Oxygen is an overlooked factor in past climate, study suggests

Robert McSweeney

06.11.15Robert McSweeney

11.06.2015 | 7:00pmIt’s well established how carbon dioxide, methane and water vapour affect our climate. But a new study suggests another gas may have played a role in Earth’s long climate history – oxygen.

Natural variations in atmospheric oxygen levels could be a missing factor in piecing together Earth’s past climate, the researchers say. The findings help explain why climate models tend to simulate temperatures 100m years ago that are lower than scientific evidence suggests.

Oxygen levels

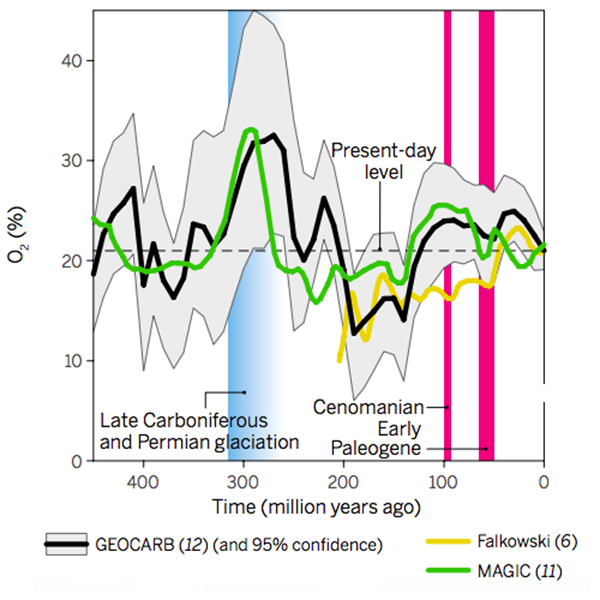

Today, oxygen makes up around 21% of the air we breathe. But that hasn’t always been the case. Over the last 500m years, known as the Phanerozoic eon, oxygen levels have been as low as 10% and as high as 35%.

This period has seen the evolution of life as we know it, and scientists know that changes in atmospheric oxygen has been intertwined with how life on Earth has thrived.

Now new research, published today in the journal Science, suggests that oxygen may have had a role in how our climate evolved as well.

Scattered sunlight

Oxygen levels have varied as the amount of vegetation covering the planet has changed, lead author Prof Chris Poulsen from the University of Michigan, tells Carbon Brief:

“Oxygen is produced as a waste product of photosynthesis. The production and burial of plant matter over long periods causes oxygen levels to rise. The decomposition of ancient organic matter on land uses oxygen, causing levels in the atmosphere to fall.”

But as all GCSE geography students will know, oxygen isn’t a greenhouse gas. So how could it have affected the Earth’s climate? Poulsen explains:

“Oxygen affects climate because it makes up a large fraction of the atmosphere’s mass. Reducing oxygen levels thins the atmosphere, allowing more sunlight to reach Earth’s surface.”

This extra sunlight causes more moisture to evaporate from the surface, increasing the amount of water vapour in the atmosphere. As water vapour is a greenhouse gas, this makes the Earth warmer.

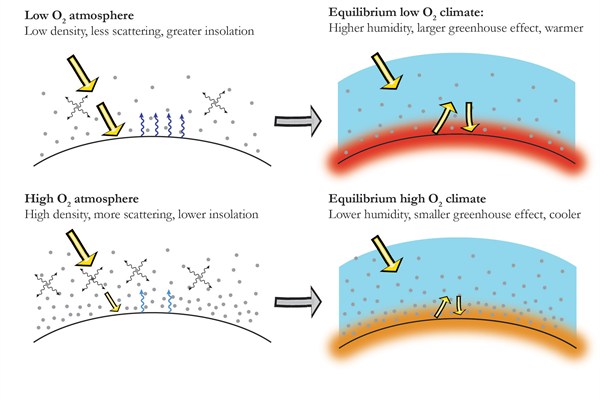

The figure below illustrates this effect: low oxygen levels are shown in the top images, and high levels in the bottom.

Schematic of the influence of oxygen levels on global climate. Credit: Chris Poulsen, University of Michigan.

Disappearing differences

To test their theory, the researchers ran a climate model to simulate conditions around 100m years ago – a time known as the Cenomanian age, during the Cretaceous period.

Climate models tend to simulate temperatures for this time that are lower than palaeoclimate records suggest, Poulsen says:

“Geological evidence indicates that the Cretaceous was a time of unusual warmth, especially at the poles. Paleoclimatologists have not been able to account for this warmth through the usual suspects of greenhouse gases, solar brightening, and continental drift.”

Scientists recreate past oxygen levels using a variety of methods, such as charcoal fossils and the chemical makeup of plant resins, says Poulsen. But none of these techniques are ‘bulletproof’ and different reconstructions often disagree, he says.

You can see three different records in the figure below, which comes from an accompanying Perspectives article that comments on the new paper.

Three long-term reconstructions of atmospheric oxygen. Peppe & Royer ( 2015)

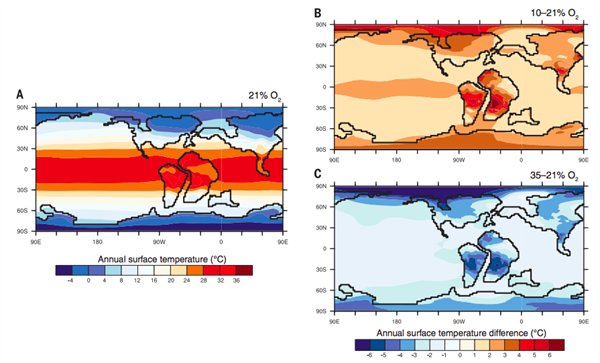

Poulsen and his colleagues ran the model for the range of possible oxygen levels during the whole Phanerozoic eon. You can see the results in the maps below.

Map A shows the simulated temperatures using present-day oxygen levels. Maps B and C show the difference when atmospheric oxygen is decreased and increased, respectively.

Simulated annual surface temperatures during the Cenomanian period for A) present-day oxygen levels, and the difference in simulated temperatures (from those in A) when using B) 10% oxygen level and C) 35% oxygen level. Source: Poulsen, C.J. et al. ( 2015)

The low oxygen model run gives the warm global temperatures that more closely resemble what the climate records show. With low oxygen, the differences between the model and the records ‘largely disappear’, say the authors of the Perspectives article.

The findings suggest scientists have been overlooking oxygen as a factor in unravelling climate, says Poulsen.

Very slow rate

If oxygen has played a role in our past climate, does that mean it could be having an impact today? Definitely not, says Poulsen:

“Oxygen levels are dropping today but at a very slow rate – approximately tens of parts per million per year. This rate is much too slow to affect climate in the modern world.”

The only way oxygen levels could have a noticeable impact on our climate is if the slow decline in oxygen continued for another million years, Poulsen adds.

But although their theory needs validating using other climate models, the research could help with piecing together the Earth’s climatic history, he says.

This new research provides a compelling reason to develop a robust history of atmospheric oxygen for the last 500m years, says the Perspectives article. Doing so could means it’s time to consign these disagreements to history.

Main image: High altitude view of the Earth in space over the desert in the western United States.

Poulsen, C.J. et al. (2015) Long-term climate forcing by atmospheric oxygen concentrations, Science, doi:10.1126/science.1260670 & Peppe, D.J. and Royer, D.L. (2015) Can climate feel the pressure? Science, doi:10.1126/science.aac5264