Mystery over ‘unexpectedly large’ emissions from Africa’s tropical ecosystems

Daisy Dunne

02.15.24Daisy Dunne

15.02.2024 | 3:51pmA few years ago, scientists studying satellite data discovered that there was an “unexpectedly large” source of CO2 emissions coming from tropical Africa, particularly over parts of Ethiopia and South Sudan.

This mysterious emissions source was so large, in fact, that if this region were a country, it would have been the second-largest emitter in the world, after China, in 2016 – releasing a total of 6bn tonnes of CO2, according to the study.

Now, newer research calls these results into question. Rather than using satellite data alone, it uses data taken by scientific aircraft travelling up and down the Atlantic Ocean off the western coast of tropical Africa.

This study finds that tropical Africa’s land acts as a net emitter of CO2 in the dry season, when practices such as biomass burning reach a peak, and a net sink in the wet season, when plants grow faster and take in more CO2 from the atmosphere. Thus, it concludes, tropical Africa’s land can be considered “neutral” in terms of its CO2 emissions.

However, the scientists that first reported the mysterious emissions tell Carbon Brief that they disagree with the new conclusions – and have a plan to explain where such large emissions could be coming from.

With neither study using data taken on the ground in Africa nor including African scientists, authors on both papers acknowledge the need for ground-based CO2 measurements to help solve the mystery.

Differing data

Africa is home to one-third of the world’s tropical rainforests, 3% of the world’s peatlands – including the world’s most extensive tropical peatland – and the majority of the world’s tropical savannahs. All of these ecosystems store large amounts of carbon.

Though the African tropics are a globally important carbon store, there have been few studies looking into the extent of year-to-year CO2 emissions from the land in this region.

Back in 2019, a study in Nature Communications sought to understand the extent of annual CO2 emissions from tropical Africa using data from Japan’s greenhouse gases observing satellite (GOSAT) and NASA’s orbiting carbon observatory (OCO-2).

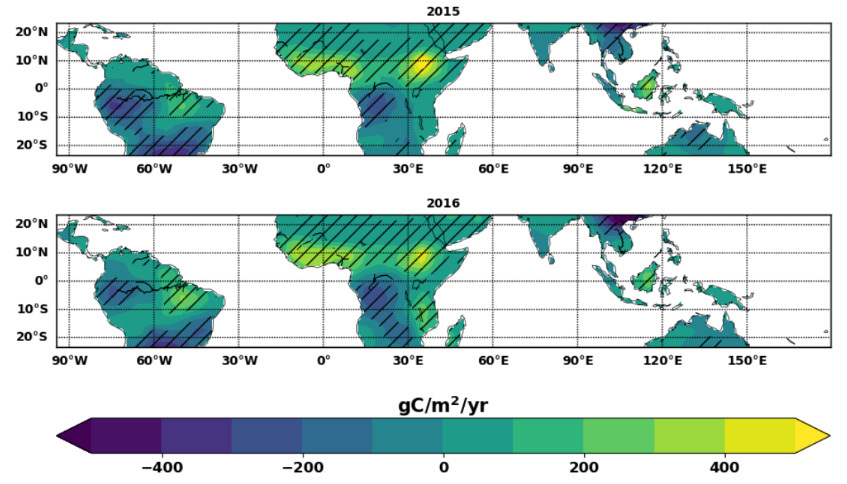

The results showed that net CO2 emissions from Africa’s tropical land – the difference between the amount of CO2 absorbed and emitted by the land – totalled 5.4bn tonnes and 6bn tonnes in 2015 and 2016, respectively.

The maps below, taken from the paper’s supplementary information, show the extent of CO2 emissions from tropical land in 2015 and 2016. On the map, dark blue shows regions that acted as carbon sinks while yellow shows regions that were net emitters of CO2.

On the maps, a large yellow spot covers parts of Ethiopia and South Sudan – the source of the “unexpectedly large” emissions from Africa’s tropical land, the study’s lead author Prof Paul Palmer, a researcher of geosciences from the University of Edinburgh, told Carbon Brief back in 2019.

The newer study, published in the journal Global Biogeochemical Cycles, uses a different approach to study annual CO2 emissions from Africa’s tropical land.

This team of researchers used the NASA DC-8 Airborne Research Platform, an aeroplane that has been fitted out with equipment to conduct scientific research.

For four days across the northern hemisphere’s four seasons spread over the years 2016-18, the researchers flew south to north over the Atlantic Ocean to the west of tropical Africa, collecting CO2 measurements from the ocean surface to around 35,000 feet.

This approach allowed researchers to study the exhaust plume blown over to the Atlantic Ocean from tropical Africa. This plume contains particles such as dust, soot and wildfire smoke – along with gases such as CO2 .

The researchers then compared their data to estimates from models using the satellite data from the 2019 study.

The aircraft data found that Africa’s tropical land released far smaller emissions in the dry season, when compared to the estimates derived from satellite data. This led the researchers to conclude that the satellite data used in the 2019 study could have overestimated CO2 emissions from tropical Africa.

Instead of Africa’s tropical land being a large net source of CO2, the newer study concluded that it could actually be “neutral” in terms of annual CO2 emissions, says lead author Dr Benjamin Gaubert, a project scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Our findings suggest northern tropical Africa is a carbon source in the dry season and a sink in the wet season, with an annual exchange of around zero. Much of the seasonal biomass burning is inherently balanced over the year by photosynthetic uptake from grasses and shrubs.”

Conclusions questioned

Palmer, the author of the 2019 study, is not convinced by the new findings.

He argues that, because the aircraft data was collected over the Atlantic Ocean, to the west of tropical Africa, it is likely to be much more sensitive to CO2 plumes travelling over from western tropical Africa than from eastern tropical Africa – where his study found that most of the emissions were actually occurring. He tells Carbon Brief:

“I suspect – though I’m not 100% sure – that the team have shown with their analysis that west Africa, which is dominated by biomass burning, is close to neutral [for CO2 emissions], which would be less of a surprise.”

He added that while the Atlantic Ocean does receive plumes of CO2 blowing over from Africa’s tropical land, it is also likely to be affected by other sources of emissions from other parts of the world, muddying the ability to pinpoint emissions to specific regions.

Responding to these points, Dr Britton Stephens, co-author of the newer study and a senior scientist in the Earth Observing Laboratory at NCAR, tells Carbon Brief:

“It is true that the aircraft have a relatively broad region of influence that may not correspond precisely to the strongest postulated emission source of the [2019] study.”

He adds, however, that the emissions source from eastern tropical Africa identified in the 2019 study has not been exactly replicated by other research efforts using satellites. Instead, these studies typically produce “similar annual region-wide sources with very different within-region spatial patterns”.

Prof Emanuel Gloor is a researcher of CO2 emissions from tropical land at the University of Leeds, who was not an author on either paper. (He did act as a reviewer for the newer study.)

He tells Carbon Brief that the findings of the newer study – that Africa’s tropical land is neutral in CO2 terms – is much more in keeping with scientists’ understanding of the global carbon cycle:

“Essentially the result they find is exactly what you would expect.”

Mysterious emissions

As Gloor sees it, there were several issues with the 2019 study.

One of the major ones, he says, was that the scientists concluded that there could be a very large source of CO2 emissions coming from parts of Ethiopia and South Sudan – an area not only with very little infrastructure and commercial activity, but also very little forest cover. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Where would these emissions be coming from if they were really coming from Ethiopia? That’s not where you have massive amounts of biomass.”

Although the region is not covered by large areas of forest, it is home to some very carbon-rich soils, the 2019 study noted.

At the time, the scientists suggested that land degradation and deforestation could have potentially caused large amounts of carbon to be released from soils, with Palmer telling Carbon Brief in 2019:

“Substantial changes in land use over a region with high levels of soil organic carbon are conditions that could potentially release carbon from the soils.”

The detected CO2 spike could have also been influenced by the 2015-16 El Niño event, which was one of the strongest on record, another scientist not involved in the research told Carbon Brief at the time. (Warming can cause soils to release CO2 at a higher rate.)

Speaking to Carbon Brief in 2024, Palmer says that his research team do now have a firmer idea of where such a large amount of CO2 emissions could be coming from in the region comprising Ethiopia and South Sudan.

However, he declined to give more details on what this source was, arguing that it was still an area of active research and saying that he hoped to soon publish a research paper on his findings.

Data drought

Neither study uses data taken on the ground in Africa nor includes African scientists.

This is amid a backdrop of unequal participation for African scientists and institutions in global climate research.

Previous analysis by Carbon Brief found that just 1% of the most highly-cited climate research papers from the years 2017-21 featured African scientists.

And further Carbon Brief analysis showed that Africa has the lowest density of weather stations of any continent – hamstringing the ability to study how climate change could be affecting factors relevant to carbon loss from ecosystems, such as air and soil temperatures, soil moisture, rainfall and cloud cover.

Africa is the world’s second-largest continent and encompasses 20% of Earth’s land surface, meaning a lack of understanding of how its ecosystems are changing could hold consequences for scientists’ understanding of the global carbon cycle.

Carbon Brief asked the authors of both of the papers whether it was a weakness to not include data taken on the ground in Africa.

Stephens agrees that having “ground-based CO2 measurements in the region would be a big help”.

He adds, however, that to fully capture how emissions disperse in the atmosphere, these measurements should be complemented with a “systematic programme of airborne observations” – something his colleagues “recently started pursuing”.

Palmer also agrees that having on-the-ground measurements would have been preferable.

He adds that his team did have plans to travel to the region where they detected the large source of CO2 emissions via satellite data in order to take on-the-ground measurements. However, ongoing conflicts in South Sudan and Ethiopia made this impossible, he says.

-

Mystery over ‘unexpectedly large’ emissions from Africa’s tropical ecosystems