Roz Pidcock

02.07.2014 | 6:15pmThere’s a heated academic tussle going on over climate predictions. A high profile group of scientists has criticised the results of a paper published in Nature last year, which made some very precise forecasts for when different parts of the planet would feel the effects of climate change.

Last year’s paper predicted to within a year or two when different regions would consistently see temperatures exceeding the bounds of natural variability. Writing in Nature today, the paper’s critics say that’s a level of confidence that can’t be supported by our current understanding of climate science.

What may sound like a fairly technical dispute raises some tricky questions about the limits of science, and the way journals choose what to publish.

“Unprecedented” climate change

In October last year a Nature paper got quite a bit of attention from the media with some bold statements about when different regions of the world can expect to enter the realms of “unprecedented” climate change. We covered it, here.

Reuters talked about a “shift to a new climate”, while the Daily Mail opted for the punchier ”Apocalypse Now: Unstoppable man-made climate change will become reality by the end of the decade’.

In the paper, Professor Camilo Mora and colleagues from the Universities of Hawaii and the Ryukyuk in Japan pinpointed when average temperatures in different parts of the world would consistently stay above the bounds of natural variability experienced since 1860.

Today a group of high profile scientists have published a letter in Nature disputing some of the findings. In particular, they say the research suggests “too much certainty”.

A question of timing

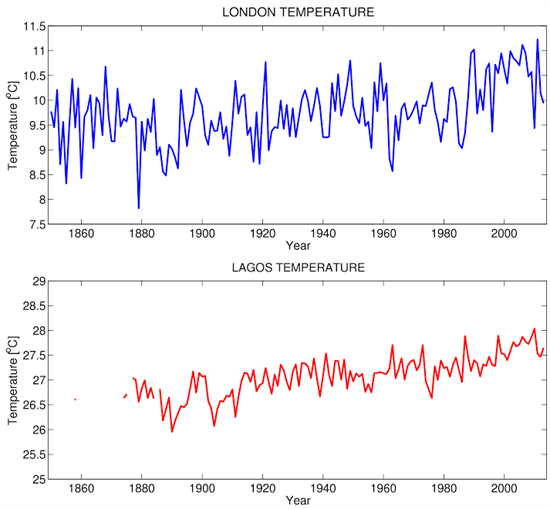

The Hawkins paper agrees withe Mora et al. on their underlying conclusion that the tropics will see temperatures emerge from natural variability earlier than anywhere else in the world. That’s because the ups and downs of natural variability are smaller than in other parts of the world, as the graph below shows.

The temperature signal is easier to spot in the tropics, such as in Lagos (bottom panel, red) because the range of natural variability is small. In higher latitudes such as London (top panel, blue) natural variability is more pronounced, masking the signal of greenhouse warming for longer. Source: Hawkins et al. ( 2014)

But the precision with which Mora et al. predict when places will emerge from historical variability is unwarranted and misleading, say the scientists who authored today’s letter. Dr Ed Hawkins from Reading University tells us:

“Mora et al. claim that they can say precisely when the “point of emergence” will occur, to within a couple of years in many tropical regions. [We], along with many other papers in the scientific literature, provide ample evidence that this precision is not justified”.

We spoke with Hawkins, who explains in the video below why it’s difficult to know precisely when the “signal” of greenhouse gas warming will rise above the “noise” of natural variation.

Expressing uncertainty

Hawkins and his team says the Mora study doesn’t give a realistic idea of what the level of uncertainty is in its predictions.

Take the city of Lagos, for example. Mora et al. predicted the city would begin experiencing an “unprecedented” climate in 2043, give or take two years either side.

Using a method that the authors say better captures real-world variability, the Hawkins letter says that point is likely to occur between 2024 and 2052 but that they can’t be more precise than that 28 year window.

The mid point of that range – 2038 – is not far off the Mora prediction of 2043. The difference between the two studies is that while Mora et al. offer their mid point as a “best estimate”, Hawkins et al. consider the full range of possibilities the models come up with. This approach suggests there’s a more than 85 per cent change the actual year will lie outside the narrow range of uncertainty Mora gives alongside the central estimate, Hawkins tells us.

This might seem like a fairly esoteric dispute. But it matters, the researchers say, because overstating the certainty with which scientists can make predictions risks losing public trust if they turn out to be wrong.

What’s more, being overconfident about precisely when something will happen could also lead to problems when it comes to making adaptation decisions.

Right to reply

It’s not unusual for a journal to publish a comment by one group of scientists criticising another group. Usually, the journal will also give the authors of the original paper a chance to respond.

So this week’s edition of Nature also carries a response from Mora et al, who defend their work against the criticisms from Hawkins’s team, saying:

“We contest their assertions and maintain that our findings … remain unaltered in light of their analysis”.

Of course, it isn’t abnormal for scientists to disagree. As Reading University’s professor Rowan Sutton, a co-author on the Hawkins paper, explains in the video clip below, it’s a fairly normal way that scientific understanding advances.

An independent judge

But on this occasion, Nature has decided to take the unusual step of including an article by an independent climate scientist – who was not involved in either piece of research – to discuss the disagreement between author teams. We understand this is the first time the journal has done this for such an exchange.

The author of this “News and Views” article, professor Scott Power, from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, concludes that in his opinion the approach taken by Hawkins gives a “more realistic estimate of the range â?¦ that could occur in the real world”.

We asked Mora about the difference between his and Hawkins’s approaches to expressing uncertainty. He told us both are valid, but that research by other scientists suggests his is the most appropriate to use in this case. In the Nature comment, Mora and colleagues cite a paper by Dr Claudia Tebaldi and Professor Reto Knutti in support of this point.

However, Tebaldi told us today she thought her work had been taken “absurdly out of context”. In a letter to the Nature editor, seen by us but as yet unpublished, Tebaldi says:

“I would like to call your attention to an egregious case of “citation out of context” appearing in the comment/rebut by Mora et al. today on your journal website. Their use of Tebaldi and Knutti (2007) to support their projections … is laughable, since our paper actually presents arguments against it”.

It is, in short, a right old scientific ding dong.

On reflection

We asked Nature for a comment on whether, on reflection, it felt it was right that the original paper by Mora last year was published. We also asked why the journal had taken the unusual step of asking for an independent climate scientist to weigh in on the dispute this time around. A spokesperson for Nature told us:

“Nature considers that its responsibility is to reflect the perspectives of the research community and, as such, published both the Brief Communications Arising and the News & Views article … For confidentiality reasons, we cannot discuss the specifics of the review process or history of any Nature paper with anyone other than the authors.”

Nevertheless, the steps the journal has taken show how sensitive such disagreements are.

This exchange of views may seem esoteric, but the question of just how precise scientific predictions about the future can be is one which cuts to the heart of a lot of climate science and policy discussions.

With the authors of today’s letter arguing that oversimplifying complicated climate science does no one any favours, this probably isn’t the last we’ll hear on this issue.