Roz Pidcock

22.05.2014 | 2:50pmToday’s Mail Online reports on a new study suggesting melting ice sheets could have an upside for Arctic ecosystems, by boosting plant growth.

As a potential way to capture carbon dioxide, the Mail Online’s headline suggests the findings could represent “another positive effect of global warming”. The authors take a more cautious view, however, saying such conclusions are “outside the scope” of the paper.

Unfortunately, it’s seems likely the Mail Online’s headline was inspired by the University of Bristol press release, entitled ‘Iron from melting ice sheets may help buffer global warming’, though the rest of the release doesn’t do much to back up that statement.

The full paper is freely available, so you can have a read for yourself here.

A rush of iron

The Mail Online story stems from research published in Nature Communications. The study looks at the consequences of melting Greenland and Antarctic glaciers for polar ecosystems.

Every year in summer, glacial “outbursts” send thousands of litres of meltwater gushing into the ocean every second. This releases iron previously locked up in the ice, the paper explains.

The Arctic, Southern Ocean and parts of the North Atlantic are low in iron – an essential nutrient for plant growth. The new paper suggests a seasonal iron boost from melting glaciers stimulates plants to grow, drawing more carbon dioxide out of the air.

The scientists estimate the Greenland ice sheet releases 400,000 to 2.5 million tonnes of iron each year. In Antarctica, it’s likely to be less – about 60,000 to 100,000 tonnes, they estimate.

Together, the combined mass of iron is equivalent to about 125 Eiffel Towers or 3,000 Boeing 747s added to the ocean each year, the press release notes.

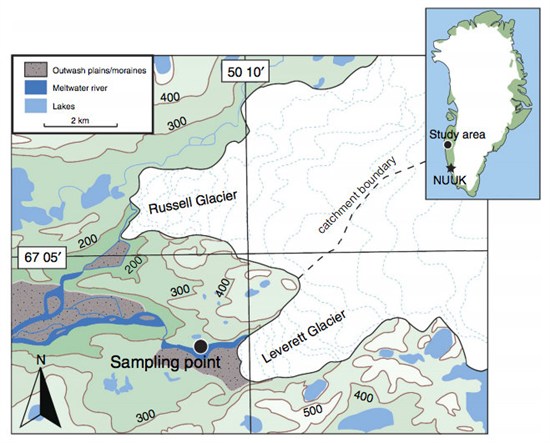

The scientists’ estimates are based on measurements from the Leverett glacier in Southwest Greenland. Since the glacier is representative of more than 75 per cent of the continent, the team scaled their findings up to get an estimate for the whole ice sheet.

Scaling up measurements from the Leverett glacier in Southwest Greenland (pictured), scientists estimate the ice sheet releases 400,000 to 2.5 million tonnes of iron each year, stimulating plant growth in the region. Source: Hawkings et al., ( 2014)

A stretch too far

The Mail Online takes a bold line on the global implications of the new research, saying:

“Huge amounts of dissolved iron currently being released into the oceans from melting ice sheets might cancel out some of the negative effects of global warming, it has been claimed.”

The University of Bristol press release makes a similar connection, though less definitively than the Mail Online. It says the new research “could have a major impact on our understanding of marine food chains and global warming” and that boosting plant growth would “capture carbon – thus buffering the effects of global warming”.

The authors of the paper take a rather more cautious view. While the link between iron and enhanced plant growth is fairly well-understood, it’s not clear how big the effect from glacier melt will be, the paper explains.

Not all the iron unlocked from melting ice makes it to the oceans – perhaps just ten per cent. Iron also exists in different forms, not all of which plants can use. The authors say in the paper:

“The global significance of subglacial iron depends not only on the mass delivered but also on its behaviour following deposition in seawater â?¦ Behaviour is complex … A detailed consideration of these effects is beyond the scope of the present paper”.

Despite claims about global significance, the press release and the Mail Online both feature a quote from lead author Dr Jon Hawkins from Bristol University along these lines. Hawkins says:

“At the moment it is just too early to estimate how much additional iron will be carried down from ice sheets into the sea.”

Another comment in the press release but not in the newspaper comes from Professor Andreas Kappler, who says the study “provides a plausible path for nutrient supply to oceanic life” but adds “the global importance of this flux of iron into oceans needs to be quantified”.

Overstatement

The paper is about glaciers potentially delivering more iron to polar waters in a warming climate, and the boost this could give ocean plant life. But it draws little in the way of conclusions about climate impacts, other than it should be included in global climate models.

A far cry from suggesting melting glaciers could “cancel out” some of the negative effects of global warming, as the Mail Online suggests, this looks like a case of an overenthusiastic press release leading to ill-advised headlines.