Only three years to save 1.5C climate target, says UNEP

Simon Evans

11.03.16Simon Evans

03.11.2016 | 11:00amThe door will close on the 1.5C warming limit unless countries raise their ambition before 2020, says the UN Environment Program (UNEP).

Greater pre-2020 action is the “last chance” for 1.5C, says the latest annual UNEP Emissions Gap report. It is published one day before the Paris Agreement on climate change enters into force. The deal pledges to keep warming “well below” 2C and to make efforts to keep it below 1.5C.

This year’s report is the first to explicitly measure the so-called “ambition gap” for 1.5C and its call to action is more strongly worded than previous reports. However, its key messages are unchanged. Carbon Brief puts the 2016 emissions gap report in context.

Emissions gap

Each year since 2010, UNEP has measured current climate ambition against the latest understanding of what will be necessary to avoid dangerous warming. Any shortfall is known as the “emissions gap”.

Its starting point is the allowable level of global greenhouse gas emissions at a fixed point in future, for a likely chance of limiting warming to a given temperature. In its earliest reports, the reference points were allowable emissions in 2020 and a warming limit of 2C.

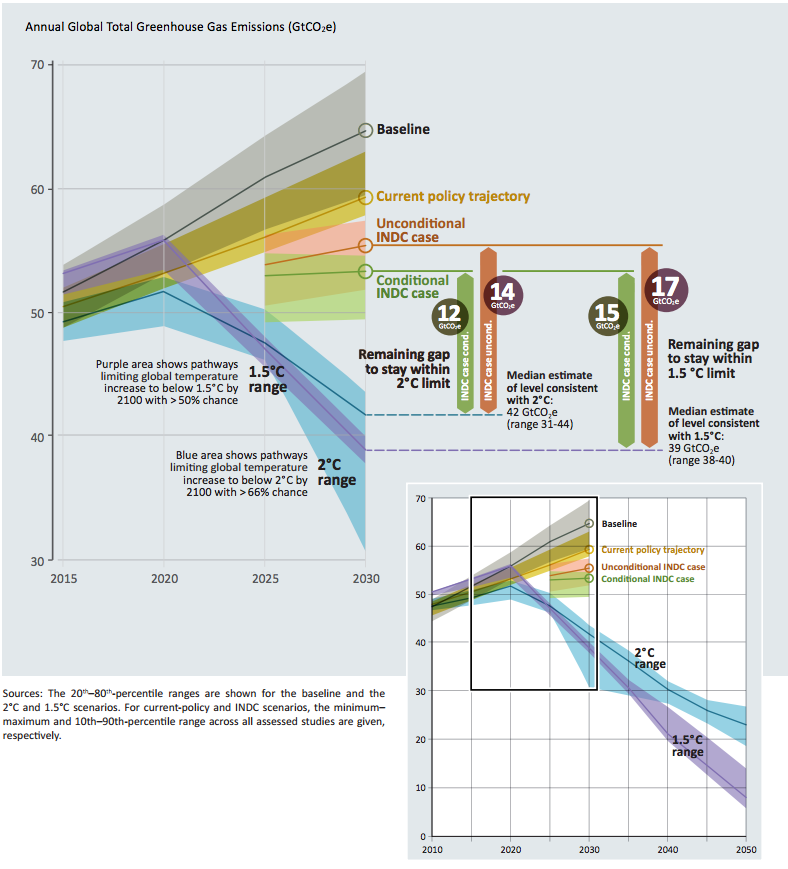

This year, in line with the ambition of the Paris Agreement, UNEP has extended its analysis to allowable emissions in 2030, for warming limits of either 1.5 or 2C.

Against these limits, emissions have actually been increasing. They reached around 53 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e) in 2014, UNEP says.

For a 50% chance of limiting warming to 1.5C, this total should be no more than 39GtCO2e in 2030. For a likely chance (66%) of 2C, the limit is 42GtCO2e. (Note the different probabilities here. Scenarios with a likely chance of avoiding 1.5C are even more challenging).

Current plans fall well short of these goals, UNEP says. If countries carry out their climate pledges, emissions would remain at 53-55GtCO2e in 2030, it finds. This would leave an emissions gap of 12-14GtCO2e for the 2C limit, or 15-17GtCO2e for the 1.5C limit.

Global greenhouse gas emissions under different scenarios and the emissions gap in 2030. INDCs are intended nationally determined contributions submitted by countries ahead of Paris. Some INDCs are conditional on receiving financial support. Source: UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2016.

Put another way, countries’ climate pledges amount to less than half of the cuts needed to reach the goals they agreed in Paris. What’s more, there is very little time to close this gap.

The Paris deal has a built-in ratchet mechanism, designed to raise ambition over time. The first formal opportunity to use this is in 2018. However, UNEP says that raising ambition before 2020 “is likely the last chance to keep the option of limiting global warming to 1.5C”, leaving just three full years.

Wakeup call

In a foreword to this year’s report, Erik Solheim, head of UNEP, and Jacqueline McGlade, UNEP’s chief scientist, write:

“We must take urgent action. If we don’t, we will mourn the loss of biodiversity and natural resources. We will regret the economic fallout. Most of all, we will grieve over the avoidable human tragedy; the growing numbers of climate refugees hit by hunger, poverty, illness and conflict will be a constant reminder of our failure to deliver…As the Paris Agreement legally enters into force, we sincerely hope this report will be a wakeup call to the world.”

These words are by far the most dramatic to introduce a UNEP emissions gap report. The report also contains words of caution on negative emissions, which are included in “most scenarios” for 1.5 or 2C.

The report describes options for negative emissions, from afforestation and soil carbon restoration through to biomass with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). However, it notes “important challenges” to their widespread use, including high land use and competition with biodiversity.

Check out Carbon Brief’s archive to learn more about the political, technical and environmental constraints at play. In short, relying on negative emissions is risky, since they are not sure to work.

On the other hand, “hedging against a strong reliance on negative emissions…is only possible by reducing emissions more steeply in the very near term [5 to 15 years],” the report says.

This echoes the findings of a recent commentary in the journal Science, which said mitigation “should proceed on the premise that [negative emissions] will not work at scale”.

Taken together with the timeline for saving the 1.5C warming limit, the clear message of the UNEP emissions gap report is that only urgent, stringent cuts to greenhouse gas output will be consistent with maintaining a decent chance of avoiding dangerous climate change.

Gap years

How does this message compare to earlier UNEP reports? The first emissions gap report was published in 2010. At the time, it said not a single published scenario was consistent with a likely chance of limiting warming to 1.5C. It identified an emissions gap for 2C of 5-9GtCO2e in 2020.

Introducing the report, Achim Steiner, then executive director of UNEP, wrote that “tackling climate change is still manageable”. Still, the 2010 report noted that “pathways capable of meeting the 2C and 1.5C limits” would require the development of “technologies for achieving negative emissions”.

In a box explaining the concept of negative emissions, it said:

A year later, the 2011 emissions gap report was still unable to identify any published pathways to 1.5C, with at least a likely chance of success. It said the 2020 emissions gap for 2C was larger than thought a year previously, at 6-11GtCO2e.

Introducing the report, Steiner wrote in more urgent terms:

It once again pointed to negative emissions and BECCS, saying that 2C pathways “have a peak [in emissions] before 2020…and/or reach negative emissions in the longer term”.

Urgent action

The 2012 edition, produced with support from the UK government, said the 2020 emissions gap for 2C was even larger than thought, increasing it to 8-13GtCO2e. It also looked further out to 2030, saying emissions that year should be a “maximum” of 37GtCO2e to remain 2C compatible.

In contrast to the 2010 and 2011 editions, the report said 1.5C pathways had been identified. It said: “The few studies available indicate that a 1.5C target can still be met”. It said emissions in 2020 would have to be no more than 43GtCO2e and be followed by “very rapid” reductions.

Steiner wrote in the foreword:

It said that “the majority” of scenarios compatible with a likely chance of avoiding 2C relied on negative emissions later this century. It added: “negative emissions is simple in analytical models but in real life implies the need to apply new and often unproven technologies.”

By 2013, the emissions gap report was receiving support from the German government. It was introduced by Steiner as “a call for political action”. It left the 2C emissions gap for 2020 broadly unchanged at 8-12GtCO2e and repeated the need to keep emissions in 2030 to 35GtCO2e.

It said:

More negative

The 2014 edition outwardly continued in a similar vein, with Steiner writing that “consistent and decisive action is required without any further delay”. However, it also introduced significant changes to the underlying scenario analysis.

For instance, it increased allowable emissions in 2030 from 35GtCO2e to 42GtCO2e. It justified this change on the basis that previous analysis had assumed stringent efforts to reduce emissions starting in 2010. These efforts had failed to materialise.

In order to balance out this increase in 2030 emissions while maintaining a 2C pathway, the 2014 report scenarios “assume that a much higher level of negative emissions will be needed”.

Despite these changes, to allow higher emissions in the medium term, UNEP still identified large emissions gaps of 8-10GtCO2e in 2020 and 14-17GtCO2e in 2030.

The 2015 report, published in the run-up to the COP21 Paris climate talks, maintained the 42GtCO2e limit for 2030. However, it reduced the emissions gap for that year slightly, to 12-14GtCO2e, as a result of the climate pledges made in advance of Paris.

It reiterated that 2C pathways are reliant on negative emissions later this century. Introducing the findings, Steiner concluded optimistically: