Ros Donald

22.05.2014 | 10:49am cc. Katie Walker

cc. Katie Walker

Using pipes to suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, and storing it underground: doesn’t sound very natural. But what if you were encouraged to think of the process as similar to the role trees perform in nature? A new study finds likening geoengineering to bits of the natural world is more likely to make people feel supportive of technologies that change the climate.

Most people are very attached to nature, and strongly opposed to processes that appear to tamper with it – like so-called geoengineering, which aims to artificially cool the climate. Working from this starting point, a new study from Cardiff University tests whether likening geoengineering to natural processes might reverse some of that negative feeling.

Because geoengineering is a relatively new idea, researchers talking about it have to find ways to explain what it is. Using analogies is one easy way, as Dr Adam Corner, a co-author of the research, says:

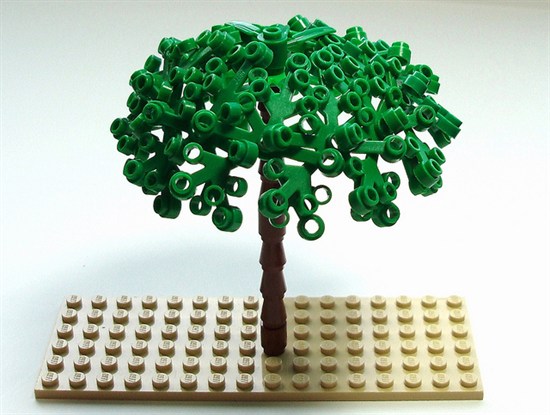

“Scientists and researchers talking about geoengineering are looking for analogies to describe their research. They may describe sucking carbon dioxide out of the air as similar to the workings of an artificial tree, or pumping particles into the air to reflect heat away in terms of how volcanoes work.”

These analogies can be suggested by the way some geoengineering processes are supposed to work, he says:

“Lots of this language makes sense in some ways – for example, the idea of pumping sulphate particles into the air comes from the study of volcanoes, which naturally cool the climate. Our question was that given people care so much about nature – and they see natural things as less of a threat than artificial things – how do these analogies affect our perception of geoengineering?”

Finding ways to talk about geoengineering

Geoengineering technologies broadly take two forms: either they suck carbon dioxide out of the air, or they reflect the sun’s heat away from the earth.

So far, geoengineering technologies haven’t been tested on a large scale, but even with the limited research that has taken place, there are already some high-profile examples of public backlash against geoengineering trials.

That’s perhaps not surprising. Research looking at geoengineering and other nature-modifying technologies such as genetic modification suggests people have a strong instinctive response to them. As the new paper says, people tend to be “fearful of the unintended consequences of climatic intervention and wary of the possibility that the risks of geoengineering will be greater than those of the problem they are designed to solve”.

It adds that while there appears to be limited support for the idea of “careful, incremental and transparent research” into geoengineering, most people are especially concerned about deploying more drastic-seeming technologies.

Putting numbers to the research

To gain a better understanding of people’s feelings about geoengineering and nature, the researchers asked a nationally-representative group of 412 participants to take part in an online survey.

Respondents answered questions about their views on climate change. They also answered whether or not they knew much about geoengineering.

Next, they read factsheets drawn up by the researchers that either likened geoengineering processes to natural ones, like the actions of trees or volcanoes, or used more neutral technical language.

After reading the descriptions, the respondents answered questions about their attitudes to geoengineering, rating each statement from one to five – the mean of these ratings is given on the Y axis on the graph below.

As the graph shows, the researchers found that using the natural analogies gave a small but significant increase in support for geoengineering, especially among those who are less skeptical about climate change. (The left-hand column.)

They were also asked to give some more nuanced views, for example, answering whether geoengineering would help the climate more than hurt it and whether the risks of geoengineering would outweigh the benefits.

They were also asked whether they believed global temperatures were just too complex to be altered by humans, whether they believed geoengineering was natural, and whether it was simply wrong to manipulate nature.

In all cases, the paper suggests that the more people associated geoengineering with natural processes, the more likely it was that people would say they were supportive of geoengineering.

It adds that the results are quite subtle, but that effects outside of the lab may be more dramatic. If people in the real world heard natural analogies to describe geoengineering, they may be significantly more likely to support it.

Corner says:

“This finding is important for geoengineering researchers. If they want to avoid conveying positivity about the technologies they are describing, they should be careful about using natural analogies.”

Other researchers who are investigating how the public understands science and technology say the research is important because it highlights how important language is in debates over powerful technologies.

Dr Rose Cairns at Sussex University says:

“Social and political scientists have long been aware of the power of framing to influence the terms of public discussion. Given the massive potential risks involved with geoengineering, the results of this study underscore the importance for genuine public deliberation, of sustained critical scrutiny of the different ways in which geoengineering is being framed in current debates.”

Dr Jack Stilgoe at University College London adds:

“The paper supports findings from qualitative social research that people’s perceptions of the ‘naturalness’ of technology are important in how they understand massively uncertain, potentially disruptive technologies. I’d be worried if this paper were used by those interested in geoengineering to justify some ‘softer’ geoengineering options over others, or to improve their communications strategies. Social research around geoengineering tells us that lots of non-scientists dislike the very idea of engineering the climate. We need to start listening and responding to that.”

Next steps

So is there any need for further research into communications about geoengineering? Corner says that unless public opinion changes significantly and research into geoengineering is scaled up, priority should be given to research in non-Anglophone, and especially developing, countries. He says:

“Future research should be geared towards understanding how people in other countries understand geoengineering. This would be particularly important in countries where it becomes likely that geoengineering research will take place – which may be developing countries where the public has less of a say in what happens.”