Lough Neagh: How climate change intensified toxic algae on the UK’s largest lake

Orla Dwyer

10.19.23Orla Dwyer

19.10.2023 | 3:32pmThe UK’s largest freshwater lake experienced its worst-ever levels of a harmful bacteria this summer.

Lough Neagh – a lake in Northern Ireland that is larger than the country of Malta – has been plagued by blue-green algae that can negatively impact humans, plants and animals.

A group of environmentalists recently held a “wake” to protest the scale of the situation.

Scientists tell Carbon Brief that agricultural nutrient runoff and climate change are the main roots of the problem – and that there is no “silver-bullet” solution.

In this article, Carbon Brief explains what happened on Lough Neagh this summer, how climate change made the situation worse and how it is being tackled without a functioning devolved government in place.

- What happened on Lough Neagh?

- What role does climate change have in the algal blooms?

- What is being done to improve the situation?

What happened on Lough Neagh?

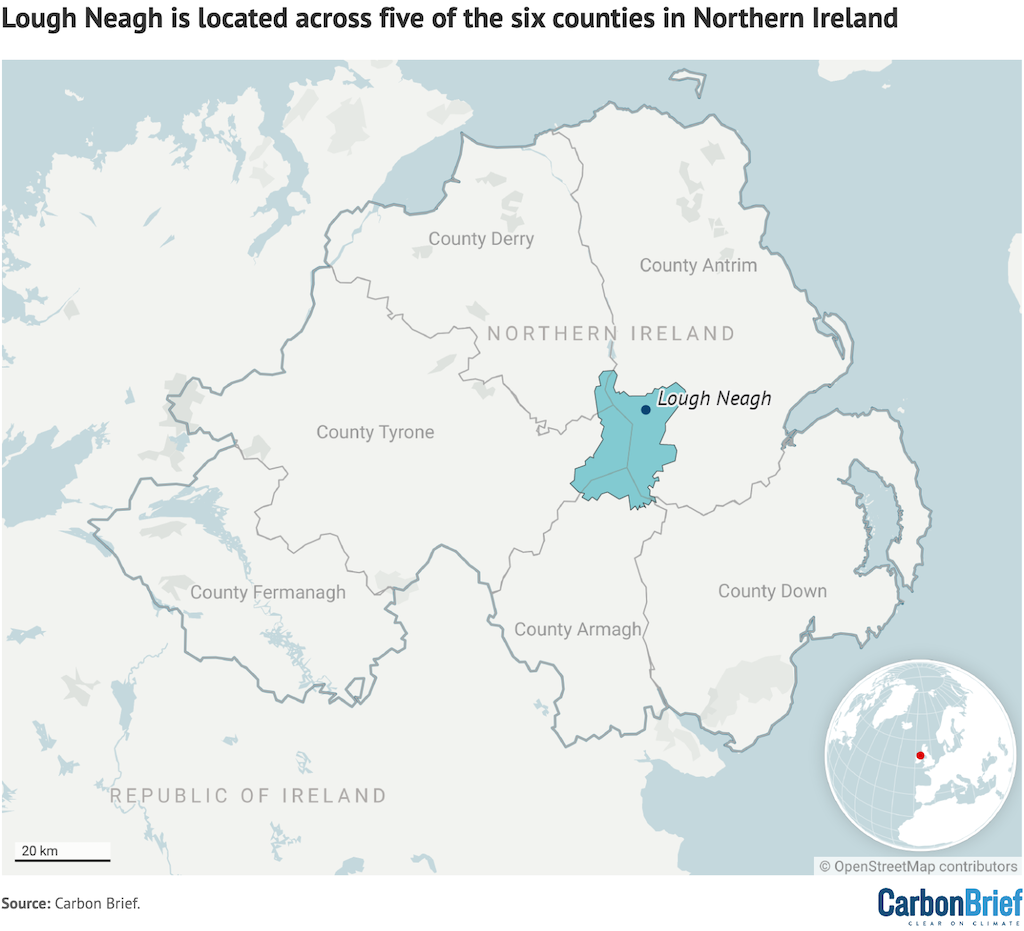

Lough Neagh is the largest freshwater lake in the UK and Ireland, spanning around 380 square kilometres (km2). It holds more than 800bn gallons of water and stretches across five of the six counties in Northern Ireland.

The lake hosts a range of plant and animal species, including whooper swans, tufted ducks and the rare Irish Lady’s Tresses orchid. The wider 5,400km2 basin around the lake holds wildlife-rich wetlands.

The map below shows the scale of Lough Neagh compared to the rest of Northern Ireland.

Since May, high levels of a type of bacteria called blue-green algae have been identified in a number of rivers, lakes and coastlines in Northern Ireland. Lough Neagh has been particularly impacted.

These cyanobacteria – a type of bacteria that can photosynthesise – naturally inhabit freshwater ecosystems.

But if they get plenty of sunlight, CO2 and nutrients – such as nitrogen and phosphorus – they can grow in big numbers and begin to form visible algal “blooms”. The blooms negatively impact the appearance, quality and use of the water.

The recent blooms have affected swimmers and fisheries in Lough Neagh, which contains Europe’s largest commercial wild eel fishery.

It can cause rashes and illnesses in humans and can “potentially kill wild animals, livestock and pets if ingested”, according to the Northern Ireland Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (Daera).

The blooms also block sunlight from reaching other plants and use up oxygen in the water, which can suffocate fish and other creatures.

The image below shows the blooms visible from Copernicus satellite imagery on 4 September. The green swirls of algae are particularly noticeable on the eastern side of the lake.

Lough Neagh supplies around 40% of all drinking water in Northern Ireland. NI Water says that drinking water drawn from the lake remains “safe to drink and use as normal”.

The issue has had a political impact in Northern Ireland, where the devolved government has been at a standstill since last year due to Brexit-related issues.

The climate-sceptic former Northern Ireland environment and agriculture minister, Edwin Poots, said the blooms are a “very significant issue”.

What role does climate change have in the algal blooms?

There are a number of drivers behind the increase in algal blooms on Lough Neagh this summer.

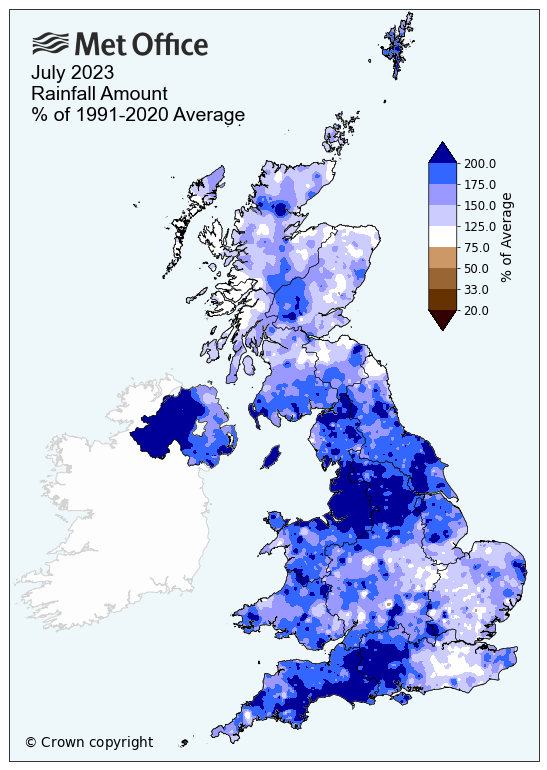

This includes excess nutrient runoff from agricultural and wastewater systems, “combined with climate change and the associated weather patterns, such as the exceptionally warm June, followed by the wet July and August”, Daera says in a statement to Carbon Brief. The department adds:

“This is a complex, multi-factorial issue that will take years, if not decades, to solve.”

Studies say that excessive nutrients are the main cause of blue-green algal blooms in freshwater lakes around the world. Nitrogen and phosphorus occur naturally in water, but agricultural fertilisers, sewage run-off, household products and storm water flows can cause an overabundance of these nutrients

Algal blooms appear as a result of eutrophication – a process arising from too many nutrients in the water boosting the growth of plants and algae.

Lough Neagh is “hypereutrophic”, meaning it is especially rich in nutrients coming from a range of sources.

Prof Mark Emmerson, a professor of biodiversity at Queen’s University Belfast, says the nutrient issue is heightened further by climate change. He tells Carbon Brief:

“We’ve had the wettest July on record. The consequence of that is that when we have farmers who are managing their slurry [mixture of animal waste and water used as fertiliser]…climate events are leading to that being washed out into our river courses and down into the Lough.

“You get this combination of multiple stressors that erode the capacity of an ecosystem like Lough Neagh to absorb and recover from these sorts of events.”

The UK and Ireland have experienced more rainfall on average in recent decades. This trend is predicted to continue as global temperatures rise further, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The map below shows rainfall levels across the UK in July this year compared to the 30-year average. The dark purple areas experienced the highest above-average rainfall levels. Northern Ireland (left) saw more than double its average rainfall for the month.

Rising temperatures also play a role in the growth of blue-green algae, according to Prof Christopher Gobler, endowed chair of coastal ecology and conservation at Stony Brook University in New York. He tells Carbon Brief that the climate impact on blooms is a “no-doubter”:

“If you go back even to the 20th century, the summers just weren’t as warm as they are today. The warming sets up a whole multitude of effects. These blue-green algae, they grow best at really high temperatures. The warmer it gets in general, the better they do.”

A 2011 study found that nutrient levels and climate change “synergistically enhance” cyanobacteria blooms in bodies of water.

However, other research published earlier this year found that nutrients were the main reason behind cyanobacteria growth in lakes in the Americas.

The researchers found “no clear trends” in the links between algal blooms and latitude. Water temperature is “only weakly” related to bloom growth, the study said, saying this aspect has been “overemphasised” previously.

A greater focus on reducing nutrients would improve the situation for lakes such as Lough Neagh, Gobler tells Carbon Brief:

“If you can address the nutrient issue, what that says is that you can actually overcome the temperature issue…In the 20th century, [the] nutrients may have been there, but because the window of opportunity of temperature was short, you didn’t get the blooms.

“But now, since the window is open for most of the summer and the nutrient levels are high – now you’re getting the blooms.”

Other issues have affected this year’s blooms on Lough Neagh. The lake has a high population of zebra mussels, an invasive species, which Daera says upset the “ecological balance” in the Lough.

The filter feeding of the zebra mussels may have contributed to making the water clearer, allowing more sunlight to pass through and boost bloom growth – as well as removing food for native species.

A 2008 study found that harmful blooms in freshwater ecosystems “may lead to mass mortalities of fish and birds” and pose a health threat to cattle, pets and humans. The study, based on modelling, found that high temperatures cause increased growth rates of cyanobacteria and that summer heatwaves “boost the development” of toxic blooms.

The wider impacts on Lough Neagh specifically “remain very much unknown”, Emmerson tells Carbon Brief. He adds:

“We don’t know what the impact on the fish communities that are commercially harvested will have been. We also don’t know what the impacts [are] on the invertebrates that live on the rocks on the bottom of the lake…which are also important food for the fish communities that live there.”

What is being done to improve the situation?

The situation on Lough Neagh is ongoing, but the blooms have started to decline. Daera tells Carbon Brief in a statement:

“Whilst the reporting of visible blooms has decreased and there is evidence that the blue-green algae is starting to break down, the situation of the blooms in Lough Neagh are still being closely monitored, but it is anticipated that as temperatures drop and daylight shortens, the blooms will subside.”

Algal blooms can occur at any time of year and often do on Lough Neagh, but they are most commonly found between May and September.

Daera says it “recognises the seriousness of the situation” this summer and the department continues to assess water quality on the lake.

A team was set up to focus on the immediate response to the situation and a panel of experts will develop recommendations to improve water quality in Northern Ireland, the department says.

Daera adds that any reviews and recommendations for action will be considered in the context of other public-sector demands and also within the “priorities of a returning executive”, referring to the Northern Ireland government which collapsed in May 2022.

The situation on Lough Neagh “vividly illustrates years of political failure – no legislation to protect the environment and no government to address the crisis”, Sky News senior Ireland correspondent David Blevins wrote last month.

The executive has been in a state of collapse for more than 40% of its existence. Northern Ireland’s lawmaking assembly also collapsed in October 2022 over disagreements on post-Brexit trade rules.

Since last year, civil servants have managed government responsibilities. But they are not able to develop new policies or make political decisions, leaving Northern Ireland at a political standstill.

In the past, the UK government has imposed “direct rule” where they took over responsibility for Northern Ireland government decisions during times of collapse. But this has not been implemented since 2007.

The Social Democratic and Labour party last month launched a motion to recall the Northern Ireland assembly to discuss the “ecological crisis” on Lough Neagh, according to BBC News.

Emmerson believes that “nothing is going to happen” in the absence of a functioning devolved government. He tells Carbon Brief:

“I’m confident that we have the technologies, the engineering solutions, the nature-based solutions [and] the capacity to develop social solutions that could work, but whether the political will is there or not, I’m not quite sure – even if we had a functioning government.”

There’s no “silver-bullet” solution to the situation, Emmerson adds, but actions such as planting trees on upland areas to reduce seepage from land to water and reducing fertiliser use on farms would have multiple benefits. He says:

“Many of the solutions which are aimed at improving water quality and addressing the solution in somewhere like Lough Neagh have indirect co-benefits for climate-related action and for nature recovery all at the same time.

“There’s this lack of recognition that the climate and biodiversity and water-quality crises are all interlinked. If you put in place mitigating measures for one, then you are likely to have beneficial effects – what we call co-benefits – for many of the other large-scale crises that we are facing at the moment.”

James Orr, director of Friends of the Earth Northern Ireland, says that although the blooms have receded, the lack of concrete action is “condemning Lough Neagh to more ecological catastrophe in the future”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“That’s the most depressing issue, that we’ve basically condemned these problems to happen repeatedly in the future with much greater severity because they [the government] will do anything other than tackle the sources of pollution – be it human sewage or animal waste.”

Orr says that taking Lough Neagh into public ownership would be one good step to tackle the situation. The bed and soil of Lough Neagh is currently owned by the Earl of Shaftesbury’s estate.

A petition to bring the lough into public ownership and manage it under a single body was submitted to the UK parliament last month. This was rejected.

Nicholas Ashley-Cooper, who currently holds the title of Earl of Shaftesbury, told BBC News that he is willing to sell the lake to the public – “but won’t give it away for free”.

Orr says that if a functioning devolved government had been in place in recent months, there could have been closer scrutiny of politicians, civil servants and the bodies responsible for protecting the environment. But, he adds:

“The system has just got its hands over its ears…[This is] going to happen again and again and again, and it’s going to happen for decades unless we do the obvious thing – reduce the pollution and invest in sewage infrastructure.”

-

Lough Neagh: How climate change intensified toxic algae on the UK’s largest lake