Met Office: A review of the UK’s climate in 2023

Multiple Authors

01.12.24The year of 2023 was the second-warmest on record for the UK, narrowly behind the record set as recently as 2022.

It was also the warmest year on record for Wales and Northern Ireland, second-warmest for England and third-warmest for Scotland.

In this review, we look back at the UK’s climate in 2023, the significant climate events that shaped the year and how human-caused climate change influenced them. We find:

- Eight of the 12 months of the year were warmer than average.

- Somewhat unusually, the warmest periods were in June and September, with the high summer months of July and August generally cooler and wetter.

- June was the hottest month of the year for the first time since 1966 and was the hottest June on record by a large margin.

- Through a climate attribution analysis, we show that a year as warm as 2023 has been made around 150 times more likely due to human-caused climate change.

- We would expect to reach or exceed the 2023 annual temperature in around 33% of years in the current climate.

- 2023 was relatively wet with 1,290mm of rainfall, making it the UK’s 11th wettest year in a series going back to 1836.

- The few wintery cold spells of the year were relatively short-lived.

- 2023-24 has seen the most active start to the storm season since naming storms began in 2015.

(See our previous annual analysis for 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019 and 2018.)

The year in summary

The Met Office produces the HadUK-Grid dataset for monitoring the UK climate. Using geostatistical methods, we combine UK observational data from land-based stations across the country into a gridded, geographically complete dataset.

There is enough coverage of observational data in our digital archives for national coverage of monthly temperature since 1884, rainfall since 1836 and sunshine since 1910. These are used to define long-running climate series and climatological averages, which provide context for variability and change in the UK’s climate through time.

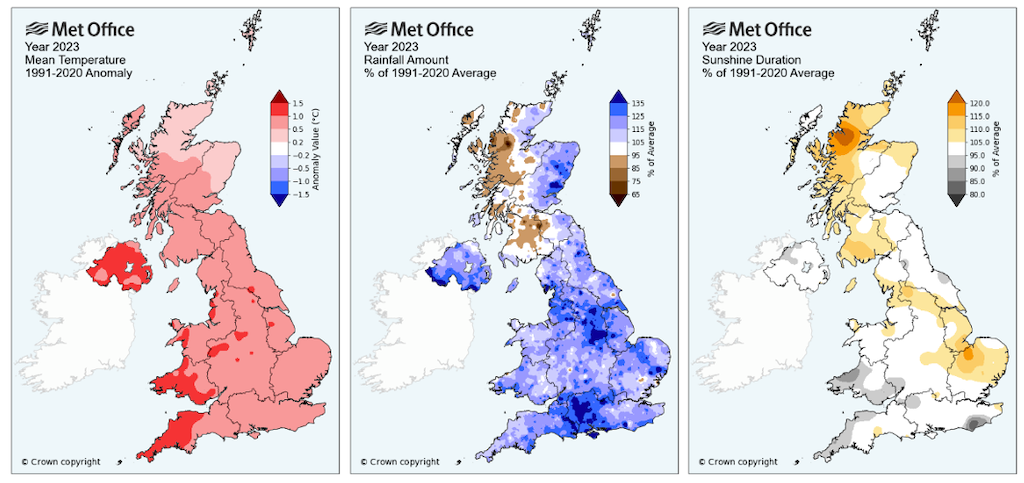

The maps below show the average anomalies compared to 1991-2020 for temperature (left), rainfall (middle) and sunshine duration (right) across the UK during 2023. The darkest shading shows the areas of the country that saw the warmest (red), driest (brown) and sunniest (yellow) conditions relative to the baseline climate.

The maps show that 2023 was, for most of the country, a warm and wet year compared to average, with close to average sunshine overall. The exception to this being western Scotland which saw drier and sunnier conditions.

The UK annual average temperature was 9.97C for 2023, which is just 0.06C below the record high of 10.03C in 2022. This continues an observed warming of the UK climate since the 1960s.

The hottest year in the UK during the whole of the 20th century was 1997, with an average temperature of 9.41C. So far in the 21st century, 13 years have exceeded this value, meaning that the majority of years so far in the 21st century have exceeded what was the hottest year of the 20th century.

In contrast, the coldest year of the 21st century so far was 2010 (7.94C) which was more than 0.5C warmer than the coldest year of the 20th century in 1963 (7.40C).

While 2010 is an extreme-cold year in the context of the current UK climate, it would have been much closer to the average for the late 19th and early 20th century. Climate change has significantly reduced the occurrence and severity of cooler conditions in the UK.

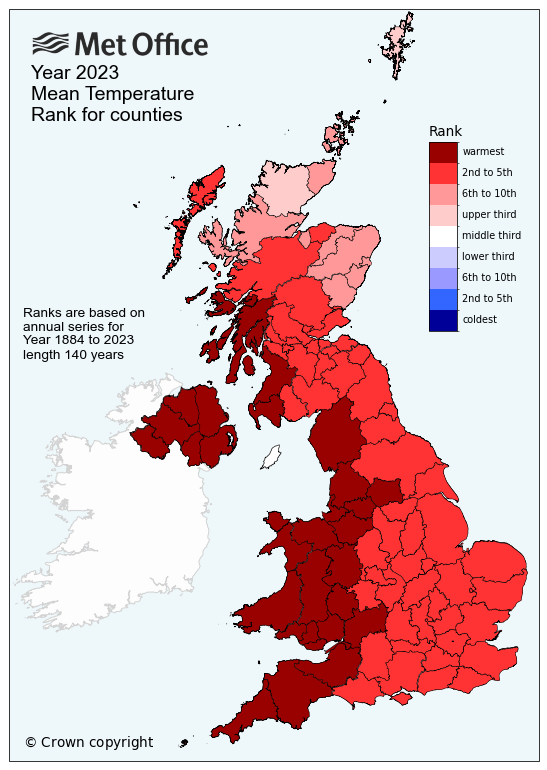

Looking regionally, the map below colour-codes UK counties by the ranking of annual average temperature.

The darkest shade of red identifies those counties that recorded their warmest year in 2023. It was the warmest year on record for all of Northern Ireland and Wales, and also for counties in western England and south-west Scotland.

The year 2022 retains the record for the majority of England and Scotland, with the exception of far north Scotland (for which the warmest year on record was 2014), Western Isles (2006), Orkney (2003) and Shetland (2014).

In addition, 2023 is also provisionally the warmest year on record for Ireland in the 124 year national series maintained by Met Eireann.

Central England Temperature record

The year of 2023 was also the second-warmest year in the Met Office Central England Temperature series (CET), marginally behind 2022. The CET represents a region bounded by Hertfordshire, Worcestershire and Lancashire.

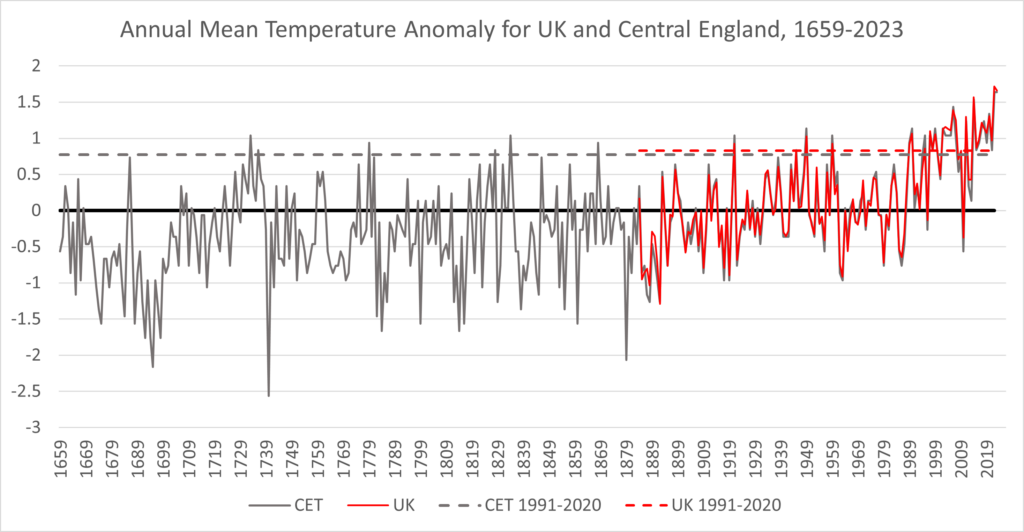

The chart below compares the records for the CET (black) and whole UK (red) for annual average temperature.

While there are inevitable differences in the precise ranking and anomalies of individual years between UK and CET, the series show the strong overall level of agreement. It also highlights how unusual the temperature of 2022 and 2023 are in the context of more than 360 years of observational data.

Extremes and rainfall

The UK climate monitoring network records both daily maximum and daily minimum temperatures.

Last year was the record highest for the annual average daily minimum temperature for the UK, England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and fourth highest for Scotland.

It was the highest annual average daily maximum temperature for Northern Ireland, second-highest for the UK, England and Wales, and third-highest for Scotland.

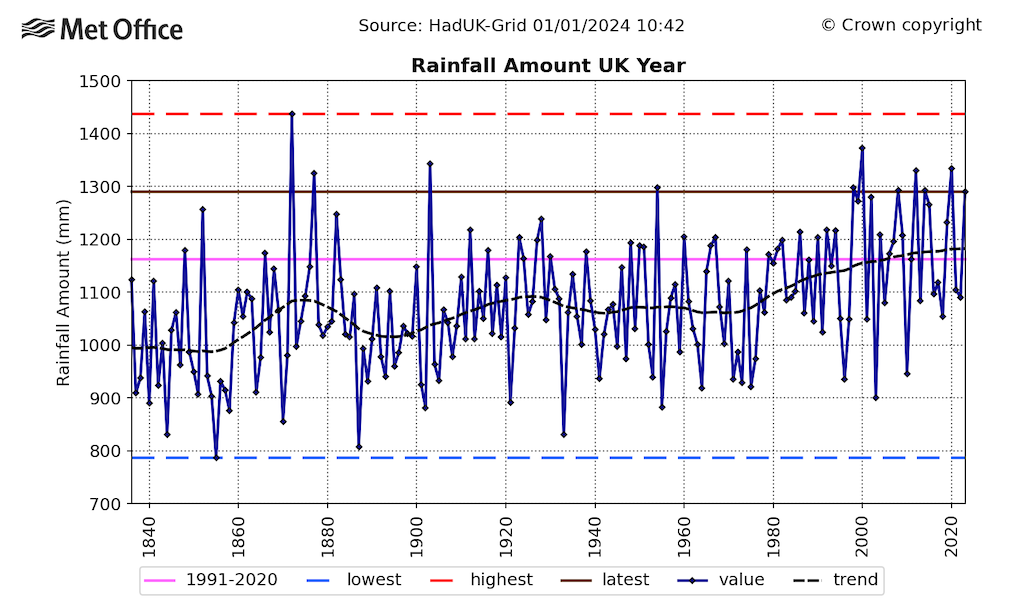

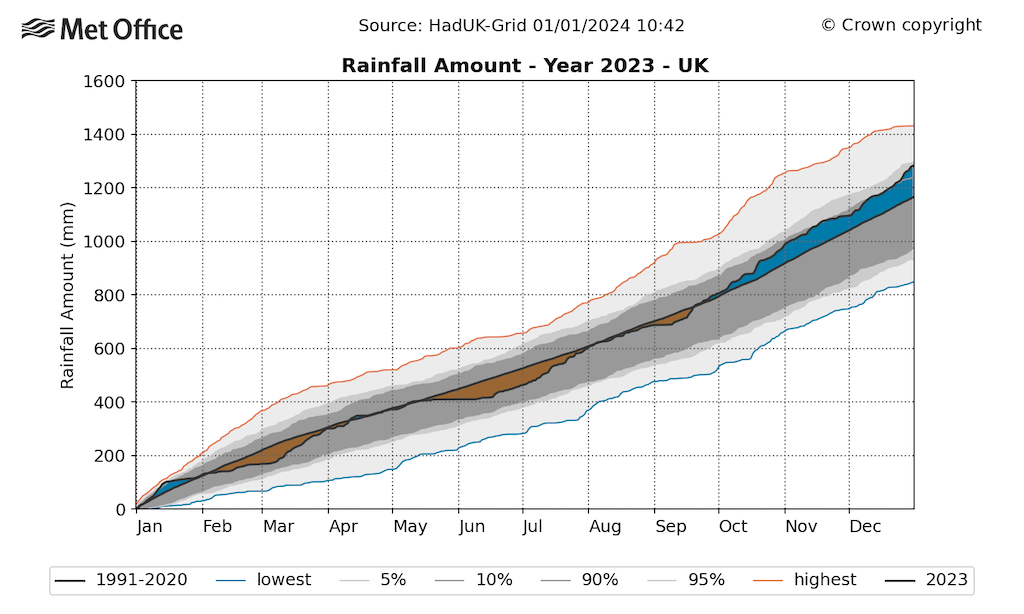

The year of 2023 was relatively wet with 1,290mm of rainfall, equivalent to 111% of UK average rainfall and putting it just outside the top 10 as the 11th wettest year in a series going back to 1836.

It was the sixth wettest March and July, seventh wettest October and ninth wettest December. In addition, 2023 is the only year that has four individual months within the top 10 wettest on record for the respective month.

The wet spells of March and July followed dry spells during February and June, but it was the higher-than-average rainfall through the autumn and into December that pushed up the annual accumulation for the year overall.

As the chart below shows, there has been an observed increase in UK annual rainfall over recent decades, with 2023 joining a cluster of notably wet years that have occurred since the late 1990s.

The lines show the annual rainfall (dark blue) and trend (black dashes), along with the 1991-2020 average (pink), 2023 total (brown) and the highest (red dashes) and lowest (blue dashes) annual totals on record.

The drivers of annual rainfall trends are complex as the annual total masks distribution of rainfall throughout the year and will respond to a multitude of factors, which will include human-caused climate change but also contributions from natural climate variability.

Attribution of UK annual mean temperature in 2023

Met Office scientists conducted an attribution study to quantify the influence of human-caused climate change on the likelihood of reaching a UK annual average temperature at or above that recorded in 2023.

The method uses an established Met Office system for rapid attribution of extreme events. The analysis uses observed values of the UK annual temperature and temperature data for the UK drawn from 14 climate model simulations from the sixth – and most recent – phase of the global Coupled Model Intercomparison Project.

The models are evaluated against the observational data across the period 1884-2014 using approaches commonly adopted for attribution studies. This determines whether they are suitable for use in the assessment and provide adequate representations of UK annual average temperature trends and variability.

One set of model simulations uses only natural climate forcings (“NAT”) for the period 1850-2020, while another set uses all natural and human-caused forcings (“ALL”) for the historical period and the SSP2-4.5 emissions scenario, often described as a “medium” emissions scenario, out to 2100.

These simulations are then able to provide estimates of the likelihood of the UK annual temperature exceeding the observed 2023 value for the following scenarios:

- A natural climate without human-caused greenhouse gases.

- The current climate taken as a 20-year period centred on 2023.

- An end-of-century climate under a medium emissions scenario taken as the period 2081-2100.

A reference baseline for all the experiments is the period 1901-30.

The estimated return period for a UK annual average temperature exceeding 9.97C in the NAT simulations is once every 460 years (with a range of 82 to 587). For the ALL simulations in the present day, this drops to once every three years (with a range of 2.86 to 3.17). For the ALL simulations in the future, this falls further and could see temperatures warmer than 2023 being exceeded more frequently than every other year.

Human-caused climate change is, therefore, estimated to have increased the likelihood of a year as warm as 2023 by a factor of more than 150.

These results are, unsurprisingly, very similar to an equivalent study conducted a year ago in relation to the record-breaking annual mean temperature of 10.03C set in 2022. Regarding that study, we stated:

“A warming climate means that an event that would have been exceptionally unlikely in the past has become one that we will increasingly see in the coming decades.”

Importantly, this analysis also indicates that 2022 and 2023 are not necessarily that extreme in the context of our current climate. This means that there is the potential for a far higher UK annual average temperature extreme even in the present-day climate. In addition, by the end of the 21st century, most years will be warmer than 2023.

Weather through the year

Temperature

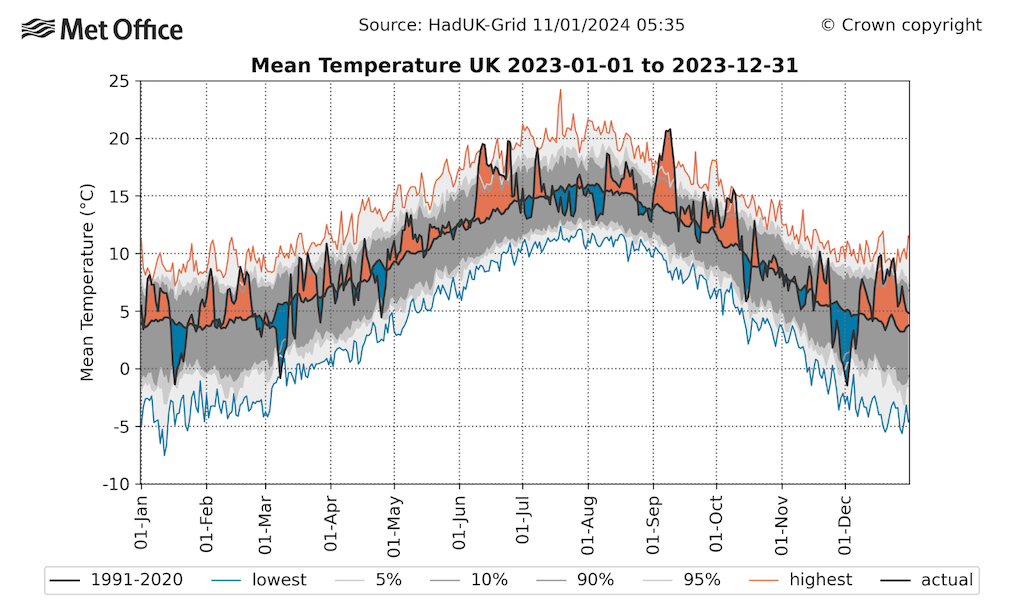

The chart below tracks UK average temperatures through the year, with orange highlighting periods that were warmer than the 1991-2020 average for the time of year and blue were cooler than average.

Overall, 66% of days (240 days) were warmer than the 1991-2020 average for the time of year and 34% (125 days) were colder. The most notable warm spells were in June, September and December.

The highest maximum temperature of the year was 33.5C at Faversham (Kent) on 10 September, which is only the fifth time a highest maximum has been recorded in September. This is equal to the 1991-2020 average annual maximum temperature, so it is close to what we would expect as the highest UK temperature for a typical year. However, it is 2.3C higher than the average maximum during the earlier period of 1961-90 (31.2C).

In September, there was also a run of seven consecutive days with temperatures somewhere in the UK exceeding 30C, which is the longest such run in September on record.

The lowest temperature of the year was -16.0C, recorded at Altnaharra (Sutherland) on 9 March during a spell of wintry weather. This is 0.5C below the 1991-2020 average (-15.5C), but 3C above the 1961-90 average (-19.0C) for the year’s coldest day.

In 2023, both the hottest and coldest weather of the year occurred outside of the climatological summer and winter season, a reminder of the variable nature of the UK climate.

Both the highest maximum and lowest minimum temperature of the year for the UK have been increasing at a faster rate than the UK average temperature, reflecting that heat extremes are becoming more severe while cold extremes are becoming less severe in our warming climate.

Rainfall

For rainfall, the wettest periods were seen in March, July, October and December.

In the chart below, the rainfall accumulation is tracked through the course of the year. The solid black line is the 1991-2020 average, the grey shading reflects the variability across years with the red and blue marking the highest and lowest on record. Brown shading highlights points in the year where the total rainfall since the start of the year was below average, and blue regions are where it is above average.

The chart highlights that a dry spell in February was compensated by the wet March, and the dry spell through May and June was followed by a wet July, returning the year to near-average by the start of autumn.

Western Scotland was an exception to this rainfall pattern, with a somewhat drier autumn in particular, although wetter conditions in the east, including some extreme rainfall such as during storm Babet in October, meant that Scotland overall was still wetter than average. For England it was the sixth wettest year on record, third wettest for Northern Ireland, 12th for Wales and 32nd for Scotland.

Storms

The Met Office storm naming, first launched in 2015, provides a storm name list for the period from 1 September to 31 August each year in collaboration with Met Eireann and KNMI, the Irish and Dutch national weather services, respectively.

The 2022-23 storm season was rather notable for the relative absence of storms, with the only storms to be named under this scheme both occurring right at the end of the season in August – storms Antoni (5 August) and Betty (18-19 August).

In contrast, the 2023-24 season has experienced a much more active start with seven named storms from September to December, and the eighth (storm Henk) in early January 2024, which is the most active start to the named storm season since its inception in 2015.

| Storm Name | Dates affected UK | Maximum wind gust | Number of observing sites recording wind gusts over 50 knots |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022-23 names | |||

| Otto | 17 February (named by Danish Meteorological Service) | 72 Kt (83mph) Inverbervie, Kincardineshire | 31 |

| Noa | 12 April (named by Meteo-France) | 83 Kt (96mph) Needles, Isle of Wight | 25 |

| Antoni | 5 August | 68 Kt (78mph) Berry Head, Devon | 2 |

| Betty | 18-19 August | 57 Kt (66mph) Capel Curig, Conwy | 5 |

| 2023-24 names | |||

| Agnes | 27-28 September | 73 Kt (84mph) Capel Curig, Conwy | 15 |

| Babet | 18-21 October | 67 Kt (77mph) Inverbervie, Kincardineshire | 16 |

| Ciarán | 1-2 November | 68 Kt (77mph) Langdon Bay, Kent | 11 |

| Debi | 13 November | 67 Kt (77mph) Aberdaron, Gwynedd | 21 |

| Elin | 9 December | 70 Kt (81mph) Capel Curig, Conwy | 13 |

| Fergus | 10 December | 64 Kt (74mph) Aberdaron, Gwynedd | 11 |

| Gerrit | 27-28 December | 77 Kt (89mph) Fair Isle, Shetland | 42 |

| Henk | 2 January 2024 | 82 Kt (94mph) Needles, Isle of Wight | 35 |

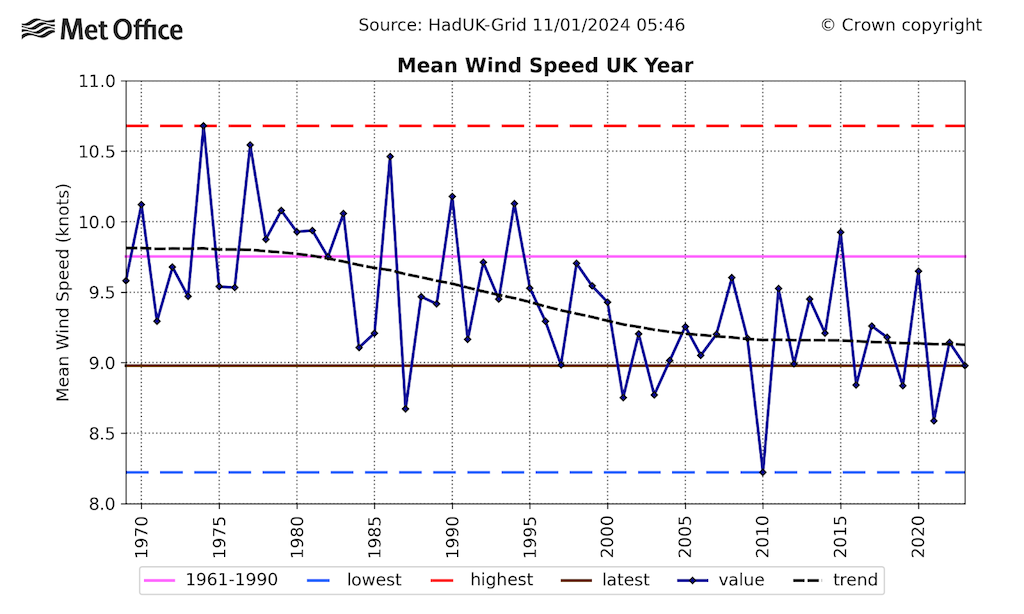

Overall, 2023 was calmer than average. This reflects a long-term decline in average wind speed, as illustrated in the chart below. This shows average UK wind speeds for each year since 1969 (dark blue line), the trend (black dashes), 1991-2020 average (pink), 2023 total (brown) and the highest (red dashes) and lowest (blue dashes) annual averages on record.

This long-term trend should be interpreted with some caution as it is possible that changes in instrumentation and exposure of the observing network through time may influence these trends. However, the decline is consistent with a widespread global slowdown termed “global stilling”.

More recently, global and UK data have shown that since 2010 the decline has stopped or even reversed.

Winter

After a notably wet spell at the start of the year – resulting in flooding across south Wales and Midlands on the 12 January – the late winter period was characterised by a very sunny January and very dry February overall.

It was the driest February since 1993 with much of central and southern England, which received less than 20% of the normal monthly rainfall.

The climatological winter season (1 December 2022 to 28 February 2023) was drier than average and – as discussed above – relatively calm with just one named storm (Otto) occurring in an otherwise dry February.

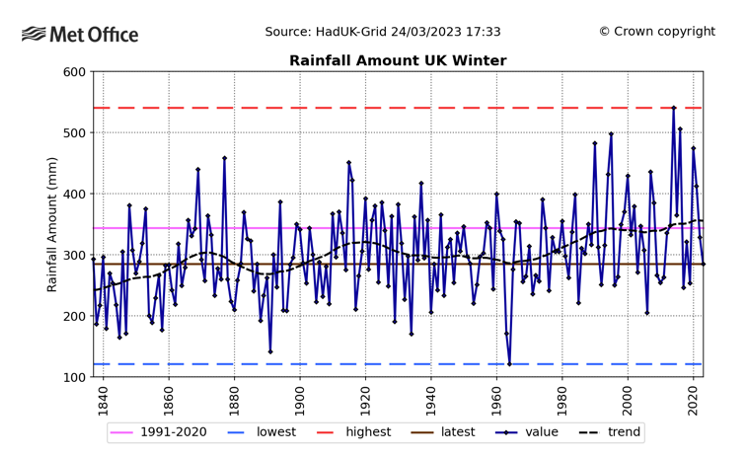

The chart below depicts UK winter rainfall per year (dark blue line) since 1836. While 2023 was relatively, but not exceptionally, dry in the context of recent decades, it is closer to the average for earlier in the series. The winter of 2022-23 had 83% of the 1991-2020 average rainfall, but 94% compared to the earlier period of 1961-90.

Comparing 1991-2020 to 1961-90, winter rainfall for the UK has risen by 14%. The increase is not uniform across the UK, however, with the greatest increases in excess of 20% across north and west Scotland, and smaller rises below 10% for central and southern England.

It is notable that, in a series stretching back to 1836, the five wettest winters have all occurred since 1990. The record wettest winter of 2013-14 had approximately double the rainfall of 2023, highlighting the large interannual variability in UK rainfall.

In contrast, at the time of writing, wet weather through the first half of the 2023-24 winter has resulted in widespread flooding across the country.

Climate variability is a critical driver in recent extremes of winter rainfall, while the emerging climate change signal resulting from increased moisture in the atmosphere is an important secondary factor contributing to the risk of wetter winters.

UK climate projections indicate a clear shift to higher probability of wet winters over the UK. This is caused by an increase in the number of wet days, an increase in intensity of rainfall, and a decrease in the proportion of winter precipitation falling as snow.

Spring

The first half of March was generally cold and resulted in some of the lowest temperatures of the year.

By the middle of the month, the situation became milder and wetter. March was exceptionally wet for many regions except for northern Scotland. It was the sixth-wettest March for the UK, third-wettest for England and Northern Ireland and fifth-wettest for Wales.

April saw temperature and rainfall statistics near-average, although Storm Noa was one of the most significant April storms since 2013, with hundreds of homes across south-west England and Wales left without power.

A maximum wind gust of 83 Kt (96mph) at Needles on the Isle of Wight was the highest wind gust on record for England during the month of April. This particular site is located at the top of a cliff exposed to westerly winds so is representative of a very exposed coastal location. Inland winds were lower, but still sufficient to cause some disruption.

May was warmer and drier overall, although heavy thunderstorms over 7-11 May caused surface-water flooding across parts of southern and eastern England. Drier weather from the middle of the month, however, resulted in a shift to wildfire reports across parts of Wales, the south-west and west Yorkshire by the end of the month.

Summer

It was the warmest June on record for the UK with an average temperature of 15.8C, beating the previous record of 14.9C that was set in the Junes of 1940 and 1976 by 0.9C. Previously, the top three warmest Junes were separated by just 0.1C.

The highest daily temperature reached in the month was 32.2C (on 10 and 25 June), which did not challenge the June temperature record of 35.6C, recorded on 28 June 1976. What was unusual about June 2023 was the persistence of the warmth rather than its severity. Temperatures exceeded 25C for at least a fortnight with peaks in excess of 30C.

A long-standing curious statistical quirk of UK climatology was that 13 June was the only June date that had never previously recorded temperatures in excess of 30C in meteorological records spanning over 100 years. This quirky fact was finally broken this year, reaching 30.8C on 13 June.

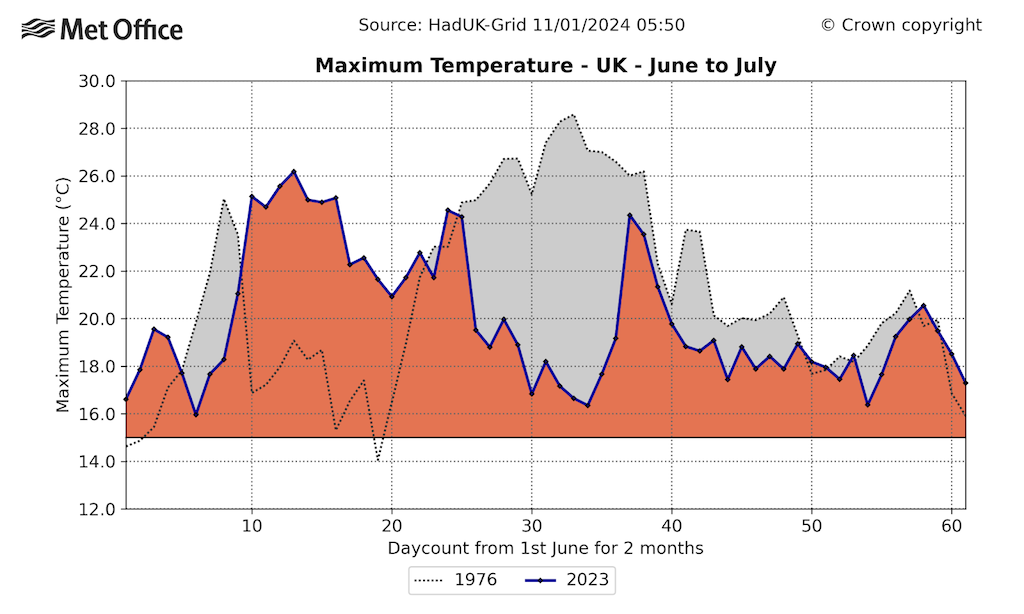

The chart below shows a comparison of the 2023 June heatwave with 1976, the previous joint record warmest June. This shows the UK-average daily maximum temperature through June and July for 1976 (dotted line and grey shading) and 2023 (blue line and orange shading).

The 1976 heatwave was certainly more severe than 2023, but occurred slightly later in the season, peaking in early July. In contrast, the persistent warmth in 2023 fell within the calendar month of June.

A significant contributing factor to the exceptional and persistent warmth was a major North Atlantic marine heatwave, which brought record-breaking temperatures in the North Atlantic and around the UK. A severe marine heatwave was declared in mid-June, which further amplified temperatures over the UK land.

An attribution study by the Met Office found that the likelihood of beating the UK land June temperature record had at least doubled compared to when it was first set in 1940. We estimated there was around a 3% chance of beating the record in a 1991-2020 climate and, by the 2050s, a record could be occurring around every other year on average under a high-emissions scenario.

Unsurprisingly, the June warmth was associated with a persistent high-pressure system resulting in plenty of clear skies and dry conditions. The month was, therefore, also the fourth sunniest June on record, and the sunniest June since 1957, but not as sunny as the exceptionally sunny month of May 2020.

Some more unsettled weather at the end of the month meant that while recording only around 68% of average rainfall, June was not dry enough to trouble any records.

A more unsettled situation then took over for the remainder of the summer, with conditions turning cooler, duller and windier.

It was the sixth-wettest July on record with 140.1mm and the wettest since 2009 (145.5mm). It was the wettest July on record for Northern Ireland and for parts of north-west England including Merseyside, Lancashire and Greater Manchester.

August continued the unsettled theme with a distinct lack of summery weather – however, it was not as wet as July.

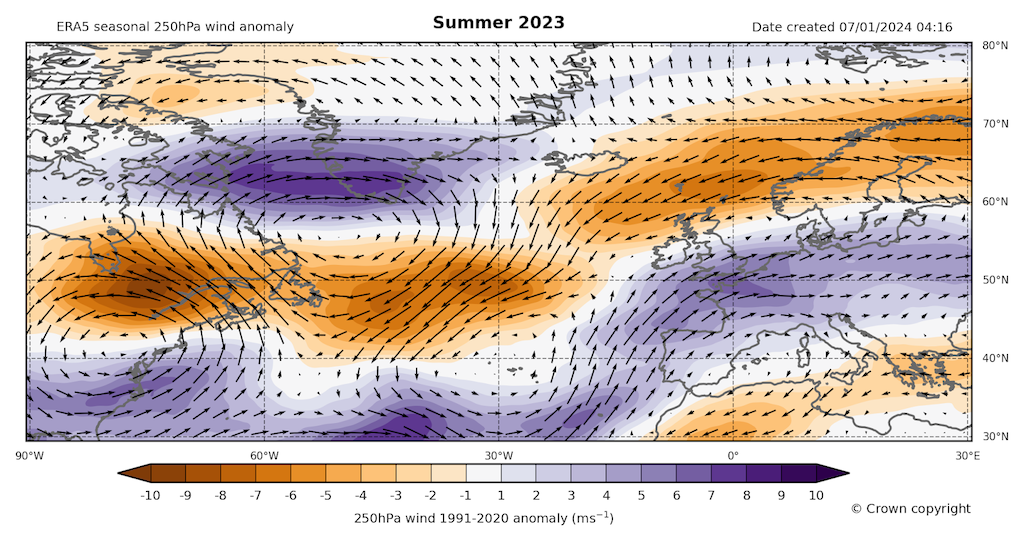

A key driver of the wet high summer was a displacement in the jet stream to a more southerly track across the UK. The map below shows anomalies in wind speed at 250hPa, relative to a 1991-2020 average. (250hPa is a level of equal pressure and is equivalent to a height of around 10.5km.)

The purple regions show where the wind is stronger than average and orange they are weaker – highlighting a strengthening of the upper-level wind across southern England and a weakening in the more typical summer jet stream to the north of Scotland. This resulted in low-pressure weather systems from the Atlantic being directed on a more southerly track over the UK.

Despite being relatively wet during the high summer (July through August), the average temperature averaged across July (14.9C) and August (15.3C) was 15.1C. This was cooler than June (15.8C), but close to the 1991-2020 average for Jul-Aug (15.2C).

Another indicator of the influence of climate change on UK climate is that a wet summer such as that of 2023 is approximately 1C warmer than equivalently wet summers from the past.

Autumn (and December)

In early September, the jet stream shifted north and high pressure returned. Consequently, the UK experienced another heatwave bringing some of the hottest weather of the year, peaking at 33.5C at Faversham, Kent on 10 September.

A new high-temperature record was also set for the month for Northern Ireland with 28C at Castlederg, County Tyrone on the 8 September.

It was the longest run of days reaching 30C somewhere in the country during September on record at seven consecutive days (4-10 September). It is only the fourth time on record that the highest temperature of the year has occurred in September, with the other years being 2016, 1954, 1949 and 1919. High temperatures were not confined to the daytime and some locations also recorded “tropical nights” when the minimum temperatures do not drop below 20C.

The month concluded with Storm Agnes kicking off the 2023-24 storm season. But the early warmth contributed to it becoming the joint-warmest September on record for the UK (with 2006). An average temperature of 15.2C was warmer than July and only marginally behind August.

A rapid attribution conducted at the time showed that a September this warm would be exceptionally unlikely in a natural climate, but in our current climate there is approximately a 3% chance of reaching or exceeding it. A September this warm does still require the right combination of factors, but climate change is making such late-season warmth more likely.

The remainder of the autumn season and December continued the generally mild, wet and – at times – stormy theme, with the joint-sixth wettest October and joint-eighth wettest December on record. It was the sixth-warmest autumn for the UK and third-warmest for both England and Wales.

Reviewing 2023 demonstrates how the UK is subject to the combined influences of the variability in the weather, but also the influence of human-caused climate change. This is affecting both our climate statistics and also the likelihood of some types of extreme events.