rule out a “super” El Niño in 2014 just yet, warns climate scientist Agus Santoso in The Conversation:

“[A]re we right to dismiss the chances of a super El Niño this early in the season? We have been caught out before. The second-largest El Niño event on modern record, which hit in 1982/83, developed rather slowly before rapidly picking up in late August”.

And we don’t need a strong event to feel the impacts worldwide, adds Santoso:

“Even a moderate El Niño can significantly affect Australia’s rainfall.”

But conditions in the Pacific are changing all the time. The Australian Bureau of Meteorology suggests the Pacific is showing “some renewed signs of El Niño development”. It says :

“Some warming has occurred in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean in the recent fortnight, due to a weakening of the trade winds. If the trade winds remain weak, more warming towards El Niño thresholds is possible.”

As August draws to a close and September is shepherded in, the next few weeks will be very telling. The next update from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology is due on Tuesday.