Media reaction: The 2025 Los Angeles wildfires and the role of climate change

Multiple Authors

01.13.25More than a dozen wildfires have been sweeping through Los Angeles in California, consuming tens of thousands of acres of land and devastating some of the wealthiest neighbourhoods in the US.

As firefighters battle to contain the blazes, at least 24 people have died, while tens of thousands of people have been forced to evacuate and thousands of properties have been razed to the ground.

The disaster has received widespread attention across international media, covering the scale of the damage through to the causes of the fires – and the political spats they have triggered.

Both US president Joe Biden and his Californian vice-president Kamala Harris made the link between climate change and the fires.

Meanwhile, many scientists have pointed to “climate whiplash” – rapid switches from wet to dry conditions that are becoming more common in a warmer climate – as a factor in the scale of the devastation.

Many outlets have highlighted misleading claims by right-wing commentators about the Los Angeles fire department, as well as statements from incoming president Donald Trump casting blame on California’s Democratic governor, Gavin Newsom.

A number of outlets have also explored the impact of the wildfires – which have already been dubbed the costliest in US history – on the state’s already-fragile property insurance market.

In this article, Carbon Brief examines the role of climate change in the Los Angeles wildfires and how the media has covered the disaster.

- How did the wildfires develop around Los Angeles?

- How were the fires ignited?

- What have been the impacts of the fires?

- Does climate change have a role in driving the fires?

- What has been the political reaction?

- How has the media responded to the wildfires?

- What are the implications for insurance in the state?

How did the wildfires develop around Los Angeles?

Over the course of just a week in early January, multiple fires erupted in and around Los Angeles in southern California.

The first – and what became the largest – wildfire was the Palisades fire. This was first reported at around 10:30am on Tuesday 7 January and quickly spread, explained the Washington Post, “as winds gust[ed] to about 50 mph in the area”.

The Financial Times reported that more than 29,000 acres [11,174 hectares] were burned on Tuesday in Palisades, “an affluent coastal community with some of the most expensive property in the US”. With thousands of homes at risk, evacuation orders were issued for around 30,000 people, according to the newspaper.

Rescuers were “forced to use a bulldozer to clear a path” through gridlocked, abandoned cars for emergency services to pass, reported the Times.

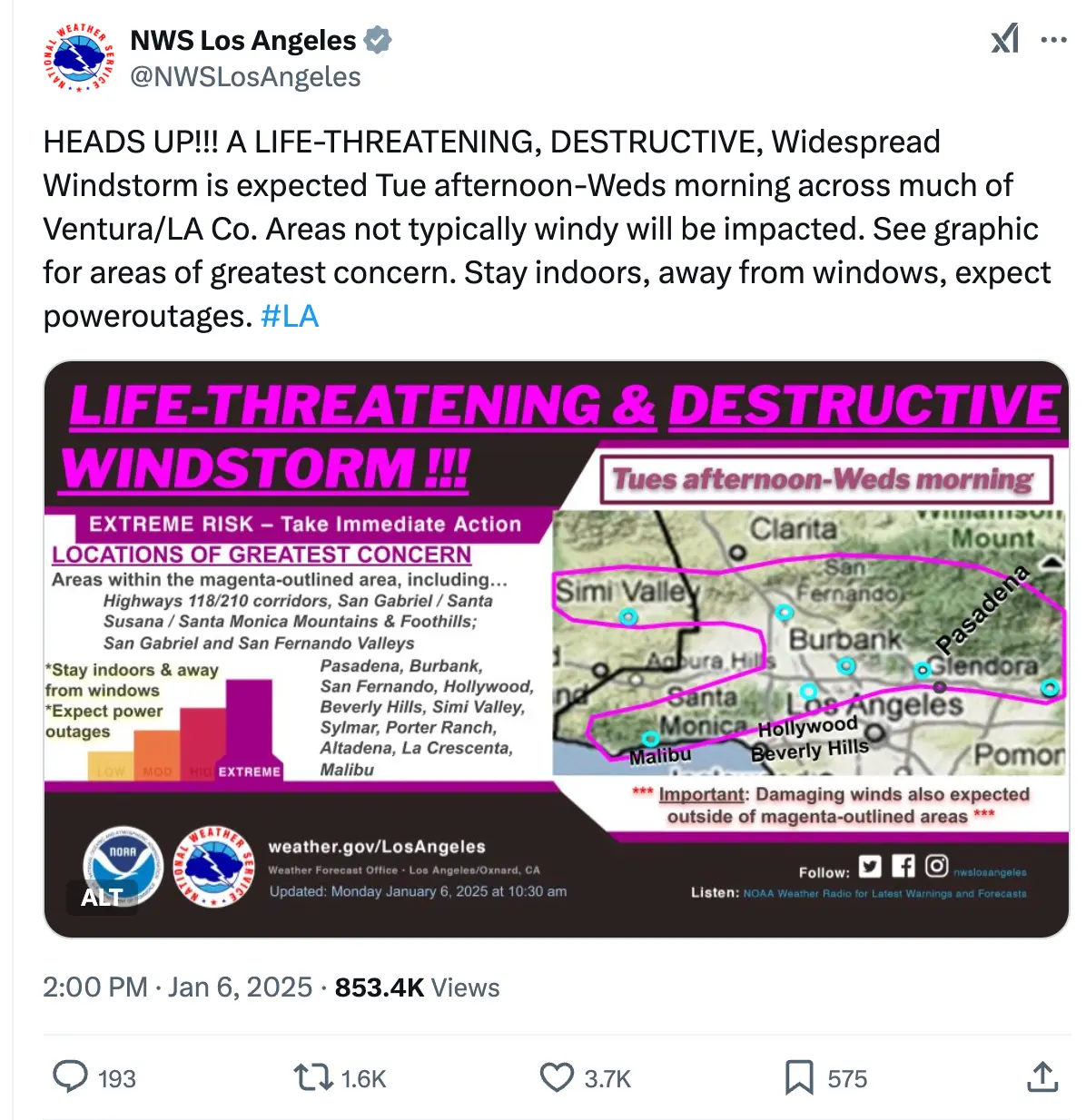

Through the day, a “life-threatening” windstorm “accelerated the fire’s spread across a parched landscape that has had very little rain in months”, the FT said. This storm was the “strongest to hit southern California in more than a decade”, the Associated Press noted.

An AP photographer reported seeing “multi-million dollar mansions on fire as helicopters overhead dropped water loads”.

The Washington Post described the Palisades fire as a “monster from the start”, noting that it spanned “the size of 150 football fields within half an hour and an area larger than Manhattan a day after that”.

On Tuesday night, a fast-moving fire broke out in the hills above Altadena near Eaton Canyon, reported the Los Angeles Times, prompting further evacuation orders.

The Eaton fire had “quickly grown to 200 acres” [81 hectares] by Tuesday night, said the Times, while “another fire had ignited in Sylmar, a suburb north-west of Los Angeles, and had already consumed 50 acres [20 hectares] with some nearby residents ordered to evacuate”.

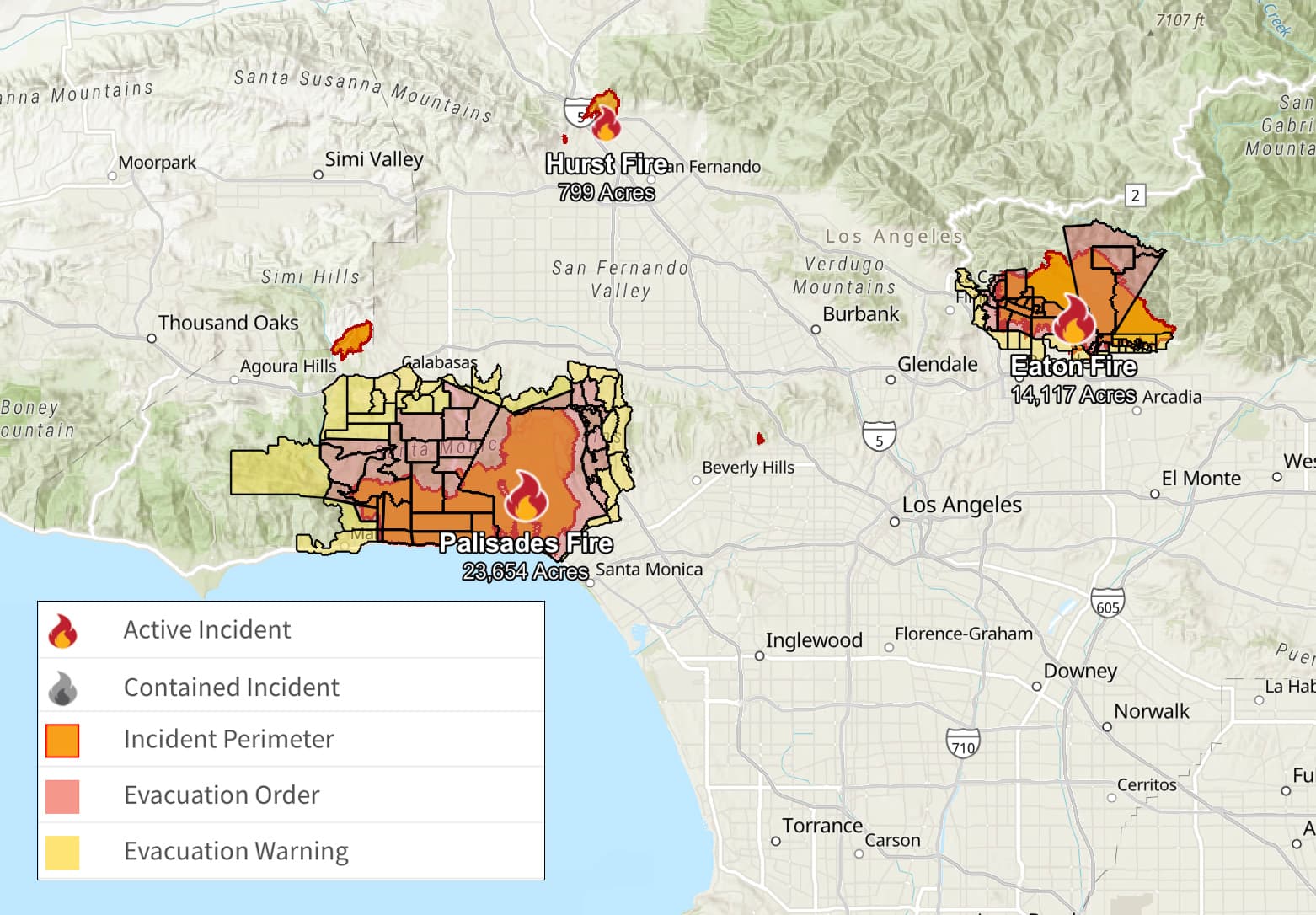

These three fires – Palisade, Eaton and what would later be named the Hurst fire – would become the focus of media coverage, but a number of other fires, such as Kenneth, Archer, Sunset, Lidia, Woodley and Olivas, also ignited across the region through the week.

By Tuesday evening, California governor Gavin Newsom had declared a state of emergency, CBS News reported.

On Wednesday, the wildfires “burned uncontrollably across a wide swathe of greater Los Angeles”, reported the Washington Post, “transforming the landscape into scenes of apocalyptic destruction with blocks and blocks of neighborhoods reduced to ash”.

By the end of the day, more than 1,000 structures had been destroyed, at least 130,000 people were under evacuation orders and nearly 1.5 million residents were without power, the newspaper said. The fires were still raging with “almost zero containment”, it added.

The newspaper quoted Los Angeles county fire chief Anthony Marrone, who warned that his department was prepared for one or two major fires, but not for “this type of widespread disaster”. He added:

“There are not enough firefighters in LA county to address…fires of this magnitude.”

In response, firefighting teams from across California and the west “poured into the Los Angeles region in recent days to help relieve and reinforce local crews”, said the Washington Post.

Reports also emerged that firefighters were, in the words of BBC News, “struggl[ing] with water supply to their hoses and hydrants”. Reuters noted that “Los Angeles authorities said their municipal water systems were working effectively but they were designed for an urban environment, not for tackling wildfires”.

In total, at least a dozen fires have raged across the greater Los Angeles area over the past week. By Friday, the two largest fires of Palisades and Eaton were 8% and 3% contained, respectively, reported the Los Angeles Times. This increased to 11% and 15% by Saturday morning.

More heavy winds are expected as the crisis enters its second week, prompting fears of further spread of fires. The Guardian reported that the US National Weather Service issued a rare “particularly dangerous situation” warning for Monday night into Tuesday morning. Bloomberg, the Hill and Politico also reported on the risks brought by increased winds.

This came after a local fire chief told BBC News that the fight against the blazes is “at a fork in the road”, warning that the fires could “take off on Tuesday or Wednesday”.

How were the fires ignited?

Investigators are still exploring the initial cause of the fires, reported the Associated Press.

While lightning is the “most common source of fires in the US…investigators were able to rule that out quickly”, the newswire said. It explained:

“There were no reports of lightning in the Palisades area or the terrain around the Eaton fire.”

The next two most-common causes are “fires intentionally set and those sparked by utility lines”, it added.

NBC News reported that the key to identifying the cause of the Palisades fire lies “on a brush-covered hilltop where the blaze broke out just after 10:30am on Tuesday”. A former battalion chief for the Los Angeles Fire Department told the outlet that arson was an unlikely cause:

“This is what we call inaccessible, rugged terrain…Arsonists usually aren’t going to go 500 feet off a trailhead through trees and brush, set a fire and then run away.”

Analysis by the Washington Post suggested the cause was an extinguished fire from New Year’s Eve. Combining photos, videos, satellite imagery, radio communications and interviews, the newspaper concluded that “the new fire started in the vicinity of the old fire, raising the possibility that the New Year’s Eve fire was reignited, which can occur in windy conditions”.

The Daily Mail picked up the Washington Post’s reporting, describing it as a “haunting new theory”.

Other fires, such as the Eaton fire, were linked to power lines, reported NBC News (link above):

“Whipping winds can cause the lines to slap together, shedding small balls of superhot molten metal.”

The Guardian noted that “it is routine for utilities to shut off power during ‘red-flag events’, but the power lines were on near the Eaton and Palisades fires” when they started last week.

However, NBC News said, this was just one theory, adding that “it’s also possible that it was started by a person operating a camping stove or a car or lawn mower that ejected a hot spark onto dry grass”.

Multiple lawsuits have been filed against Southern California Edison, claiming the utility’s equipment sparked the Eaton fire, according to the Washington Post.

What have been the impacts of the fires?

The fires that swept through Los Angeles have consumed more than 40,000 acres [16,187 hectares] of land, spread across a number of neighbourhoods in both the city and Los Angeles county, according to an update from the Washington Post on Monday 13 January.

The outlet also noted the fires had claimed the lives of 24 individuals at the latest count.

NPR added that more than 12,000 structures, including houses and businesses, had been destroyed by the fires over seven days.

In a separate article, the Washington Post mapped the wildfires in various areas in Los Angeles – Palisades, Eaton and Hurst. It noted that, as of 12 January, the Lidia, Sunset, Woodley, Archer and Kenneth fires had been contained.

In response to the fires, evacuation orders were issued for approximately 153,000 people in LA county, NBC Los Angeles reported.

The New York Times added that some evacuees found temporary housing in Los Angeles hotels, including a luxury hotel in Santa Monica and 19 hotels owned by the IHG chain, which includes Intercontinental, Regent and Holiday Inn.

Evacuations were ordered in “many parts of Pacific Palisades, Malibu, Santa Monica, Calabasas, Brentwood and Encino”, Los Angeles Times reported. Meanwhile, in areas including Glenoaks Canyon and Chevy Chase Canyon, evacuation orders were lifted, allowing residents to return to their homes, according to the outlet.

However, due to poor air quality affecting regions not directly impacted by the fires, schools in Los Angeles were cancelled on Friday, according to NBC Los Angeles. “Nearly all LA unified [school district] campuses and all offices would reopen Monday”, the Los Angeles Times added.

Cultural events have also been impacted, with the nominations for the 97th Academy Awards, and the Critics’ Choice Awards being postponed, as well as television shows such as Grey’s Anatomy and Jimmy Kimmel Live!, as reported by ABC News.

Meanwhile, an early estimate of total damages by weather forecasting service AccuWeather, widely cited in the media, including BBC News, predicts the fires have caused $135-150bn in total damages.

On Monday 13 January, the private forecaster increased its estimate of the cost of damages to $250-$275bn, as reported by the Guardian and others.

The fires are expected to have a major impact on California’s property insurance market. (See: What are the implications for insurance in Los Angeles?)

Does climate change have a role in driving the fires?

The severity and likelihood of wildfires are affected by a wide range of conditions. Some of these are related to the climate, such as temperature, wind speed and rainfall. Meanwhile, others are linked to land use, such as the density and type of vegetation, or human-implemented fire-suppression techniques.

Nevertheless, there is a wide body of evidence showing that climate change is making wildfire conditions more likely in many parts of the world. Attribution studies have revealed that climate change has already made many individual wildfires more intense or likely.

A rapid attribution study about the wildfires published on 13 January found that climate change was responsible for around 25% of the “fuel” available for the fires, according to CNN. Specifically, the research – carried out by scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles – focused on the extremely low moisture levels in dead vegetation following an “anomalously hot” summer and autumn. As a result, the researchers said, the fires “were larger and burned hotter than they would have in a world without planet-warming fossil fuel pollution”.

News outlets and experts across the world have been making the climate connection to the fires in recent days. Many outlets note that Los Angeles has seen rapid swings between extremely dry and wet conditions over the past few years.

BBC News reported that “decades of drought in California were followed by extremely heavy rainfall for two years in 2022 and 2023”, which allowed lots of vegetation to grow. However, the state saw a switch to very dry conditions in the autumn and winter of 2024, which dried out the vegetation, providing ideal fuel for the wildfire.

The outlet highlighted a timely academic paper, which explains that climate change has increased “hydroclimate whiplash” conditions – the rapid swings between periods of high and low rainfall – globally by 31-66% since the middle of the 20th century.

Dr Daniel Swain – a climate scientist from UCLA, who led the research – wrote a Bluesky thread explaining why climate “whiplash” can create the ideal conditions for fires to spread. He said:

“In coastal southern California, where grass and brush (including chaparral) are predominant vegetation types, there is actually a historical relationship between wetter winters and increased fire activity in [the] following fire season.”

Many outlets unpacked the rapid changes in California’s rainfall. The Guardian reported that in both the rainy seasons of 2023 and 2024, more than 25 inches of rain fell over southern California. However, it said this year’s rainy season “is running at just 2% of normal for Los Angeles, which has only seen 0.16in [4mm] of rain so far”.

Al Jazeera reported that, on 7 January, only 39% of California was completely drought-free, with the rest of the state described as “abnormally dry”. However, around the same time last year, 97% of the state was classed as “drought-free”, with only 3% classed as abnormally dry, it said.

Many outlets also pointed to the Santa Ana winds. According to the Guardian, these winds blow dry, warm air into California from the US western desert during cooler months, and have contributed to many forest fires in the past. The Associated Press reported that the winds were “much faster than normal” this year and have been “whipping flames and embers at 100mph”.

BBC News reported that the low-humidity Santa Ana wind “strips the vegetation of a lot of its moisture, meaning that fire can catch quicker and the vegetation burn more readily”.

Inside Climate News said the “unusually warm” band of the Pacific Ocean near southern California is bending the jet stream, allowing high pressure to settle over the north-east of Los Angeles, while intensifying the Santa Ana winds.

In the Conversation, Prof Jon Keelet from the University of California, Los Angeles, explained his research, which shows a shift in the timing of Santa Ana winds. “Due to well-documented trends in climate change, it is tempting to ascribe this to global warming, but, as yet, there is no substantial evidence of this,” he said.

What has been the political reaction?

As the fires blazed, US president Joe Biden met with California’s Democratic governor, Gavin Newsom, and approved his request for a major disaster declaration, enabling increased federal funding, according to the Los Angeles Times.

When asked by NBC News if he thought these fires would be the worst “natural” disaster in US history, Newsom replied: “I think it will be just in terms of just the costs associated.”

Craig Fugate, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) administrator under former president Barack Obama, told the Los Angeles Times that the fires were LA’s “Hurricane Katrina” – a moment that would “forever change the community”.

Bloomberg reported that Biden said federal support would cover 100% of the costs of the fire response for 180 days. The president also directed 400 additional federal firefighters and more than 30 helicopters and planes towards the region, the news outlet added.

Both Biden and his Californian vice-president Kamala Harris made the link between climate change and the fires in their public statements.

The wildfires come at a fraught political moment for the US. Biden, who has championed climate action during his presidency, will soon be replaced by Donald Trump, a climate sceptic who has vowed to roll back many of his predecessor’s policies.

Trump’s response to the fires was summarised in an Associated Press headline that stated: “As wildfires rage in LA, Trump doesn’t offer much sympathy. He’s casting blame.”

The article said Trump had taken aim at his “longtime political foe” and falsely blamed Newsom’s forest management policies and fish conservation efforts in California for the water shortages affecting the response effort . It added that Trump “has a history of withholding or delaying federal aid to punish his political enemies”.

The Los Angeles Times noted that both Biden and current FEMA administrator Deanne Criswell “stopped short” of guaranteeing that aid would continue under Trump.

Following the incoming president’s remarks, Newsom addressed a letter to Trump inviting him to visit LA fire victims and stating “we must not politicise human tragedy or spread disinformation”, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Leading Republicans in Congress have echoed Trump’s criticism of California’s leadership, calling for “conditions” and “strings attached” to any aid provided to the state, according to the Washington Post. The newspaper noted that this was not the norm, with “lawmakers typically approv[ing] federal aid after natural disasters without requiring states to change policies first”.

There were also claims in right-wing media that Democratic LA mayor Karen Bass had cut the fire department’s budget, but the Los Angeles Times noted that its budget “actually grew by more than 7%”. BBC News and Media Matters both ran articles fact-checking various claims made about Democrats by figures on the US right.

The Guardian reported on “misinformation” spread by the US right, including claims that the LA fire department prioritised “diversity schemes” – often referred to as “DEI” – over fighting fires. Elon Musk, Trump’s new “efficiency tsar”, supported such claims, and wrote on Twitter: “Wild theory: maybe, just maybe, the root cause wasn’t climate change?”

Meanwhile, another Guardian article noted that “nearby blue and red states as well as foreign countries are making their own political statements in their decisions to deploy firefighters to aid California”. CBS Austin reported that Republican Texas governor, Greg Abbott, has provided resources to California.

Canada and Mexico sent firefighters to help in California, with Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau offering his nation’s “full support”. Trump has threatened to impose punitive tariffs on both nations.

How has the media responded to the fires?

There has been extensive coverage in the media of the wildfires, across the US and around the world.

This has taken many forms, but there has been a particular focus in editorials on political divisions and the role of climate denial. For example, an editorial in the Guardian argued that “political obstruction is deepening a climate crisis that needs urgent action”.

In the Washington Post, columnist Jennifer Rubin said that the fires should affect the spread of climate denial, “but won’t”. She wrote:

“The hellish fires tearing through the Los Angeles area are a preview of what’s to come if politicians, ideologues and big oil continue to ignore climate change…These sorts of horror shows will become routine if climate change deniers, led by the [Make America Great Again] anti-science crowd, get their way.”

Explainers on the role of climate change in the Los Angeles wildfires have formed a notable part of the media reaction. This included pieces from the Associated Press, Al Jazeera, Channel 4 News, Le Monde, Axios and the Los Angeles Times, among others.

Elsewhere, right-leaning, climate-sceptic media has called into question the role of climate change and conservation on the wildfires. Many have also criticised the Democratic government of California, as well as the Los Angeles fire chief and members of her department.

In the Daily Telegraph, Freddy Gray, deputy editor of the Spectator, argued that “the LA fires are an epitaph for Democrat misrule”, hitting out at the “climate change lobby” and arguing that the Biden administration “spent far too much time and resources pursuing politically correct causes at the expense of competent or even sane governance”.

An article in the New York Post hit out at Los Angeles mayor Karen Bass’s “botched response” to the fires. It also amplified the comments made across social media by celebrities such as actor James Woods, who claimed that “the fire is not from ‘climate change’” and instead blamed “liberal idiots” for electing “liberal idiots like Gavin Newsom and Karen Bass”.

As noted in a piece in Forbes, Youtubers have been among the right-wing influencers pushing criticism of fire department policy. For example, journalist Megyn Kelly – recently dubbed the “Rumplestiltskin of irritation” in Vox – alleged that the fire chief “has made not filling the fire hydrants top priority, but diversity” in a viral clip.

Similar misleading claims have been made on social media, including by Twitter CEO and leader of the new US Department of Government Efficiency Elon Musk, who, as noted above, argued the Los Angeles fire department “prioritised [DEI] over saving lives and homes”.

In response to the misinformation and disinformation being spread, there has also been a wave of articles attempting to counter or factcheck claims. This includes articles in the Guardian, the Los Angeles Times, BBC News and the Times, among others.

One specific aspect of the coverage of the Los Angeles wildfires has been the impact on celebrities, with the homes of Billy Crystal, Paris Hilton and Eugene Levy destroyed in the fires. As such, there has been a range of coverage from sources for whom disasters would generally fall outside their remit, including Page Six, Hello!, Elle, TMZ and others.

An editorial in the Daily Mirror argued that “the destruction of celebrity mansions has captured attention, but we should not forget ordinary Americans”.

What are the implications for insurance in Los Angeles?

Media coverage has highlighted how the fires are set to deliver a major blow to the area’s property insurance market – seen as in “crisis” already – with major consequences for the Californian economy and households across the state.

Insured losses of the Los Angeles fires are expected to be in the tens of billions, according to early predictions from the insurance industry cited by Bloomberg and Reinsurance News.

The eye-watering damages are driven in part by Los Angeles’ expensive real estate. The National Post said the wildfires could prove to be “the costliest in US history, specifically because they have ripped through densely populated areas with higher end-properties”. Properties in the affected Palisades neighbourhood, for example, have a median home value of $3.1m, according to real-estate data cited in a CBS News report.

After wildfires in 2017 and 2018 decimated the industry’s profits, insurers have pulled back from California’s property insurance market in recent years, making it difficult for homeowners to find affordable cover. State Farm, Allstate and Farmers Insurance are among the insurers that have either dropped California policies or halted underwriting in recent years, CBS News said.

As a result, the Los Angeles Times said the fires threaten “to deepen a crisis that has already left hundreds of thousands of Californians struggling to find and keep affordable homeowners insurance”.

Meanwhile, the New Yorker said the “insurance crisis” has been “years in the making”, noting that people had been moving to wildfire-prone areas, despite fires “becoming more destructive, in large measure due to climate change”.

The retreat of insurers from California means a significant proportion of homeowners in Los Angeles rely on the state’s insurer of last resort, California’s Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) plan.

There are now concerns the FAIR plan – which is run by the state government, but pools funds from insurers – could run out of money, putting private insurance firms on the hook to foot the bill. These costs – which could be as large as $24bn, according to the San Francisco Chronicle – would likely be passed on to insurance policyholders across the state.

The New York Times said such a scenario “would further strain the financial health of those insurers, adding to the pressure to pull back from the [California property insurance] market”. It adds:

“The potential consequences are huge. Without insurance, banks won’t issue a mortgage; without a mortgage, most people can’t buy a home. Fewer buyers mean falling home prices, threatening the tax base of fire-prone communities. It’s a scenario that could come to define California, as rising temperatures and drier conditions caused by climate change intensify the risk of wildfires.”

The Los Angeles Times said rising insurance costs for homeowners were just one way the fires would exacerbate the region’s “housing affordability crisis”. The paper has also pointed to higher rents and fierce competition for contractors that can rebuild destroyed and damaged properties.

Euronews reported the financial losses of the fires would also impact European reinsurance companies, citing figures from analysts at investment bank Berenberg that calculated Swiss Re could face a loss of about €160m, Hannover Re a loss of €180m and Munich Re a loss worth approximately €220m.

The crisis comes as insurers around the world grapple with the rising costs attached to escalating climate impacts. Munich Re data – covered by Reuters – reveals that extreme weather events in 2024 caused an estimated $140bn in insured losses globally, up from $106bn the previous year.

Dave Jones, the former insurance commissioner of California and director of the Climate Risk Initiative at Berkeley School of Law, told Time the dynamics hurting California’s beleaguered insurance market could spread to other states as climate impacts intensified. He said:

“In the long term, we’re not doing enough to deal with the underlying driver, which is fossil fuels and greenhouse gas emissions, so we’re going to continue to see insurance unavailability throughout the US. We are marching steadily towards an uninsurable future in this country.”

Update: This article was updated to include the latest developments concerning the fire on 14/01/2025 and 17/01/2025.

-

Media reaction: The 2025 Los Angeles wildfires and the role of climate change