Finland has a 15-year-old problem called Olkiluoto 3. This nuclear plant was once the bright star of Finland’s energy future and Europe’s nuclear renaissance.

It was seen as a key component in Finland’s plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2050 and end reliance on foreign imports of electricity, even during its long, dark Arctic winters. It is supposed to provide Finland with a low-carbon source of electricity for at least 60 years.

A 2006 article in the Telegraph spoke of the rebirth of Finnish love for nuclear power, describing the Olkiluoto site in phrases that could have been lifted from a pastoral poem: a “Baltic island of foraging swans”, “pine-scented” air and “unusually large salmon”.

But this source of hope has turned sour. Olkiluoto 3 — almost unpronounceable to non-Finns — is now nine years behind schedule and three times over budget.

It has been subject to lawsuits, technology failure, construction errors and miscommunication. A rift between the companies behind the plant has been described as “one of the biggest conflicts in the history of the construction sector”.

At best, it has been a turbulent lift-off to the lauded rebirth of nuclear power in western Europe. For the UK, which hopes to be a part of this renaissance, the story of Olkiluoto 3 offers a cautionary tale.

Background

The story of Olkiluoto 3 began in 2000, when Finnish utilities company TVO first applied to build a new nuclear power unit, in an attempt to wean the country off foreign imports of electricity and supply a new source of low-carbon energy.

In 2002, Finland’s parliament granted its permission, voting 107-92 in favour of the new unit. And in December 2003, Finland became the first country in Western Europe to order a new nuclear reactor in 15 years.

This was welcome news to nuclear supporters. Nuclear power stagnated in the 1990s, with accidents in Three Mile Island and Chernobyl in the ’70s and ’80s creating jitters about the risks of the industry, while the economic costs of building plants created nervousness among investors in newly liberalised energy markets. Olkiluoto 3 was seen as the sign that European nuclear was set for a revival.

With its new-and-improved Generation III+ technology, Olkiluoto 3 was meant to be safer and more efficient, as well as cheaper and faster to build than its predecessors — an ageing European fleet of Generation II plants built in the 1970s and 80s.

The 2014 World Nuclear Industry Status report points out that the former enthusiasm surrounding Generation III reactors has “dissolved”. Some proponents of nuclear power have argued that even these supposedly new-and-improved plants ought to be put aside for an even more modern round of Generation IV plants — technology that is still being developed, with China currently planning the world’s first in the province of Jiangxi.

It was decided that Olkiluoto Island in western Finland would host the new plant, where the Gulf of Bothnia could cool the steam used to turn the turbines and generate electricity. It would sit alongside two of Finland’s four existing nuclear plants (intuitively called Olkiluoto 1 and 2).

Olkiluoto 3 would use a new type of technology called a European Pressurised Reactor (EPR), which France has also since adopted for a new nuclear plant. China is building two EPRs, as well.

The plan was that Olkiluoto 3 should have a capacity of 1,600 megawatts. It would cost €3bn and come online in 2009.

Animation illustrating the operating principles of nuclear power plant units. Credit: TVO.Construction problems

It is now 2015, and Finland still does not have its new nuclear plant.

The companies behind the project are at loggerheads. TVO is seeking compensation from Areva in court, the company responsible for supplying the reactor and turbine, and Areva is pursuing a counterclaim.

Herkko Plit, the deputy director of Finland’s energy department, tells Carbon Brief:

Construction started in August 2005. The problems started early, with the incorrect laying of the concrete base slab — a structure that is supposed to be able to withstand the weight of the entire power plant collapsing on it.

This was accompanied by errors in the manufacture of the steel liner — the part of the unit that is responsible for preventing the release of radioactive materials into the environment, and is supposed to be able to withstand forces such as an aeroplane crash.

In 2006, the Finnish Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority (STUK) conducted an investigation into the construction of the plant, following concerns about its safety culture.

The resulting report gives a variety of reasons for the problems encountered. Top of that hefty list comes problems with subcontractors responsible for carrying out much of the manufacturing work.

Many of the organisations chosen to work on the different parts of the plant did not have any experience in nuclear, and little understanding of the safety requirements.

One of the people interviewed for that report said that, “as safety culture is a concept usually associated with plants that are in operation, it has been difficult for them to understand what it could mean at the construction stage”.

While such issues had not compromised the safety of the plant, the report concluded that they were responsible for some of the first delays to the plant.

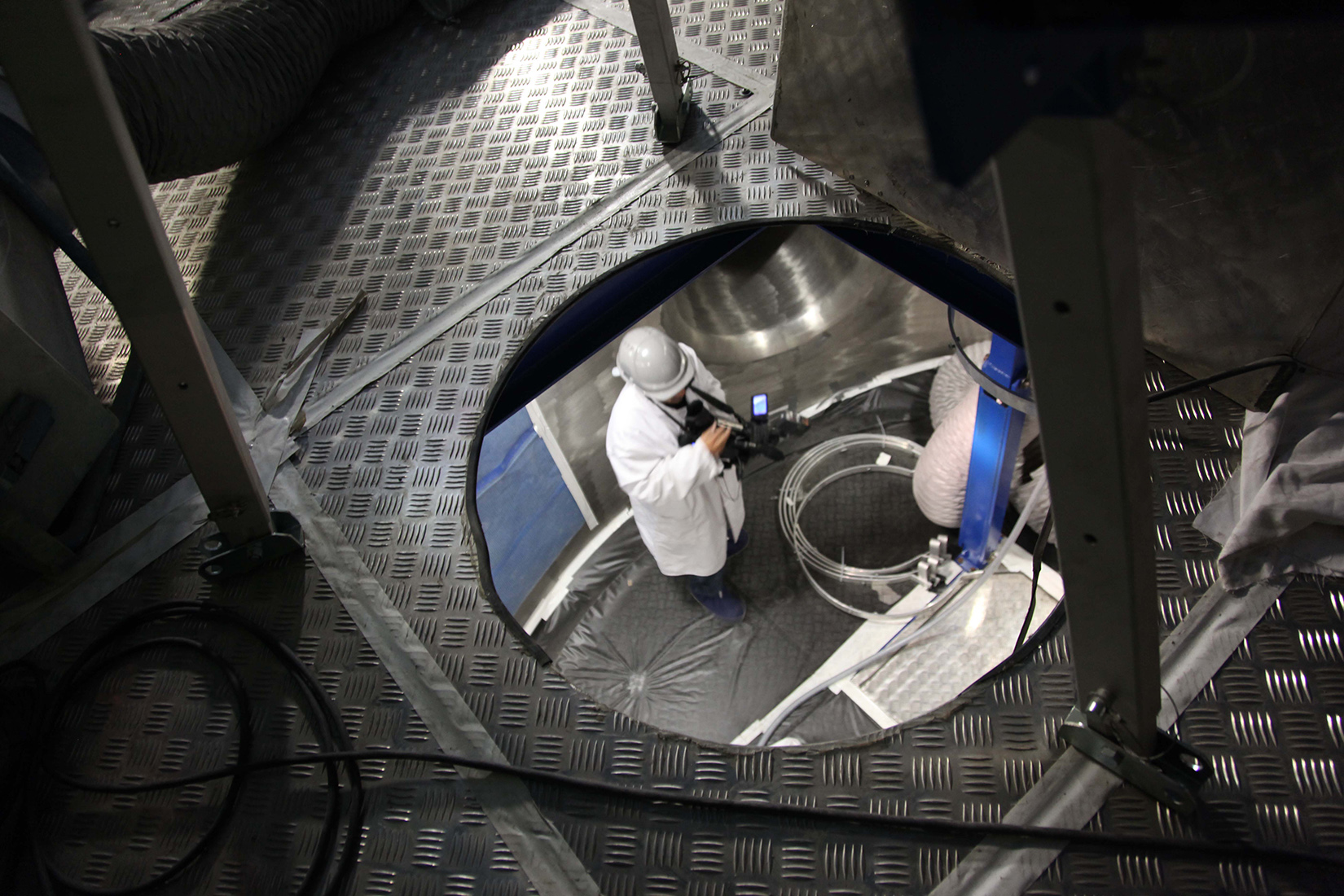

The 1600 MW atomic reactor is being made by French company Areva and will cost over €5 billion. This third generation nuclear reactor can withstand a direct hit by Boeing jetliner and is considered the safest plant in the world. © Pallava Bagla/Corbis.

“The nervous system”

Later came problems with the instrumentation and control system, which is for monitoring and control. The International Atomic Energy Agency describes it as “the nervous system” of the plant.

This was finally approved in 2014, after four years of “exchanges” with TVO, as Areva put it. In August 2015, these cabinets were finally delivered to the site. Pasi Tuohimaa, TVO’s head of communications, tells Carbon Brief:

The good news precipitated a rare moment of harmony in the bitter feud between Areva and TVO. The rivals held their first joint press conference to mark the occasion. “It’s such a big milestone for both of us,” TVO’s Tuohimaa adds.

Who will suffer?

TVO signed a contract with Areva for the plant — a one-off payment of €3.2bn, covering the EPR and other costs. Such contracts are rare in nuclear power plants, due to the construction risks associated with the technology.

At the time, it was seen as an expression of confidence in the industry. For Areva, the opportunity to build an EPR in Finland offered a chance to show that nuclear could survive and become competitive in the liberalised Scandinavian energy market — a boost for the company, which has not managed to sell a reactor since 2007.

The turnkey contract meant spiralling costs of the Olkiluoto 3 plant have fallen at Areva’s door. This has been the subject of a bitter dispute between TVO and Areva.

Areva maintains that TVO’s “inappropriate behaviour” has been responsible for the delays, and that the utility company should, therefore, be liable for the multi-billion euro cost overruns. Meanwhile, TVO says Areva is responsible for failing to build the plant according to schedule. It has called the delays “hard to accept”.

The compensation claims, as well as the costs of the plant itself, keep spiralling upwards. In August 2015, TVO raised its claim against Areva to €2.6bn from its previous €2.3bn, and €1.8bn before that. In October 2014, Areva raised its own claim against TVO to €3.5bn from €2.6bn. The case is being dealt with in the International Chamber of Commerce‘s arbitration court.

Nonetheless, Areva has been forced to accept losses. The company, which hasn’t turned a profit since 2010, recorded net losses of €4.8bn in 2014, largely due to Olkiluoto. It has agreed to sell a majority stake in its nuclear reactor business to EDF.

If the lawsuit turns against TVO, it could be Finland’s industry that feels the pain. The utilities company is owned by shareholders that buy the right to use the electricity produced by the power station.

Its majority shareholder, for instance, is Pohjolan Voima Oy — a Finnish energy company that provides power to its shareholders, including two pulp and paper manufacturers, which pay for the production cost of the electricity.

Such industries could buckle under the inflated costs of electricity, which could end up more expensive than the electricity bought from the joint Nordic “pool”, says Stephen Thomas, professor of energy policy at the University of Greenwich. He tells Carbon Brief:

The giant copper and bentonite casks in which Finland proposes to bury its nuclear waste in a geological depository. © Pallava Bagla/Shutterstock.

Future of Finnish nuclear

Despite the trials and tribulations of Olkiluoto 3, Finland does not seem to have been swerved from its nuclear path.

Another nuclear power plant is planned for the north of Finland. Hanhikivi 1 will be the first nuclear power plant from another power consortium Fennovoima, and is due to come online in 2024.

The project is already facing controversy. Its reliance on Russian investment at a time when other countries have sought to isolate Moscow due to its invasion of Ukraine has raised eyebrows, while a Croatian investor was rejected by the government in Helsinki following suspicions that it was also being controlled from within Russia.

Construction work has also begun on a megaproject to store nuclear waste. Onkalo, which translates as “cavity”, is an underground tunnel built 520m into the Finnish bedrock. A project of Posiva, a company jointly owned by TVO and Fortum, it is located at the site of Olkiluoto.

Onkalo is designed to protect nuclear waste for 100,000 years. The timespan, almost impossible to conceptualise, caught the imagination of Danish director Michael Madsen, who made a documentary about the project, and the difficulty of communicating danger millennia down the line.

The possibility of a fourth reactor at the Olkiluoto site proved to be one too many, however. For now, TVO has given up on plans on Olkiluoto 4.

Plit, from Finland’s energy department, remains cheerful in the face of 15 years of difficulties and delays. He tells Carbon Brief:

Prof Thomas at University of Greenwich is not so sure that the loss of knowledge since the last burst of nuclear construction can be entirely blamed. He points out that none of the four EPRs under construction have gone to plan so far, so to say that Olkiluoto is suffering only because of its novelty is oversimplistic. He tells Carbon Brief:

A cautionary tale

Some are already seeing Finland’s troubled relationship with new nuclear as a cautionary tale for the current UK government, which hopes to oversee its own nuclear renaissance.

The energy company EDF plans to build two new reactors at Hinkley Point. These will be the same design as Olkiluoto 3 — Areva’s EPR. The project will cost £24.5bn, and has already been subject to numerous delays.

The government has shown itself to be a devoted fan of the project, most recently offering a £2bn guarantee to smooth along the path to construction.

Despite this, it has been difficult to secure investors, who continue to be spooked by the ghosts of Flamanville in France and Olkiluoto, admitted the chief executive of EDF recently. Jean-Bernard Levy told French Financial daily Les Echos that, for those who have witnessed the spiralling costs and delays to date, it is “difficult to commit”.

The UK government hopes to confirm Chinese funding during a state visit by President Xi Jinping this week, which would prove instrumental in making the project happen.

EDF has insisted that it has learnt from the past, but Prof Thomas at the University of Greenwich is not so sure. The EPR is a “lousy design” that has not only tripped up the Finns, but also the French and Chinese. He tells Carbon Brief:

Main image:Nuclear power station being built at Oikiluoto in southern Finland.

-

New nuclear: Finland's cautionary tale for the UK

-

Finland's much-delayed and over-budget nuclear power station