Mapped: How ‘natural’ world heritage sites are threatened by climate extremes

Ayesha Tandon

02.05.25Ayesha Tandon

05.02.2025 | 5:06pm“Natural” world heritage sites, such as the Galápagos Islands, Serengeti national park and Great Barrier Reef, could be exposed to multiple climate extremes by the end of the century, researchers warn.

The study, published in Communications Earth & Environment, assesses the impacts of extreme heat, rainfall and drought on 250 natural world heritage sites, under different emissions scenarios.

Natural world heritage sites are areas recognised by the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) for their “natural beauty or outstanding biodiversity, ecosystem and geological values”.

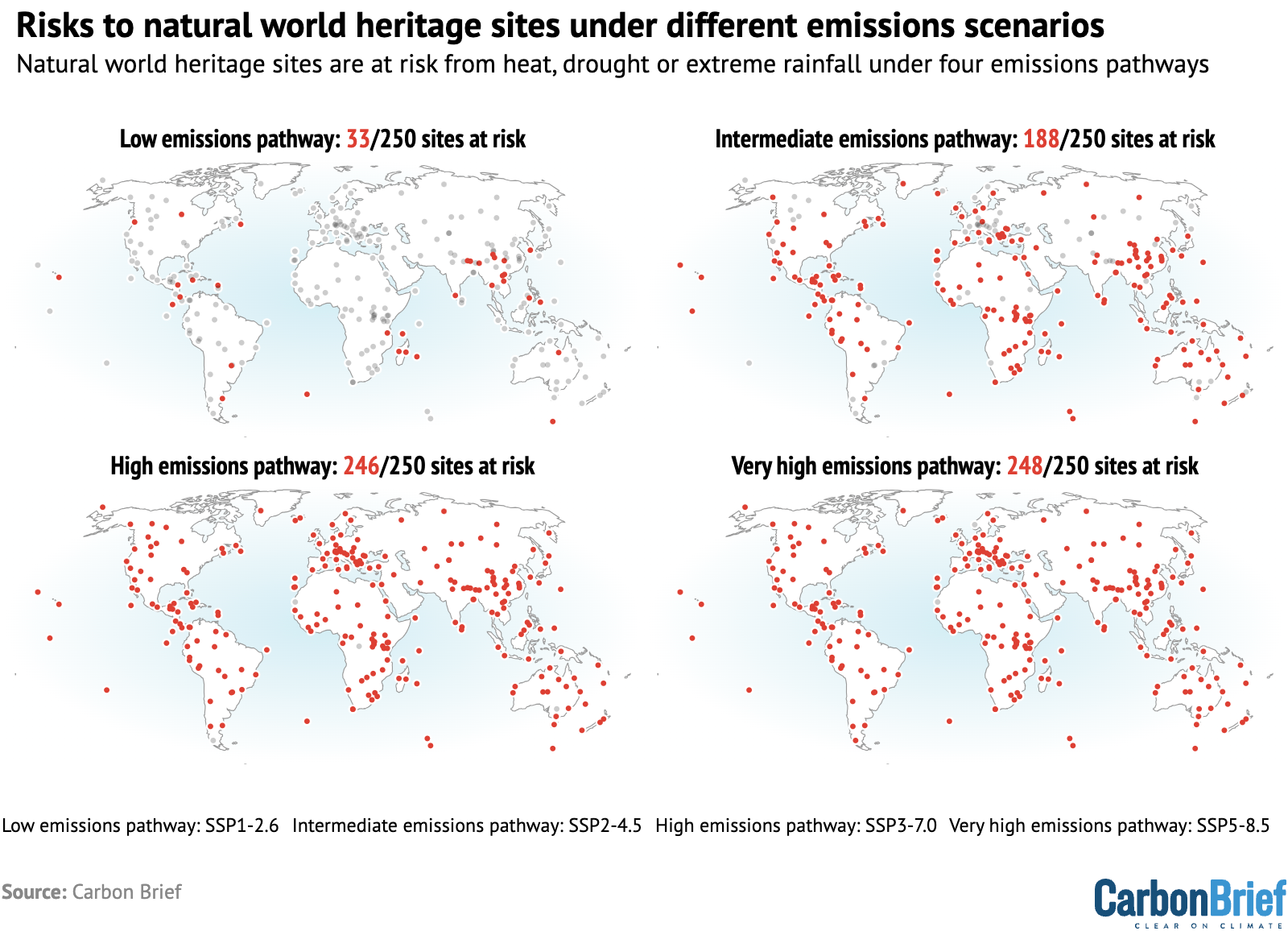

The authors find that, under a low-emissions scenario, 33 of the 250 heritage sites will face at least one “climate pressure” by the end of the century. Under a moderate scenario, this number rises to 188 sites, they find.

Under the highest emissions scenarios, the authors find that nearly all sites will experience extreme heat exposure, with many also facing the compounding impacts of drought or extreme rainfall.

The study warns that sites located at mid-latitudes and in tropical regions, which are often important hotspots for biodiversity, are likely to face the greatest climate risk as the planet warms.

Heat, rain and drought

Recognised internationally as the most important ecosystems on Earth, natural world heritage sites are legally protected under the World Heritage Convention, an international conservation treaty.

But, as the climate warms, natural world heritage sites are facing increasing threats from extreme weather events. In this study, the authors focus on extreme heat, drought and rainfall at 250 of the 266 Unesco natural world heritage sites.

To assess exposure to climate extremes over the coming century, the authors use climate models from the sixth Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6). They use four different Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs), listed below.

- SSP1-2.6: A “low” emissions pathway in which global temperatures stay below 2C warming with implied net-zero emissions in the second half of the century.

- SSP2-4.5”: An “intermediate” emissions pathway roughly in line with the upper end of combined pledges under the Paris Agreement, which results in around 2.7C warming by the end of the 21st century.

- SSP3-7.0: A “high” emissions pathway, which assumes no additional climate policy, with “particularly high non-CO2 emissions, including high aerosols emissions”.

- SSP5-8.5: A “very high” emissions pathway with no additional climate policy.

The Ilulissat Icefjord is an actively calving ice sheet located on the west coast of Greenland, around 250km north of the Arctic Circle. It is one of the few sites where ice from the Greenland ice cap directly enters the sea.

According to the world heritage outlook, “climate change is the greatest current threat” to the site. It adds that “in the next decades there will be higher temperatures both in summer and winter, increased heavy precipitation (>10 mm), and around 2050 the distribution of pack ice will be noticeably decreased”.

The study finds that that site will face “no climate pressure” under the low emissions scenario. However, it will experience “heavy rain” under the intermediate pathway, and will face both heavy rain and extreme heat under the two highest pathways.

Credit: Realimage / Alamy Stock Photo

The Ilulissat Icefjord is an actively calving ice sheet located on the west coast of Greenland, around 250km north of the Arctic Circle. It is one of the few sites where ice from the Greenland ice cap directly enters the sea.

According to the world heritage outlook, “climate change is the greatest current threat” to the site. It adds that “in the next decades there will be higher temperatures both in summer and winter, increased heavy precipitation (>10 mm), and around 2050 the distribution of pack ice will be noticeably decreased”.

The study finds that that site will face “no climate pressure” under the SSP126 scenario. However, it will experience “heavy rain” under SSP245, and will face both heavy rain and extreme heat under SSP370 and SSP585.

Credit: Realimage / Alamy Stock Photo

The authors use the highest daily maximum temperature in a year to measure changes in extreme heat and the annual maximum one-day precipitation to track rainfall. For drought, they use an indicator that calculates the difference between rainfall and evapotranspiration (the transfer of water from the ground into the air through a combination of evaporation and transpiration).

The authors define a site as “being exposed to a climate extreme” when heat, rainfall or drought intensity exceeds a defined threshold by 2100, under any emissions pathways explored.

The researchers established the “threshold value” for extreme heat, precipitation or drought based on the first 10 years of simulated data under SSP2-4.5 – a modest mitigation pathway where emissions remain close to current levels.

Dr Guolong Chen is a researcher at Peking University and lead author on the report. He tells Carbon Brief that the authors chose the intermediate SSP pathway to set the threshold because it “is a more balanced and realistic representation” of the climate than the other pathway. He adds that they decided to take a 10-year average “to reduce the fluctuations in model simulations”.

Mapped

The maps below shows which natural world heritage sites will face climate impacts under different emissions pathways. The dots are coloured red if the site will face climate impacts from heat, drought or extreme rainfall by the year 2100 under low (top left), intermediate (top right), high (bottom left) and very high (bottom right) emissions pathway.

The maps show that under the low emissions pathway, the thresholds for extreme heat, drought or rainfall will only be crossed in 33 of the 150 sites. Many of these are clustered in south-east Asia. The thresholds are not crossed for any of the sites in Europe, the Middle East and North Africa under the low emissions scenario.

However, under the two highest-emissions pathways, almost all of the 250 sites are expected to be threatened by climate extremes.

The authors also find that a significant portion of natural heritage sites are already experiencing extreme heat, posing challenges to conservation.

The study shows that over 2000-15, 45% of sites faced extreme heat, according to the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) ERA5 temperature dataset.

If global warming is kept in line with the low emissions pathway, this number of sites experiencing extreme heat will decrease to 2% by the end of the century, according to the research. However, under all other pathways it would rise, reaching 69% under the intermediate pathway and 98% under the high pathway.

Compound extreme climate events

The study finds that drought and extreme rainfall will be a less widespread threat to natural heritage sites than extreme heat.

The Great Barrier Reef is one of the most famous natural world heritage sites and the largest living structure on earth. The reef attracts two million visitors a year, provides jobs for around 64,000 people and contributes more than $6.4bn each year to the Australian economy

The study finds that the reef will face an increase in the intensity of extreme heat events compared to the expected climate over the coming decade, under all but the study’s lowest emissions pathway.

However, the Great Barrier Reef is already under threat from climate change, as high temperatures cause “coral bleaching”, which can severely damage the reef. Coral bleaching events are becoming more frequent as global temperatures rise, and in 2024, the reef experienced its fifth bleaching in only eight years.

Credit: Ingo Oeland / Alamy Stock Photo

The Great Barrier Reef is one of the most famous natural world heritage sites and the largest living structure on earth. The reef attracts two million visitors a year, provides jobs for around 64,000 people and contributes more than $6.4bn each year to the Australian economy

The study finds that the reef will face an increase in the intensity of extreme heat events compared to the expected climate over the coming decade, under all but the study’s lowest emissions pathway.

However, the Great Barrier Reef is already under threat from climate change, as high temperatures cause “coral bleaching”, which can severely damage the reef. Coral bleaching events are becoming more frequent as global temperatures rise, and in 2024, the reef experienced its fifth bleaching in only eight years.

Credit: Ingo Oeland / Alamy Stock Photo

However, the authors warn that the combined influence of temperature and either rainfall or drought extremes could be severe. The percentage of natural world heritage sites exposed to compound extreme climate events rises from 17% under the intermediate emissions pathway to 31% under the high emissions pathway.

Chen tells Carbon Brief that the study only calculates exposure, and does not “fully consider the varying vulnerability levels across different sites”. As a result, the analysis may not capture the worsening impacts of climate change for sites that are already under threat, he says.

Prof Jim Perry is a professor at the University of Minnesota’s department of fisheries, wildlife and conservation biology, and was not involved in the study. He tells Carbon Brief that this study is the most recent and “comprehensive” review of the impacts of climate change on natural world heritage sites.

Biodiversity threat

Natural world heritage sites make up less than 1% of the Earth’s surface, but are home to more than 20% of mapped global species richness.

As a secondary part of their analysis, the authors focus on threats to biodiversity in the most vulnerable natural world heritage sites.

Brazil’s Pantanal conservation complex area is a cluster of four protected areas, which together make up more than 180,000 hectares of land. The site represents 1.3% of Brazil’s Pantanal region – one of the world’s largest freshwater wetland ecosystems – and is protected due to its extensive biodiversity.

A combination of increasing temperatures, decreased rainfall and other human activity has led to an increasing number of wildfires in the region in recent years. A recent attribution study finds that climate change made the “supercharged” wildfires that blazed across the Pantanal in 2024 around 40% more intense.

The study finds that the Pantanal will face “no climate pressure” under the low emissions pathway, but that under intermediate emissions pathway, heat and drought will both impact the region. Under high and very high pathways, only extreme heat will affect the region, according to the authors.

It adds that “uncontrolled fires could be detrimental for the site’s biodiversity, landscape beauty and wetland ecological functions”.

Credit: Zoonar GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

Brazil’s Pantanal conservation complex area is a cluster of four protected areas, which together make up more than 180,000 hectares of land. The site represents 1.3% of Brazil’s Pantanal region – one of the world’s largest freshwater wetland ecosystems – and is protected due to its extensive biodiversity.

A combination of increasing temperatures, decreased rainfall and other human activity has led to an increasing number of wildfires in the region in recent years. A recent attribution study finds that climate change made the “supercharged” wildfires that blazed across the Pantanal in 2024 around 40% more intense.

The study finds that the Pantanal will face “no climate pressure” under the low emissions pathway, but that under intermediate emissions pathway, heat and drought will both impact the region. Under high and very high pathways, only extreme heat will affect the region, according to the authors.

It adds that “uncontrolled fires could be detrimental for the site’s biodiversity, landscape beauty and wetland ecological functions”.

Credit: Zoonar GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

Chen tells Carbon Brief that the authors chose to focus on forests for this part of the analysis because they are “highly vulnerable to heat, drought and heavy rainfall due to their dependence on water”.

To assess the damage to biodiversity in forested natural world heritage sites to date, the authors use a metric called the “biodiversity intactness index”. This measures the average proportion of natural biodiversity remaining in local ecosystems. The authors class regions with an index of less than 0.7 to be “severely vulnerable”, and those with an index between 0.7 and 0.8 as “vulnerable”.

The authors identify 14 forested natural world heritage sites in the tropics with indices under 0.8 – mainly located in South America, the mainland in Africa, and on various coasts and islands. These include Brazil’s Pantanal conservation complex, Mount Kenya’s national park and Australia’s Ningaloo Coast.

The study finds that the mid-latitudes and tropical regions are likely to face the greatest climate risk as the planet warms. Lead author Chen explains:

“Tropical regions are home to rich biodiversity and diverse ecosystems, including vital natural land types such as forests. There is a more consistent consensus that temperature increases in tropical areas will have a negative impact on biodiversity, threatening the stability of these ecosystems.”

Prof Martin Falk is a professor at the University of South-Eastern Norway who has conducted research on world heritage sites, but was not involved in this study. He tells Carbon Brief that there are challenges to data collection for research on world heritage sites, noting that site managers typically “underreport climate change risks”. He adds:

“Another issue is that the natural world heritage sites in the Western world are over-researched. There is too little on the sites in developing countries.”

-

Mapped: How ‘natural’ world heritage sites are threatened by climate extremes