Negative emissions have ‘limited potential’ to help meet climate goals

Daisy Dunne

01.31.18Daisy Dunne

31.01.2018 | 11:01pmThe potential for using negative emissions technologies to help meet the goals of the Paris Agreement could be more “limited” than previously thought, concludes a new report by European science advisors.

Negative emissions technologies (NETs) describe a variety of methods – many of which are yet to be developed – that aim to limit climate change by removing CO2 from the air.

Some of these techniques are already included by scientists in modelled “pathways” showing how global warming can be limited to between 1.5C and 2C above pre-industrial levels, which is the goal of the Paris Agreement.

However, the new report says there is no “silver bullet technology” that can be used to solve the problem of climate change, scientists said at a press briefing held in London.

Instead, “the primary focus must be on mitigation, on reducing emissions of greenhouse gases,” they added.

Zero emissions

The 37-page report was produced by the European Academies Science Advisory Council (EASAC), an independent group made up of staff from the national science academies of EU member states, Norway and Switzerland, which offers scientific advice to EU policymakers.

Drawing on the results of recently published research papers, the report assesses the feasibility and possible impacts of NETs.

The report splits these “technologies” into six categories:

- Afforestation and reforestation

- Land management to increase soil carbon

- Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS)

- Enhanced weathering

- Direct capture of CO2

- Ocean fertilisation.

A Carbon Brief article published in 2016 explained how these proposed technologies might work.

Though differing in approach, all of the proposed NETs aim to slow climate change by removing CO2 from the atmosphere and storing it underground or in the sea.

Some scientists argue that such technologies could be used to soak up some of the CO2 that is released by human activity, which could, in turn, help the world to achieve “net-zero” greenhouse gas emissions.

Net-zero emissions is a term used to describe a scenario where the amount of greenhouse gases released by humans is balanced by the amount absorbed from the atmosphere.

Achieving net-zero emissions within this century will be key to limiting global warming to between 1.5C and 2C above pre-industrial levels, says Prof Michael Norton, EASAC environment programme director and member of the expert group behind the report. At a press briefing, he said:

“Indeed, without assuming that technologies can remove CO2 on a large, that’s gigatonne [billion tonne] scale, IPCC scenarios have great difficulty in envisaging an emission reduction pathway consistent with the Paris targets.”

However, the new report suggests that there is currently no “silver bullet” technology that can absolve the world of its greenhouse gas emissions, scientists said at a press briefing. The report concludes:

“We conclude that these technologies offer only limited realistic potential to remove carbon from the atmosphere and not at the scale envisaged in some climate scenarios.”

The report also shows that many of the NETs could have large environmental impacts, says Prof John Shepherd FRS, emeritus professor of ocean and Earth sciences at the University of Southampton and member of the expert group behind the report. He told the press briefing:

“Some of these techniques would have adverse environmental impacts, including some of the ones that appear to be natural. There is an emotional response in most people to prefer natural appearing solutions, but, in many cases, the environmental are as great as the more engineering-type applications.”

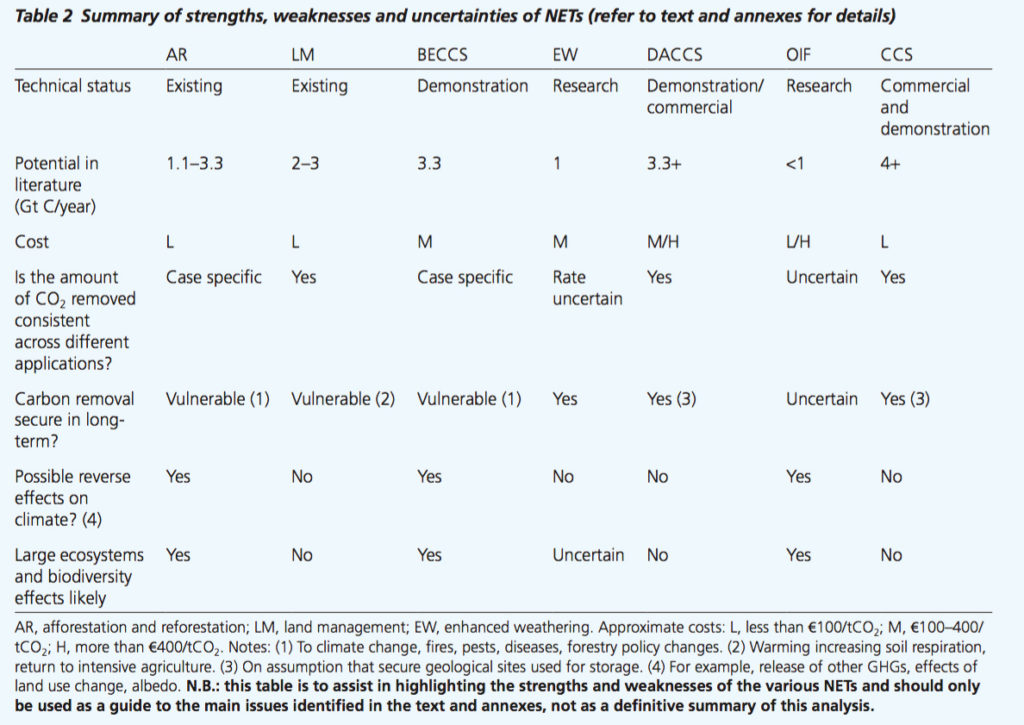

The “pros and cons” of each proposed technology are summed up on the table below. The top half of the table includes: the technical status of each technology; the amount of carbon that could be removed if the technology were to be implemented on a wide scale; the potential cost of implementing the technology (low/medium/high); and the likely efficacy of each method.

The bottom half of the table assesses: the relative security of the carbon storage of each technology; the possibility that the technology may actually contribute to climate change; and the possibility that the technology could have environmental impacts.

A summary of the strengths, weaknesses and uncertainties of negative emissions technologies (NETs). Technologies include afforestation and reforestation (AR), land management (LM), bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), enhanced weathering (EW), direct air capture and storage (DACCS), ocean fertilisation (OIF) and carbon capture and storage (CCS). Source: EASAC (2018)

Blow for BECCS?

One of the techniques under scrutiny in the new report is BECCS. Put simply, BECCS involves burning biomass – such as trees and crops – to generate energy and then capturing the resulting CO2 emissions before they are released into the air.

BECCS has been labelled one of the “most promising” NETs and is already included by scientists in many of the modelled “pathways” showing how global warming can be limited to 2C above pre-industrial levels.

However, BECCS has yet to be demonstrated on a commercial basis, the report finds, and its ability to effectively store large amounts of carbon is still “uncertain”.

Recent research has revealed a number of “drawbacks” to using BECCS on a wide scale, Norton said:

“These include the reality that even if all the carbon emitted when the biomass is burnt were to be captured, extensive emissions across the supply chain will not be captured, thus severely limiting its effectiveness as a negative carbon technology.”

In other words, the emissions resulting from the different stages of BECCS, including on transportation and on applying nitrogen fertilisers, may significantly reduce the technology’s overall ability to reduce the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. In some cases, biomass energy might have higher emissions than fossil fuels.

On top of this, implementing BECCS on a large scale would require large amounts of land to be converted to biomass plantations, which could have considerable environmental impacts, the report notes. Carbon Brief recently covered new research investigating how using BECCS could affect different aspects of the natural world.

Forest fall out

- Explainer: 10 ways ‘negative emissions’ could slow climate change

- In-depth: Experts assess the feasibility of ‘negative emissions’

- Timeline: How BECCS became climate change’s ‘saviour’ technology

- Guest post: Do we need BECCS to avoid dangerous climate change?

- Analysis: Is the UK relying on ‘negative emissions’ to meet its climate targets?

The report also assesses the potential of afforestation, creating new forests on land that was not previously forest, and reforestation, planting new trees on land that was once forest, to remove carbon from the atmosphere.

Trees absorb carbon from the atmosphere during photosynthesis and then use it to build new leaves, shoots and roots. By doing this, trees are able to store carbon for long periods.

However, implementing afforestation on a large scale could have “significant” environmental impacts, the new report finds. This is because growing new forests would require a large amount of land-use change and the application of nitrogen fertilisers. The production of nitrogen fertilisers releases a group of potent greenhouse gases known as nitrous oxides, along with CO2.

On top of this, new trees take many years to grow and so will not be able to immediately absorb large amounts of carbon from the atmosphere, Norton said:

“We can also see many scenarios in which the land-use change involved in extending forestry would be counterproductive for decades or even centuries.”

Norton said that curbing the rate of deforestation, which is causing the release of large stores of carbon from the world’s tropical regions, should be a priority for policymakers. He added:

Forestation and reforestation offer simple ways of increasing carbon stocks, but it would be a mistake to be distracted from the reality of the current situation which is that…carbon is being lost by continuing deforestation.

Cutting to the chase

Despite potential drawbacks, there may be some scenarios where the use of NETs will be “necessary” to balance the release of greenhouse gases, said Shepherd:

“They are especially likely to be necessary to deal with intractable sources of greenhouse gases, in particular aviation and agriculture.”

In other words, NETs may be needed to compensate for industries that are unable to radically cut their rate of greenhouse gas emissions.

Such industries could include cattle ranching and rice production, says Dr Phil Williamson, associate fellow at the University of East Anglia, who was not an author of the new report. At the sidelines of the press briefing, he told Carbon Brief:

“There’s a whole lot of things that are going to be very difficult to control, including methane from cattle and methane from rice. We’re not going to stop growing rice, so we’re still going to have methane emissions. In order to have that balance, we’re still going to need some negative emissions technologies.”

However, the “primary focus” of policymakers should be on rapidly cutting greenhouse gas emissions, said Prof Gideon Henderson FRS, professor of Earth sciences at the University of Oxford and reviewer of the report. He told the press briefing:

“The primary focus must be on mitigation, on reducing emissions of greenhouse gases. That’s not going to be easy, but it’s undoubtedly going to be easier than doing NETs at a substantial scale.”