Nature-based solutions: How can they work for climate, biodiversity and people?

Multiple Authors

07.11.22Multiple Authors

11.07.2022 | 4:01pmExperts gathered in Oxford this month to discuss how “nature-based solutions” can be used to tackle the twin threats of climate change and biodiversity loss.

Over three days at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, the Nature-based Solutions Conference considered techniques such as forest creation or mangrove restoration, which are increasingly appearing in climate strategies.

In theory, such projects could also help to reverse the loss of wildlife, provide economic boosts to local communities and strengthen resilience against climate impacts.

But the topic can be highly contentious and the conference provided a space for critics to outline their objections to nature-based solutions. Speakers took aim at companies and governments “greenwashing” and treating the natural world as a commodity.

In her opening address, conference organiser and founder of the Nature-based Solutions Initiative at the University of Oxford, Prof Nathalie Seddon, posed the central question of the event:

“How do we ensure that nature-based solutions support thriving human societies and ecosystems without compromising efforts to keep fossil fuels in the ground?”

Carbon Brief was at the conference, and in this piece draws together some of the key themes that emerged from the scientists, Indigenous representatives, policy experts and activists who spoke there.

- What are nature-based solutions?

- What are the biggest concerns around nature-based solutions?

- How can they be scaled up effectively and fairly?

- Who should pay for nature-based solutions?

- What is the role of Indigenous and local communities?

- How can nature-based solutions avoid ‘greenwashing’?

- Can nature-based solutions be effectively implemented?

- What is the role of nature-based solutions in international negotiations

What are nature-based solutions?

When they began planning the conference two years ago, Seddon said her team had intended to explore the underlying evidence – the “why” of nature-based solutions.

(For more on what nature-based solutions are, see Carbon Brief’s explainer on the topic.)

In the intervening time, the topic had quickly evolved, she said, so instead the talks focused more on how to implement such solutions effectively.

Stewart Maginnis, global director of the Nature-based Solutions Group at the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) referred in his presentation to a resolution of the World Conservation Conference, which defines nature-based solutions as “actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural or modified ecosystems, that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously providing human wellbeing and biodiversity benefits”.

Inger Andersen, executive director of the UN Environment Programme, told the conference in a pre-recorded message that nature-based solutions can provide 40% of the climate mitigation efforts until 2030 (presumably referencing a 2017 paper that showed they could cover 37% of “cost-effective CO2 mitigation” to keep warming below 2C).

However, as Maginnis pointed out, nature-based solutions have the potential to do more than just reduce emissions.

"I am worried that carbon markets are poisoning the nature-based solutions well" says Stewart Maginnis, who leads on NbS @IUCN

— Josh Gabbatiss (@Josh_Gabbatiss) July 6, 2022

Emphasises that these solutions can be used to tackle lots of societal challenges, not just cutting carbon.#NbSConference2022 pic.twitter.com/yFTWzHtZIn

As several attendees noted, they can also lessen the harmful effects of climate change on people and the environment by reducing the impact of disasters and fostering community resilience, as well as assisting in addressing biodiversity loss.

In her keynote address on the first day, Dr Pamela McElwee from Rutgers University explained some of the trade-offs that can take place when considering nature-based solutions.

"Just about everything we do for biodiversity is generally good for the climate, but the same can't be said for the reverse. A lot of things we might do for climate have negative biodiversity outcomes" says @PamMcElwee #NbSConference2022 pic.twitter.com/ZW1fanU4G7

— Josh Gabbatiss (@Josh_Gabbatiss) July 5, 2022

Then Mathias Bertram from the German Corporation for International Cooperation (GIZ) showed how the concept of nature-based solutions has historically crystallised out of the “ecosystem approach” first declared at the COP5 biodiversity summit in 2004.

Mathias Bertram from @giz_gmbh highlights the road map to #cop15, and the history of ecosystem-based approaches, and key events that have taken place over the past 2 decades #nbsconference2022 #naturebasedsolutions pic.twitter.com/VWCPn6YdpN

— Nature-based Solutions Initiative, Oxford (@NatureBasedSols) July 5, 2022

What are the biggest concerns around nature-based solutions?

While nature-based solutions could play a crucial role over the coming decades, the conference also highlighted challenges around their implementation and framing.

Marina Melanidis – founder and development director of Youth4Nature – explained the conflicting narratives around nature-based solutions in the first morning of the conference. The dominant narrative – held by governments and large organisations – is to view nature-based solutions as a “useful tool” for leveraging nature to suit our needs, she said.

However, she added that among Indigenous communities and non-governmental organisations, they are often seen as a “dangerous distraction” from the need to cut emissions from fossil fuel use, which can perpetuate the existing “unjust status quo”.

Are nature based solutions a "powerful" tool, or a "dangerous distraction"?

— Ayesha Tandon (@AyeshaTandon) July 5, 2022

Brilliant talk from @marinamelanidis on narratives and power dynamics in the nature based solutions conversation. pic.twitter.com/02A5JKulyu

In a session entitled “understanding and overcoming obstacles”, Forrest Fleischman – associate professor at the University of Minnesota’s Department of Forest Resources – told attendees that since the 1970s, the Indian government had put “huge” investment into tree planting. However, he said these measures have largely failed due to the “colonial” government legacy.

“The Indian government is unlikely to deliver on its nature-based climate solutions potential without significant reform,” Fleischman said. Instead, he suggested putting more money into community-run forest projects, which are often better managed.

"Indian forest departments are colonial enterprises, originally designed to extract profits out of Indian forests for the benefit of the UK"@ForrestFleisch1 on why Indian reforestation projects have been broadly ineffective to date.#NbSConference2022

— Ayesha Tandon (@AyeshaTandon) July 6, 2022

Meanwhile, Dr Linjun Xie from the University of Nottingham, Ningbo, explained that urban nature-based solutions in China often prioritise “green” over “eco”.

In a separate session, Diego Pacheco – head of the Bolivian delegation to the UNFCCC – warned against the “commodification” of nature. He told attendees that the 21st century has seen a shift towards a market-centred “green economy”, which is based on a western paradigm and exploits nature for human gain.

Instead, Pacheco proposed a “Mother Earth” approach, which strengthens the links between people and nature and is based on the views of Indigenous people.

Diego Pacheco warns that a market-centred "green economy" can exploit nature for human gain, and is based on a western paradigm.

— Ayesha Tandon (@AyeshaTandon) July 6, 2022

He invites the Nature Based Solution community to focus on "mother earth centred actions" – based on indigenous peoples' views.#NbSConference2022 pic.twitter.com/mabZqUUlcP

How can nature-based solutions be scaled up effectively and fairly?

Much of the conference’s focus was on how nature-based solutions could be governed and expanded effectively.any of the speakers made it clear that this would require engagement with those living in targeted areas.

One session that focused on “fostering inclusive and restorative land use governance” began with a talk by Dr Constance McDermott from Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute, who discussed the various ambitious, global targets for the sector – a recent example being the zero deforestation pledge made at COP26.

McDermott drew on years of field work, explaining how local circumstances and numerous interacting – and sometimes conflicting – factors can compromise these kinds of international goals. She said:

“Those targets, if they don’t more seriously take into account issues of equity than they have so far, are more than likely to miss their mark.”

"We need to urgently stop offloading the costs and burdens of sustainable initiatives onto those not at the table"

— Josh Gabbatiss (@Josh_Gabbatiss) July 6, 2022

Constance McDermott from @uniofoxford emphasises the need to consider equity when setting big targets (eg. zero deforestation by 2030)#NbSConference2022 pic.twitter.com/mvFXJsey19

Other speakers continued on this theme, emphasising the need to work with and understand the needs of people on the ground, before embarking on nature-based solutions.

Noting that people already manage around three-quarters of the planet’s surface, Prof Rachael Garrett from ETH Zurich pointed out the need to appreciate trade-offs when planning nature-based solutions, citing case studies involving cattle farming in Brazil and forest restoration in Malawi:

“Embedded in the conversation over the last day has been an assumption that there’s always co-benefits. That may not be the case.”

Yellow areas are ideal for restoring nature but also have lots of people living there – so are they actually ideal?@rach_garr points out the need to centre people on nature-based solutions.#NbSConference2022 pic.twitter.com/l4rmYxpz8P

— Josh Gabbatiss (@Josh_Gabbatiss) July 6, 2022

Dr Eric Kumeh Mensah of the Natural Resources Institute Finland provided a detailed example of this in practice, illustrating some of the issues that arose over the course of an agroforestry project in Ghana.

An example of this from @KumehMensahE, who explains problems with a project delivering cocoa agroforestry in Ghana 🇬🇭

— Josh Gabbatiss (@Josh_Gabbatiss) July 6, 2022

There's a sense that the project has prioritised ecosystems over livelihoods. Lots of responsibility on local people, with few incentives.#NbSConference2022 https://t.co/X1iLgwa8dz pic.twitter.com/0GheCsQBjM

The final day saw numerous speakers discuss how to scale up nature-based solutions in the UK, with representatives from farming, NGOs, business and the civil service pitching in on the role that the government should play in supporting those involved.

Laying out a vision for a joined-up, functioning policy landscape for the UK, Alexandre Chausson from the Nature-based Solutions Initiative said that nature-based solutions could address 33 of the 34 climate risks identified as requiring urgent attention in last year’s UK climate change risk assessment from the Climate Change Committee (CCC).

Who should pay for nature-based solutions?

One of the most popular questions from the audience was about who should pay for the implementation of nature-based solutions.

According to Vanessa Perez-Cirera, chief economist at the World Resources Institute, an additional $824bn per year of investment into nature is needed. She referred to this as the “nature funding gap”. She noted that considering carbon markets or offsetting as tools that could fill this gap, is “a misconception”.

Meanwhile, Helen Magata, communications officer of an indigenous peoples’ organisation Tebtebba, mentioned that nature-based solutions are part of “daily rhythm” for indigenous people. However, reports suggest that less than 1% of climate finance actually reaches them.

Speakers were broadly united by the idea that nature-based solutions should be financed by joint efforts of public, private, international and domestic sources.

However, when summarising the key conclusions from the financing session at the end of the second day, the organisers stated that “overarching constraints in unlocking private finance remain due to lack of capacity to ensure social safeguards materialise on the ground as well as lack of investor risk appetite”.

In his talk, economist Prof Edward Barbier from Colorado State University highlighted the high potential for economic returns from investing in nature.

💰"For every $ spent on conservation, almost $7 more are generated in the economy after just 5 years" in low-middle income countries.

— Ayesha Tandon (@AyeshaTandon) July 7, 2022

Huge economic returns from investing in nature highlighted by Ed Barbier, #NbSConference2022 pic.twitter.com/6lvxoUz1LR

He concluded that “there is something fundamentally wrong with our economic approach to nature” showing a slide summarising environmentally harmful subsidies in the US.

The total value of environmental harmful subsidies globally – $1.8 trillion US/yr – is the same as what Canada produces in total economic goods and services each year highlights Prof Ed Barbier – @ColoradoStateU, @CSULiberalArts #nbsconference2022 pic.twitter.com/hAabvpMb4S

— Alexandre (@AChausson) July 7, 2022

The day before, Dr Rhian-Mari Thomas, chief executive of the Green Finance Institute, provided another illustration of profitable investment in nature. She brought up the Tropical Asia Forest Fund 2 project example, in which about £100m is invested. The project is expected to yield returns of up to 16%, Thomas said.

What is the role of Indigenous and local communities?

In her opening address, Seddon said the growing recognition of the “deep interdependency” between societal wellbeing and ecosystems shows that “western science has finally caught up with that which Indigenous people have known for a long time”. This was a running theme throughout the three-day conference.

In a session dedicated to the crucial role of Indigenous and local people, Musonda Kapena, director at Namfumu Conservation Trust in Zambia, told attendees that she is known as “mother of caterpillars” in her local community.

Women and children in her community harvest caterpillars – which are a delicacy in the region – she explained. As caterpillars become increasingly popular abroad, she explained that respecting local knowledge is crucial to managing the caterpillar harvest sustainably.

Musonda Mumba on the importance of local and indigenous knowledge for #naturebasedsolutions: when an old man dies, a library burns to the ground#nbsconference2022 @naturebasedsols pic.twitter.com/yiSRcA02qs

— ECI_bio (@ECI_bio) July 6, 2022

In the same session, Dr Yiching Song outlined the Farmer Seed Network that she leads in China. She explained that farmers share seeds and knowledge through the network, allowing them to document Indigenous knowledge and create links between communities.

The session also featured Dismas Partalala Meitaya, from Tanzania’s Ujamaa Community Resource Team. He explained the importance of Indigenous land conservation and community land ownership, using a case study of the Hadzabe community, which is one of the last hunter gatherer groups in the world.

Meitaya and his team helped the community to secure more than 100,500 hectares of land and natural resources. This has improved both livelihoods for the community and biodiversity in the area. “Without land rights, everything else fails”, he told the conference.

However, issues with promoting nature-based solutions in Indigeonous communities were also raised in this session.

Nature based solutions are part of "daily rhythm" for Indigenous people, says @HelenMagata

— Josh Gabbatiss (@Josh_Gabbatiss) July 6, 2022

But we don't know how much climate finance is going directly to Indigenous groups – reports suggest less than 1% reaching them #NbSConference2022 pic.twitter.com/9AqVDeT32o

Marisol García – a Kichwa youth leader from Peru – told the conference that the current model of nature-based solutions “violates” Indigenous rights. She added:

“We don’t think that nature-based solutions are anything new. Rather, this is a model of life that our ancestors have been promoting over hundreds of years. And now unfortunately, these are seen as a way to legalise pollution and generate wealth in our forests for a few very privileged people.”

How can nature-based solutions avoid ‘greenwashing’?

“There are major concerns that nature-based solutions are being used in greenwashing,” said Seddon at the start of the conference, emphasising – as many attendees did – that “nature-based solutions are not an alternative to keeping fossil fuels in the ground”.

Attendees aired their critiques of companies harming local communities by buying up land and of governments in developed countries relying on developing nations to offset their emissions.

Big concerns about corporations buying up land and slapping trees all over it, shutting people out, says @KathrynABrown

— Josh Gabbatiss (@Josh_Gabbatiss) July 7, 2022

“The idea of rewilding is getting quite a bad reputation, because of that”

She adds there is growing appetite for projects to include community engagement pic.twitter.com/OsbXsUiztE

One session in particular aimed to address these concerns around nature-based solutions head on, focusing on their role in achieving net-zero. Dr Steve Smith, executive director of Oxford Net Zero, opened it up by asking what the role of companies and government could be:

“How do we make sure that this net-zero momentum we’re seeing is focused into real action…and not diverted into greenwashing?”

Dr Stephanie Roe, climate lead at WWF and a lead author for the IPCC sixth assessment report, laid out the potential of nature-based solutions to contribute to climate mitigation.

"Are these countries going to give their emission reductions to other countries with higher residual emissions? Are they going to give them to companies?" she asks

— Josh Gabbatiss (@Josh_Gabbatiss) July 5, 2022

During the same session, Dr Aline Soterroni highlighted the shortcomings of the Brazilian government’s climate policies. Her team’s modelling highlighted the gulf between Brazil’s “unambitious” new climate plan and its 2050 net-zero target, which she said the nation would not meet unless it addressed deforestation.

Modelling by @alinesoterroni of deforestation in Brazil shows that by 2050:

— Josh Gabbatiss (@Josh_Gabbatiss) July 5, 2022

"Baseline" scenario with no policies to curb deforestation will see area size of 🇫🇷 cut down

Even a scenario where Forest Code is followed will see area size of 🇮🇹 legally cut down#NbSConference2022

With the audience primed on the potential for nature-based solutions, Kaya Axelsson, a net-zero policy engagement fellow at University of Oxford, reflected on her conversations with companies about net-zero.

She noted that while the Net Zero Tracker – an initiative documenting the adoption of net-zero targets – has recorded a strong upward trend in firms setting such goals, around two-fifths have no conditions on the quality of the offsets they intend to use. Some told her this was due to a lack of clarity and fear of criticism:

“One company in particular told me they felt it was a circular firing squad…when you announce how you’re offsetting or what credits you’re investing in.”

Axelsson also explained the Oxford principles for net-zero aligned offsetting, which were established to ensure only high-quality offsets are employed.

Principles for aligning the (currently pretty dodgy) offset market with net-zero, from @KayaAxelsson. Firms should:

— Josh Gabbatiss (@Josh_Gabbatiss) July 5, 2022

🏭Prioritise reducing their own emissions

↩️Shift to CO2 removal rather than avoided emissions

🪨Shift to long-live storage eg. geological#NbSConference2022

Later in the conference, there was some pushback against the principles as Lorenzo Bernasconi, who works in financing forest projects at Lombard Odier Investment Managers, said they hampered investment in high-quality nature-based solutions.

Can nature-based solutions be effectively implemented?

While there are many issues with the implementation of nature-based solutions and hurdles to be overcome, the conference was also full of examples of success stories.

During a panel about governing nature-based solutions, Chairil Abdini from the Indonesian Academy of Sciences, spoke about the negative environmental impact of palm oil industry in Indonesia, which affects high carbon stock forests and peatlands.

However, he said the Indonesian ministry of environment had started a project for rehabilitation of land and forest in Tesso Nilo national park with strong community involvement. Afterwards, noted Abdini, “the villagers admitted that the land and forest rehabilitation program really touched and empowered the community so that it brought economic benefits”.

Having focussed on farming and rural solutions for most of the conference, the final session turned to urban nature-based solutions. Rob Carr explained how the UK Environment Agency “nibbles away” at a range of smaller projects through what he called “urban tinkering” – rather than attempting large-scale, time-consuming projects.

For example, he told attendees that 98% of salt marsh along the Tyne estuary has disappeared over the past few centuries – so the team organised a project to increase sedimentation there. He also presented plans for “floating ecosystems” to be installed along the river. These interventions improve not only nature, but livelihoods in the area, he said.

"Floating ecosystems" will be installed in the River Tyne, at Newcastle, next week

— Ayesha Tandon (@AyeshaTandon) July 7, 2022

A great example of urban nature based solutions by the Rob Carr, @EnvAgency #NbSConference2022 pic.twitter.com/TPQFD3Tnd2

In the panel discussion that followed, the speakers agreed that holding out for large-scale, transformative changes can halt progress, and so all scales of solution – including “nibbling, tinkering and planning” are important.

Meanwhile, Carr told the conference that “envy” between cities can be an important driver of progress, encouraging city planners to learn from one another to implement nature-based solutions that work well.

What is the role of nature-based solutions in international negotiations?

Attendees discussed the rise to prominence of nature-based solutions in international negotiations on climate change and biodiversity.

Stewart Maginnis from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) said that over the past few years a “solid foundational basis” for nature-based solutions had been built.

However, he said that the appearance of nature-based solutions in the multilateral framework would help to scale them up and provide investor confidence. He also said it helped to boost recognition for the links between climate and biodiversity:

“Only a few years ago we were told: biodiversity is over here, climate over there, never the twain shall meet…that is now clearly not the case.”

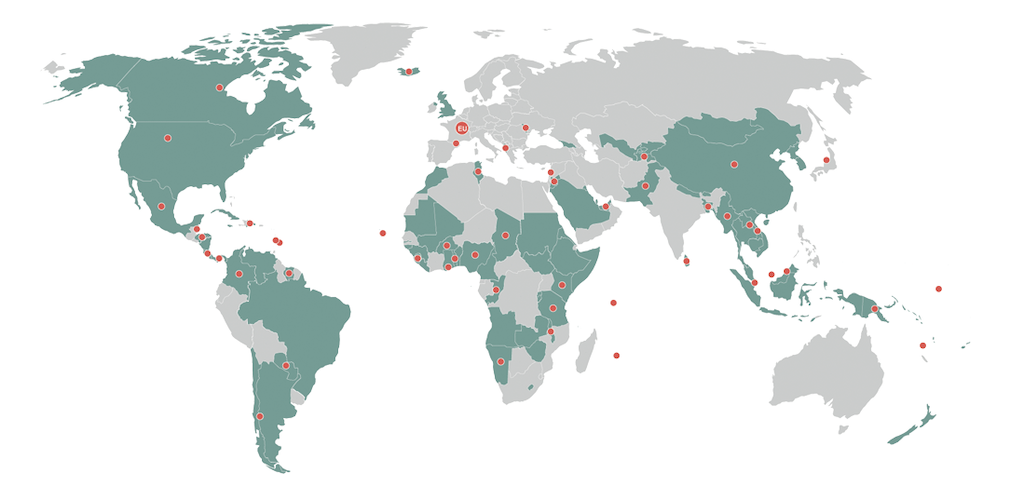

Nature-based solutions are referenced in 105 of the updated climate plans that countries have submitted under the Paris Agreement, according to the Nature-based Solutions Policy Platform. This is shown in the map below.

After a concerted effort to make it part of the final Glasgow Climate Pact, in the final days of COP26 the term “nature-based solutions” was removed from the text. In her opening address, Seddon told the audience this was evidence of the “discomfort” that remains around the term.

Manuel Pulgar-Vidal, former Peruvian environment minister and COP20 president, also highlighted the resistance to nature-based solutions that he witnessed at recent UN biodiversity negotiations in Nairobi.

At UN biodiversity talks, @manupulgarvidal says he saw lots of resistance to nature based solutions – people concerned that they will turn nature into a commodity, undermining concepts of Mother Earth and Buen Vivir.

— Josh Gabbatiss (@Josh_Gabbatiss) July 5, 2022

Says "credibility gap" must be addressed#NbSConference2022 pic.twitter.com/4KwxIVNke5

Some of this opposition could be seen in the talk given by the Bolivian lead negotiator Diego Pacheco. His nation has long opposed what it views as the commodification of nature in international negotiations.

UK environment minister Lord Zac Goldsmith spoke highly of nature-based solutions in his address and told attendees that “perhaps the most important thing we must all do is make the UN biodiversity conference [COP15 in Montreal] a Paris moment for nature – we need an ambitious new framework”.

Maginnis discussed the possibility of nature-based solutions being included in a final text from either biodiversity or climate UN negotiations, noting that there had already been an official UN “decision” using the term from the COP15 UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) meeting in Abidjan, Ivory Coast.

However, he said the world might have to be “prepared for the long game”, as the term might not be established in the final texts that emerge from COP27 climate talks in Sharm el-Sheikh this November or the COP15 biodiversity summit in Montreal.

-

Nature-based solutions: How can they work for climate, biodiversity and people?