Video: NASA produces first 3D animation of global carbon emissions

Leo Hickman

12.14.16Leo Hickman

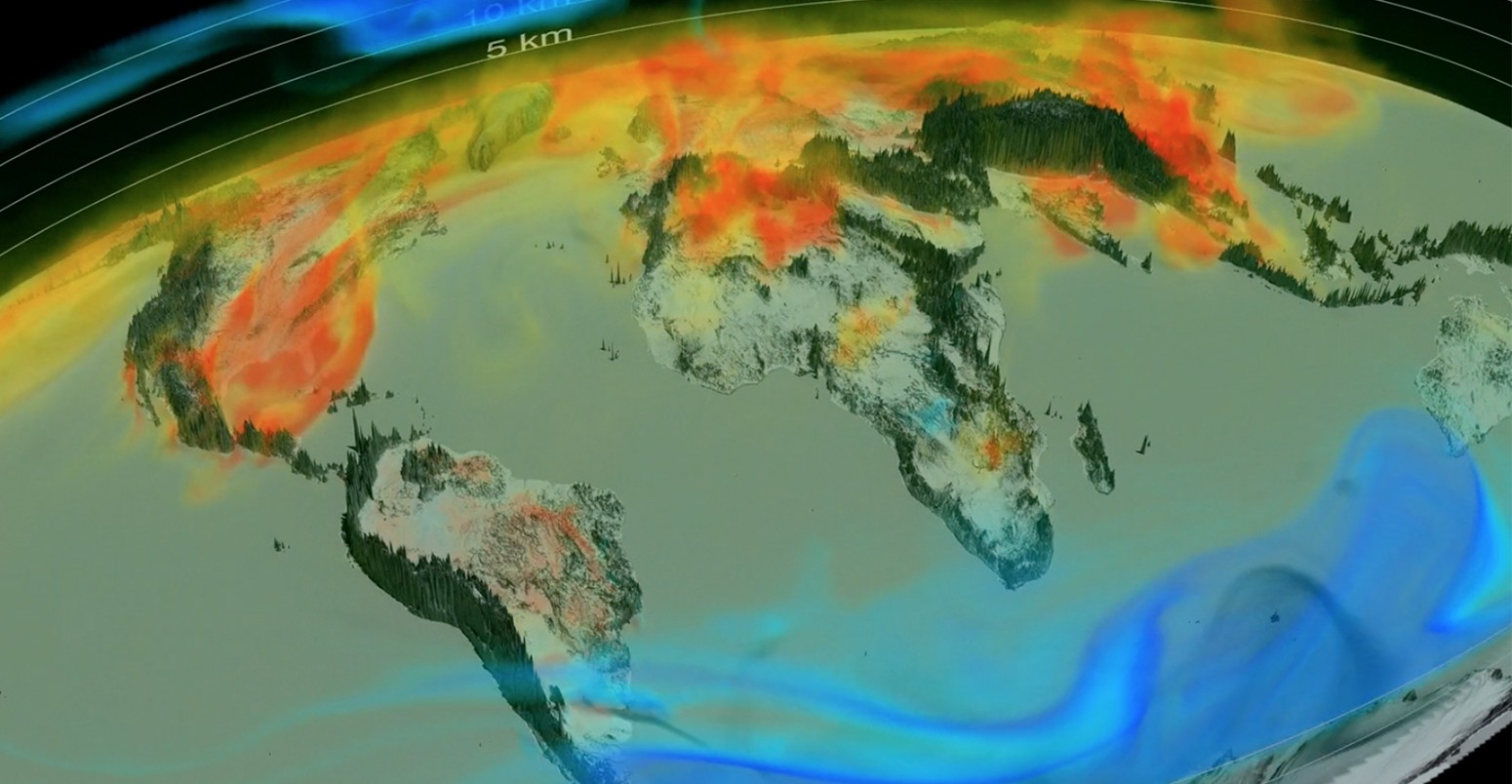

14.12.2016 | 11:42amNASA, the US space agency, has released an “eye-popping” three-dimensional animation showing carbon dioxide emissions moving through the Earth’s atmosphere over the course of a year.

It says the 3-D visualisation is “one of the most realistic views yet” of the “complex patterns in which carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increases, decreases and moves around the globe”.

The data used to produce the visualisation was collected by NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) satellite from September 2014 to September 2015. The data was then modelled and visualised by the Global Modeling and Assimilation Office at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Carbon Brief emailed some questions to NASA about the visualisation, which it says is the first of its kind. The answers below are provided by Dr Lesley E Ott, a carbon cycle scientist at Goddard’s Global Modeling and Assimilation Office, and Gregory W Shirah, who leads the development of Earth science-related scientific visualisations at Goddard.

CB: How was the visualisation “made”?

LO: The carbon dioxide field was produced by combining information from our GEOS modelling system with OCO-2 observations using a technique called data assimilation. In this merged view, the model helps fill in gaps where OCO-2 can’t observe and also provides more information about the 3D structure of atmospheric carbon dioxide, which is quite complex but can’t be observed directly from the satellite. Meanwhile, the data helps correct errors in the model’s emissions and transport patterns. This carbon dioxide analysis provides one of the most complete, data-driven views of atmospheric carbon dioxide to date.

GS: To make the actual visualisation (ie, paint the pixels), we use Pixar’s Renderman to render the images. We use Autodesk’s Maya to set up the 3D environment and we used IDL to process the data. My colleague and I actually just gave a talk at Pixar today and showed this movie to them.

CB: Specifically, what questions are you hoping it will help to answer?

LO: The main goal of OCO-2 and most carbon cycle modelling is to better understand the processes that control carbon sources and sinks. About 50% of human emissions are absorbed by plants on land and in the oceans, but scientists don’t have a good understanding of how or even where this is happening. We start by running the model with a ‘first guess’ of sources and sinks, and the data assimilation allows us to quantify how and where the model differs from the observations. Eventually, we’ll be able to use these techniques to create more accurate maps of source and sinks, and from there we can improve climate models to better predict changes in the natural carbon cycle. This analysis product is something of a mid-point. We still have a lot of work left to do to understand the carbon cycle more fully, but developing these modelling and data assimilation tools is an important advance that will help us get where we need to be.

CB: Why are these questions so important to answer?

LO: Understanding the natural land and ocean carbon sinks is critical to understanding and predicting the trajectory of climate over the coming decades. If the land and ocean can’t continue to sequester carbon at the current rate, we could see carbon dioxide accumulate in the atmosphere more quickly than we’re expecting, leading to more rapid climate change.

CB: The CO2 seems to be largely concentrated in the Northern hemisphere. Beyond this being where the majority of human-caused emissions are released, please can you explain the processes driving this and what the implications might be?

LO:The highest carbon dioxide mixing ratios are seen in the Northern hemisphere during winter months. Most of the human emissions originate from this region, but it also holds the majority of the world’s land masses and vegetation stocks, which decompose and release carbon during the winter. When plants start to grow again in the spring, you see massive amounts of carbon drawn out of the atmosphere, but not quite enough to balance out the increase from human emissions. If we ran the visualisation for a longer time period, you would see the carbon dioxide released in the north mix with southern hemisphere air, but that interhemispheric mixing can take about a year. So even though that mixing is going on here, what really jumps out is the seasonal cycle of carbon dioxide.

CB: How is this new visualisation an advance on ones produced before?

LO: Before OCO-2, we had a satellite called AIRS [Atmospheric Infrared Sounder] providing information about CO2. There’s an example of what that data looks like at https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/4184.

AIRS was designed to study temperature and moisture, primarily, but did give information about carbon dioxide in the mid- and upper troposphere. Since it has very little information near the surface to tell us about sources and sinks, it hasn’t been as widely used as the datasets from GOSAT and OCO-2.

Looking at the OCO-2 data alone is also interesting – take a look at: https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/12106

and https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/4402

The first animation shows the observations with minimal averaging at first and then switches to a view of the data averaged over larger areas to fill in the map. This is nice for giving a sense of what OCO-2 can and can’t do. It’s a huge advance over AIRS, both in terms of near surface sensitivity and accuracy. At 0.25% (or 1 parts per million, ppm), OCO-2 gives us one of the most accurate atmospheric composition measurements ever made from space. But the trade-off is that we can’t make OCO-2 observations in cloudy regions or areas with high aerosol loadings. And because the measurement technique uses reflected sunlight, there are no measurements during night or polar night. OCO-2 also has a fairly narrow swath as you see early in the first video meaning that we can only observe a subset of the world every day, even under ideal conditions. When we try to average the measurements to cover some of these gaps, you can see that we get a sense of where CO2 is being taken up and released, but we still have large gaps in coverage in high-latitude regions and that sense of how CO2 moves through the atmosphere really isn’t there.

As highlighted in the new animations, the alternative method of creating CO2 maps from observations through assimilation into a weather model (compared to the OCO-2 averaging shown above), preserves much more detail about the atmospheric transport. The model brings in information in areas without observations, but it also brings all the vertical information since the OCO-2 measurement is column only. This animation is also new and produced from the same dataset.

That really shows you how the data assimilation technique is working. Early on as the movie is going fairly slowly, there are some nice examples of how the model is helping us interpret what the observations are capturing. In the observations, we can see transitions between high and low CO2, but the merged product underlay helps us understand that those are due to the movement of weather fronts or plumes of fire emissions off of Africa. We chose to highlight the 3D visualisation which is flashier, but this one is also quite informative.

GS: We have created some 3D (volumetric) visualisations in the past – I think of CO2 from AIRS – but they were very limited. For example, relatively small/regional areas, like Southern California, or single snapshots in time from a swath of satellite data. To my knowledge, this is the first time a global, time-varying CO2 model has been shown this way. I’m not even sure if any global model has been shown this way.