Met Office: A review of the UK’s climate in 2024

Multiple Authors

01.28.25The year 2024 was the fourth warmest on record for the UK, behind only 2022, 2023 and 2014.

In this review, we look back at the UK’s climate in 2024 to highlight how the key events of the year fit into the wider picture of long-term human-caused climate change. We find:

- Eight months of the year were warmer than average.

- Spring was the warmest on record for the UK, which saw a record-high average temperature for May.

- February was the second warmest on record for the UK and December the fifth warmest.

- In contrast, the summer months of June, July and September were slightly cooler than average.

- On 28 January, a strong Foehn effect resulted in a temperature of 19.9C at Achfary, Sutherland, marking the highest temperature for January since records began.

- The year was relatively wet, with 7% more rainfall than average, making it the UK’s 17th wettest in a series going back to 1836.

- Oxfordshire, Wiltshire, Gloucestershire, Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire saw their second-wettest year on record, driven by large rainfall totals in February and September.

- Storm Lilian in August marked the first time that storm names reached ‘L’ in the alphabetised list since storm naming was introduced in 2015.

- An attribution study found that rainfall in the winter season of 2023-24 was 20% more intense due to human-caused climate change. It also showed the amount of rainfall observed during the season was 10 times more likely.

(See our previous annual analysis for 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019 and 2018.)

The year in summary

The Met Office relies on the long-running HadUK-Grid dataset to place recent UK weather and climate into its historical context. The gridded, geographically complete dataset combines observational data for monthly temperature since 1884, rainfall since 1836 and sunshine since 1910.

Unless stated otherwise, the rankings of events and statements (such as “warmest on record”) in this article relate to the HadUK-Grid series.

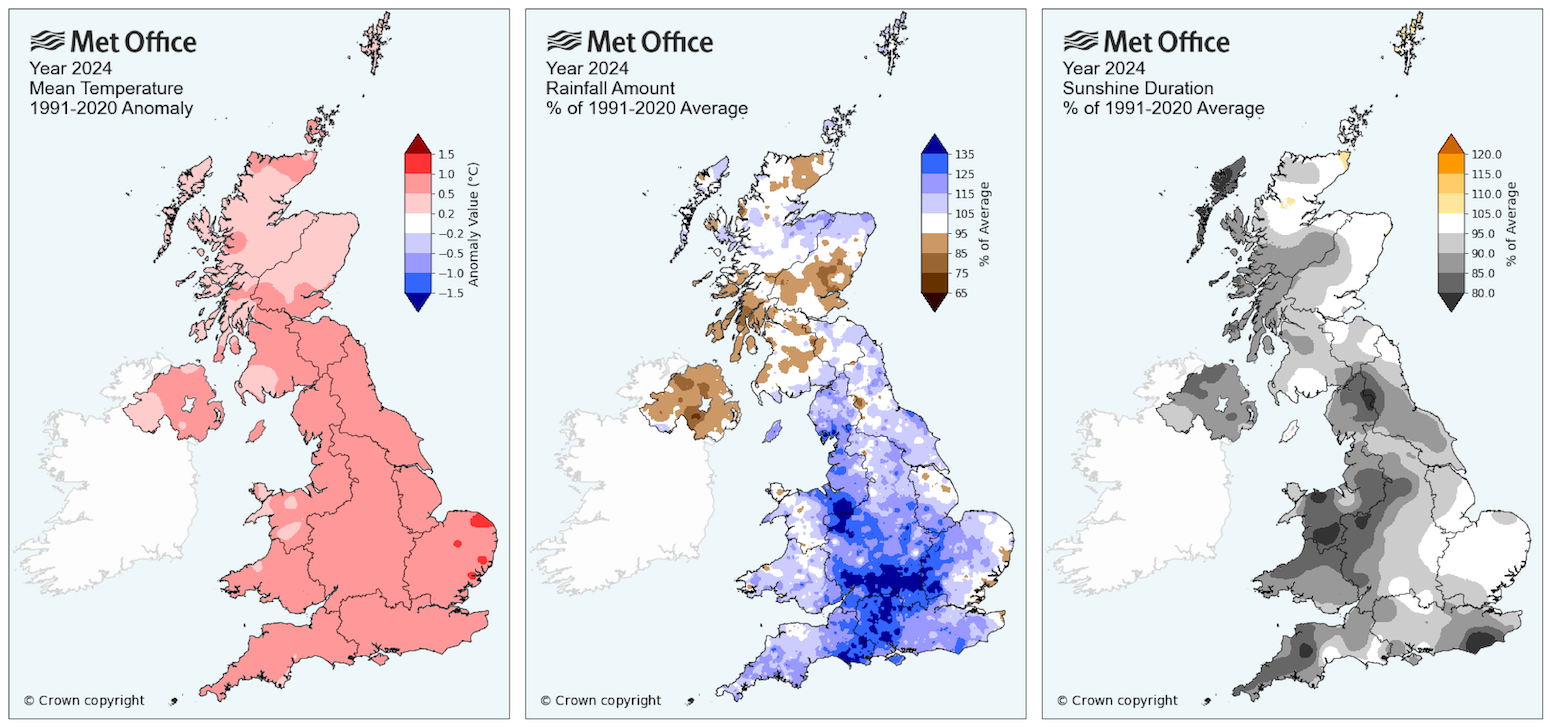

The “climate anomaly” maps below show the difference between the average temperature (left), rainfall total (middle) and sunshine duration (right) between 2024 and the 1991-2020 period. In other words, they show how much warmer, cooler, wetter, drier, sunnier or cloudier the year was than average.

The maps show that the whole country was warmer than average, with slightly lower temperature anomalies in Scotland, and slightly higher anomalies seen in East Anglia.

Rainfall shows more regional variation, with the wettest regions relative to average in central and southern England, but a slightly drier year than average for Northern Ireland and parts of Scotland.

Meanwhile, it was a relatively dull year across the country with lower-than-average sunshine across the vast majority of the UK, particularly in western regions.

The UK annual average absolute temperature for 2024 was 9.78C, which is 0.64C above the 1991-2020 average.

This makes 2024 the fourth-warmest year since records began, coming only after 2022, when the average temperature was 10.03C; 2023, when the average temperature was 9.97C; and 2014, when temperatures averaged at 9.88C. Rounding off the top-five warmest years on record is 2006, when the average temperature was 9.70C.

The timeseries plot below shows how average temperature in the UK has followed a clear long-term warming trend since the 1960s.

Daily minimum and maximum temperatures have been recorded in the UK since the 19th century.

These observe the highest and lowest temperature reached during a 24-hour period which starts and ends at 9:00 GMT each day. The daily maximum temperature tends to be in the early afternoon and the minimum temperature in the hours before dawn, but not exclusively. In the winter season in particular, changes in weather patterns can result in larger swings in temperature.

In 2024, the annual average minimum temperature for the UK was the equal-warmest on record, matching the previous record set in 2023. The consequence of this has been some mild nights and far fewer frosts than normal, particularly in February and December. Meanwhile, the annual average daily maximum temperature was 8th warmest in the series.

Tracking the impact of climate change

For 2022 and 2023, attribution analysis conducted by Met Office scientists has shown that the temperatures experienced in both years were exceptional in more than 140 years of observational data, and would have been a 1-in-500 year event in a climate unaffected by humans.

However, in the context of the current climate, such average temperatures are not necessarily extreme – in fact, they now have a “return period” closer to one-in-three years.

The observed temperature for the UK in 2024 – despite being the fourth warmest on record – is not unusual when seen through the context of the warming climate. The UK has warmed by a rate that is comparable to the observed rise in the global average temperature.

The internationally-agreed observational reference period for climate averages is the period 1991-2020. Variability in the Earth’s climate means that cooler years can still occur, such as in 2010. However, it is notable that the UK has not had a year with below-average temperature since 2013.

The 2024 climate statistics continue a pattern of warming in the UK, which highlights how climate change is not a distant challenge for the future, but is happening now.

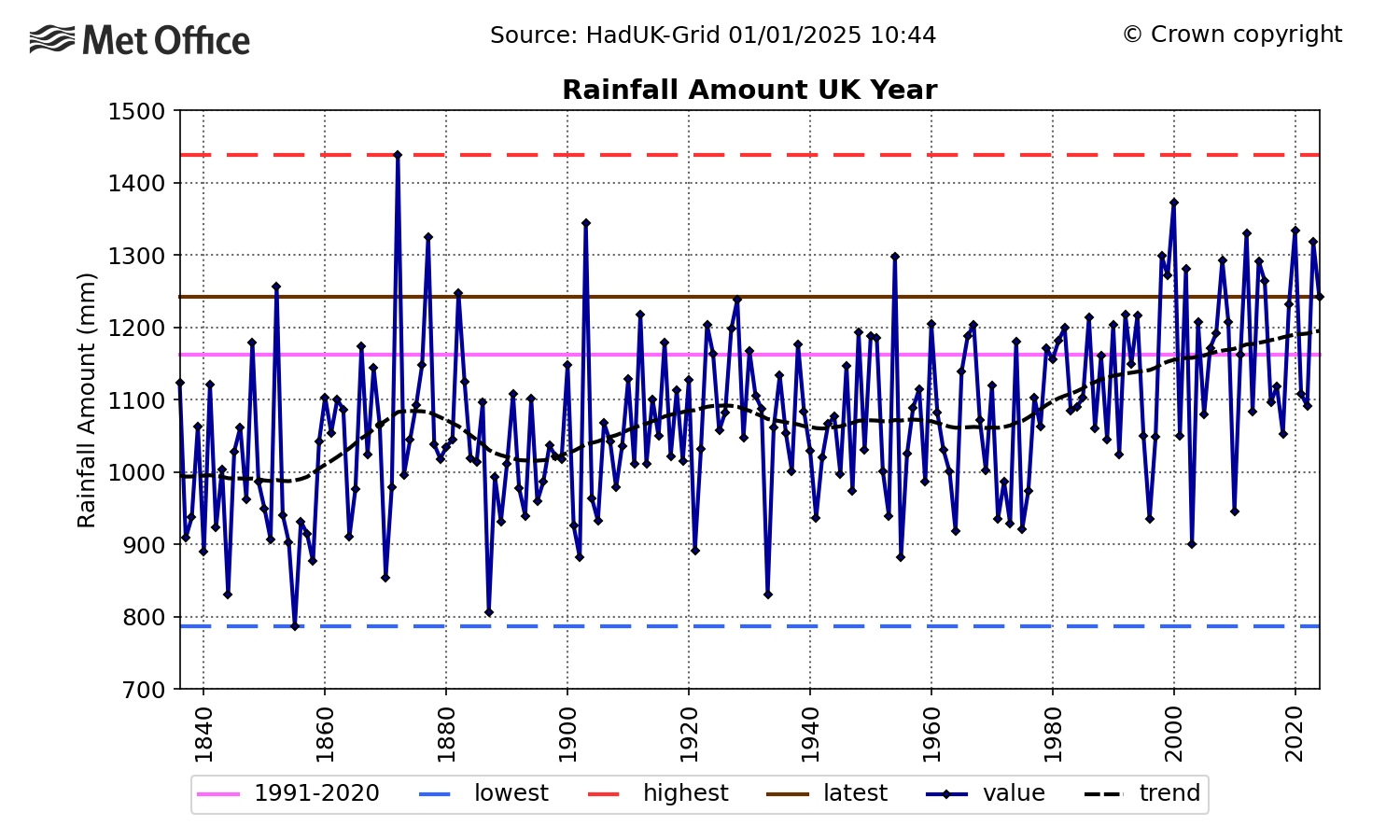

The year 2024 also fits into a general picture of a wetter climate for the UK overall. The timeseries plot below shows how rainfall in the UK has increased over recent decades.

However, the drivers of annual rainfall trends are more complex than for temperature, with annual totals masking regional and seasonal variations.

Climate projections for the UK show that winters are more likely to become wetter and summers are more likely to be drier through the 21st century.

One important driver of this change is that a warmer ocean and atmosphere can result in more water vapour in the atmosphere, which brings greater rainfall totals, or more intense rain, associated with weather systems.

However, the impact of a warming atmosphere alone is not sufficient to wholly account for the observed rainfall increase evident in the UK annual rainfall series. Other factors include decadal-scale natural variations in the climate, and the influence of climate change on large-scale circulation patterns across the northern hemisphere.

The rainfall amount of 2024 would have been considered a notably wet year if compared to much of the 19th and 20th centuries. However, last year was drier than a cluster of relatively wet years that have occurred since the late 1990s.

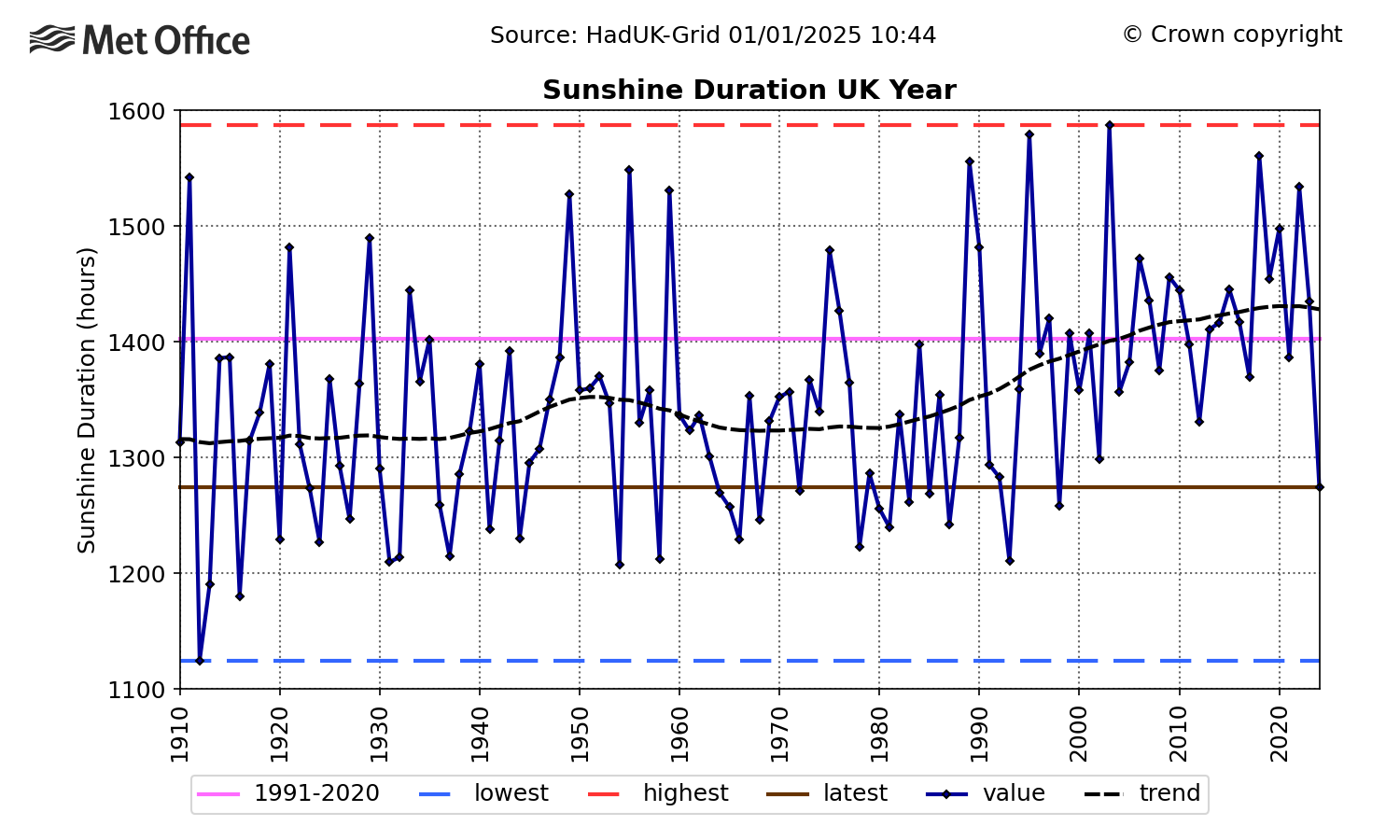

The timeseries below, which tracks annual sunshine in the UK over 1910-2024, highlights some of the vagaries of the UK’s climate.

The plot shows how 2024 was a relatively dull year for the UK, receiving the lowest hours of bright sunshine since 1998. However, this is against a backdrop of a longer-term trend of increasing sunshine in the UK, which has been especially notable since the 1980s. Sunshine amounts in winter and spring have seen the largest changes with 15-16% increases in the past decade, compared to the 1961-90 reference period.

These trends are driven by a combination of natural variability, changes in dominant circulation patterns, as well as possible human influence from increases and decreases in aerosol pollutants that influence cloud cover.

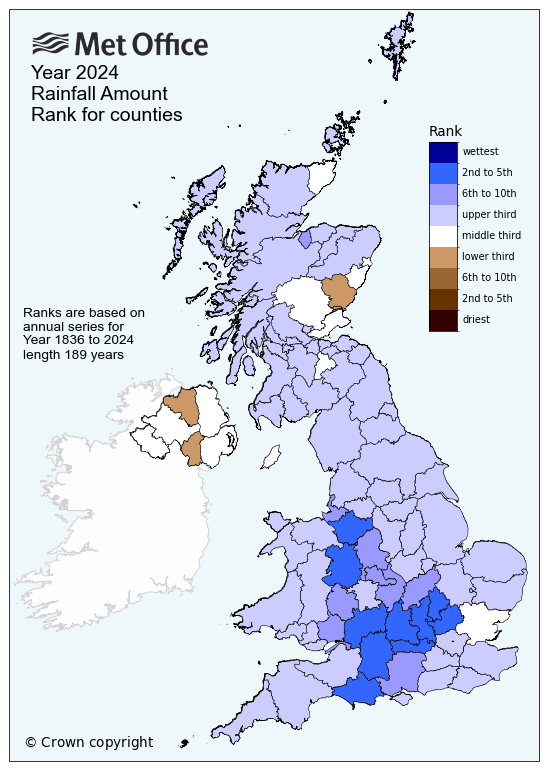

Regionally, exceptionally wet weather – particularly in February and September – resulted in parts of central and southern England having an extremely wet year overall.

Oxfordshire, Wiltshire, Gloucestershire, Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire all saw their second-wettest year, while Dorset, Cheshire and Berkshire had their third wettest and Hertfordshire and Shropshire their fifth wettest.

The year was in the top-10 wettest for a further 10 counties and in the upper third for a majority of regions. However, parts of east Scotland and Northern Ireland had slightly below-average rainfall for the year.

Weather through the year

Temperature

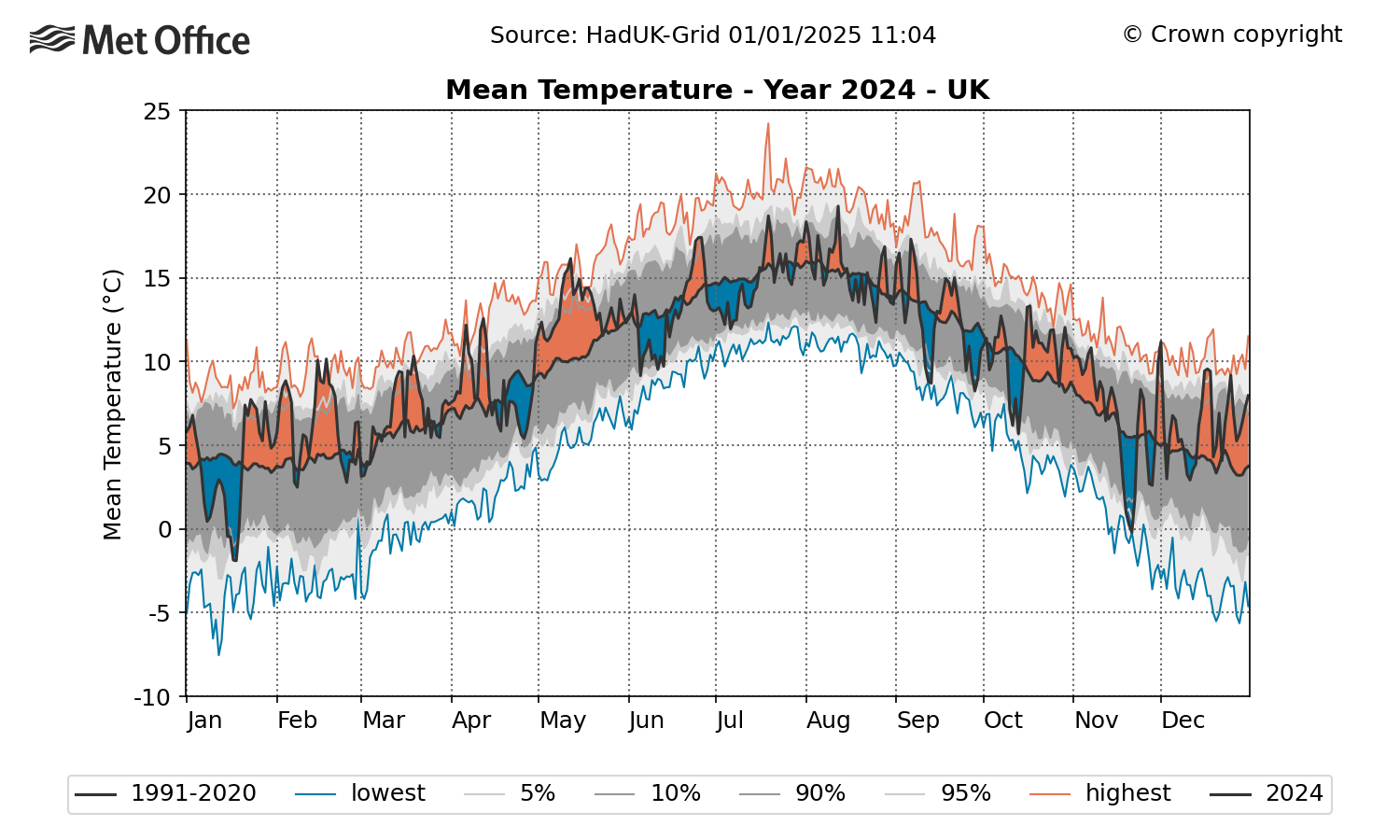

The chart below shows average UK temperature through the year, with orange highlighting periods that were warmer than average and blue showing cooler than average.

There were numerous spells of warm conditions (relative to the time of year), particularly in January, February, May and December. Overall, 60% of the year (220 days) was warmer than average and 40% (146 days) was cooler. A total of 13% (49 days) was above the 95th percentile (that is, in the top 5% warmest for the time of year). Cold snaps were not common and relatively short-lived, with only 3% (12 days) below the 5th percentile (that is, in the top 5% of coldest days for the time of year).

The highest maximum temperature of the year was 34.8C, recorded in Cambridge on 12 August during a relatively short hot spell in an otherwise unremarkable summer. The lowest minimum temperature of the year was -14.0C, recorded at Dalwhinnie in the Scottish Highlands on 17 January.

Extremes in temperature have increased at a much faster rate than the average, and the annual maximum temperature in 2024 – which would have once been an occasional event – is now much more common.

There were only nine years in the 20th century where the maximum temperature of the year in the climate archive exceeds the 2024 value (34.8C), but there are already eight years in the 21st century that have done so. Six of those have been in the last 10 years.

Rainfall

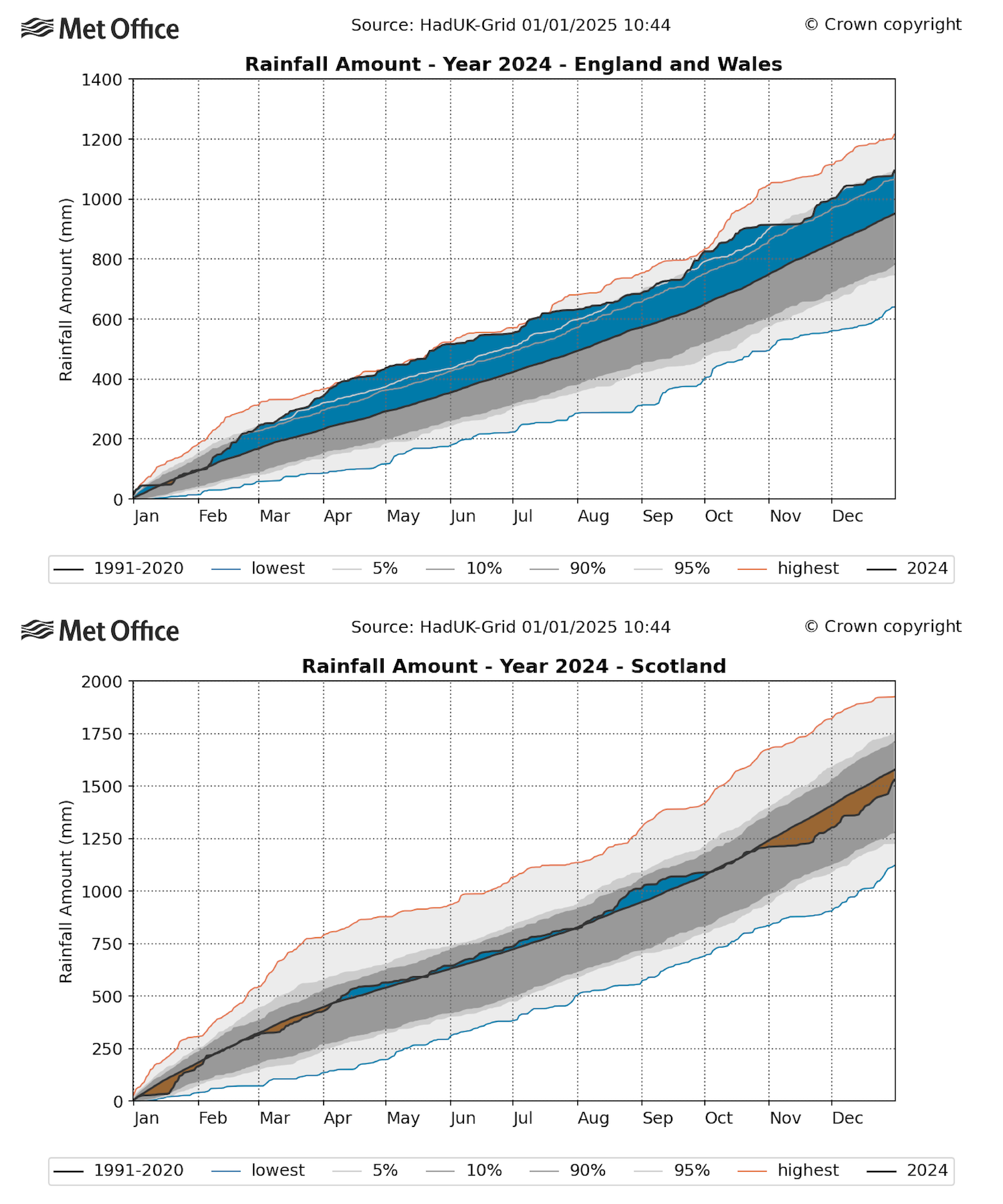

The two plots below show the accumulation of rain day-by-day through the course of the year, averaged across Scotland and for England and Wales combined.

The blue-shaded regions highlight periods when total rainfall was above average for the time of year and the orange-shaded regions times when it was below. For example, the first chart shows that Scotland had reached around 500mm by early April, which is close to average for that point in the year. (This equates roughly to a volume of water that could fill Loch Ness five times over).

In Scotland, total rainfall was close to average for much of the year. August was notably wet – the third wettest on record for western Scotland region – but this was offset by a dry autumn. A wet December, particularly for northern Scotland, brought the overall rainfall accumulation for 2024 close to average.

In contrast, rainfall in England remained well-above average for most of the year, leading to the year being the 8th wettest on record for the nation.

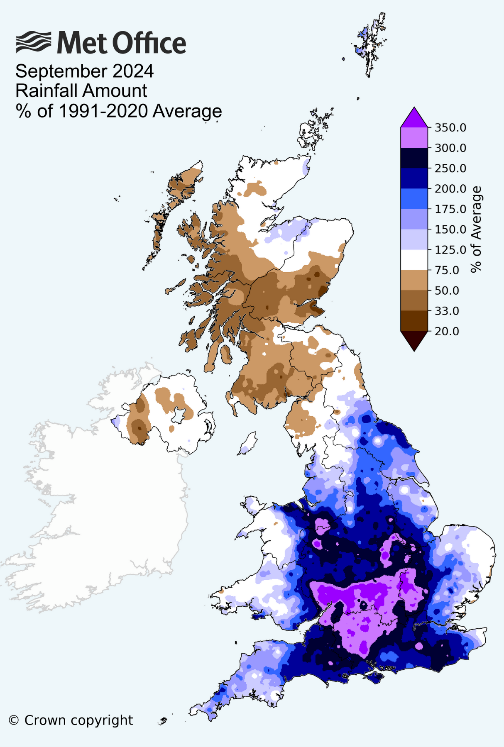

England saw its fourth-wettest February, followed by a wet March. In southern England, February saw well over 200% of average rainfall, dipping slightly to nearly 180% in March. Accumulated rainfall was further boosted by exceptional rain in September, which saw some regions recording more than 300% of average rainfall.

Storms

The Met Office has been naming storms – in collaboration with the Irish weather service, Met Eireann – since 2015. The Dutch weather service, KNMI, joined the initiative in 2019.

The 2023-24 storm season had a very active start with seven named storms occurring from September to December 2023. This continued into early 2024 with Henk, Isha and Jocelyn occurring in January.

The winter half-year from October 2023 to March 2024 was the wettest on record for both England and Wales, including in the long-running England and Wales Precipitation series (EWP), which dates back to 1766.

An attribution study – bringing together scientists from the UK, Ireland, Netherlands, Sweden and Germany – looked into the impact of climate change on the autumn-winter storm season, which ran from October 2023 to March 2024. It found that the average rainfall on stormy days has increased by about 20% due to human-caused climate change. This echoes wider studies and climate projections that suggest UK winters are likely to become wetter due to climate change.

An analysis of the intensity of storms based on wind speed in the study found that a stormy season was slightly less likely because of climate change. However, other studies, using other methods, have suggested an increase in storminess is likely in a future climate. The diverging findings highlight how uncertainty remains about the response of storm systems affecting the UK in a changing climate, and underscores the need for ongoing research on this topic.

Two red warnings for wind were issued in 2024. These were for storm Isha in January, which affected north-east Scotland and storm Darragh in December, which affected west Wales. The two wind storms were the UK’s most powerful since storm Eunice in February 2022.

| Storm name | Date/s of impact in UK | Maximum wind gust | Number of observing sites recording wind gusts over 50 knots |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023-2024 names | |||

| Henk | 2 January | 82 knots (94 mph), Needles, Isle of Wight | 37 |

| Isha | 21-22 January | 86 knots (99 mph), Brizlee Wood, Northumberland | 92 |

| Jocelyn | 23-24 January | 84 knots (97 mph) Capel Curig, Gwynedd | 50 |

| Kathleen | 6-7 April | 66 knots (76 mph), Loch Glascarnoch, Ross&Cromarty | 30 |

| Lilian | 22-23 August | 64 knots (74 mph), Capel Curig, Gwynedd | 16 |

| 2024-2025 names | |||

| Ashley | 20-21 October | 71 knots (82 mph) Aberdaron, Gwynedd | 46 |

| Bert | 22-25 November | 71 knots (82 mph) Capel Curig, Gwynedd | 32 |

| Conall | 27 November | 51 knots (59 mph) Needles, Isle of Wight | 1 |

| Darragh | 6-7 December | 83 knots (96 mph) Berry Head, Devon | 58 |

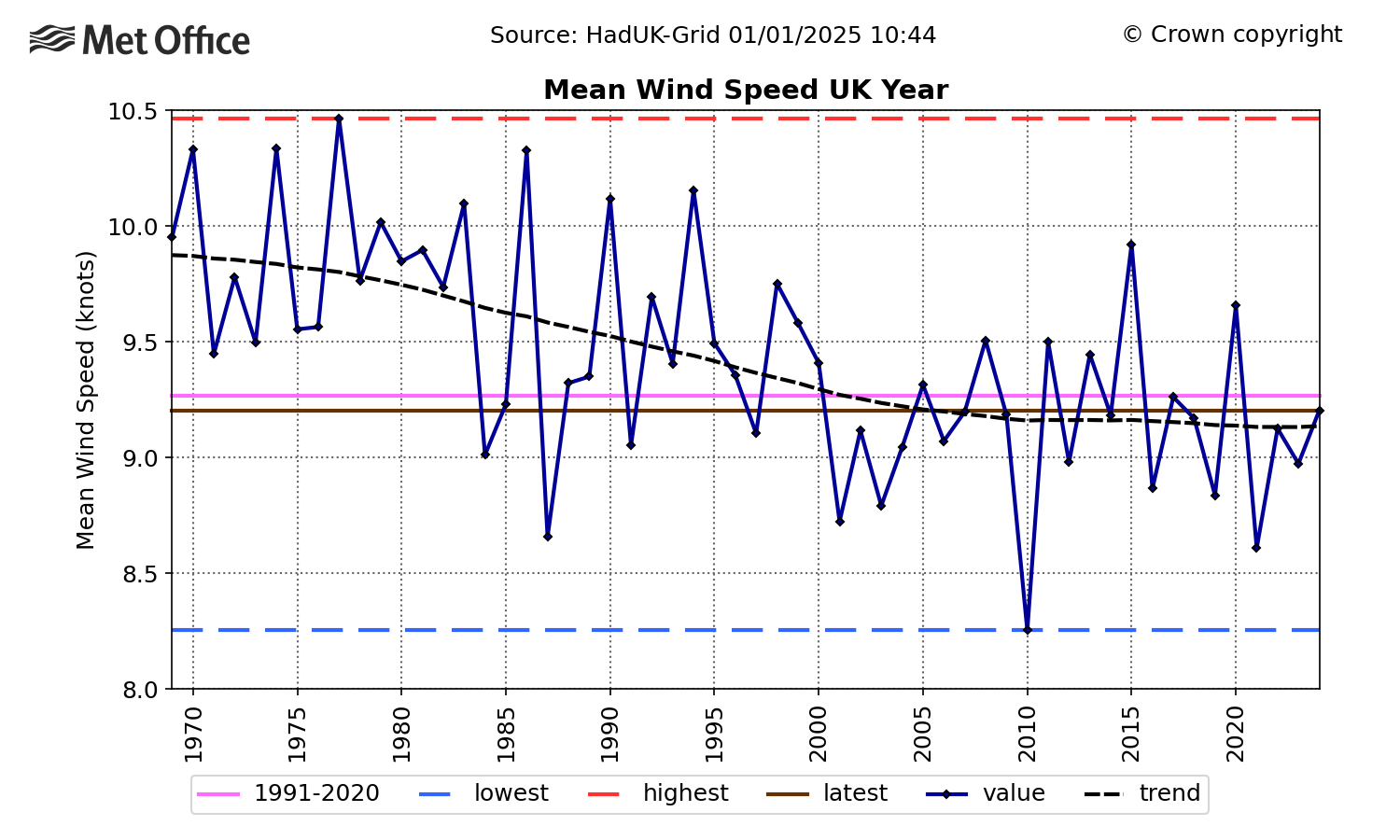

Overall, the average wind speed in 2024 was close to, but slightly below, the 1991-2020 average, while being the highest since 2020. This aligns with a long-term decline in the average wind speed for the UK since 1969, shown in the chart below.

This long-term trend should be interpreted with some caution as it is possible that non-climatic factors – such as changes in instrumentation and exposure of the observing network through time – influences these trends. However, the decline is consistent with a widespread global slowdown termed “global stilling”.

More recently, global and UK data have shown that, since 2010, the decline in the average wind speed has stopped or even reversed.

Winter

The climatological UK winter spans the calendar months of December, January and February. Winter 2023-24 was mild and the fifth warmest on record for the UK. For England and Wales combined it was the second warmest on record.

The year commenced with some significant flooding impacts from storm Henk, which brought damaging winds and heavy rain to central and southern England and Wales on 2 January. The rain fell on already saturated ground, leading to flood warnings. High pressure became more established from mid-January, bringing a spell of cooler and drier conditions. The month concluded with storms Isha and Jocelyn in quick succession.

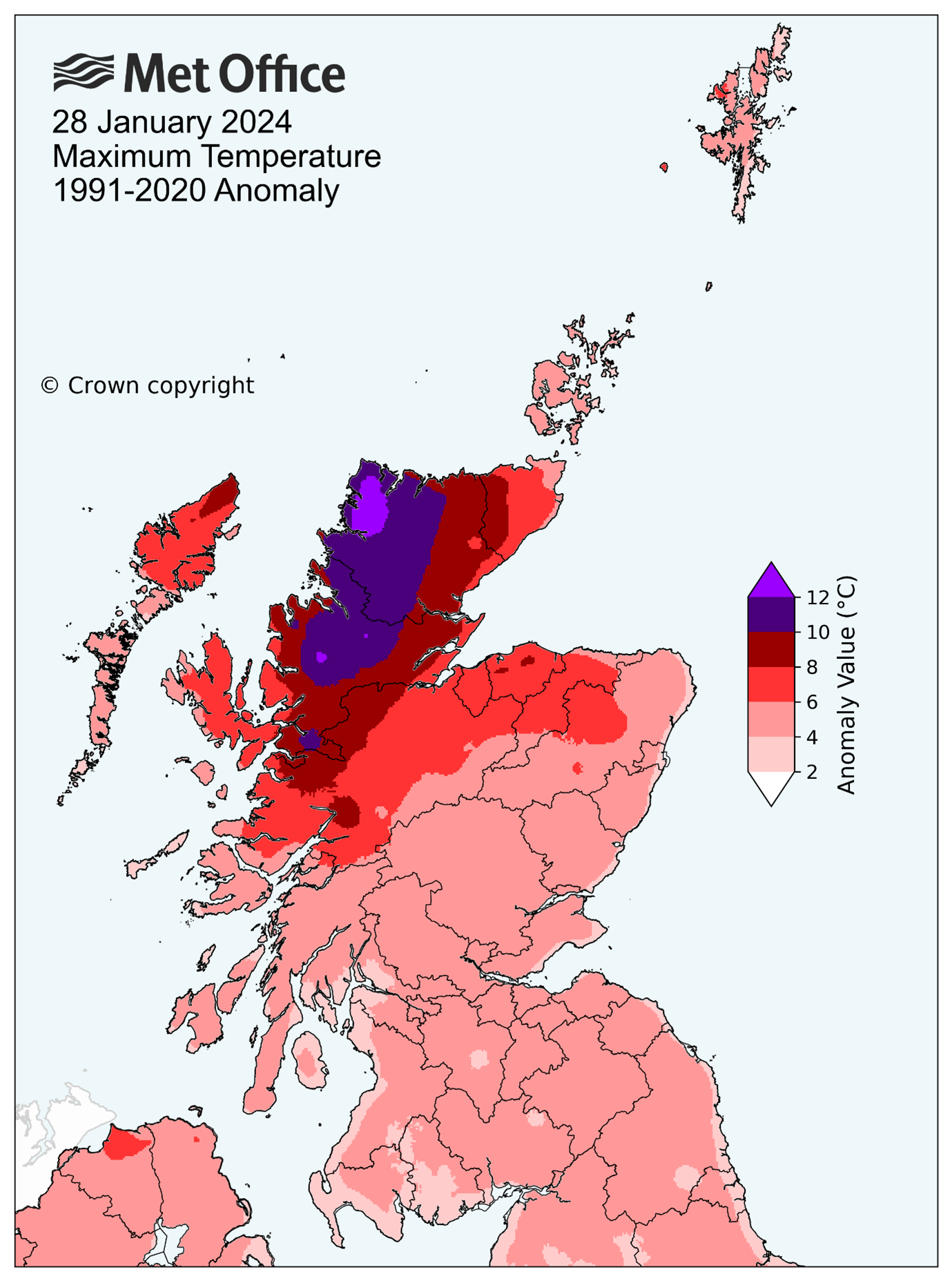

On 28 January, exceptionally high temperatures for the time of year were recorded in parts of north-west Scotland, reaching 19.9C at Achfary and 19.6C at Kinlochewe, surpassing both stations’ previous record of 18.3C by a large margin. There was a marked contrast between cooler and more moist conditions on the windward side of the highlands, and warmer, drier conditions on the leeward side.

This is the classic consequence of the Foehn effect, which can result in remarkably unseasonable temperatures locally due to the air losing moisture as it passes up and over the higher ground, resulting in warmer drier conditions when it descends.

The Foehn effect was the primary driver of January’s exceptional temperatures. However, it is worth acknowledging that global warming has led to high temperature records across all seasons in recent years. New maximum temperature records were set for January in 2024, February in 2019, July in 2022, October in 2011, November in 2015 and December in 2019.

In other words, new temperature records have been set for six of the 12 months of the year since 2011. Conversely, no months have set new lowest minimum records.

It was the warmest February on record for both England and Wales, and the second warmest for the UK overall. The years 2019, 2022, 2023 and 2024 also had warm Februaries which ranked in the top 10 warmest on record.

Meanwhile, the south of England has its wettest February on record, and England its fourth wettest. This resulted in widespread disruption, particularly to transport, due to flooding and landslips.

Overall, it was the eighth-wettest winter for the UK, continuing a trend of wetter winters consistent with climate projections that indicate that human-caused climate change will drive a shift to wetter winters.

Spring

The year 2024 saw the warmest May, and spring, on record for the UK.

It was also the sixth wettest spring on record, after a succession of low-pressure systems brought rain to much of the country, with the exception of north-west Scotland, which was drier than average.

The preponderance of wet weather contributed to considerable surprise – and in some cases disbelief – of the extent to which May broke its all-time temperature record. The possible disconnect between the recorded temperatures and perception of the conditions was also due to extreme daily minimum temperatures occurring overnight. An exceptionally warm month in spring does not necessarily mean a month of fine and dry weather.

A Met Office analysis of the May 2024 event demonstrated that a significant contributing factor to the high temperatures was from a marine heatwave affecting the waters around the UK for the whole of May and early June. Although the UK was under cloudy skies for much of May, clearer skies coupled with weak winds and wave conditions over the North Sea contributed to very high sea temperatures.

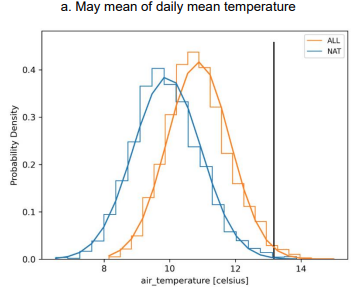

In addition to the contribution from the marine heatwave, a Met Office attribution analysis also found that human-induced climate change made the May average temperature between six and 14 times more likely than it would have been in a pre-industrial climate. The chart below shows how the likelihood of temperatures at or exceeding May 2024 are lower in a natural – or pre-industrial – climate compared to one impacted by human activities.

Summer

The summer was arguably rather disappointing for many, with warm spells generally being short-lived and the season being cooler than average overall, and the coolest summer since 2015.

Although July was wetter than average for parts of the country, both June and August were relatively dry for most. Western Scotland and parts of north-west England were the exception and were notably wet in August, with some areas receiving more than 200% of average rainfall for the month. It was the third-wettest August on record for western Scotland.

A short hot spell across central and southern England on 11-12 August saw the highest temperature of the year, of 34.8C in Cambridge. This was followed – as is often the case in the breakdown of summer heat events – with an outbreak of thunderstorms. These particularly affected northern and western parts of the UK.

Storm Lilian in late August resulted in high winds and rain with significant disruption to road, rail and power supply across northern England. Storm Lilian means that the 2023-24 season has had the most named storms since the naming system was launched 10 years ago.

The storm naming system is designed for raising awareness of the potential of risk to life and property from extreme storms. The decision to name considers both the severity of the storm and also its likelihood to cause impacts. For example, a storm system passing over heavily populated regions coinciding with rush hour in the summer months when trees are in full leaf can carry higher risks than a storm of the same wind severity passing through overnight in winter.

Storm naming criteria and the partners involved have evolved over time. For these reasons the number of named storms over time cannot itself be used as an indicator of change.

Autumn and December

Autumn continued the rainy theme. A succession of low-pressure systems throughout September resulted in some exceptional rainfall for southern and central England, with more than 300% of average rainfall observed across a wide region.

It was the seventh-wettest September for England and the wettest September on record for 10 counties in central and southern England. For Bedfordshire and Oxfordshire, September was the wettest calendar month the counties have experienced in a series dating back to 1836. Meanwhile, the Oxford Radcliffe meteorological station recorded its wettest month since September 1774.

The remainder of autumn saw the first named storms for the 2024-25 season: Ashley in October and Bert and Conall in November. Storm Bert brought heavy rain and snow.

The day of 21 November saw the most significant November snow event since 2010, with lying snow as far south as Devon and Cornwall. This was one of the coldest spells of weather in the year, although lower temperatures were recorded during the January cold snap earlier that year. The spell was short-lived and conditions were much milder again throughout December. It was the fifth-warmest December in a series dating back to 1884.

December was also notable for a red weather warning issued for storm Darragh for west Wales and the Bristol Channel, with extreme wind gusts along exposed coastal and upland areas. Some of the strongest winds were from an unusual northerly direction, likely influencing the number of fallen trees. A number of fatalities were reported and more than 2 million people were left without power during the storm.

The weather of the UK within any single year is diverse and at times surprising, and 2024 was no different. Where records have been broken, they have been for exceptionally high temperatures and high rainfall totals. This is another reminder that climate change is already having an impact on the UK’s weather, shifting the probabilities to make high temperature extremes and records increasingly likely to be broken and re-broken.

The drivers of rainfall records are more complex, but climate projections have consistently pointed to a general pattern of wetter winters, drier summers and more intense rainfall when it occurs. It is therefore vital to continue to monitor the indicators of change both globally and in the UK, in order to better understand what changes can be expected in the future, and how to respond to climate-related risks.