Media response to 2022 IPCC report suggests shift to ‘solutions-based reporting’

Cecilia Keating

02.07.25Cecilia Keating

07.02.2025 | 1:25pmJournalists covering a major climate report in 2022 broke with a “historical tradition” of focusing on the negative impacts of climate change, shifting instead to “positive, solutions-based reporting”, a study has found.

The research, published in Climatic Change, looks at the way US and UK news outlets covered the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) 2022 report on the mitigation of climate change.

The findings “strongly suggest a shift in emphasis” to climate solutions in climate-change reporting, the authors say.

They note that previous IPCC reports “did not receive such an overwhelmingly positive, and at times even optimistic, message”.

However, the response to the report was significantly less optimistic on social media, where popular posts were more likely to focus on a “sense of hopelessness” and the “dire” nature of the climate threat, the authors say.

The findings contribute to the growing literature on the changing nature of media coverage as climate impacts become more frequent and severe, and groups opposed to climate action shift tactics.

Priority messages

The research looks at the media response to the report published in April 2022 by the IPCC’s Working Group III (WG3), as part of the influential body’s sixth assessment report cycle (AR6). (See Carbon Brief’s in-depth coverage.)

The report provides an overview of the world’s progress on tackling greenhouse emissions, while also examining the different sources of emissions. It is one of three comprehensive scientific assessments published each five-to-seven year IPCC assessment cycle, alongside reports on the physical science basis for climate change and its impacts.

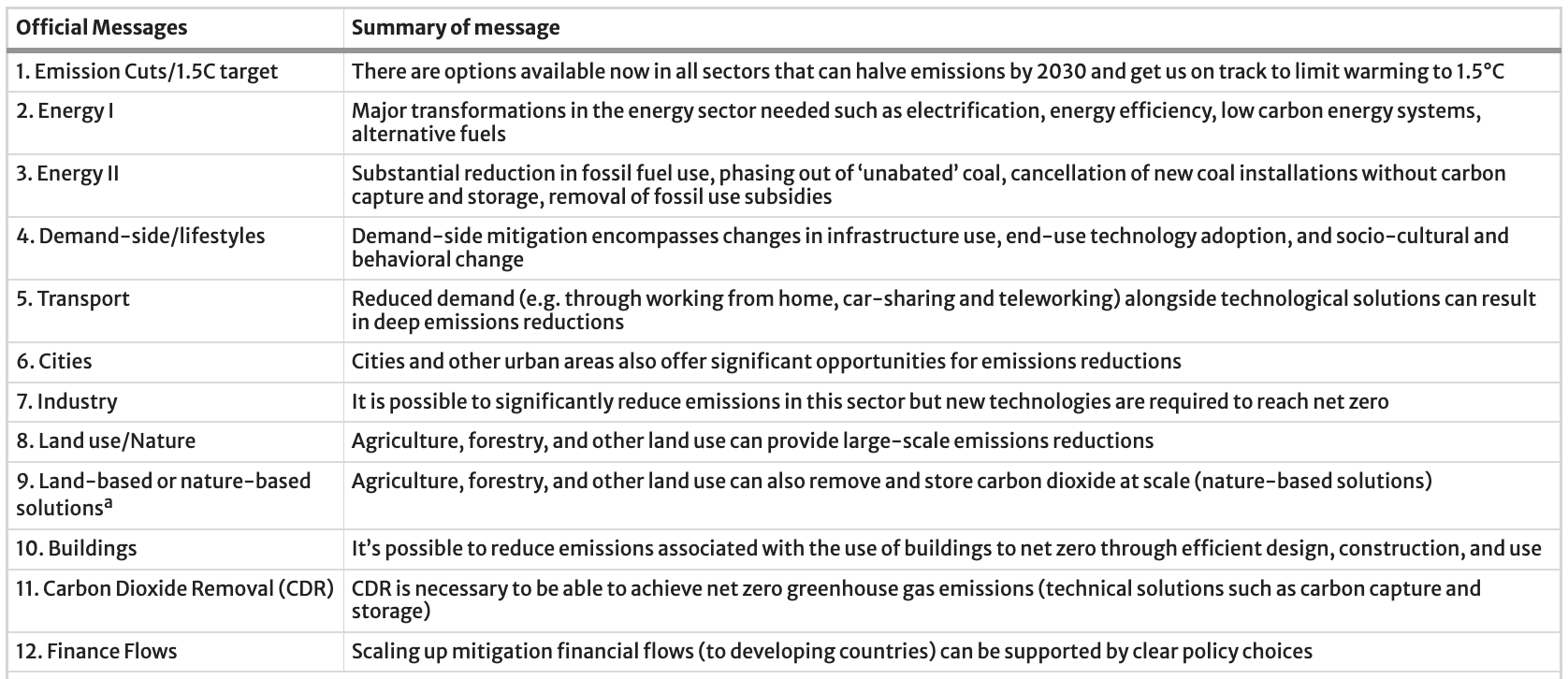

To assess the media’s response to the WG3 report, the researchers identify 12 “official priority messages” promoted by the IPCC around its launch.

These are based on the news release, the press conference, headline statements in the report’s summary for policymakers section, and social-media posts sent out by the IPCC’s communication team.

The table below sets out the IPCC’s key messages, as identified by the researchers, ranging from the headline “there are options available now in all sectors” to more specific messages around the need to decarbonise buildings and industry, and ramp up finance to developing countries.

The researchers then assess the presence (mentions) and dominance (inclusion in headline, top five sentences, or as a strong narrative throughout) of these “key messages” in 66 articles published over 4-6 April on more than 20 popular UK and US news websites.

They also look at how the 12 main messages aligned with 56 of the most popular social media posts about the report on Facebook and Twitter.

A small sample

The study’s media sample focuses on articles published by the top 12 most popular online news sites in the UK and US, as identified by Reuters Institute’s 2021 digital news report, with a few exceptions.

The sample features left-leaning publications, such as the Guardian and the New York Times, centre-right outlets, including the Times and the Financial Times, and right-leaning titles, such as the Daily Mail and the Wall Street Journal.

Regional newspapers and local television websites were missed due to a lack of coverage of the report.

The authors say they chose to focus on news media in the UK and US because the two countries are host to “legacy media organisations” that have a “strong worldwide presence in English (particularly online), host sceptical voices and are influential amongst policymakers outside of their home countries”.

The social-media sample includes posts by authors, news organisations, scientists, journalists and pro- and anti-climate action groups.

Dr James Painter – an author of the study and research associate at the University of Oxford’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism – tells Carbon Brief the sample size was relatively small largely due to a muted media response to the report. He adds:

“Sixty six [articles] isn’t a huge sample compared to other studies, but it is big enough to be robust and broad enough in terms of a spectrum of types of media outlets and political leaning.”

Solutions-focused coverage

The study notes that coverage “seldom deviated from the main messages the IPCC was promoting”.

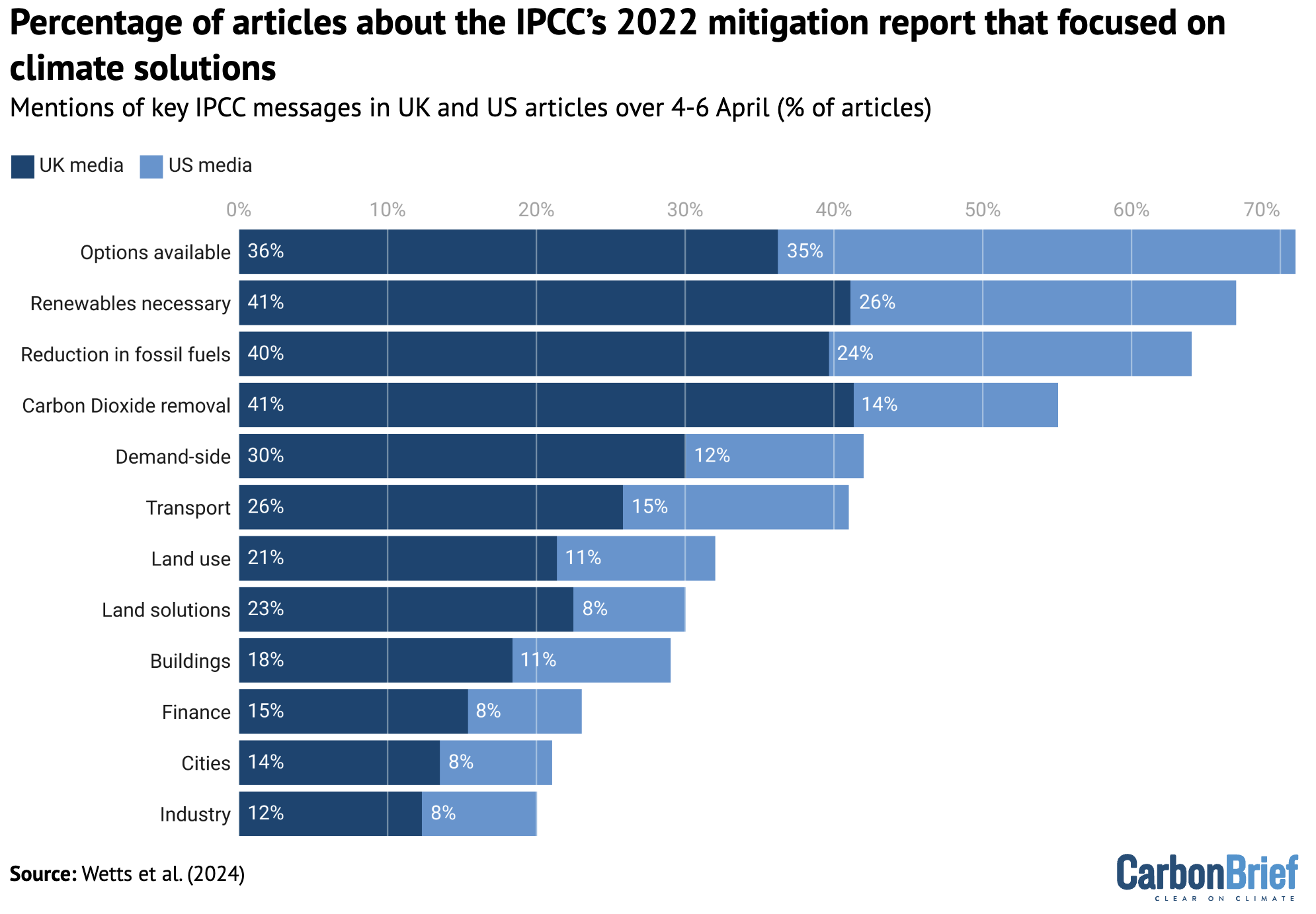

The three most mentioned messages are:

- “There are options available to reduce greenhouse gas emissions” (70%)

- “Major transformations in the energy sector are needed into renewables” (67%)

- “A substantial reduction in fossil fuels is needed” (63%)

A majority of articles (54%) also mention the IPCC’s recommendation that carbon dioxide removal (CDR) solutions are necessary to bring down emissions.

The bar chart below shows the percentage of UK and US media coverage that included the IPCC’s key messages, with UK media represented in dark blue and US media in light blue.

The authors say the paper provides a “detailed case study of which solutions get the most traction – and most critiques – in the media coverage of a policy event”.

For example, it notes how the least-mentioned solutions were sectoral measures focused on reducing the climate impact of industry, cities and buildings, and ramping up finance to poorer nations.

Painter says he believes the downgrading of these particular messages was a product of the space constraints of online journalism, which led journalists to prioritise “key findings” and “controversial” topics, such as CDR.

Break from the past

The research acknowledges that solutions-focused media coverage of the WG3 report is “to be expected”, given the document’s focus on climate mitigation options.

However, the researchers note that media coverage of the previous iteration of the WG3 report – published in 2014 – did not focus on solutions.

They point to a 2015 study that found the dominant frames of coverage were “settled science” and “political and ideological struggle”.

They also highlight analysis published in 2016 that finds a “low presence of the opportunity of action frame compared to disaster and uncertainty framing” in the response to all three key reports of the fifth IPCC assessment cycle.

As a result, the study authors argue the news media’s focus on solutions in reporting of the latest WG3 report “confirms a trend to more solutions coverage” observed by other researchers.

The research also notes the response to the 2022 WG3 report “to a large extent may have been prompted by the IPCC’s communication approach”.

However, Sigourney Luz, digital media and communications manager at Imperial College London and communications manager for the WG3 report, tells Carbon Brief that this is “difficult to determine”.

This shift could also be down to the nature of the report or “part of a broader trend in climate reporting”, she says, adding that “both media coverage of climate change and the scope of IPCC reports have evolved” between 2014 and 2022.

Dr Jill E Hopke, an associate professor of journalism at DePaul University, who was not involved in the study, says it is “encouraging” to see traditional media reflect the IPCC’s priorities. However, she adds that reporting of solutions remains scarce in reporting on climate impacts:

“The link is missing in that type of coverage, which is discouraging. As audiences and as people living on this planet, when we see extreme weather events driven by climate change, it is important to have media coverage that talks about the solutions relative, or links those things together.”

Dr Antal Wozniak, senior lecturer in media, politics and society at the University of Liverpool, who was also not involved in the study, adds that his research suggests that “solutions coverage now is actually shifting more towards adaptation [as opposed to mitigation], especially when you leave the politics beat”.

The pair are working on a number of studies which look at the media’s response to climate impacts, from heatwaves to soil degradation.

Social media

While traditional media narratives about the WG3 report largely dovetailed with the solutions-orientated messages promoted by the IPCC, social media posts did not.

The study finds that 60% of the social-media posts contained themes that did not reiterate any of the IPCC’s “official” or “unofficial” messages. Around half made no mention of solutions at all.

(On top of the 12 “official” IPCC messages, the researchers also looked at dominance and prevalence of three “unofficial messages” promoted by the IPCC and UN secretary general Antonio Guterres around the report launch – for instance, a warning that it was “now or never”.)

Instead, social-media posts focused on the “dire nature of the climate threat, the need for urgent action and a sense of hopelessness”, the study notes.

Painter says “strong” divergence between social media and news media responses holds implications for efforts to build momentum behind climate action:

“If there is an increasingly fractured debate where there isn’t consensus about responses to the climate challenge, then that is important. How do you build a sort of multi-sectoral alliance to do something about climate change if that is the case?”

Equity and justice

The study notes that the concepts of equity and justice “do not seem to have been given priority” by IPCC messaging, beyond a recommendation for more finance to go to poorer nations.

The message around financial flows was among the least covered by news media: it was the third-least prevalent message in mainstream media, and the fifth least dominant.

However, the research says that journalists highlighted issues of equity and justice that were not explicitly promoted by the IPCC. For example, it finds that 22% and 14% of articles, respectively, included messaging that either richer nations or wealthier individuals “should do more”.

The study also notes discussions of equity were “lacking” on social media, with just one social-media post – from Carbon Brief’s Simon Evans – focusing on the unequal distribution of greenhouse gas emissions within and between nations.

Climate obstructionism

Another notable finding of the media analysis was the absence of a response to WG3 from what the report authors dub the “organised climate counter-movement”.

This was contrary to expectations that the analysis might confirm a trend of changing tactics of climate-sceptic groups away from outright climate denial and towards questioning climate solutions.

In fact, the paper notes that the most common source cited in critiques of climate solutions in articles was the IPCC itself.

CDR technology was the most critiqued solution, with more than a third (35%) of articles raising some form of concern.

The authors note that the UK news media was “noticeably more critical of CDR and land-based solutions than the US sample”. The US media, on the other hand, was more critical of messaging around “options being available” and the need to phase out fossil fuels.

Overall, the study finds that the IPCC was the source for 57% of all critiques of solutions in the media studied, followed by the article authors themselves (23%), IPCC-affiliated and other scientists (15%), and pro-climate action campaign groups (5%).

In contrast, the research finds “only very limited presence of organised or individual scepticism on social media” and “no presence of evidence scepticism…nor any presence of organised scepticism or individual scepticism” in articles.

The researchers argue the relative lack of a response from sceptics could be a result of the study’s small sample size and a lack of specific country-level policy recommendations for groups to critique.

Dr Max Boykoff, a professor in the University of Colorado Boulder’s environmental studies department, who was not involved in the study, says the findings chime with his research into the evolving strategies of the Heartland Institute, which found the influential US conservative thinktank was increasingly preoccupied with opposing climate action at a state-level. He tells Carbon Brief:

“There was less of a focus on the international and national scene, and more of a focus on state level, local level engagements. In baseball lingo…it’s thinking about ‘small ball’, instead of trying to hit a home run.”

Boykoff adds that the study forms “part of a larger set of efforts that take place across research communities that add value to how we understand how the world is changing around us and what we can do to influence positive change”.

Wetts, R., Painter, J. & Loy, L. (2024) The IPCC in the hybrid public sphere: divergent responses to climate mitigation solutions in mainstream and social media, Climatic Change, doi:10.1007/s10584-024-03827-x

-

Media response to 2022 IPCC report suggests shift to ‘solutions-based reporting’